Dead and Combat Dolphins: How War Affects Black Sea Animals

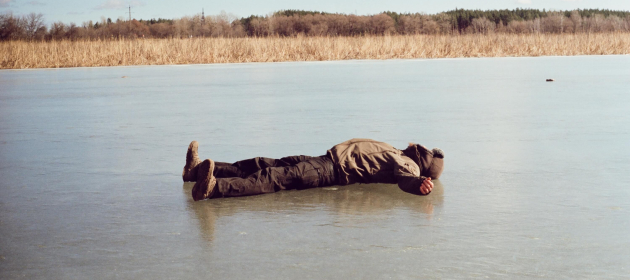

At the autopsy, there are two investigators from the Security Service of Ukraine and the prosecutor’s office, three representatives from the State Ecological Inspection, two experts, and a veterinary forensic expert. All this attention is focused on the body of a porpoise found on one of the beaches in Zatoka, Odessa region. How long it had been on the shore is unknown, but it had been lying in the cold for 16 hours before the autopsy and didn’t completely thaw, making the examination difficult. Moreover, the table with the body in a black bag is placed outside, in the yard of the Hydrometeorological Center of the Black and Azov Seas in Odessa. Thunder rumbles in the sky, scientists are trying to complete the research before the rain.

Of course, everyone is interested in the cause of death. It could be an infection, illness, or something else, including specific actions by Russian occupiers—both in the water and on land. During the autopsy, samples of tissues and organs are collected: brain, ears, liver, lungs, heart, and so on. They will be sent for examination to conduct histological, toxicological, and other tests. The instruments are in the hands of Karina Vyshnyakova, a scientific researcher at the Ukrainian Scientific Center for Marine Ecology. The procedure is supervised by Pavlo Goldin, a senior researcher at the I. I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology.

Before the specialists lies the carcass of an adult marine mammal, a Black Sea porpoise, or simply a marine pig. These are a type of cetacean that lives in the Black and Azov Seas. The rainstorm is starting – the porpoise’s blood is mixing with raindrops. Due to the bad weather, the autopsy is suspended, so the procedure extends to almost four hours. Afterward, the body will be buried in the yard, and the bones will be used for research in the future.

In truth, law enforcement officers are not often involved in such operations; they are here precisely because of the possibility that the animal died due to Russian aggression. Recording such cases allows for a complete picture of crimes and can later be used in court. Ukraine intends to hold Russia accountable for ecocide, the destruction of animal and plant life on its territory, and is collecting evidence for this. Before the anniversary of the full-scale invasion, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine reported about a thousand documented cases of dolphin deaths on the coasts of Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Turkey. Ivan Rusiev, the head of the scientific department of the National Natural Park “Tuzlovski Limans,” a doctor of biological sciences, estimates the number at 50,000 dolphins that died within the year of the invasion. He assumes that the sea or ocean usually washes up only 5% of dead animals, so we are not even aware of most of the victims.

Law enforcement officers are not often present during such operations; they are here due to the possibility that the animal died as a result of Russian aggression.

The process of dissecting the Black Sea harbor porpoise

However, Pavlo Goldin is skeptical about any assessments. According to him, it is currently impossible to determine even the probable number of deaths and injuries among marine mammals due to Russian aggression. Scientists are constantly collecting information and, like today, examining the bodies of the deceased, sending samples for analysis to colleagues from Ukrainian and European universities, but the results will not be available soon.

Three species of cetaceans inhabit the Black Sea: beaked whales, bottlenose dolphins, and common porpoises. All of them are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine. And because these are endangered species, a special permit from the Ministry of Environment is required for each dissection. But this is not the only thing slowing down the process.

“For example, on Friday, border guards found a dead dolphin on Rosytsya, but the area is so dangerous that they couldn’t even access the beach themselves. There are only surveillance camera photos; the body cannot be retrieved,” Pavlo Goldin explains. “On Thursday, a dolphin was washed ashore at the ‘Dolphin’ beach. We took it – used the director’s car and brought it ourselves.”

Border guards found a dead dolphin on Rosytsya, but the area was so dangerous that they couldn’t access this beach.

Despite all the uncertainties, it can be stated with certainty that armed conflicts generally have a negative impact on marine mammals. Pollution of the water, infections, and the operation of sonars from submarines – all of these factors contribute. Due to sonars, dolphins can lose their ability to navigate and hunt properly, affecting their ability to feed.

“In the sea, missiles often explode, which can be a source of blast injuries for animals. And this is just one of the many possible risks,” adds Goldin. “For example, after the explosion of the Kakhovka Dam by the Russians, a lot of various pollutants entered the sea – heavy metals, pesticides, and organic substances that alter the biochemical balance of the sea. All of this can affect the population of fish and dolphins that feed on them. In the Black Sea, cetaceans are a key species, meaning their impact on the ecosystem is much more significant than it might seem. Their reduction or demise could change the entire Black Sea ecosystem.”

In the Black Sea, cetaceans are a key species, meaning their impact on the ecosystem is much more significant than it might seem.

Obviously, the sooner the military actions cease and Ukraine regains its territories, the sooner it can truly assess the scale of the tragedy, and nature can finally begin to heal.

Combat dolphins

In addition to indirectly impacting marine mammals, Russian military forces appear to directly exploit Black Sea dolphins. British intelligence reported on combat dolphins allegedly used by Russia to protect the Sevastopol Bay. Through satellite imagery, the UK Ministry of Defence discovered that Russians had deployed trained marine mammals as barriers for guarding the Black Sea Fleet base.

Scientific researcher at the I.I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, Pavlo Goldin

In general, the idea of using marine animals for military tasks was attempted during World War I. At that time, seals were trained by the Russian Imperial Navy to search for mines. However, these training efforts did not progress further.

In 1965, a special experimental base, which later became the research center “State Oceanarium,” was established in Sevastopol. Initially, dolphins were used as models, studying them and applying the obtained data in shipbuilding and marine weaponry. In March 1973, the navy leadership received a classified report from the US Naval Military Center in San Diego, learning that Americans were training dolphins and killer whales to search for and retrieve sunken torpedoes. Similar experiments were conducted in Sevastopol – dolphins were mostly used for searching and retrieving specific objects.

There are also reports suggesting that dolphins were trained to attack humans in case of infiltrations by saboteurs onto the base. Special devices with high-pressure air were attached to the dolphins, which were supposed to use these devices to strike enemies. However, there is no evidence that this method was effective. Additionally, according to some information, animals could be taught to attack ships by attaching explosives to them, but details about such operations remain unknown. In any case, the animals themselves suffered the most – they were captured, forced to live in captivity, and subjected to experiments.

There are also reports suggesting that dolphins were trained to attack humans in case of infiltrations by saboteurs onto the base.

Researcher Karina Vyshnyakova from the Ukrainian Scientific Center for Marine Ecology

In 1992, the “Oceanarium” came under Ukrainian control. Military experiments with marine animals were halted and partially resumed only in 2012, allegedly for search missions using dolphins. However, in 2014, the Russians captured the “State Oceanarium” and, according to British intelligence reports, continued training the animals.

By 2022, satellite images revealed that the Russians had placed dolphin enclosures at the entrance to Sevastopol Bay, purportedly for patrol or protection against potential saboteurs or drones. Initially, according to British intelligence estimates, there were only three to four dolphins. Recent photos showed that the number of enclosures increased to six or seven. Of course, in the modern world, it is more effective to use technology for various tasks at sea. However, if the Russians lack such technologies, it is likely that they will still rely on dolphins for specific missions.

“Military dolphins are about as effective as using a combat elephant nowadays,” said Pavlo Goldin. “It’s absurd that the Russians have started tormenting animals again, reminiscent of Soviet times. But if that’s how they treat people, there’s nothing surprising about it.”

Photo: Yana Kononova, specially for Bird in Flight

This material was created as part of the “Life in War” project with the support of the NGO “Laboratory of Public Interest Journalism” and the Documenting Ukraine project at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. (Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen, IWM).

The material was also released with the support of the Emergency Support Initiative by Kyiv Biennial.

New and best