A Facelift Worth Billions: Urbanist on Why Post-war Restoration of Sarajevo Only Made It Worse

The siege of Sarajevo by the Yugoslav People’s Army and the Army of Republika Srpska during the Bosnian War is the most prolonged city blockade in modern history. It lasted almost four years (from 1992 to 1996) and cost the city its historical development and infrastructure. The post-war reconstruction of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s capital did little to improve the situation. Sarajevo city authorities burned through the international organizations’ money, flooding the city with chaotic development.

Dr Haris Piplas — an urbanist and author of the book Non-aligned City: Urban Laboratory of the new Sarajevo — has been trying to rectify the officials’ post-war mistakes and make his native city fit for life again. He told Bird in Flight about the division of the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina into two cities after the war, why Ukrainians shouldn’t expect global architecture celebrities to participate in the reconstruction of Kharkiv, and what Ukrainian architects can do today for their country’s cities to escape Sarajevo’s fate.

We owe this interview to the Restart.Ukraine initiative that aims to reconstruct Ukraine.

.

From your biography, one could say you never settle down. Where have you lived so far?

I was born in Sarajevo, grew up in Berlin, did research in Denmark and Italy for some time, and lived in Milan. Now I reside in Zurich. Living in various cities is a part of an urbanist’s professional development. All urban processes have a physical manifestation and spacial aspect. If you study cities, you absolutely have to live at least in a few. In university, we made a point of visiting 30 cities — from Guangzhou to São Paulo — to get an understanding of their policies, economics, culture, and city structure.

If you had to choose one of these cities to settle in, which one would it be?

I would never trade the experience of living in different cities for settling down. However, I do feel at home in Zurich, Berlin, and Sarajevo.

Both your doctoral thesis and your book are about Sarajevo. In brief, what makes this city so unique?

With its unusual mix of architecture, cuisine, culture, and people, Sarajevo is like a mosaic, which is no wonder, considering that it’s located at the confluence of East and West.

Which major European cities does it resemble?

Architecturally, it’s more like Bratislava because of their common socialist past. In some places, it looks like Turkey’s Bursa or an Austrian town.

A panorama of Sarajevo. Photo: Depositphotos

You were a child when the Balkan War broke out. What do you remember from that time?

A feeling of frustration, helplessness, and anger. I kept asking myself, why does it have to happen in my city? Then, having been around the world, I saw post-socialist East Berlin, post-industrial Detroit, Nicosia, and Belfast. After that, I realized that conflicts and decay could happen anywhere.

What was Sarajevo like before the war?

It was Yugoslavia’s cultural capital. It felt great to live there.

Sarajevo hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics despite having any infrastructure, and then an economic upturn and construction boom followed. The city blossomed and literally exploded in seven years. The country remained non-aligned for a long time, balancing between West and East. It was a blessing until it was a curse. The citizens of the same country suddenly started having territorial disputes, and a war broke out. Looking back, I see how people in the multinational and multicultural city ignored the signs of imminent war. From the look of things, the same happened in Ukraine.

The Siege of Sarajevo continued for over three years. It’s hard to imagine it could last that long. How did people survive?

Keeping yourself warm and fed was the primary concern. To survive, we united and pretended that everyday life continued as usual. We shared food and organized film festivals, exhibitions, and concerts in destroyed buildings.

Sarajevo yards converted to vegetable gardens. Photo: History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sarajevo Olympic Stadium cemetery, 1995. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The festivals in a besieged city, what did they look like?

They took place in bomb shelters. A generator, a projector, and film were enough to hold a festival. Looks like something like that happens in the Kyiv metro.

People risked their lives to go to exhibitions. Still, the war aroused so strong a resistance that people almost stopped fearing it.

It’s my understanding that the sides rarely resorted to artillery and air strikes during the war, so the city sustained only minor damage. Is that true?

Not exactly. Although the shelling primarily targeted the infrastructure, artillery also damaged the city.

Granted, it wasn’t as ruined as Warsaw during World War II, but there was much devastation still. Serbian military made landmark buildings their targets. They damaged the Central Post Office, the TV tower, the Editorial Office, the Islamic Institute, and the Olympic Hall, which accommodated the humanitarian headquarters. They burned the National Library with a million books — it was the most books in human history destroyed at one time, by the way. Greenery suffered even more. About 300,000 trees were destroyed by shelling, fires, and equipment. Besides, locals chopped them down for firewood. In a word, it was urbicide — the physical elimination of city infrastructure and buildings that accentuated Sarajevo’s multiculturalism.

What was the plan for post-war reconstruction, and what objectives did it set?

There was no plan.

What was there, then?

Well, various countries and international organizations donated millions of dollars to reconstruct Sarajevo. The authorities spent the money on repairing the damaged installations, but they did it without any vision for the city.

The latest comprehensive plan for Sarajevo dated back to 1983, and it was a 30-year plan. Nobody bothered to amend it after the war, though.

What was that plan about?

It was a plan typical for socialist countries that envisioned the city as divided into zones: industrial, residential, recreational, etc. It was pretty robust and progressive for its time and involved creating a green frame and multiple green areas for the city.

A new plan had to be developed by 2012, but there has been no progress on that front so far.

If the initial plan was OK, and the city was comfortable to live in before, why just rebuilding it was a bad idea?

As I have already mentioned, the city tripled in size after the Winter Olympics of 1984 and started attracting tourists. Also, it was rapidly industrializing. The plan was based on the assumption that it would remain so. However, the war began, and everything came to a halt. As such, the plan became irrelevant. Besides, nobody bothered to follow the plan after the war.

City authorities developed a guide for investors, indicating on the map the land they could purchase for any purpose. As a result, instead of preserving the industrial past, museums, cultural centres, and offices popped up in the former factory buildings, and many industrial areas were just demolished. The housing built in their place had no infrastructure — there were no schools, kindergartens, hospitals, or anything.

New offices and shops were built where parks and public spaces used to be.

In the central part of the city, Marijin Dvor was short of offices, shops, and premises for the service industry. Where did they build those? In the “free space” where the parks and public spaces used to be. No new parks were created, and the development became denser in the city centre. Traffic jams ensued. Sarajevo is situated in the lowland surrounded by mountains. Rampant high-rise development hampered air circulation, and the air quickly became polluted.

Where were the local architects during all this?

The state architectural offices they worked at before the war closed down. Having lost their jobs, local architects were not prepared for the new reality and had no influence on what happened to the city.

Local architects were not prepared for the new reality and had no influence on what happened to the city.

Why not invite a big-name architect, like the Kharkiv authorities did when they commissioned the city master plan to Norman Foster?

For starters, I don’t think anybody should be entrusted with developing a city plan single-handedly. Nobody has this kind of experience. Numerous architects are willing to help rebuild Ukrainian cities. However, I doubt that most of them can even fathom how difficult it is. One person will sure do a poor job of it.

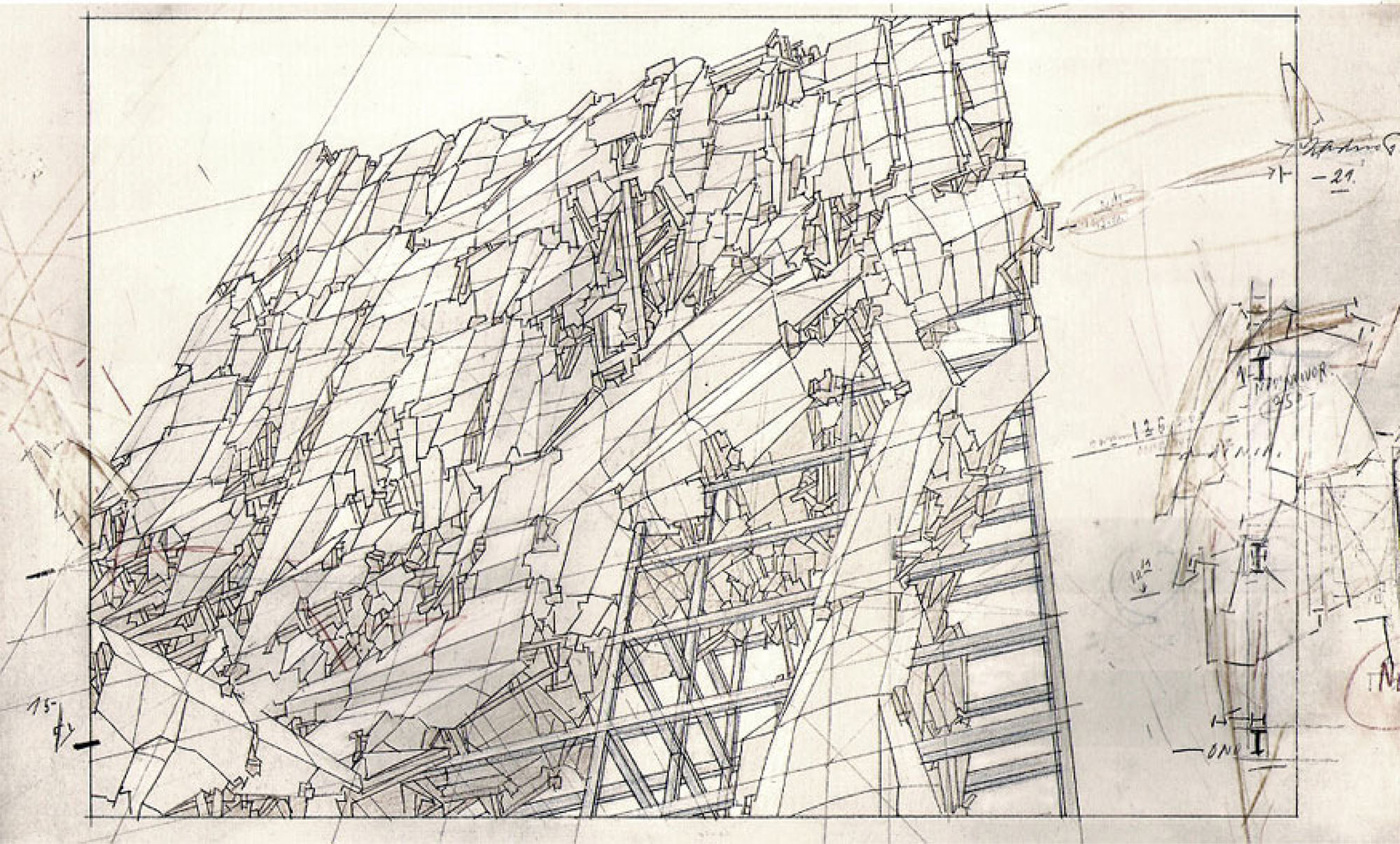

Then, Sarajevo authorities did invite Lebbeus Woods and Renzo Piano. It didn’t help. The former came up with the architectural development concept, and the latter offered to build a contemporary art museum. Both ideas remained on paper, though. Why? Because you have to set appropriate goals for the star professionals you invite.

Lebbeus Woods’ parliament building reconstruction concept. Photo: Lebbeus Woods. War and Architecture / Princeton Architectural Press

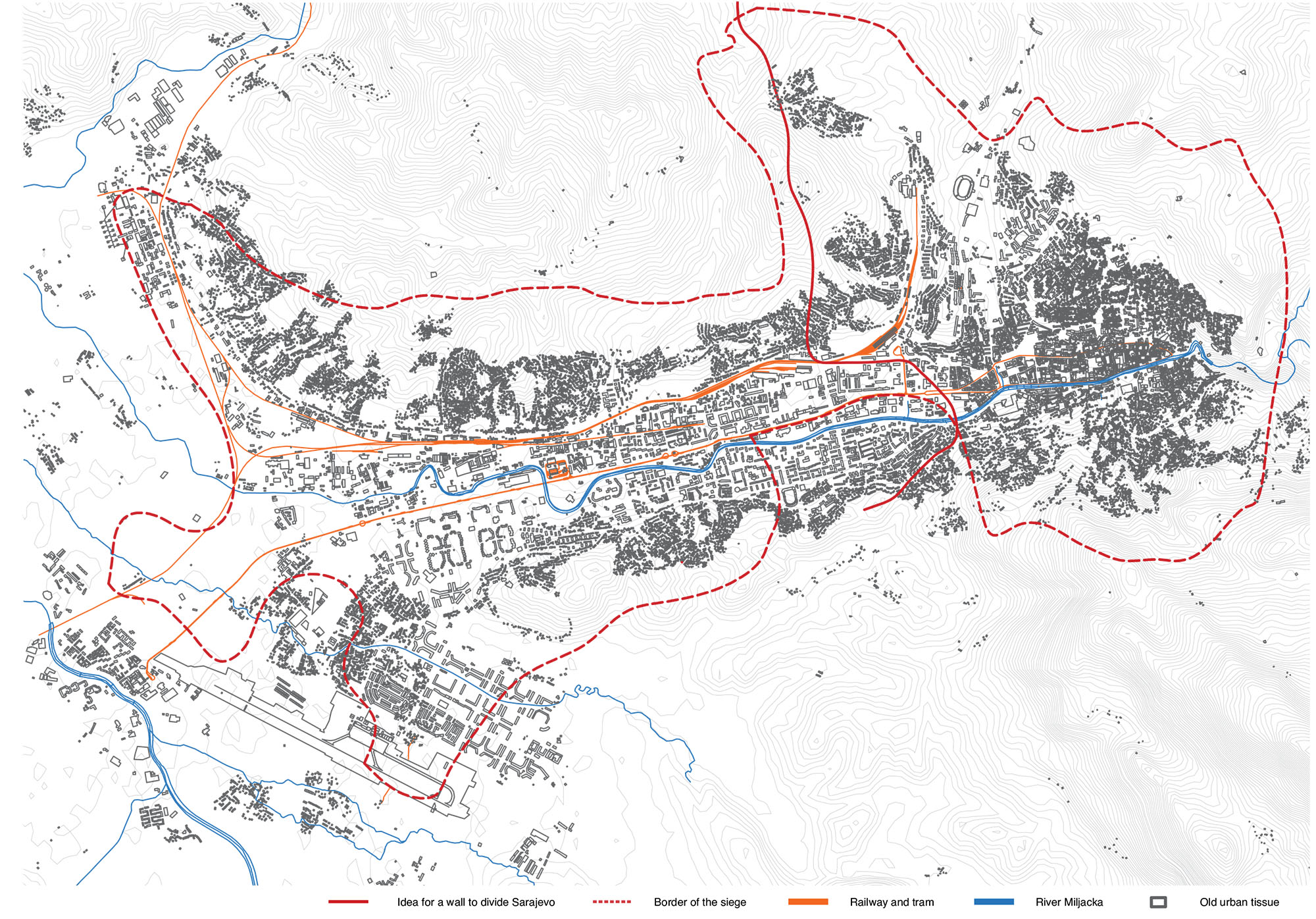

It’s common knowledge that Berlin was split in two by the wall, but few are aware that a similar thing happened to Sarajevo. Why was the city divided?

It wasn’t the city alone. The peace treaty divided Bosnia and Herzegovina into two administrative entities: Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. And the border between them divided the city into Sarajevo and Istočno Sarajevo (East Sarajevo). The parallel to Berlin that you have drawn is not entirely accurate. The German capital was split in half, while Istočno Sarajevo is just a suburb. Also, the border is conventional. There is no physical wall there, even though some people wanted to build it. When you cross from one side to the other, you notice that signs are written not in Latin but in Cyrillic script, and Orthodox churches appear instead of mosques. Historical landmarks are another indicator of where you are. In Istočno Sarajevo, you see monuments to Gavrilo Princip and former Ambassador of Russia to the United Nations Vitaliy Churkin, who notoriously denied the Srebrenica genocide.

Has this divide been overcome?

No. While Istočno Sarajevo is still a monoethnic locality, Sarajevo residents have been frequenting it lately, going to cafés and even buying flats there.

Sarajevo map. Drawn in red is the siege line — it later became the border between Sarajevo and Istočno Sarajevo. Image: Haris Piplas

So, the reconstruction turned Sarajevo into a fragmented, mindlessly developed city, which is difficult to live in. Have I got it right?

Sadly, yes. Basically, it’s my job to make sure it ceases being that.

What do you do for it?

I study the city, draw conclusions, recommend appropriate solutions, and look for partners to implement the changes. I also initiated the Reactivate Sarajevo Urban Transformation platform. But it’s a long process. It’s hard to even study Sarajevo because many archives were destroyed during the war.

Besides, there were no tools for architect and urbanist work in Sarajevo back when I began: no rules, architectural contests, or a general plan. Now we develop them. We involve various universities and organize platforms and educational events.

For 25 years, Sarajevo existed without any development concept, so we strive to create it.

What is your end goal?

The post-reconstruction of the city.

How many years of your life have you devoted to this?

Fifteen. I started back when I was a student.

Do city authorities help?

Formally, we are on good terms with each other, but it was I who approached them with an offer to restore the city, not the other way around. Anyway, I’m optimistic, although there’s always a chance that the new concept doesn’t work out or there is insufficient coordination to implement it.

Have your work yielded any results?

As a part of my platform we have helped the young generation to get their education and experience abroad. I managed to get these people interested in urbanism, and now they want to change Sarajevo. Besides, we have started developing new urban strategies and laws on the city council level jointly with Zurich City Hall. I’m proud of these achievements of mine.

What Sarajevo do you dream about?

A united city, in which the residents co-operate with each other and there are lots of public spaces, community buildings, cultural venues, and greenery.

However, I have no influence on the plan, and I can’t predict how and when it will be implemented — it’s the responsibility of city authorities.

Finally, our traditional question: what is your advice for the architects and urbanists who will tackle the post-war restoration of Ukrainian cities?

First, you need to coordinate and create a unified vision of the future and the tools to build it because the energy bubbling in Ukrainian architects’ heads can be used inefficiently. If it happens, you would see the post-war reconstruction of your country as a wasted opportunity 20–30 years down the road.

You would see the post-war reconstruction of your country as a wasted opportunity 20–30 years down the road.

The post-war Sarajevo authorities made a mistake when they didn’t coordinate with the international organizations willing to help the city. Hopefully, Ukrainian cities will pay more attention to this. No change can happen if it’s fragmented. Therefore, your first step should be establishing a platform to coordinate all initiatives.

Second, I suggest you stop thinking that international partners will rebuild your cities by themselves. It’s Ukrainians who should decide what their cities would look like. You have been scattered all over the world now, and you are seeing new things. This experience must be leveraged during reconstruction.

Third, pay attention not only to the economy but to ecology, culture, and infrastructure.

The cover picture collage is based on the photo by GEORGES GOBET/AFP, Depositphotos

New and best