Shrapnel Wound: Eight Years of War in Dmytro Kupriyan’s Photos

A Ukrainian documentary photographer, he used to work for UNIAN and other Ukrainian mass media. Now his focus lies on personal projects. His works were exhibited in Ukraine, Georgia, Italy, and Hungary.

— I went to the recruiting station at 7 AM on the 24th of February. Now I’m with the army, and it’s my primary occupation. However, I keep working on one of my longest-running projects — Fragments of War.

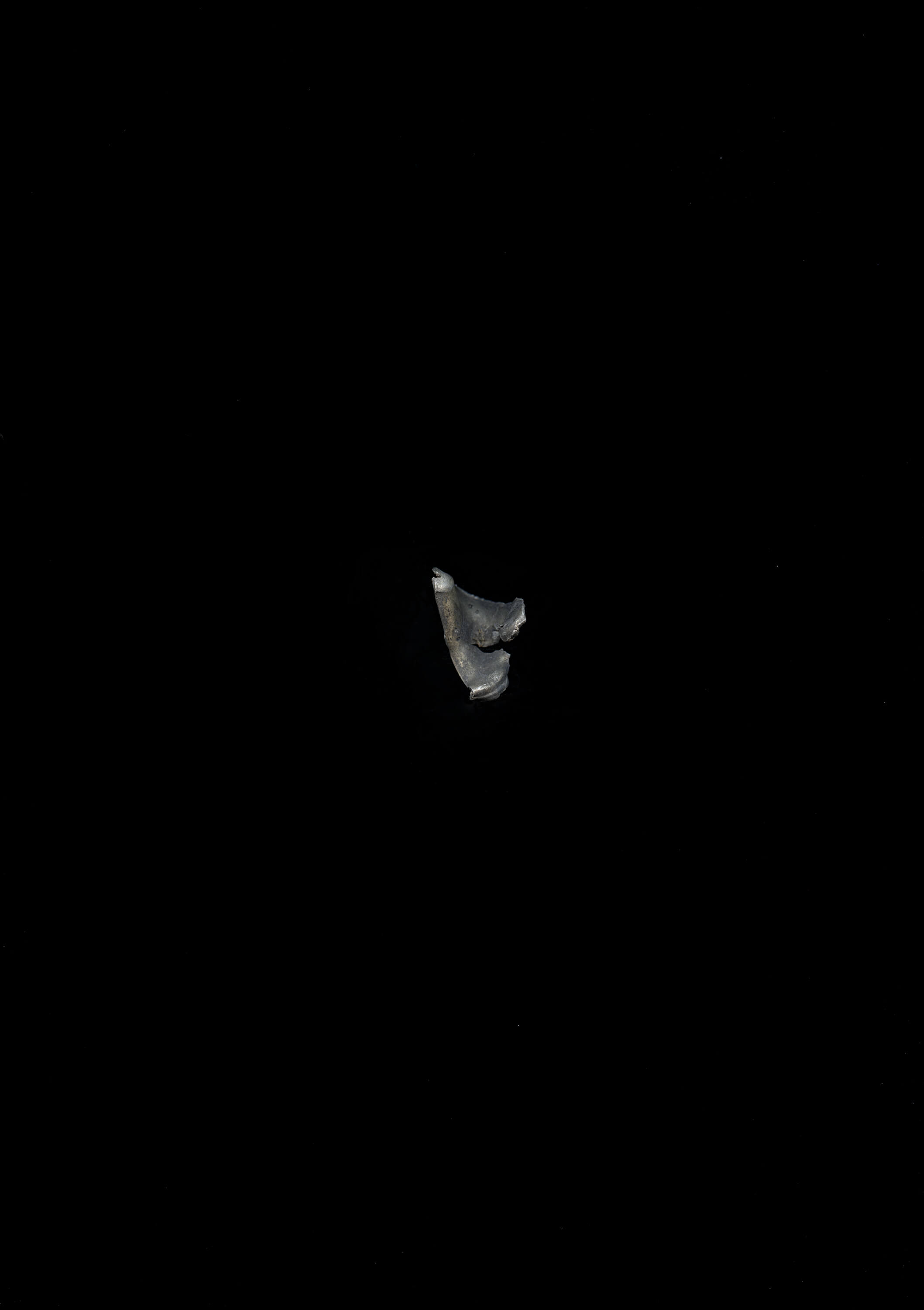

I’ve accumulated lots of photos over the time Ukraine has been at war. However, they lacked a unifying trait until I remembered the shell fragments I had brought from the frontline. I’ve been collecting them since 2014. I found munition fragments in Pisky, Stanytsia Luhanska, Debaltseve, Shchastia, and other places in Donbas that made the news. Those fragments reminded me of asteroids with sharp edges that could kill everything in their path.

Every fragment — I have eleven of those — has a story connected to the circumstances under which I found it. Sadly, we will never know for sure what side they came from. I always add that it’s likely to be this or that kind of munitions because sometimes it’s hard to tell if it actually is.

They all comprise a continuous story about the war and the destinies of soldiers, volunteers, and civilians. I feel that many people have become just like these fragments because of the Russian aggression, torn from their regular lives and ending up on the battlefield.

Many people have become just like those fragments because of the Russian aggression, torn from their regular lives and ending up on the battlefield.

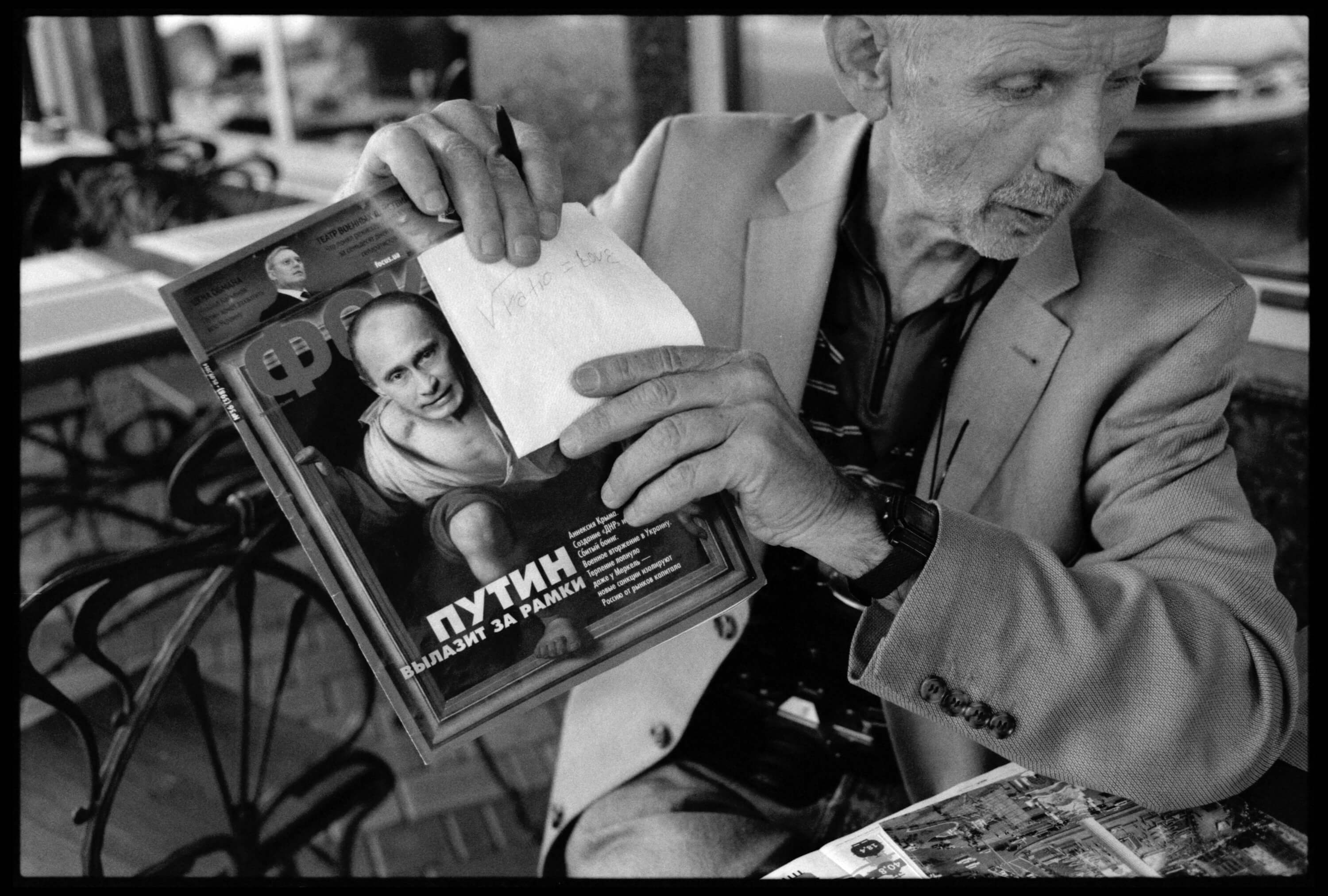

The 2017 trip to Sloviansk was the most memorable for me. People had already returned to their usual lives there, but it felt weird that locals didn’t speak a word about the war. After all, the city was in occupation mere three years ago. Everybody pretended that nothing was going on and never had.

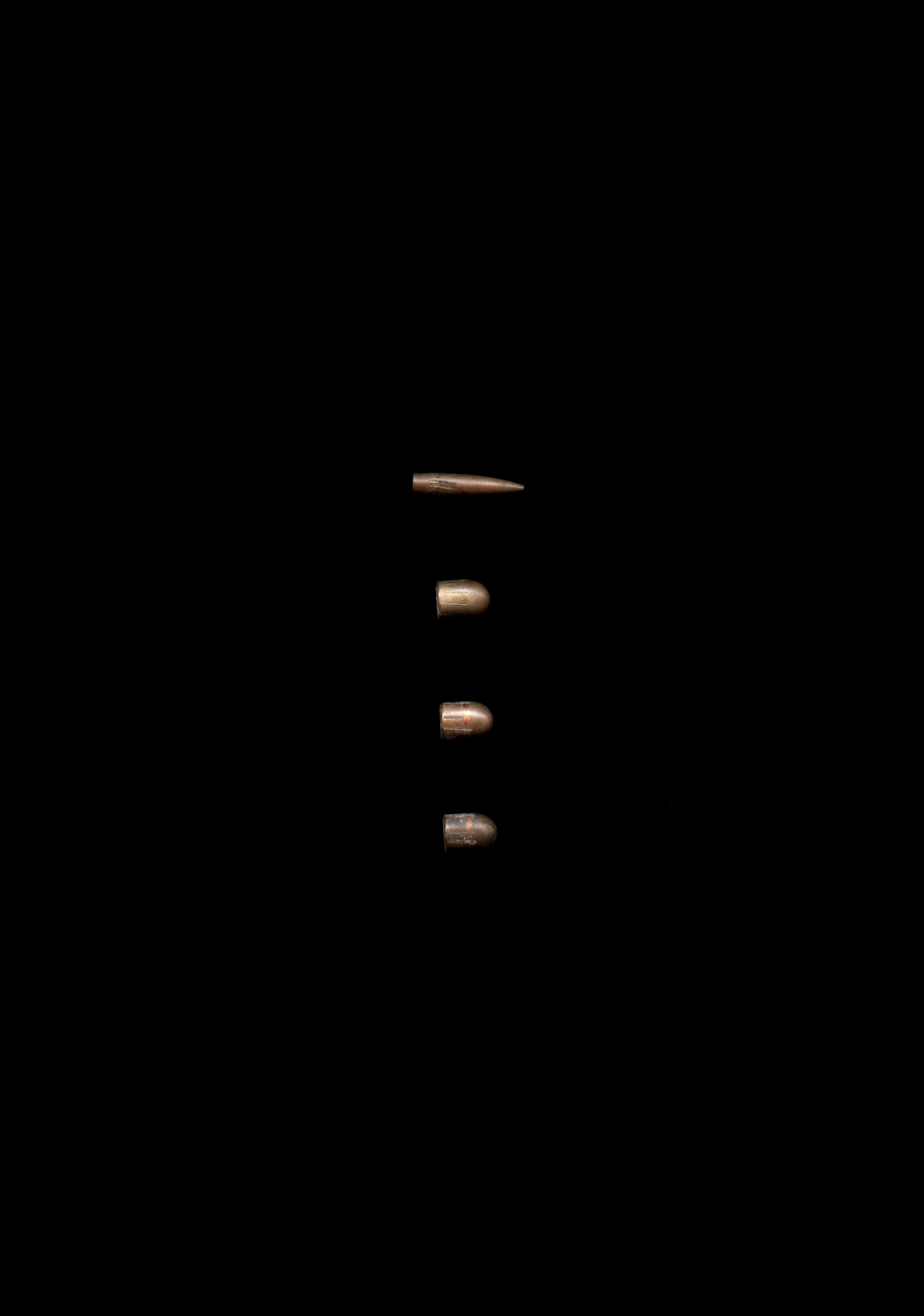

Bullets picked up at the Pravyi Sector Ukrainian Volunteer Corps base in the Donetsk Region: calibre — 5.45 mm; diameter — 5.60 mm; length — 25.5 mm; weight — 3.5 g; muzzle velocity — 915 m/s; effective firing range (AK-74) — 600 m.

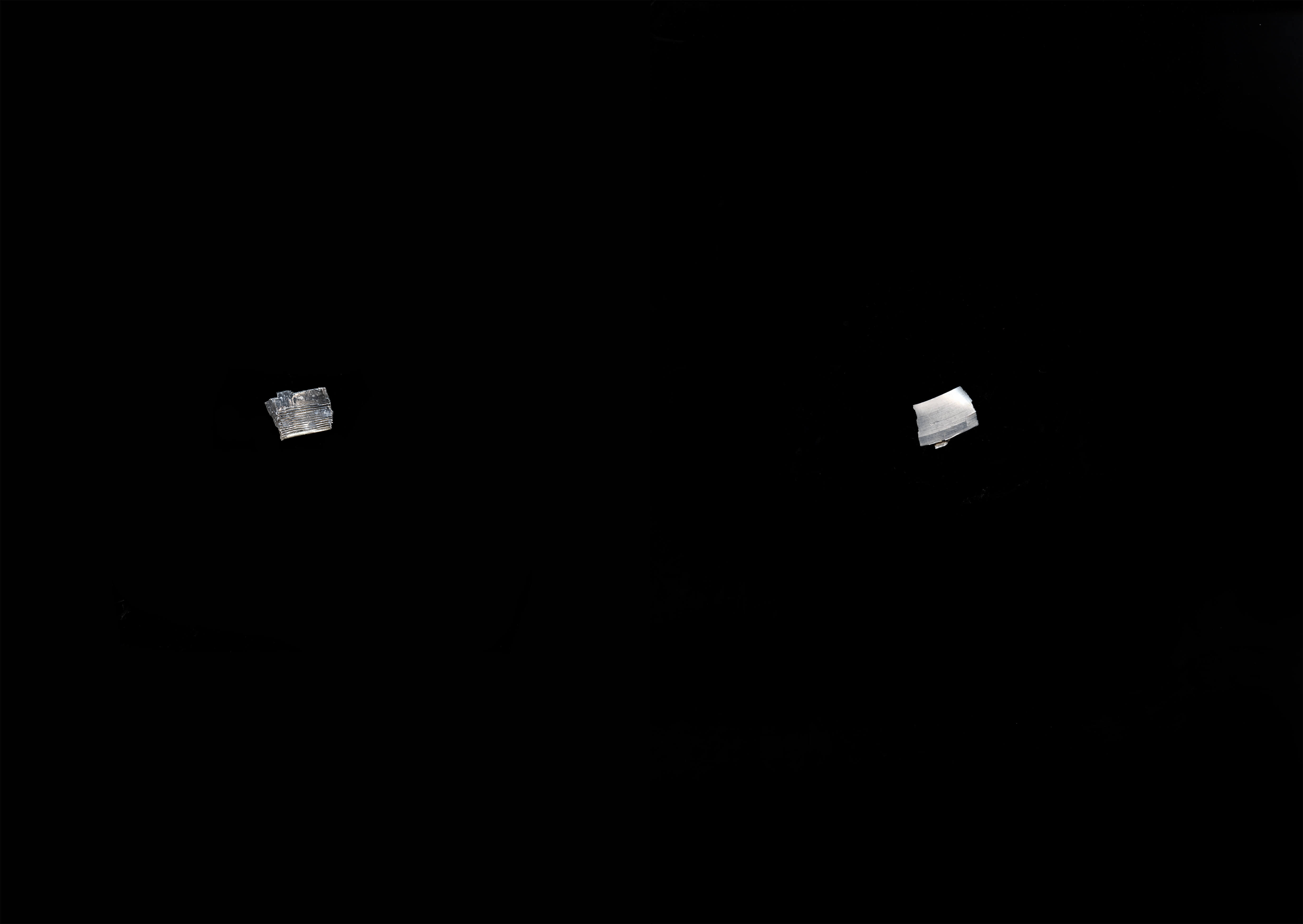

A fragment found in Shchastia, Luhansk Region, (possibly a grenade for VOG-17 automated grenade launcher): weight — 1.9 g; number of fragments — about 100; danger area — 70 m²; calibre — 30 mm; firing range — 1,700 m.

Shchastia in the Luhansk Region became a frontline city. People had adapted to the new situation, trying to live as usual and paying no attention to shelling. On the second day of our stay there, we interviewed the city’s mayor, who told us about what had changed. He got a call about a shelling nearby, during which one civilian was injured. A mortar shell flew into some shop’s open door, and some boy inside caught shrapnel in his stomach. His mother cursed the war. Still, locals feared calling separatists their enemy and the Ukrainian military their defenders.

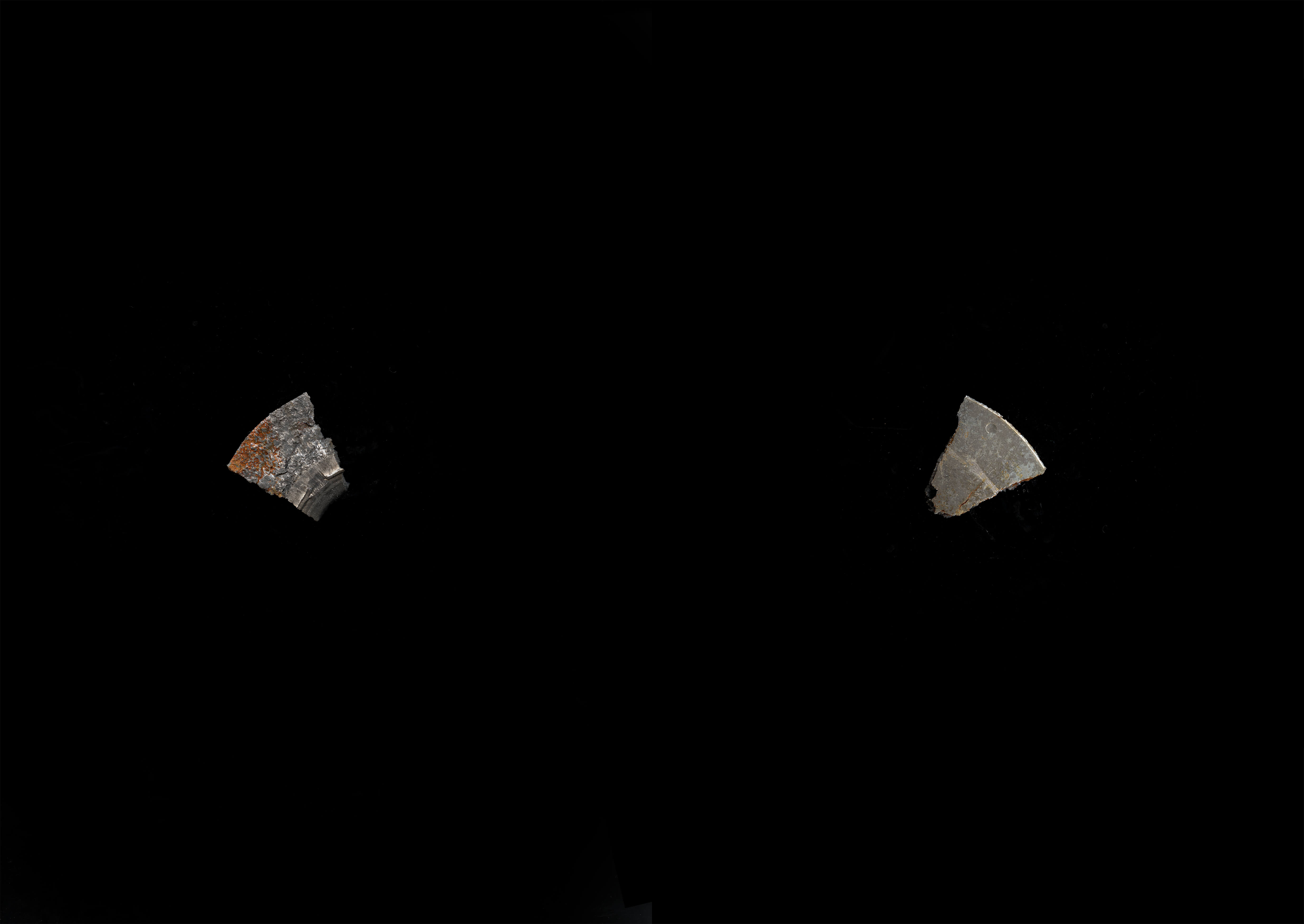

A fragment of a BM-21 “Grad” multiple rocket launcher munition found in Stanytsia Luhanska, Luhansk Region: weight — 135 g; shrapnel count — 3,920; danger area — 1,000 m²; calibre — 122 mm; firing range — 20 km.

They came under shelling the day before. Their checkpoint was hit by Grad rockets, and many people were killed and injured. We weren’t allowed to take pictures on site. So we walked around and soaked in the aftermath of the rocket’s direct impact on the building. The roof was blown off, floor slabs were broken or caved in, doors were blown off or deformed like a tin can, window glass was broken, and partitions were riddled with holes from shrapnel. I found this fragment under my feet on the road. Six months later, I got a chance to witness a Grad shelling up close from a nearby position.

A fragment found in Pisky, Donetsk Region (120 mm mortar): weight — 71.6 g; number of fragments — 3,500; danger area — 1,290 m²; calibre — 120 mm; firing range-7.1 km.

Something fluttered over our heads. A mortar! You have less than a second to make a decision in a situation like that. And there is only one decision — to drop to the ground and crawl away. An explosion! We heard the shrapnel tapping against the nearby roofs, clattering against the walls, and falling on the snow. I crawled into the pit under the howitzer’s spade, where some soldier had taken shelter, and proceeded to take photos of him. “Can you send me the pics?” he asked. “Sure thing!” I shouted back. Nobody was killed or injured that day. Mortar duels were an everyday occurrence, and no house in town had been left undamaged by that time. Only a few wounded dogs roamed the streets — almost all locals had evacuated. Few journalists visited Pisky, and even fewer went further to Donetsk Airport. In six weeks, on the 28th of February 2015, photographer Serhii Nikolaiev would be killed by shrapnel in that town.

A fragment found in Pisky, Donetsk Region (82 mm mortar): weight—46 g; number of fragments — 400–600; danger area — 715 m²; calibre — 82 mm; firing range — 4 km.

Our squad went on 24-hour combat duty in the position. First, the soldiers prepared the position and cleaned mortar shells from snow and dirt. They were short of shells and tried to make every shot count. During the night, the soldiers jumped to their feet upon hearing the alert and routinely, as if just doing their job, picked up the shells and ran to the mortar. The enemy returned fire a few times but wasn’t even close to hitting our position. That was how we spent our day and night. Another squad came to relieve us in the morning. We handed over our position to them and trudged away through the town to sleep in our basement.

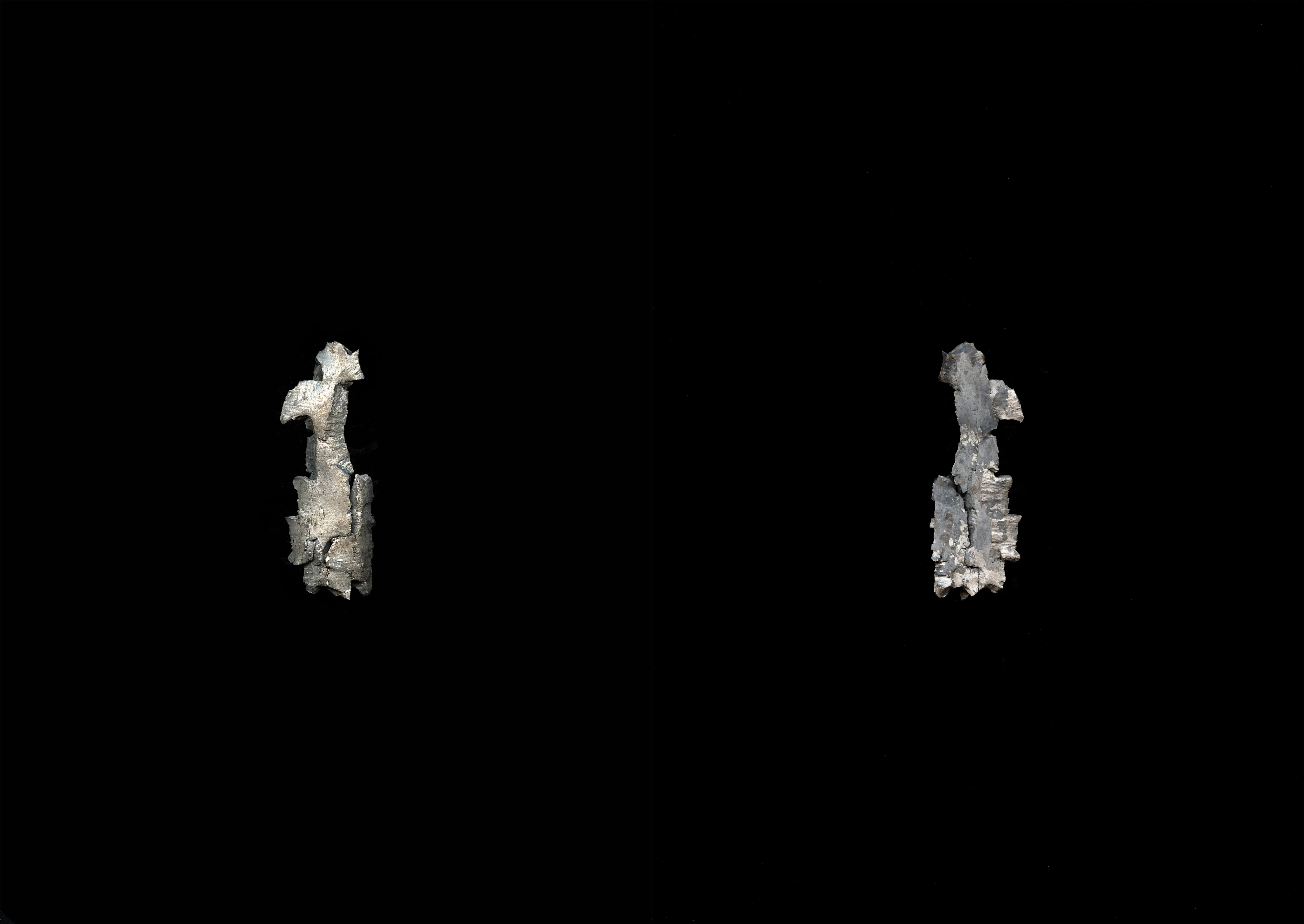

A fragment found in Debaltseve, Donetsk Region (likely a 152 mm artillery shell): weight — 196 g; number of fragments — 3,460; danger area — 950 m²; calibre — 152 mm; firing range — 17 km.

January 2015 saw heavy battles around Debaltseve. The threat of Ukrainian troops getting surrounded was very real, and it felt like it would happen soon. It was at that time that the fourth mobilization wave was announced, and I was enlisted. Army officers read the news in between the lectures, and everyone’s thoughts were with the besieged town. I served in a communications unit far from the frontline and never got to leave it for troop rotation. These fragments were scattered on the floor in one of the corridors of our base — our army officers must have brought them as a souvenir. The vehicles that returned were battered and maimed — shrapnel pierced the aluminium trailers all the way through. Others burned down or were abandoned near Debaltseve.

A fragment found in Debaltseve, Donetsk Region (likely a 152 mm artillery shell): weight — 196 g; number of fragments — 3,460; danger zone — 950 m²; calibre — 152 mm; firing range-17.4 km.

Transport from Pisky rarely went beyond the frontline. The latest was the one that brought me the previous week. It was an armoured off-roader of commander Chornyi — and he drove it himself. The vehicle drifted a couple of times — it was rather heavy. It was time for me to go home already. Mother kept calling me, asking, “Where are you?” “In the ATO,” I replied. “Are you taking photos?” “Yes, I am.” On the day I left, we went to say goodbye to the soldiers. Before we could so much as step away from the car, two explosions thundered nearby. A brick fence 10 metres from us was blown to pieces. We dropped down into the snow and crawled under the car. Another volley and another two blasts. We jumped to our feet and rushed to the basement. The shock wave threw the soldier who came in after us against the ceiling. Everyone survived, but the kitchen was no more. The shelling ceased as abruptly as it began.

A fragment found in Debaltseve, Donetsk Region (a 122 mm artillery shell, likely a high-explosive fragmenting munition): weight — 24 g, number of fragments — 2,350, danger zone — 800 m², calibre — 122 mm, maximum firing range (D-30 howitzer) — 15 km.

It had been three days since we left Kyiv to deliver volunteer aid to soldiers on the frontline. We planned to deliver warm clothes to our friends in Pisky and then make our way through Kramatorsk and Sloviansk to Volnovakha and Mariupol. It was my third visit to Mariupol, but I had no chance to photograph hostilities the previous times. The Donbas Battalion lost some of its soldiers when it came under shelling in the city the day before our arrival. It happened during yet another ceasefire. Not everything happening on the frontline is covered in the news or becomes publicly known.

Bullets picked up at the Pravyi Sector Ukrainian Volunteer Corps base in the Donetsk Region: calibre — 5.45 mm; diameter — 5.60 mm; length — 25.5 mm; weight — 3.5 g; muzzle velocity — 915 m/s; effective firing range (AK-74) — 600 m.

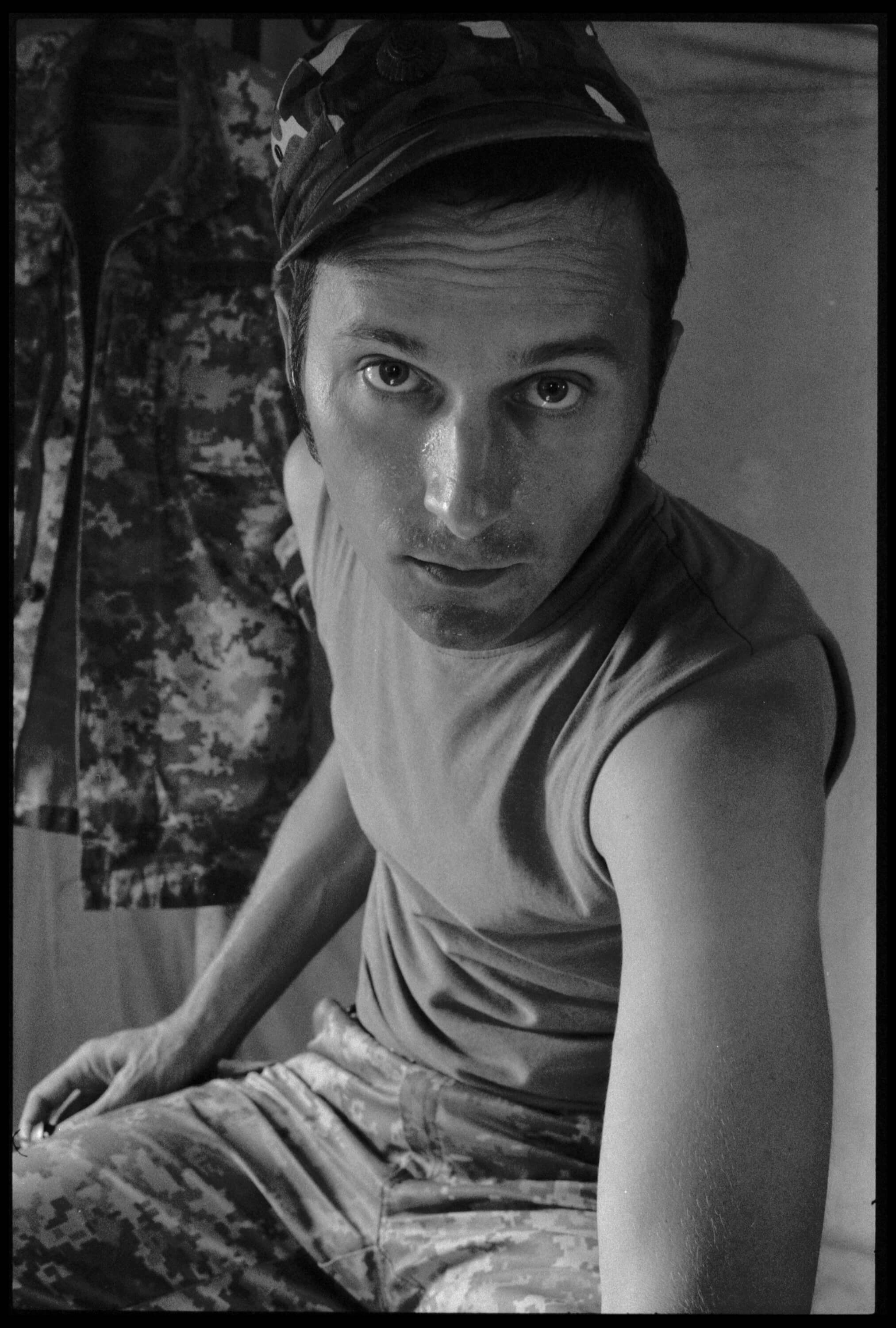

The Ilovaisk Cauldron had just happened, and everyone focused on helping out and volunteering. Many volunteer battalions popped up. I took cinematographer Leonid Kanter to film the Pravyi Sektor Battalion, which turned out to be the best organized of those I had seen. The enemy was legit scared of it. I didn’t go into the contact zone, remaining at the base to train over the following week. I picked up these bullets and cartridges at the shooting range there. Also, I got to meet the soldiers who went on to defend Donetsk Airport later. Who was I at the time? A soldier. A driver. A journalist. A volunteer.

A fragment found in Debaltseve, Donetsk Region (a 122 mm artillery shell, likely a high-explosive fragmenting munition): weight (from top to bottom and left to right) — 91 g, 14 g, 16 g, 31 g, 34 g, 67 g, and 17 g; number of fragments — 2,350, danger area — 800 m², calibre — 122 mm, maximum firing range (D-30 howitzer) — 15 km.

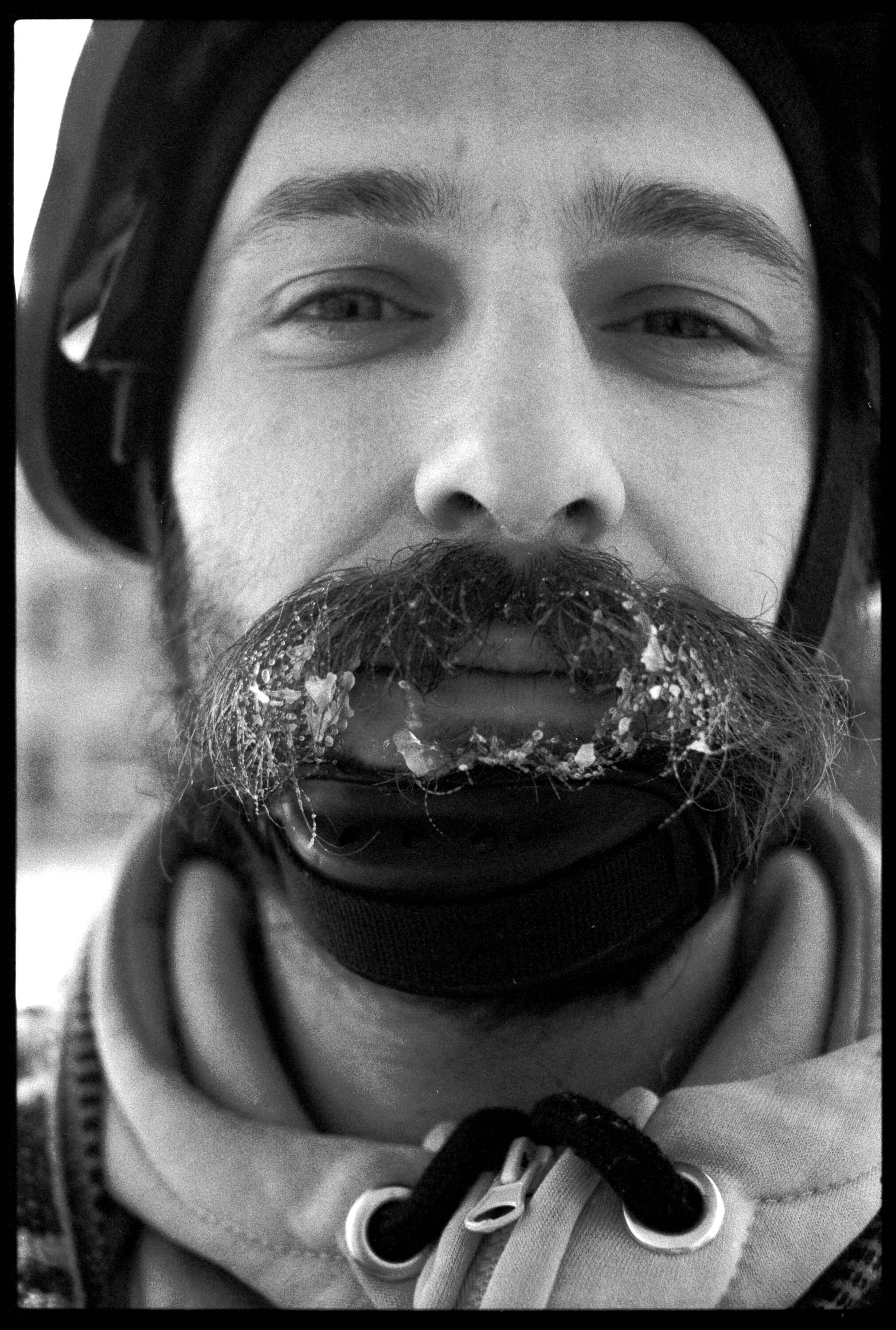

This is my friend Ivan Havrylko, he has two children. He used to work as a land surveyor and was assigned the codename Geologist in the military. We met in the summer of 2007—both young and enthusiastic, and Ivan even looked like a true Cossack. On the New Year’s Eve of 2015, I visited him in Karlivka, where he was stationed. It was calm there at the time, the town was far from the frontline, and the soldiers were busy setting up positions, digging and insulating the dugouts.

On our way, we passed Stanytsia Luhanska, Novoaidar, Shchastia, and Triokhizbenka. Activist human rights advocate Kostiantyn Rieutskyi drove two journalists and me there. Our goal was to film a news story about the life of civilians during the war in Ukraine, which continued for six months at that time. However, Kostiantyn went there as a reporter and cameraman to interview officials, teachers, the military, and civilians. To this day, he hopes to return to his native city, although he has begun a new life in Kyiv already.

Activist and cinematographer Leonid Kanter came to Donetsk Airport to film his second documentary — The Ukrainians. He left his family behind to film the Pravyi Sector Ukrainian Volunteer Corps, which defended Donetsk Airport and the nearby town of Pisky. He wanted to show the entire world, which saw only Russian propaganda at the time, that Ukrainians were ready to fight the enemy army no matter how strong it seemed.

Triokhizbenka became a frontline town. Separatists often shelled it from their positions behind the river as the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Aidar Battalion kept holding its outskirts. Electricity outages were frequent, locals lived in basements, and the gas supply had been shut off. We had finished filming and were on our way back. Having noticed the soldiers standing on the road among the fields, we approached them to ask for directions. As we learned, those were the Novoaidar District Office of Internal Affairs policemen patrolling the territory. After a short chat, we were invited to come to visit. Their superior and the group’s commander was Leonid Pantykin. When the town was captured, he evacuated about 500 children from the occupied territory.

I was in Mariupol again. I was ready for an extended stay at that time. One day, I met a foreigner who drove there in his own car all the way from Germany. He said he wanted to stop the war and intended to go to the president and separatist commanders to talk them into stopping the hostilities. I was afraid to leave him on his own in the city because he was as naïve as a child. Together, we went to the local hospital to visit soldiers. There were a few lightly injured servicemen there — the German treated them to candies and gave them children’s colouring books for some reason. He was weird. He saw this war as a struggle between good and evil. We took keepsake photos in a photobooth and parted ways since I decided to return to Kyiv.

A fragment found in Stanytsia Luhanska, Luhansk Region (a 23 mm B3-A bullet jacket): weight — 4 g; calibre — 23 mm; bullet weight — 175 g.

When the war in the East of Ukraine started, Ukrainians started arming themselves and banding together as volunteer battalions. As a journalist and volunteer, I was in many such battalions fighting in Donbas. In January 2015, however, I was mobilized and joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine. I was assigned to a comms unit. At first, I tried to get transferred to a unit fighting on the frontline to serve as a press officer. However, it was a new institution, and it lacked coordination. There were people on the local level who helped journalists on their own accord and under their commander’s auspices.

New and best