Digit Affair: How Captive Americans Trolled North Korea

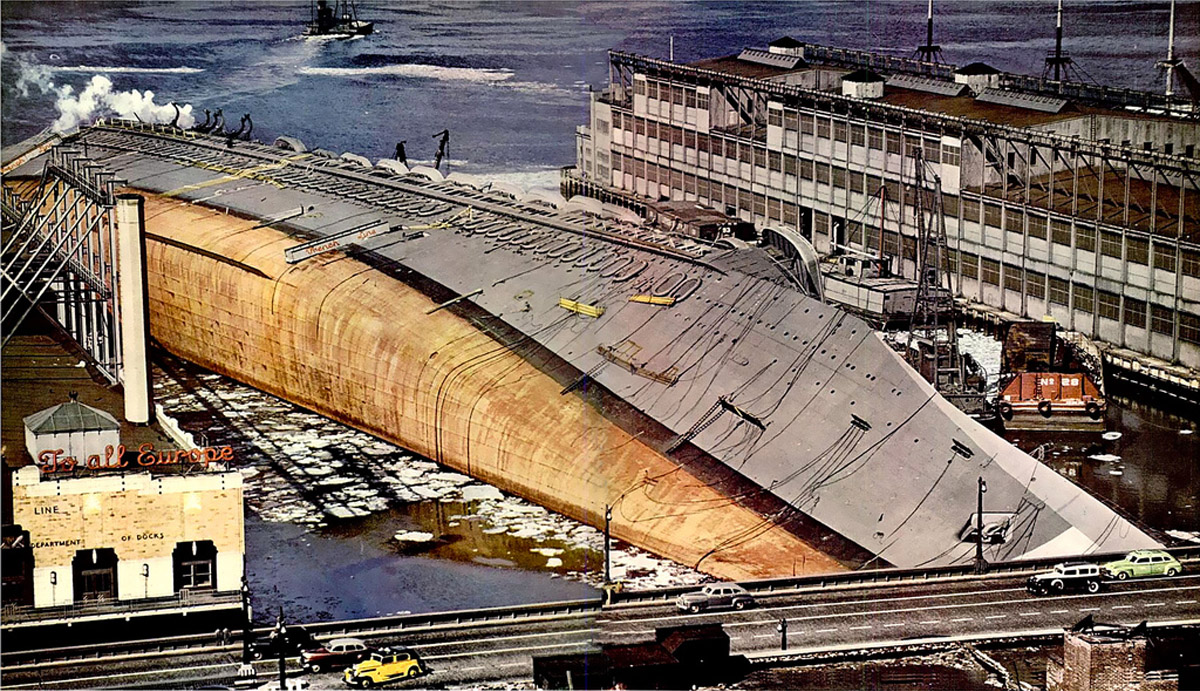

In early November 1967, Pueblo left San Diego port and headed east. A year before that the ship had the name FP-344 and delivered cargo to the US Army units in the Philippines. Now it had a new name that sounded as if it was a civilian ship and was equipped with intelligence radio electronics.

According to the documents, Pueblo was studying marine fauna. The real task was to collect information for the US National Security Agency at the borders of the DPRK.

On January 23, 1967 near the North Korean port of Wonsan the DPRK coast guard cutters caught up with the spy ship. They demanded that the Pueblo reduce speed and report its nationality. The crew of the Pueblo, which was almost unarmed, raised the US flag, but refused to slow down and accept the boarding party, as the ship was in international waters. The Koreans opened fire. One member of the crew was killed, several people were wounded, and about 80 were captured.

Despite calls to immediately launch a military operation, President Lyndon Johnson relied on diplomatic levers. “We shall continue to use every means available to find a prompt and a peaceful solution to the problem,” he said in a TV address several days after the incident. US Ambassador to the USSR asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR to facilitate the release of the crew and return of the vessel.

The American media was creating tension. The New York Times wrote that the incident was humiliating for the US. It came to light that in case it was uncovered, the Pueblo was supposed to receive air support, but it didn’t get any despite numerous calls for help.

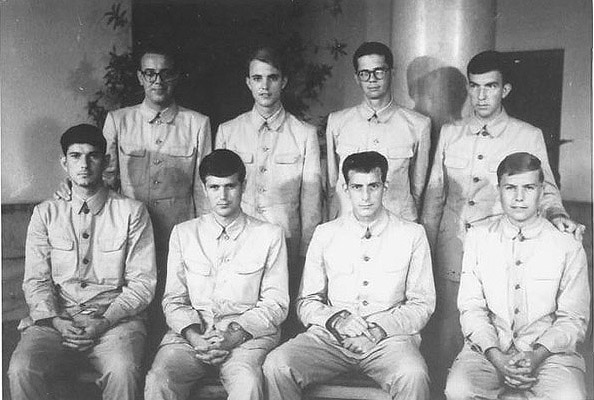

Meanwhile, the crewmen were held in cold cells and regularly beaten. Captain Lloyd Bucher had it harder than the others. His confession of spying was the most valuable, but the Koreans were able to obtain them only by threatening to kill the youngest crew members.

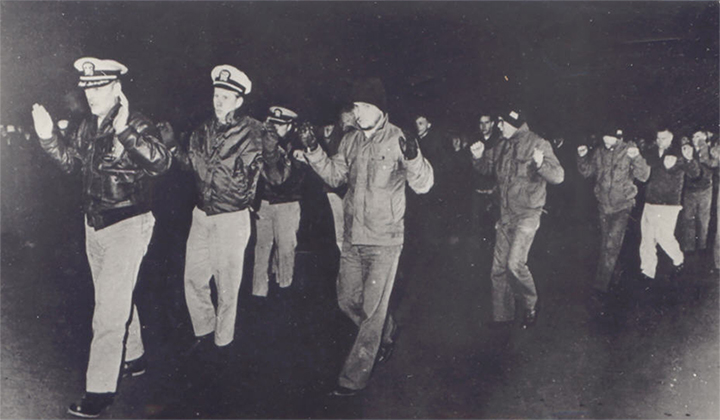

The Americans were used in the propaganda campaign. During the staged press conferences they asked for forgiveness, signed confessions, and sent letters home with the words of support for the DPRK. “Now we have come to realize just how great our crimes were,” captain Bucher wrote. “And we seek the leniency of the Korean people even though we are criminals of the basest variety and deserve only swift punishment of the just Korean law.”

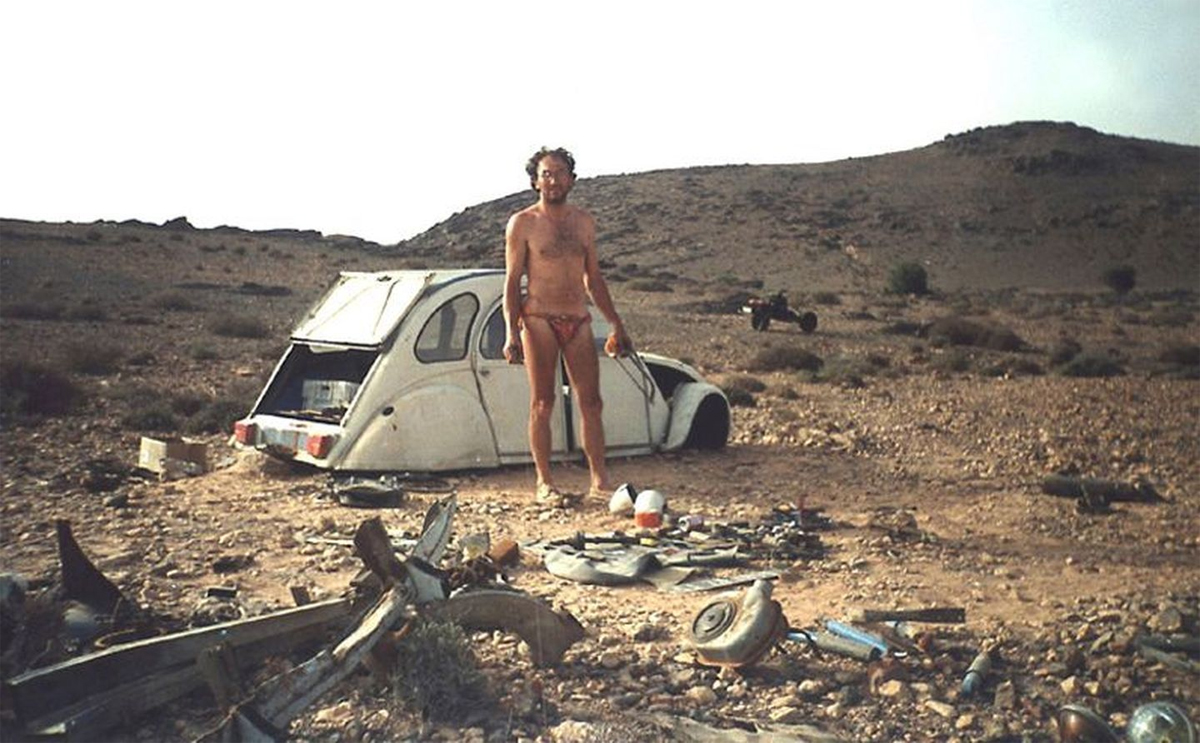

However, the captives were not only characters, but also viewers of the propaganda movies. One night, they were shown several films about the superiority of North Korea over the Western world. The films had footage from the US and Great Britain. Americans noticed that the passersby who were giving a middle finger to the cameraman were not cut out of the film. It became clear that the Koreans were unfamiliar with the gesture. This is how the Digit Affair, as the participants called it, started.

“The finger became an integral part of our anti-propaganda campaign,” Pueblo’s crew member Stu Russell explained later. “Any time a camera appeared, so did the fingers.”

When guards asked questions, the Americans said the gesture was a Hawaiian greeting and good luck. “It could be considered pretty sick humor, but you do what you gotta do. It helped us survive and kept morale up,” Sergeant Bob Chicca said.

Koreans published the propaganda photographs in the American and European media. Most of their readers obviously understood the message that the crewmen wanted to send. However, in the 1968 October issue of Time the photo was captioned with the explanation of the gesture.

Two months after that, the article was featured in the Oriental edition of Time, where the representatives of North Korea saw it. The captives called what followed the week of hell: the beatings were never this cruel. Although the Digit Affair was uncovered, the crewmen did not lose opportunities to laugh at their enemies and prevent their attempts of using them for propaganda. In their letters with apologies, they inserted jokes that the censors could not understand.

“I’ve never met such nice people since our high school class visited St. Elizabeth’s,” one of the Americans wrote, referring to a psych ward in Washington, D.C.

The crew was released on the morning of December 23, 1968 at Panmunjeom border checkpoint, as soon as the American Major General Woodward signed written apologies for an act of spying. As soon as the crewmen crossed the bridge from North to South Korea, Woodward declared he was withdrawing his signature.

New and best