Groundbreaking Work: Photographs Printed with Soil

A Ukrainian photographer born in Shchaslyvtseve, Kherson Region, which is currently under Russian occupation. His works were published in Vogue Italy, Vogue Portugal, Vogue Greece, and Harper’s Bazaar. He lives and works in Kyiv.

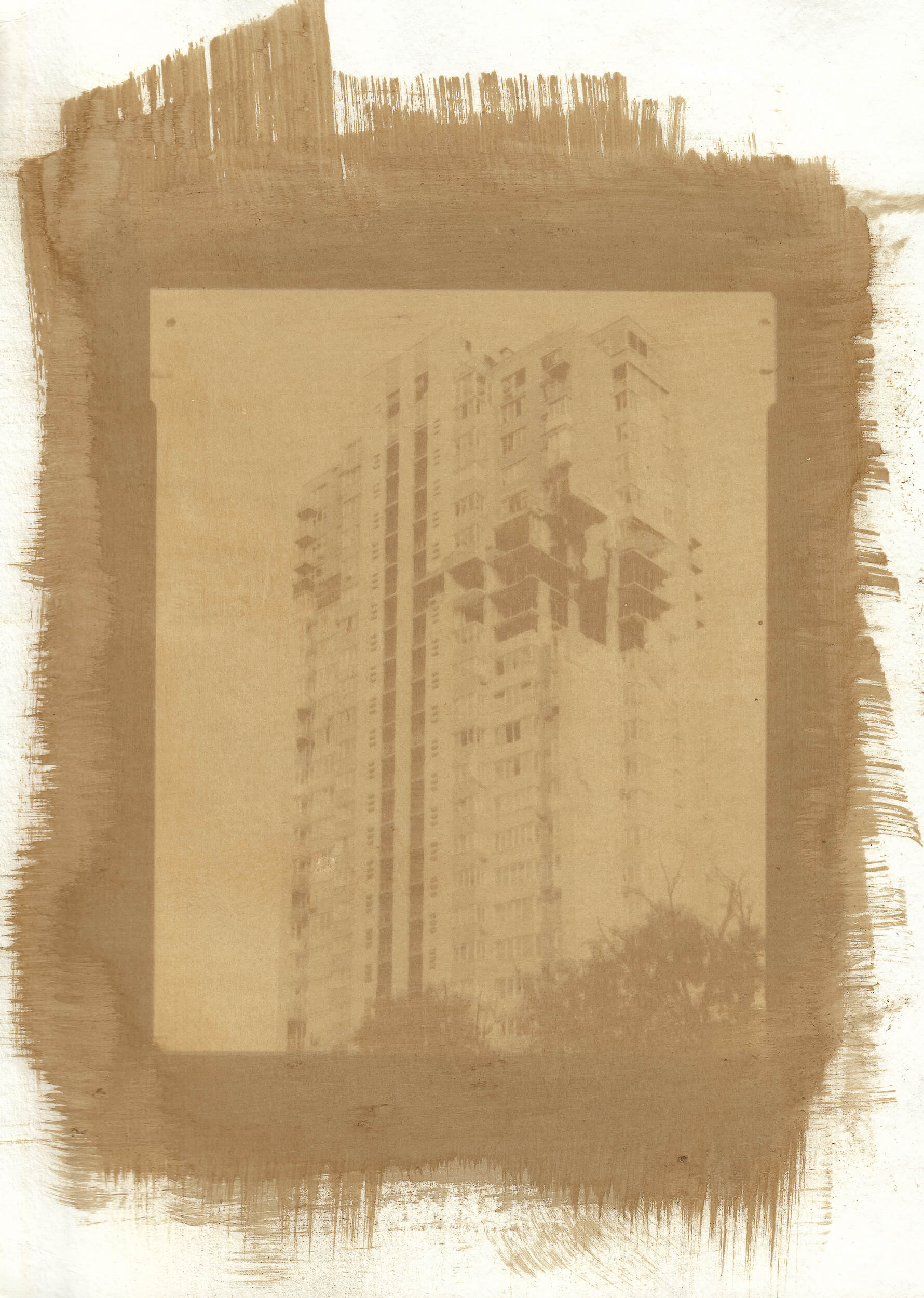

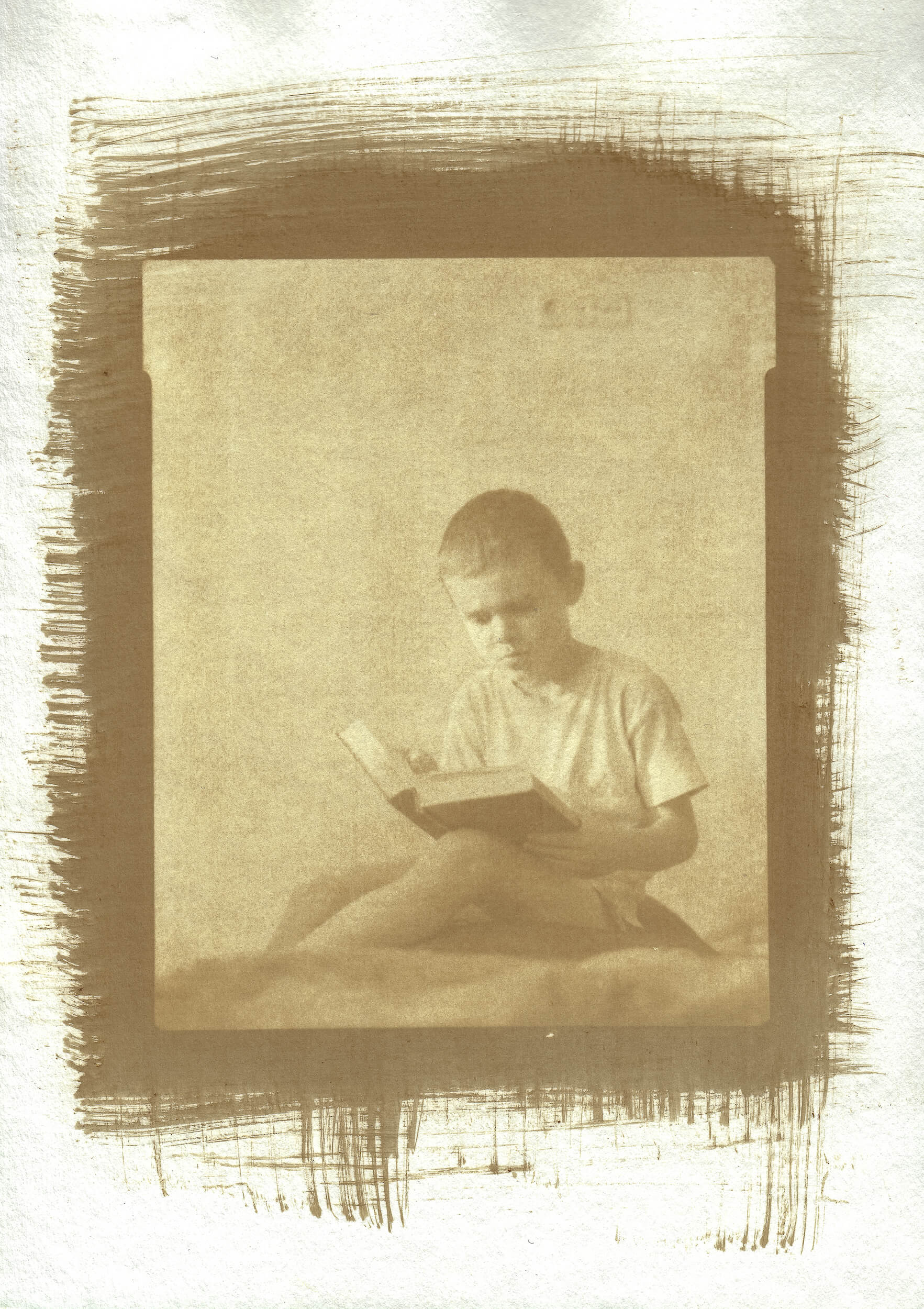

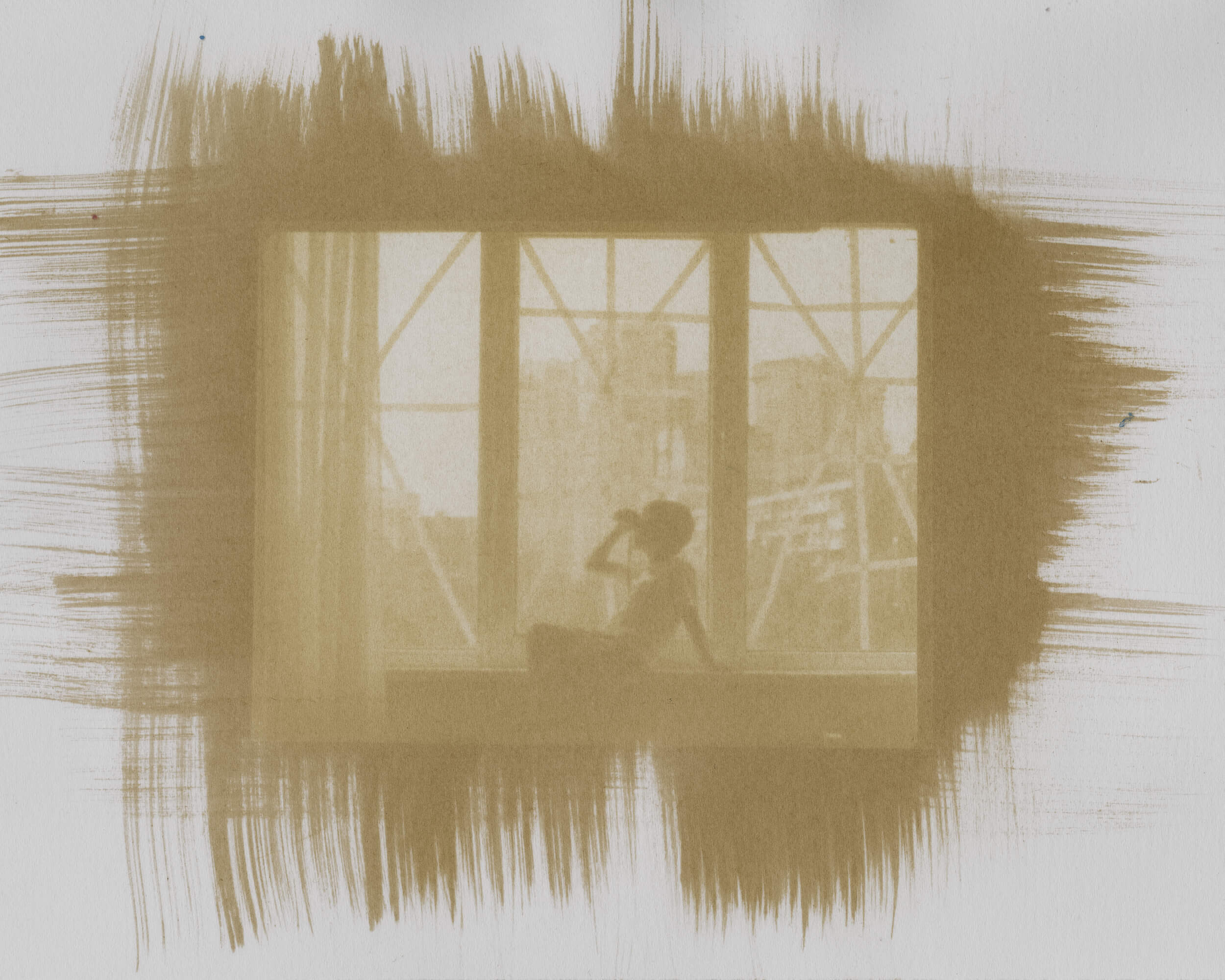

— Over the first two months of the full-on invasion, I hardly took any photos at all. The reasons were multifold. First of all, however, I needed to realize what to document and talk about. In a while, I focused on the feeling of war as experienced away from the active hostilities, on the experience currently perceived as a norm, although it, in fact, isn’t.

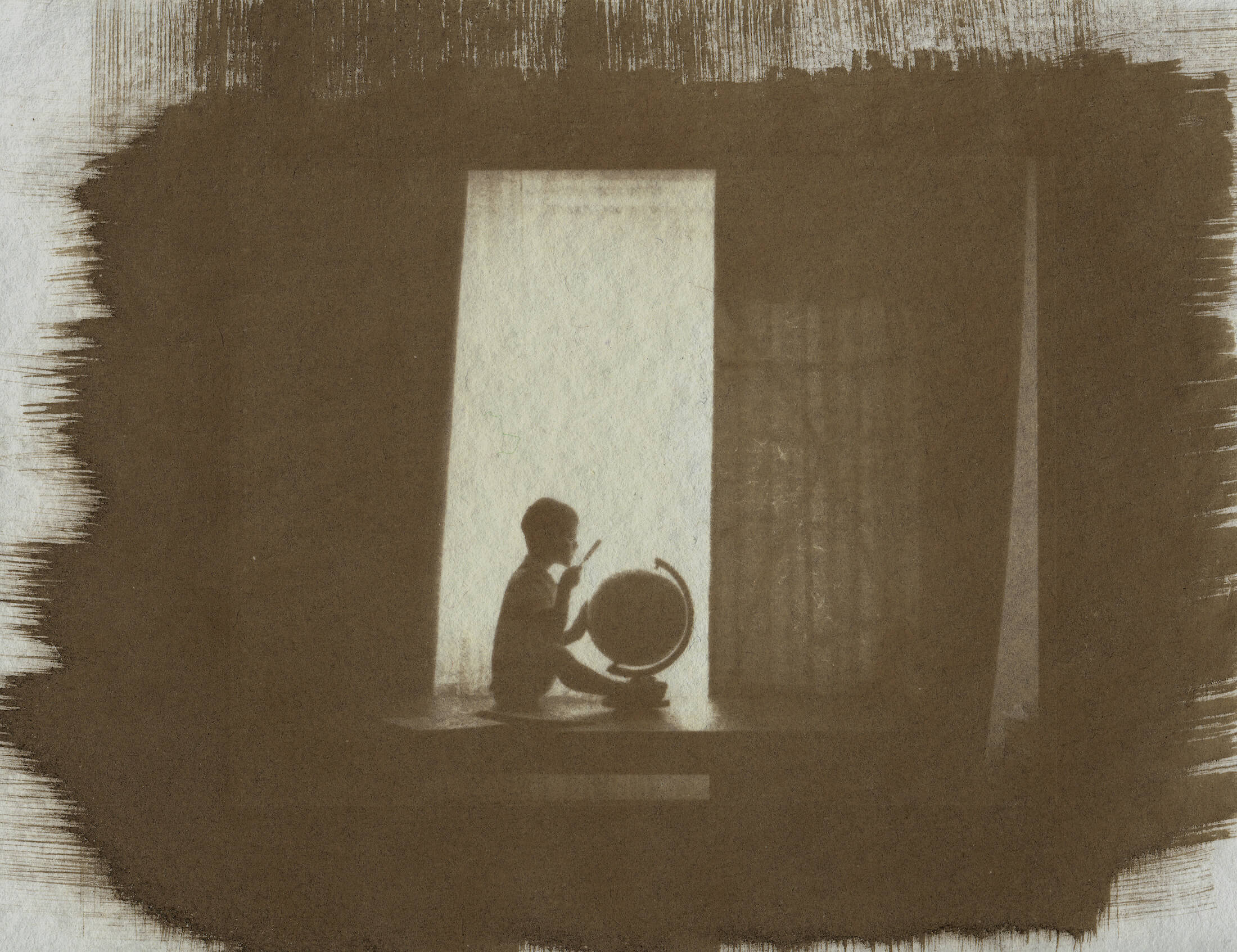

Like, we pass a house destroyed by a rocket on our way to get groceries, and it shocks us no longer. The children’s songs explaining why they should stay calm in the bomb shelter are no longer shocking to us. War is becoming just another aspect of our lives — we are always trying to make it somewhere between the air raid alarms. Sleeping in one’s bathtub is nothing unusual now. It no longer scares us.

War is becoming just another aspect of our lives — we are always trying to make it somewhere between the air raid alarms.

At the same time, my dad and some of my relatives are still in the occupied part of the Kherson Region. I keep reading the news every day and get worried every time my dad doesn’t pick up after two line rings. I do rejoice every time a new city or village gets liberated, but I also realize the price we pay for it every day. At times, I feel desperate, but I donate money for another Bayraktar or just help the people I know and then feel like I’m part of a strong society. Also, I get childishly upset over having no strength or means to end the war ‘tomorrow’.

Therefore, I decided to photograph this mix of feeling this new norm and realizing it’s not normal.

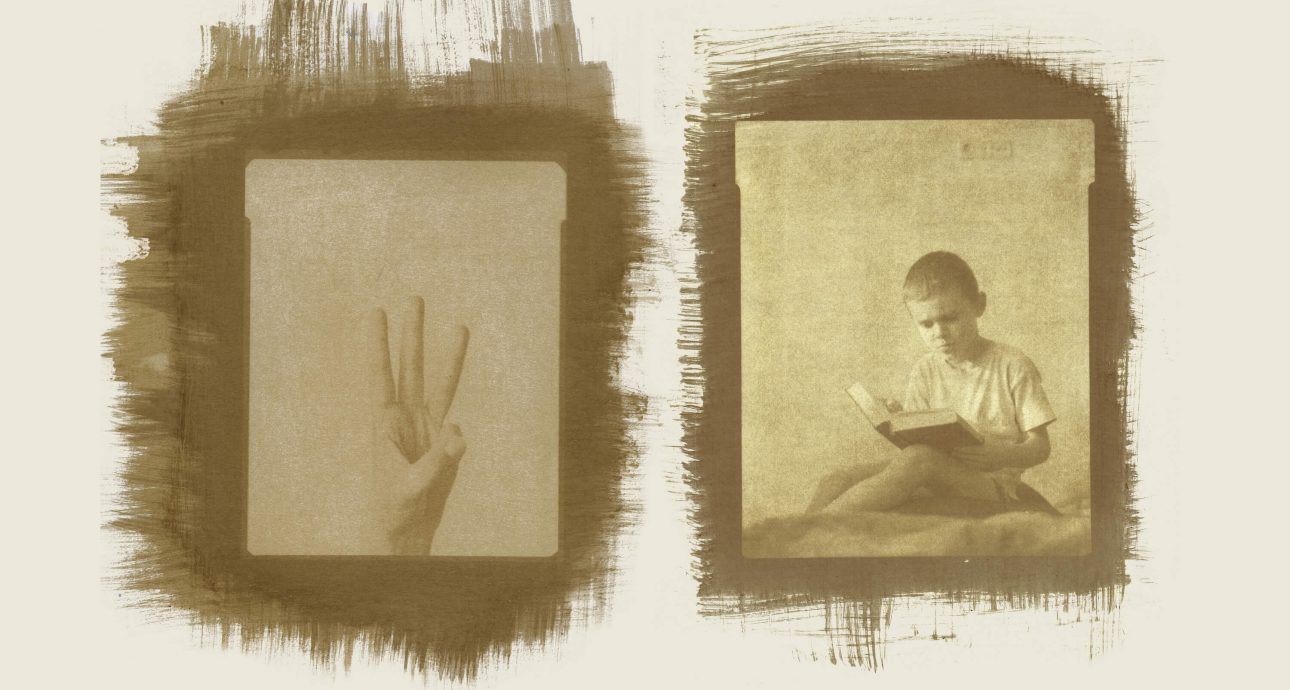

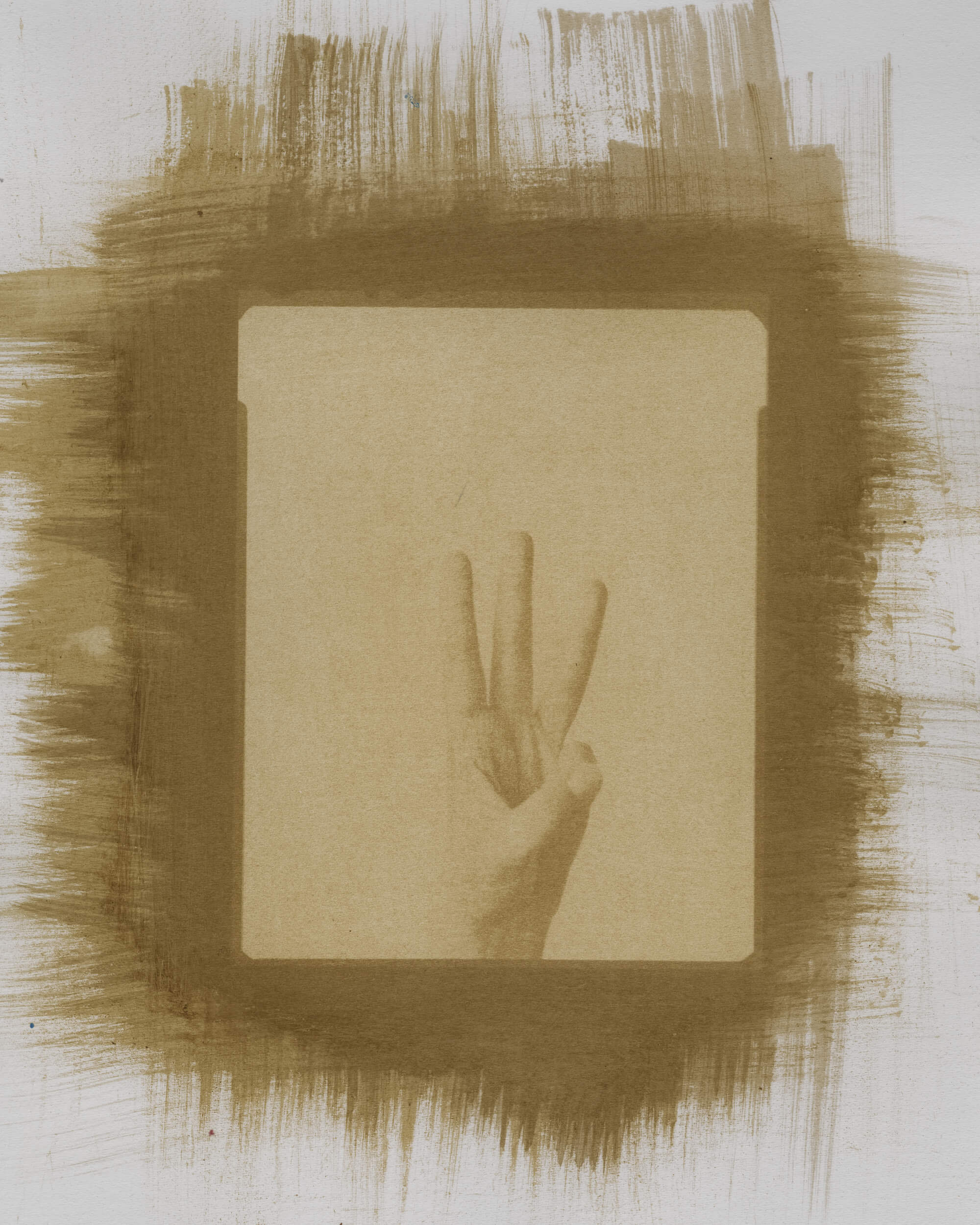

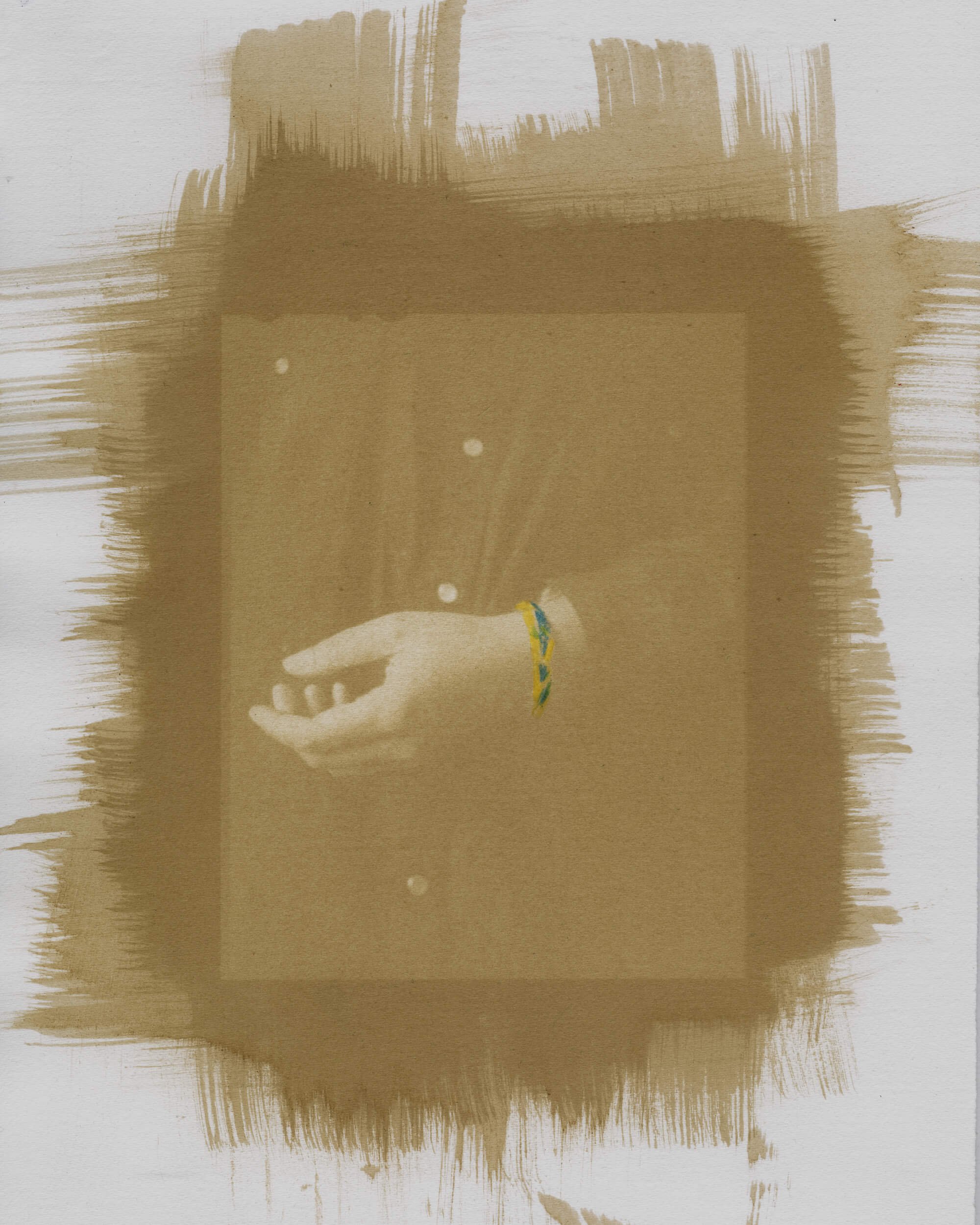

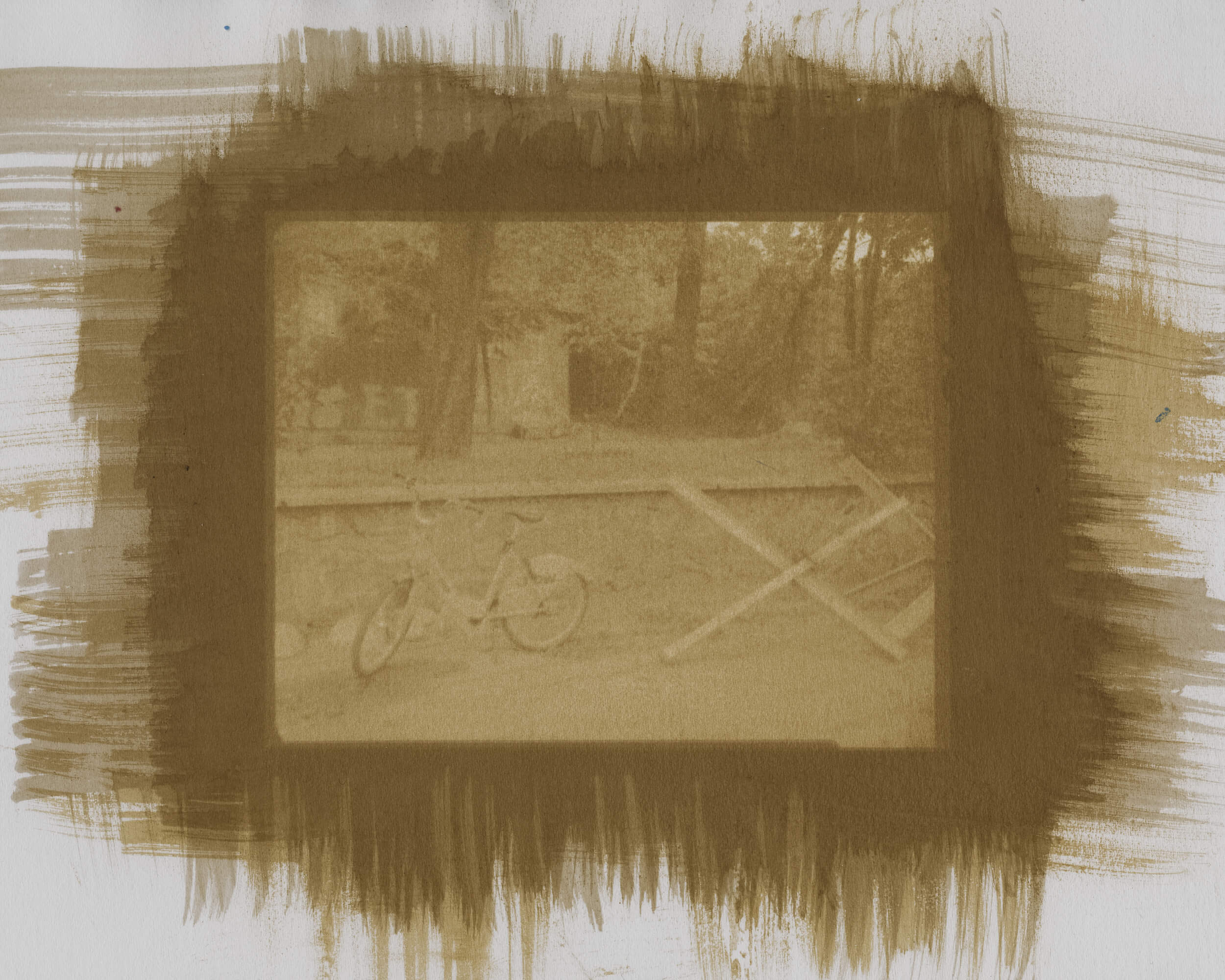

This is why I take pictures of myself and my family. Because invading somebody’s private space in times like these seems inappropriate and difficult to me. Besides, over the first weeks of the war, we didn’t even leave the grounds of our residential complex, so I wanted to capture how that period felt.

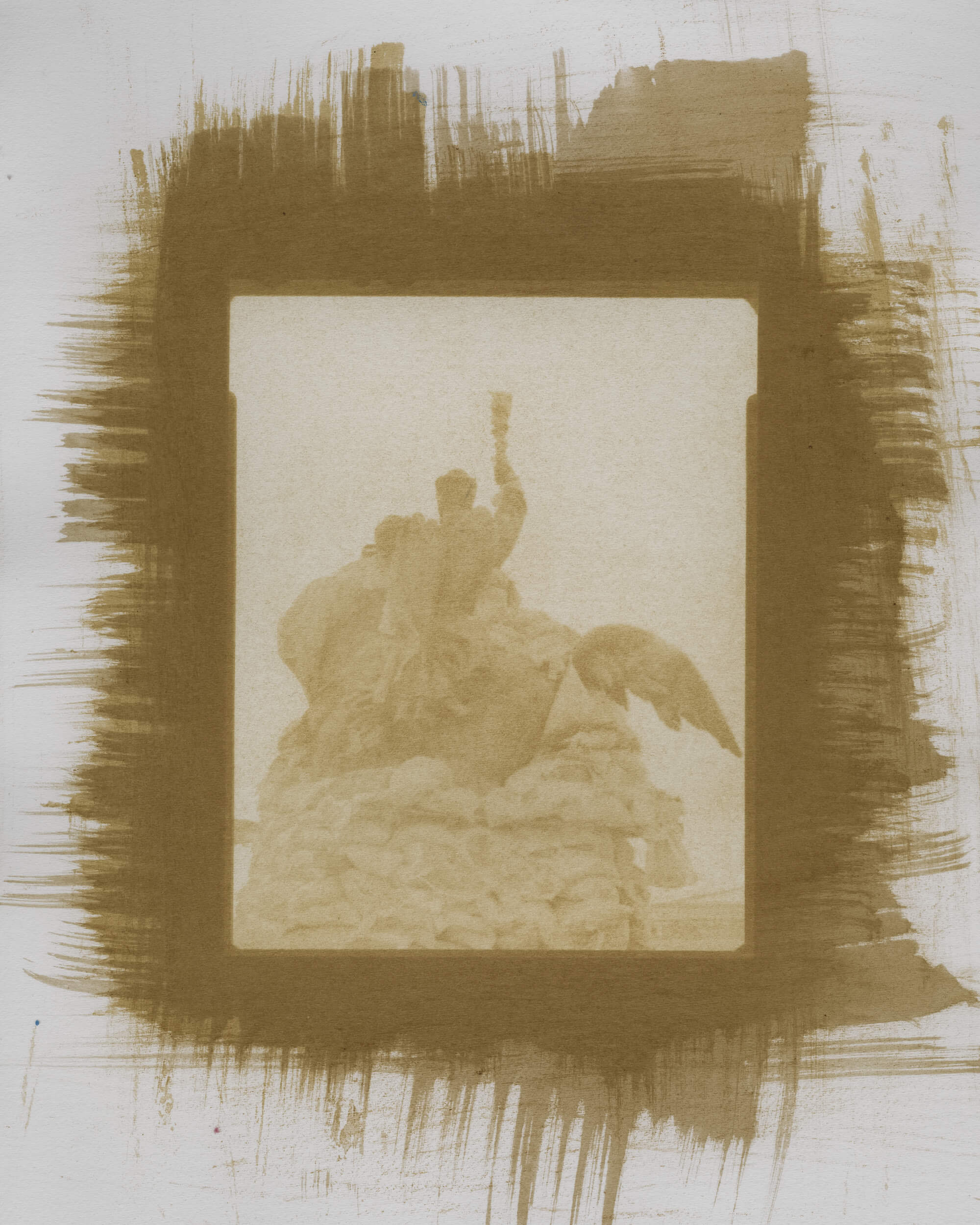

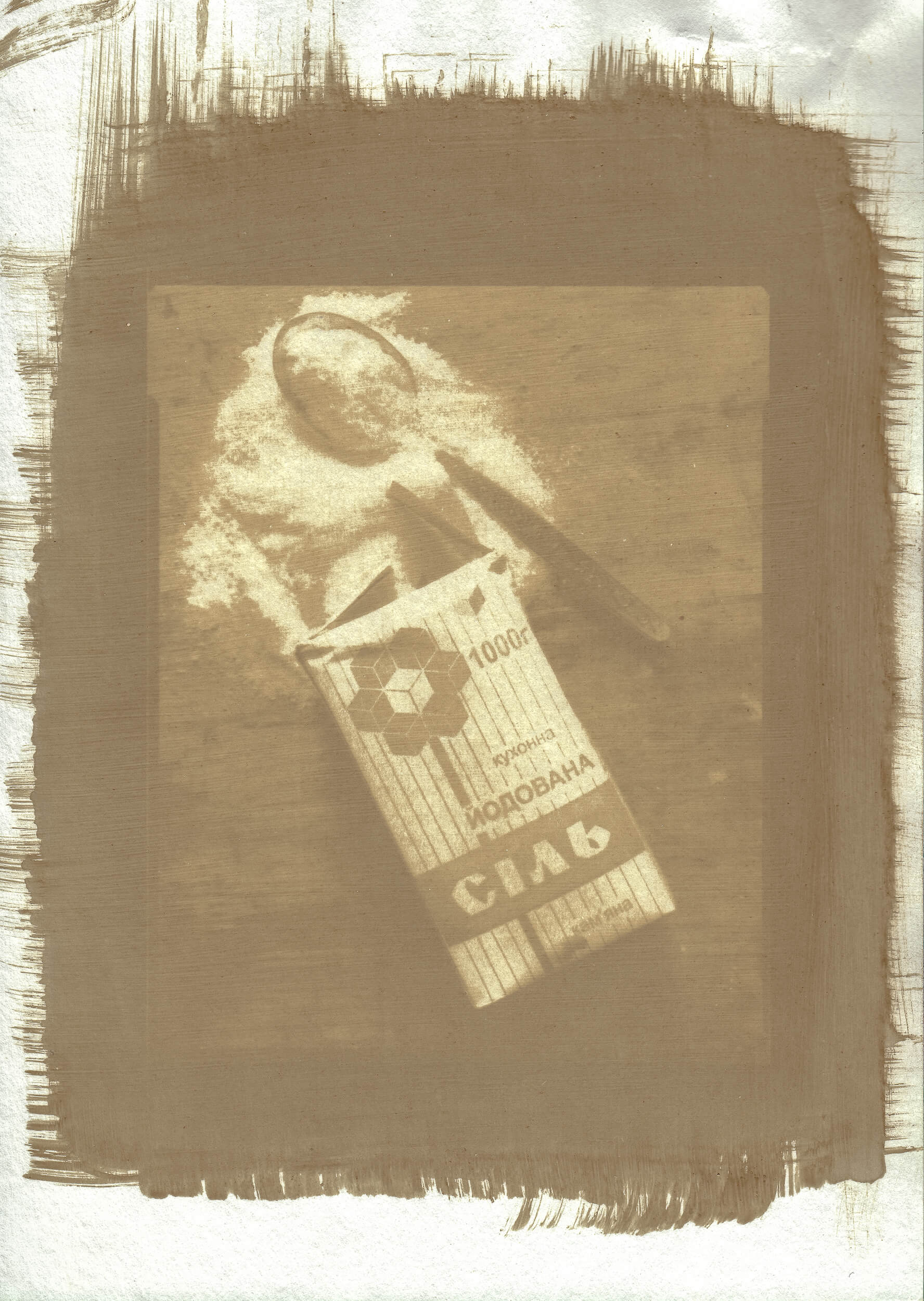

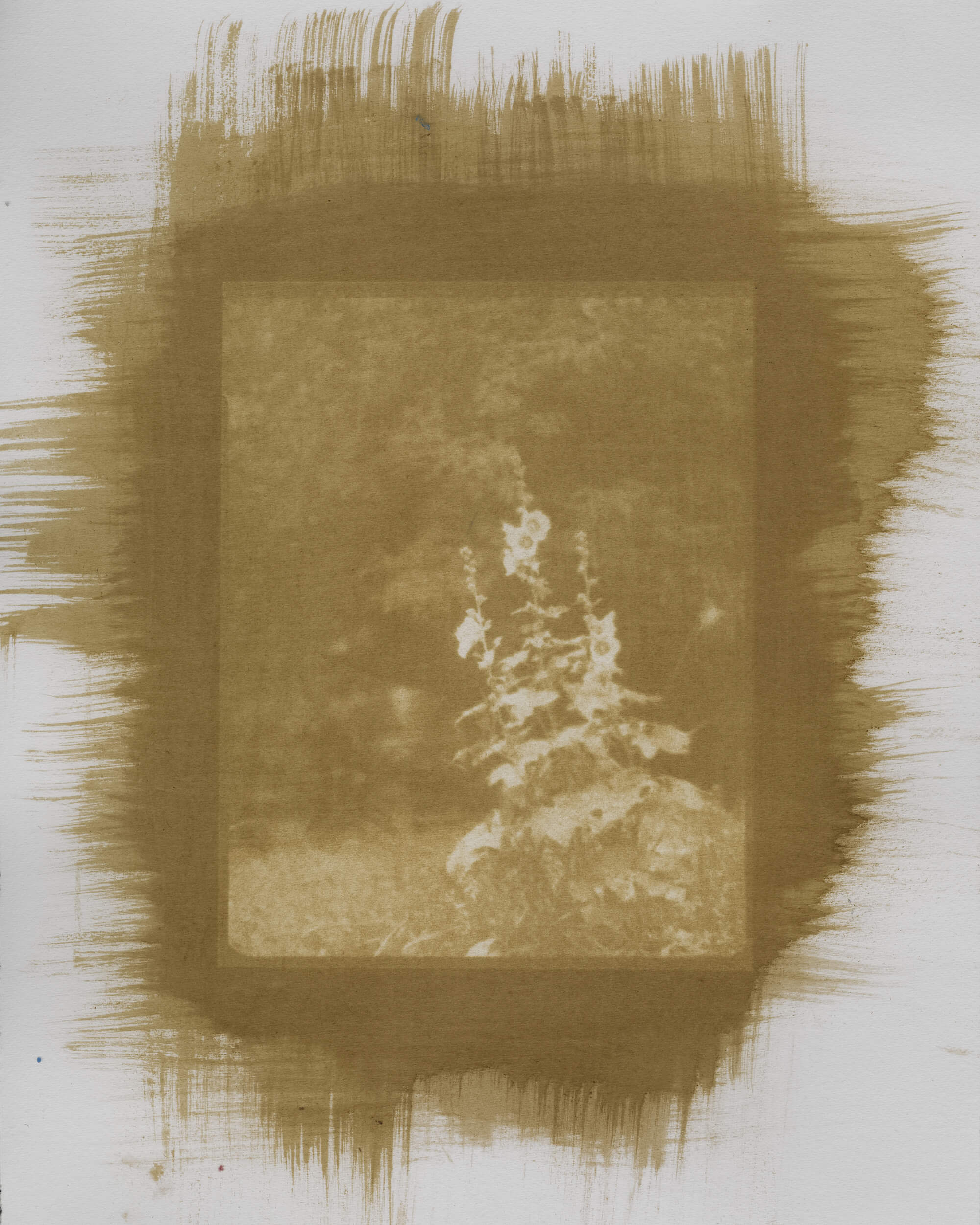

It was important to me to create some material objects. The photos are evidence of those memories and feelings, so I decided to print the photos I shot on film with soil. At first, it didn’t occur to me to use it as a pigment — I got the idea only when I received a copy of my mother’s death certificate. It dawned on me I didn’t know for sure whether I would see her grave with my own eyes. I refused to believe that I would lose the place where I was born and raised, my land, for a long time. On the other hand, I had to admit that I was where I was.

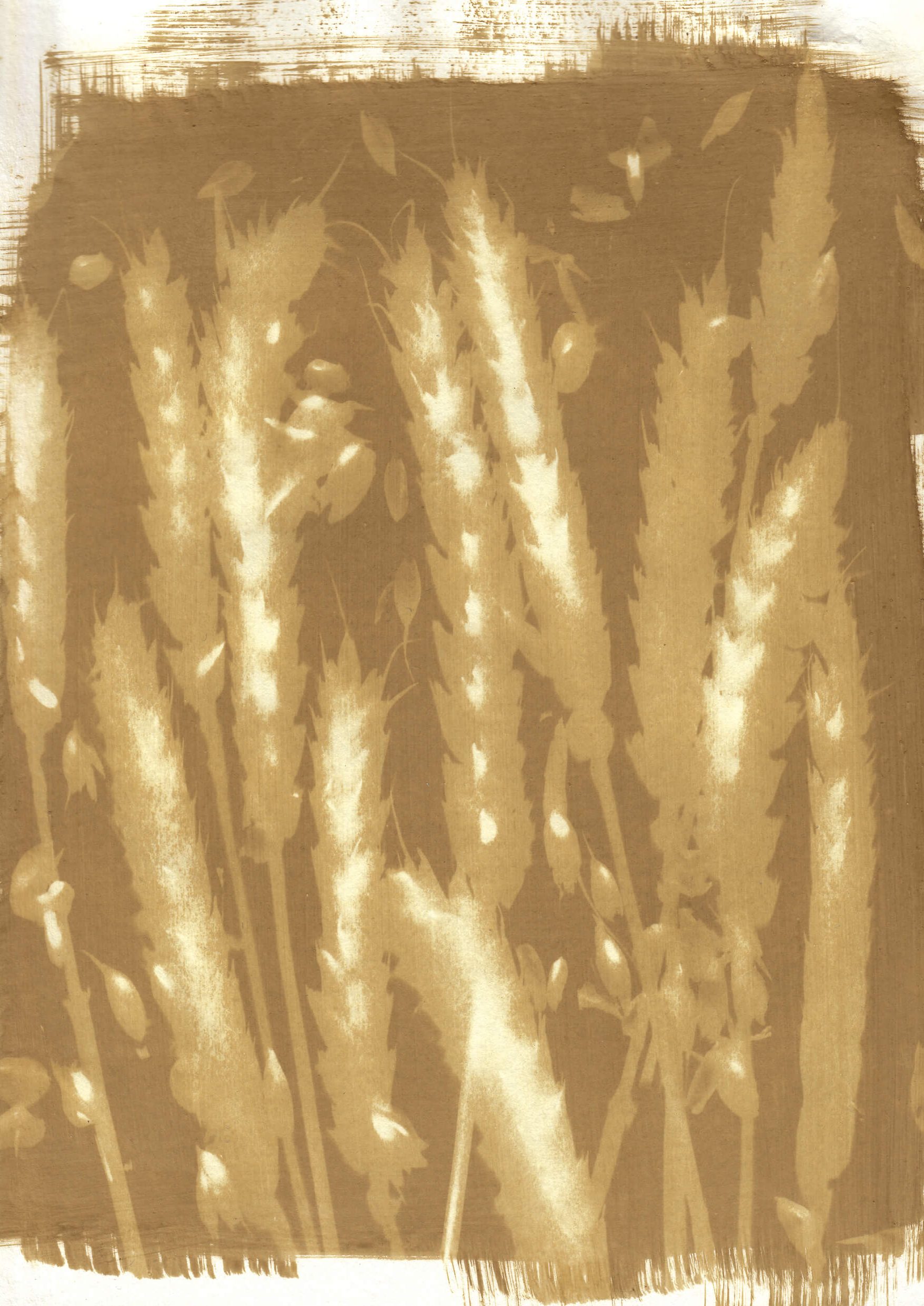

Therefore, I started making prints with the earth that took near the house where I live. This project is about my dream of photographing the deoccupied Kherson Region, the land of my parents, someday and printing those photos with the medicinal clay from Lake Syvash.

This project is about my dream of photographing the deoccupied Kherson Region, the land of my parents, someday.

To print photos, you need to mix Arabic gum, basically tree sap, poisonous ammonium dichromate (it is light-sensitive), and pigment — in my case, it is soil. After being exposed, the photo is washed with water, and the poison goes away with the Arabic gum residue. Only the picture imprinted by the sap and soil remains. In my view, this process is an on-point metaphor for the war itself.

My goal is not to document the war. Rather, I am writing a poetic outline about all the emotions I go through.

The picture imprinted by the sap and soil remains. In my view, this process is an on-point metaphor for the war itself.

New and best