I Survived, Here’s the Evidence: Photos of the International Legion Fighters

Was born in the city of Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1989. Worked as a ski instructor and founded the tourist company Snow Vigil in Georgia. Served in the Ukrainian International Legion.

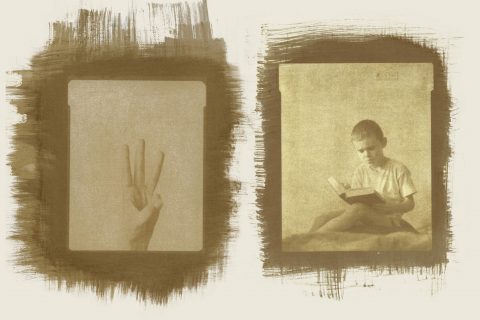

— My interest in photography started when I found my mother’s old Pentax camera. I got a couple more 35mm cameras from thrift stores later on, and I took photos constantly. At school, wandering around my neighborhood. Most of my photos were very unassuming portraits of my classmates.

I always dreamed of leaving the US. I was enticed by the feeling of venturing beyond the known and familiar. I became fed up with my life as a graduate student at University of Wyoming and went on a tour overseas.

Ukraine was my main interest. After watching the Revolution of Dignity closely, I came to Ukraine in 2016-2017 and made many friends, most of whom were Maidan activists.

From 2020, I worked as a ski instructor in Georgia, where I opened my own company organizing winter tours. The job was risky, but I could never have imagined how dangerous the next one would be: I became an infantry sniper in the International Legion. The full-scale invasion caught me in Georgia, but I didn’t hesitate for long – I bought tickets to Ukraine the same day. I have many friends here, and I couldn’t just stand aside while they were in trouble. Specific people I love motivated me to get up and help.

Perhaps I could have been more helpful in some other way; after all, I never served in the army. But when the house is on fire, you grab buckets and run. If I’m here, I’ll help in the most extreme but best way possible. While I was traveling to Ukraine (it took three days), the International Legion was formed.

My parents gave me my first rifle at the age of 10, and since then, I spent every weekend in the forest shooting. I think I was pretty good at it; I often participated in competitions. Although I had no combat experience – I never supported the wars of the USA – I was always interested in sniping. I gave up this hobby only a decade ago and almost forgot that I knew how to do it. Then, in the Legion, I taught others how to shoot.

My parents gave me my first rifle at the age of 10.

Training at the shooting range with a captured machine gun "Kord".

My comrade in a camouflage suit sits opposite Ukrainian soldiers on an armored vehicle.

One of the comrades jumps out of the sprinter van.

Rest between training sessions at the shooting range.

My family has come to terms with the fact that my job is dangerous. My parents know I am in Ukraine and support me, but we decided to keep it a secret from my grandmother. She still doesn’t know that I am at war.

Right now, everything in the Legion is organized, but in the first days, no one understood what to do or how to do it; there were no training sessions for the fighters. But it was understandable: Ukrainians had to create a new military formation with a bunch of foreigners from scratch in the midst of the war. Even the French Foreign Legion wasn’t created under such circumstances.

In the International Legion, I met many people who felt they hadn’t done anything valuable in life, so they wanted to finally make a difference. They told me this directly. There were also those who were just bored and looking for adventure, and many former American military personnel. I think after Iraq and Afghanistan, many of them came to Ukraine because they felt they had been involved in unjust wars. Here, they can finally do what they do best but for a good cause.

I personally believe that all wars were horribly wrong. Yes, Americans also committed war crimes against civilians. Even those who supported the war in 2003 now admit they were wrong. But no one today will say that it was justified.

Anti-tank missile system "Fagot," from which the Russians were planning to attack us. In the background, you can see a dead Russian soldier – the result of Ukrainian artillery work. We are reclaiming positions lost to the enemy.

My comrade Olav is passing a cigarette to another, Austin. We stopped in front of a ruined building on the way to the base to admire the sunset.

Weekend. Found ourselves a pastime: going into an abandoned building, having a beer on the balcony - it's allowed on Sundays.

I convinced the guys to go for a picnic by the lake. We ate a bit and found a frozen swamp. Played on the ice, maybe not the safest activity.

My comrade in a trophy beret of the Russian Federation Airborne Troops (VDV).

In their free time, people in the legion usually just play video games, even shooters. I had a different hobby – I started taking photos. I saw some projects by foreigners about Ukraine, but none of them appealed to me: from the photos, it was clear that the authors already had an impression of the country and came here to confirm it. So, they shot gloomy landscapes with panel buildings. Such series were vulgar and uninteresting. That’s probably why I wanted to create my own.

When you’re a photojournalist, for the military, you’re an alien. But for me, their comrade, it’s an entirely different perspective, I’m on the inside. I believe that even those who have “zero access” don’t see the war through the eyes of the military. At the same time, I’m a foreigner. When I lived in Ukraine, I always felt a bit outside of everything that was happening. So, perhaps, while I might understand people better now, I’ll probably always be like those photographers who come to shoot soldiers.

I never had experience documenting a war; I just use common sense. Journalists have rules for controlling the quality of their work, and I set my own rules. I understand that if I do something foolish and publish something I shouldn’t, like images of the places where we live or fight, we could die. Besides, in the first months, even in Kyiv, people with cameras were viewed suspiciously; you couldn’t take photos on the streets. I also would never photograph fallen Ukrainian soldiers out of respect for them.

My comrade is getting ready to climb onto the armored personnel carrier.

Fog during the last days of the counteroffensive in Kharkiv region. Getting ready to move to the next village.

The end of the counteroffensive coincided with the end of autumn with its fogs and mud..

Lunch in the forest before the advance in the east of Kharkiv region.

Some moments are so overwhelming that I forget I’m on the battlefield and look at things as a photographer. I had a shot where soldiers were playing “Monopoly” in a basement during shelling. When you encounter something as mundane as a board game or as beautiful as a sunset in the midst of war, it takes your breath away with emotions. You realize that despite the war, life goes on. The sun rises and sets, flowers bloom, and people remain human even in the harshest circumstances.

I chose analog photography by accident – my two best cameras were stolen and destroyed. But because of that, I started to value my work more. I try to protect my camera and film, knowing there is no backup copy. Every time I manage to shoot a roll without damaging or wetting it, it’s a small victory, very similar to surviving a mission. The photographs are proof that both the camera and the photographer survived.

The photographs are proof that both the camera and the photographer survived.

I wanted to capture more of the locals living in the conflict zone. Ukrainians seem to adapt to any circumstances, such as working in fields under shelling, and it still amazes me.

I remember how surreal it was to approach the positions of the Russians on the front line, where they had been living for many months. It felt like stepping into a completely different informational world. Books about the “Great Patriotic War,” propaganda literature, personal belongings left behind — they believed in something entirely different, and it was very strange. I photographed it, but the pictures didn’t survive; they were on destroyed film.

In the legion, we spent eight months retaking and then holding a village in Donbas, which I can’t name now because it’s still a hot spot on the front line. Months passed advancing only on one street. However, I felt that I was defending what I believed in. But my biggest achievement in this war, I consider the ability to leave when I realized I had given enough. People think that if you have the opportunity to leave the military, you will eagerly take it, but it was hard.

I visited my family in the USA because I hadn’t seen them in four years. Now I work as a volunteer, for example, I brought sights from the States. I don’t know what will happen next, but I plan to connect my future with Ukraine and even want to eventually obtain citizenship.

New and best