“One Moment He’s Alive, the Next Moment People Shoot in the Air at His Funeral”: Vladyslav Krasnoshchok’s Documentation of the War

An artist from Kharkiv. Studied at the faculty of dentistry, worked at Meshchaninov Kharkiv State Clinical Hospital of Urgent and Emergency Care. In 2010, he joined the “Shylo” group alongside Serhiy Lebedynskyi, Vadym Trykoz, and Vasylisa Nezabarom. Works with documentary photography, anonymous archives, hand coloring, printed graphics, and street art.

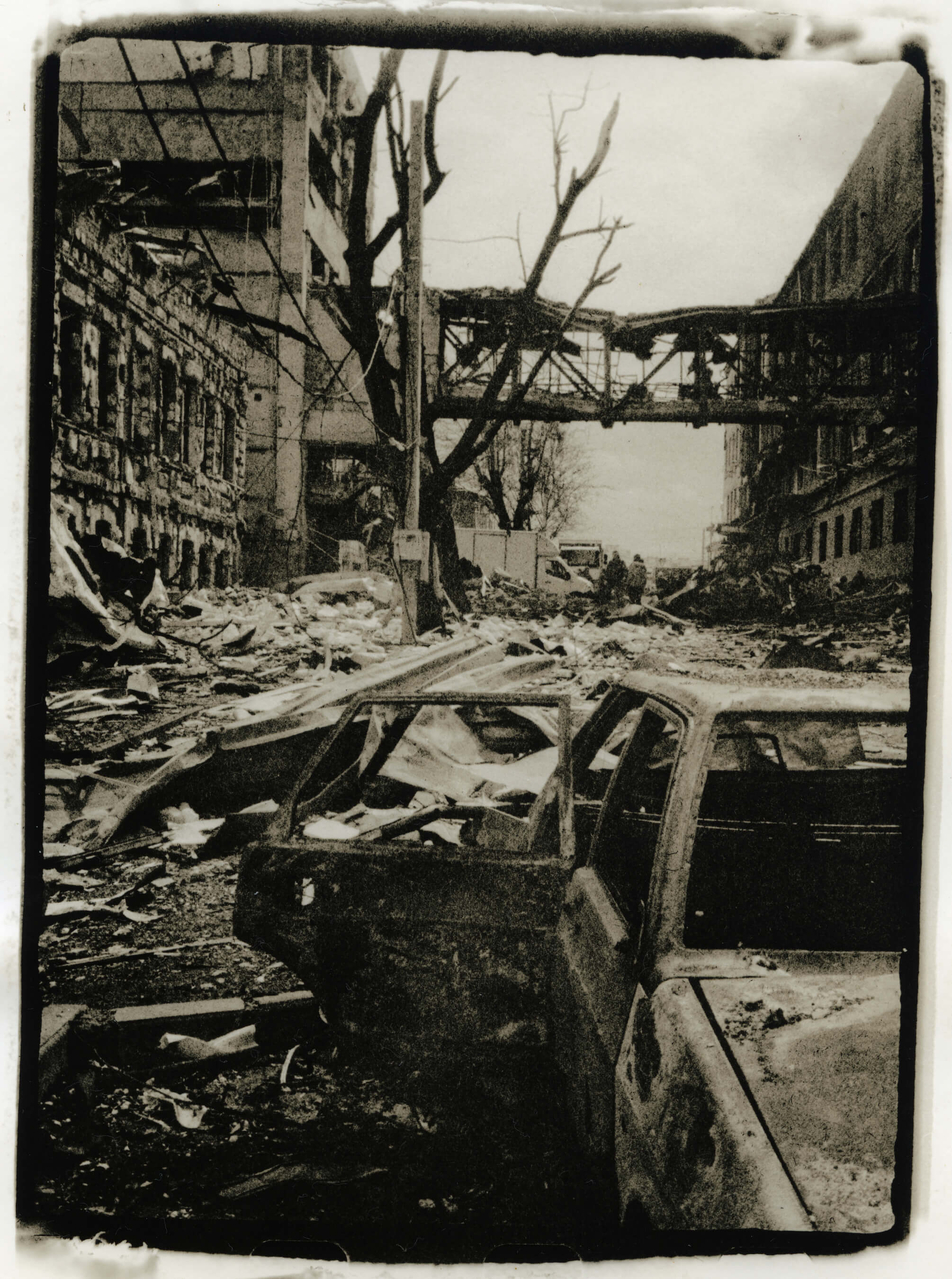

— Lately, I was shifting away from photography towards painting, but now I’m back. When the full-scale war started, no one came to work, me included. We were shocked during the first week, a lot of people fled Kharkiv. I realized, that I would not be able to work insomuch, so I decided to take photos. I always wanted to document war, but I never thought that it would happen in my city. I planned to document events in Kharkiv only, but eventually went to the Kyiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions. That’s when I decided to go to as many places as I could.

I used to take photos without accreditation. But it was dangerous: our military and territorial defense were ready to take you down for pulling out your camera. Everyone was jumpy in the first weeks. One time, we went to the north of Saltivka together with volunteers, I started filming, and got under fire immediately. After that, I got myself accreditation.

We went to the north of Saltivka together with volunteers, I started filming, and got under fire immediately.

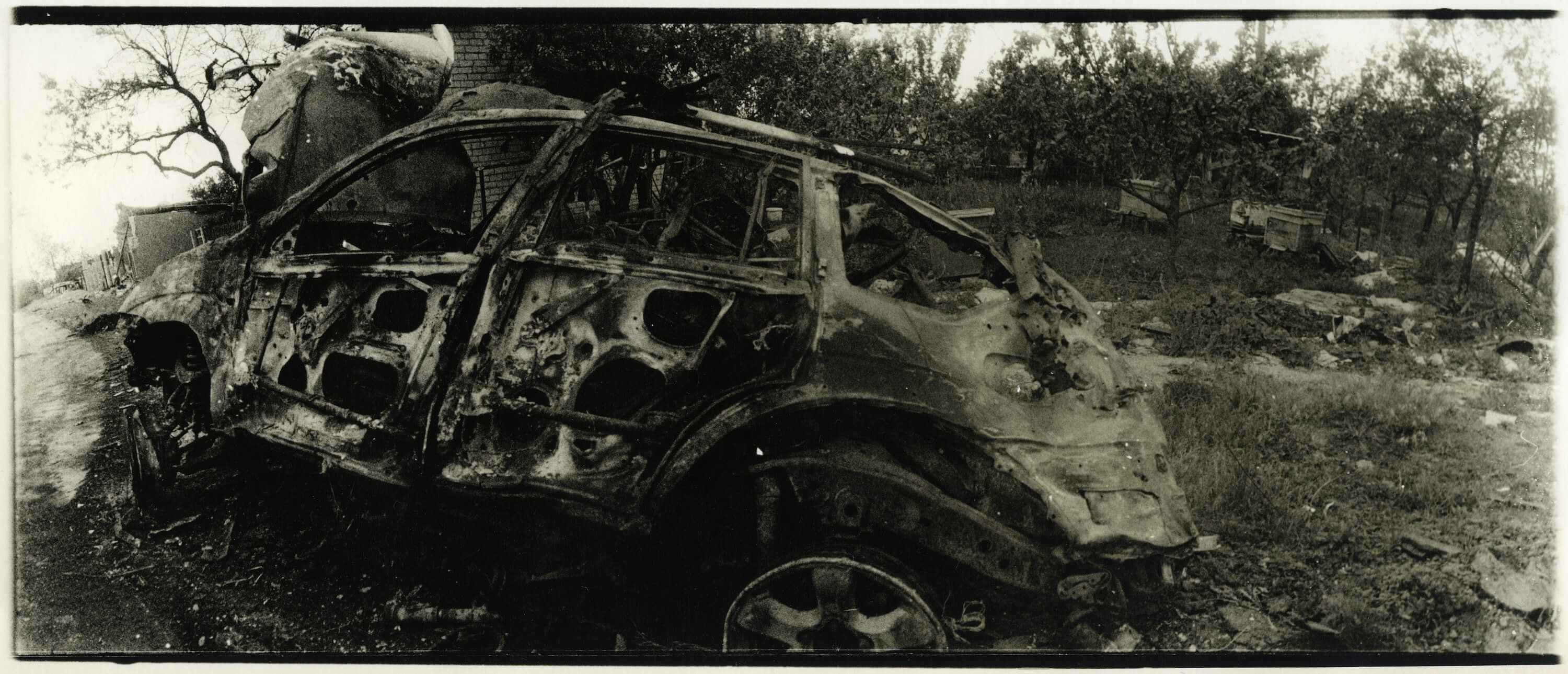

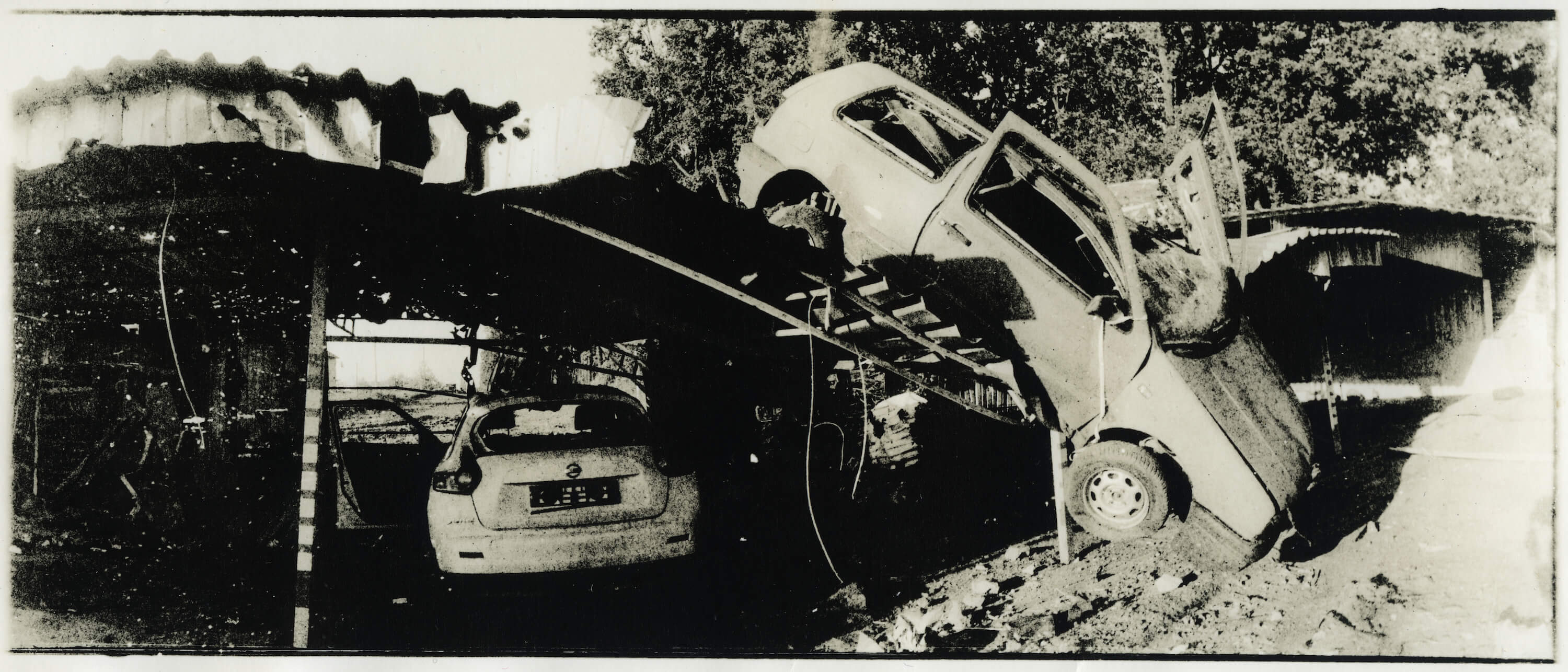

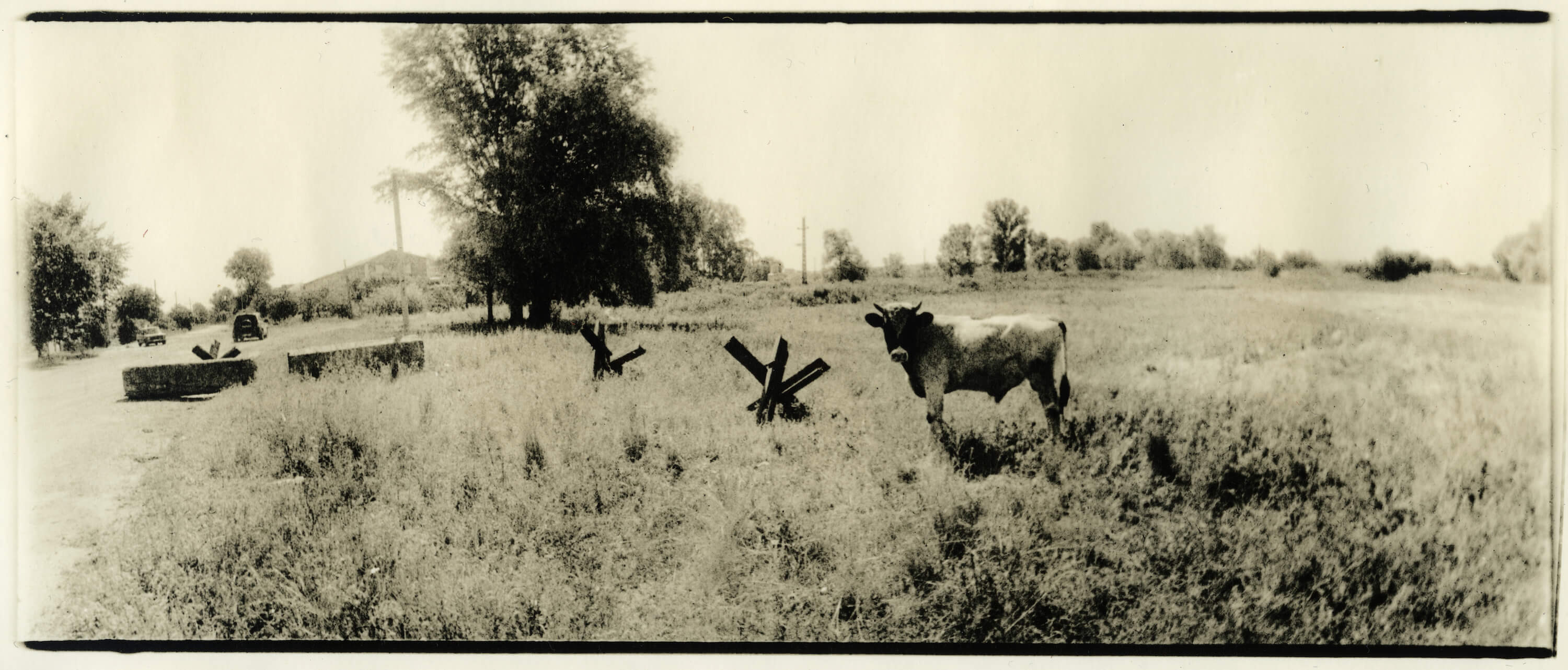

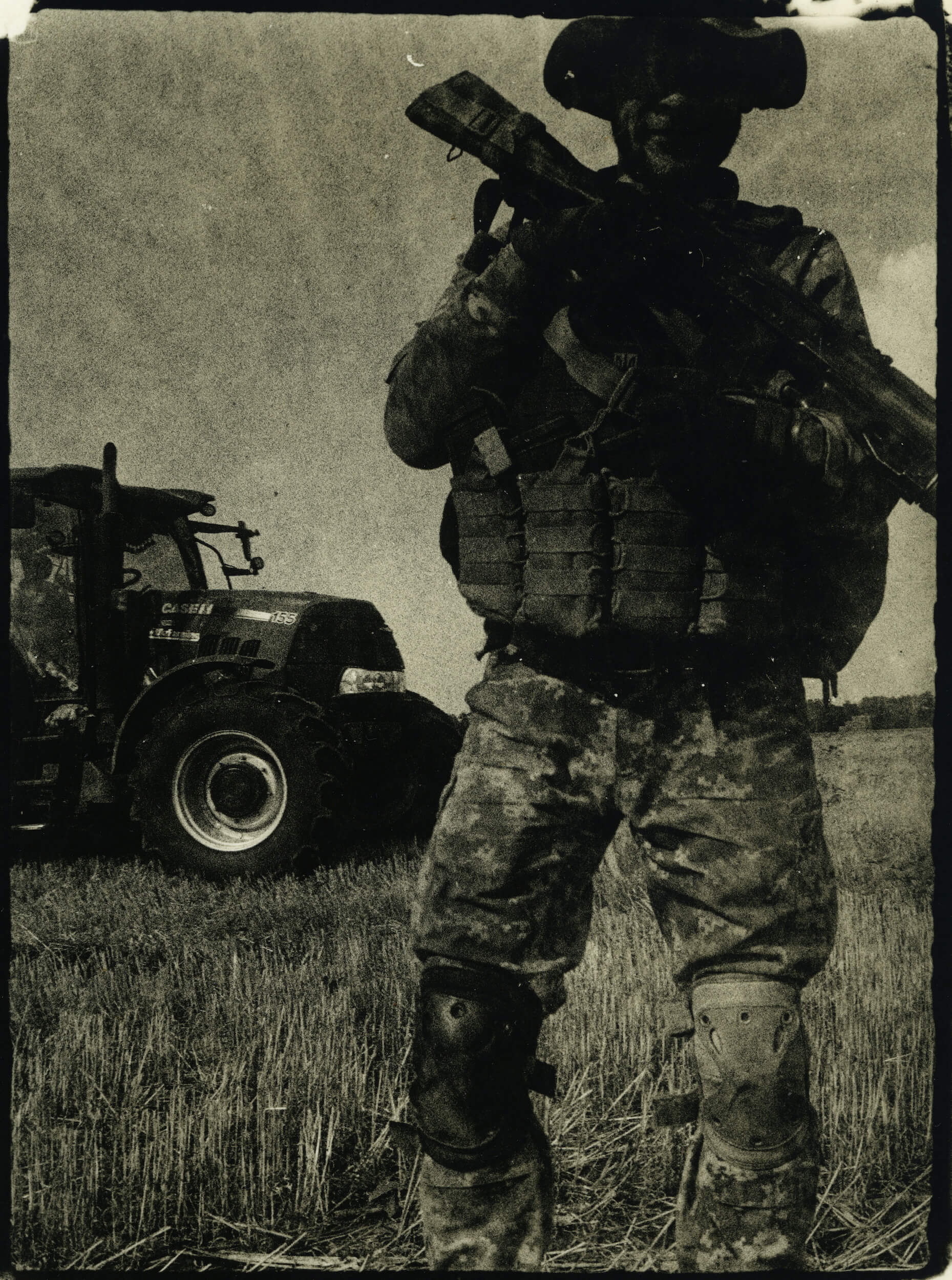

For me, this work is not a separate project. I just document what happens around me. I started by making baby steps: I photographed the city, captured the aftermath of shelling. When I felt that I took enough photos of the ruins, I moved to another “niche” — servicemen and their stories. I realized that war documentation should be divided into smaller chunks, which eventually would add up and compose a big picture. It’s hard to gather all the puzzle pieces together, because I don’t have access to certain topics. But so far I already have one layer of history captured on film and in pictures.

I met a couple of servicemen, we became friends. After several trips that we took together they understood that it was not a random photography project for me, that I wanted to tell their stories. They used to call or text me: “We’re moving now. Pack your things”. Of course, there are some limitations to photographers’ work due to safety rules. For instance, we are not allowed to photograph servicemen’s faces while the war is in its active phase.

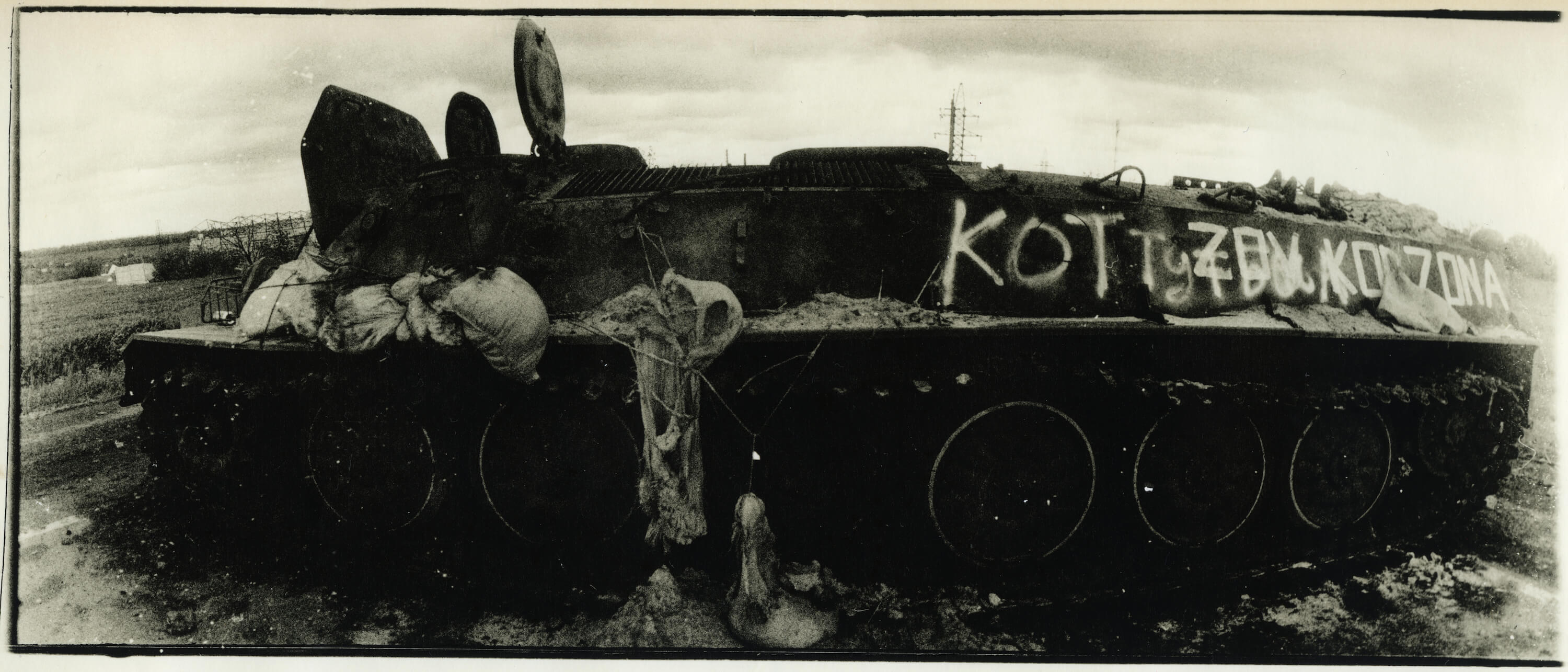

Recently, I wanted to go to the military hospital in Pervomaysk to visit the boys. Their position had been shelled, there were a lot of shrapnel injuries. I wanted to bring them their photographs, but I missed out because of the day-long curfew. I was also told recently that taking pictures of military equipment was prohibited from now on. That’s too bad, because it was a part of my project. At the same time, the Western press is somehow allowed to take those photos. Seeing that foreign reporters have access to some locations that are closed for me makes me jealous. Although their photos as such don’t evoke the same feeling. For us, for Ukrainians, it’s hard to write this story, both mentally, and physically. But I guess it should go how it goes. Step by step, you explore new places, try to get somewhere, and stumble upon good stories from time to time.

I’m very interested in volunteers’ work. Those guys I know, they are crazy. We were in Pryvillia, Lysychansk, Severodonetsk. In Severodonetsk, there was fighting already on the outskirts of the city, but volunteers still brought cat food there. I mean, the city is under fire, there are street fights, locals are freaking out, and people are bringing pet food.

In Severodonetsk, there was fighting already on the outskirts of the city, but volunteers still brought cat food there.

I remember thinking back then: “If our car breaks, we are f*cked”. Roads were filled with crashed cars, there were tons of debris. If you puncture your wheel, you’ll have to grab your camera and go by foot down the Bahmut — Lysyschansk road. And no one knows, whether you will make it or not. I’m not a professional photographer, so I’m very bad at all those logistics issues: I don’t know whom to call and how to solve certain problems. I’m not doing this for an agency, I’m doing this for myself and it’s harder.

But the hardest part is to meet new people and get attached to them only to find out later that some of them got killed in action. There is one photo that has a special meaning to me. Two servicemen walk down a road in Mala Rohan that was recently liberated. The one on the left is named Sasha. I met him a couple of times under different circumstances. And then I documented his funeral. This is a precious photo for me, because Sasha is still alive there. But then I have a photo where people shoot in the air at his funeral. His comrades asked me to publish his last photo, which was taken near Kharkiv. When things like this happen, you learn to look at them from a philosophical standpoint.

The hardest part is to meet new people and get attached to them only to find out later that some of them got killed in action.

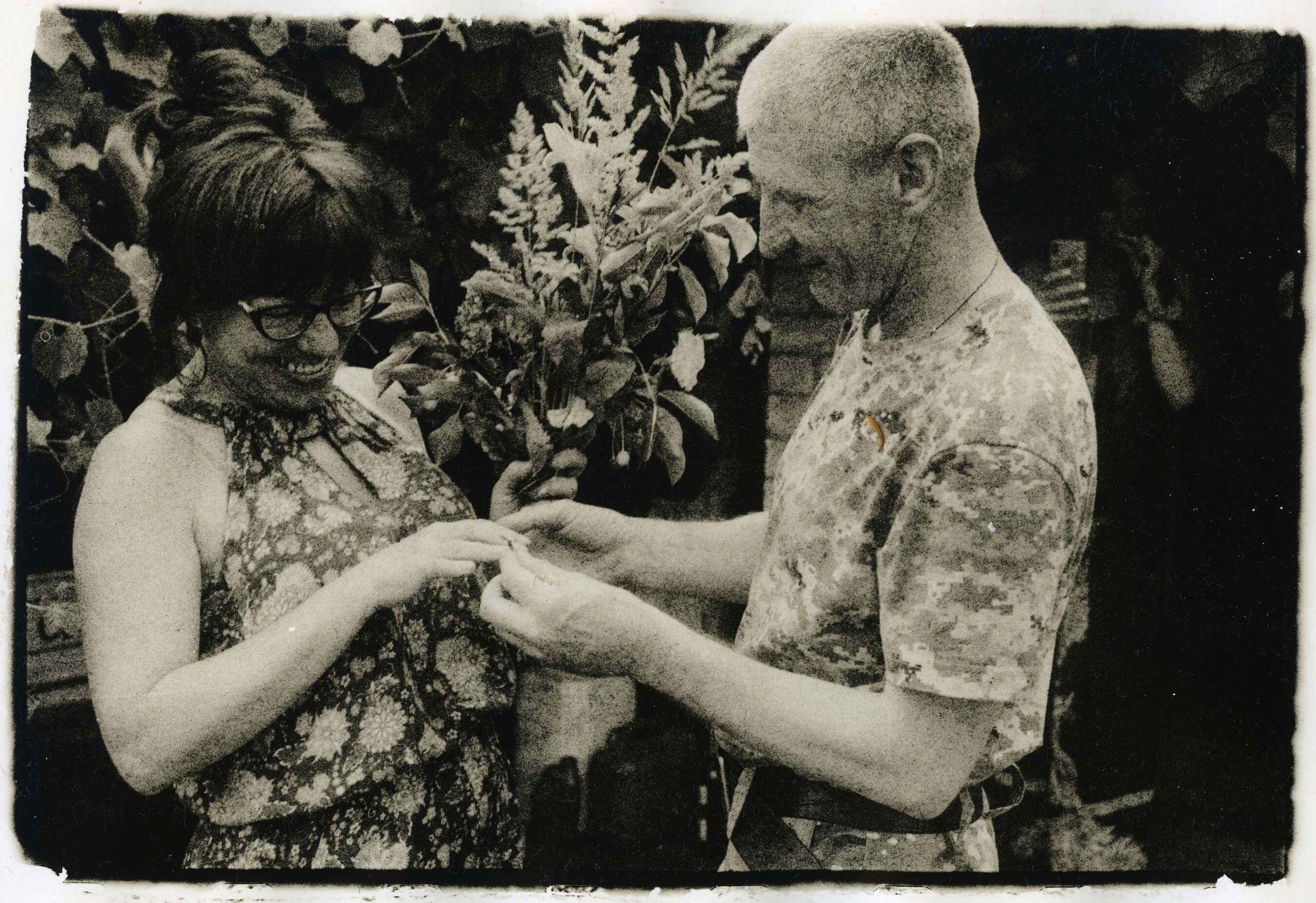

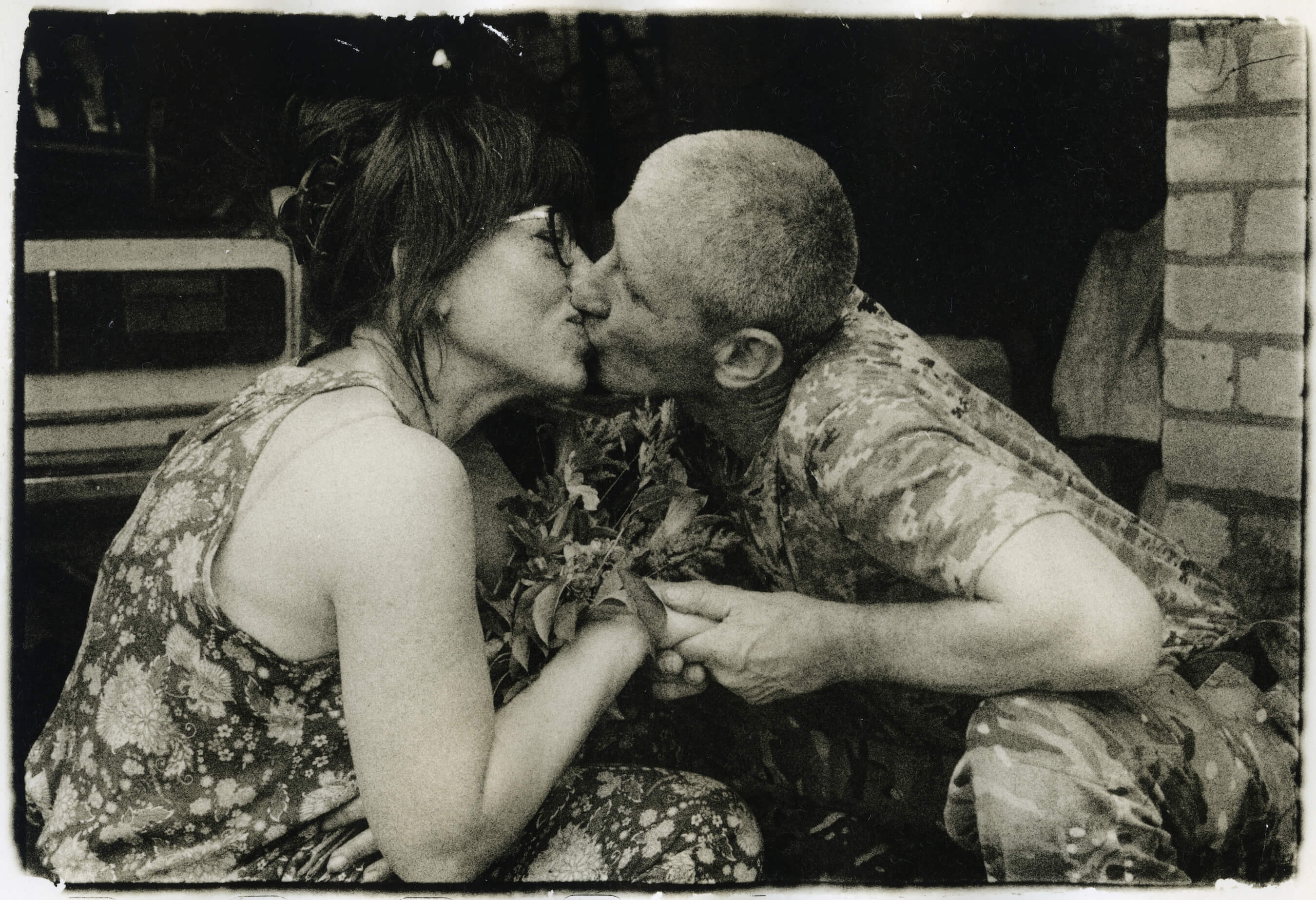

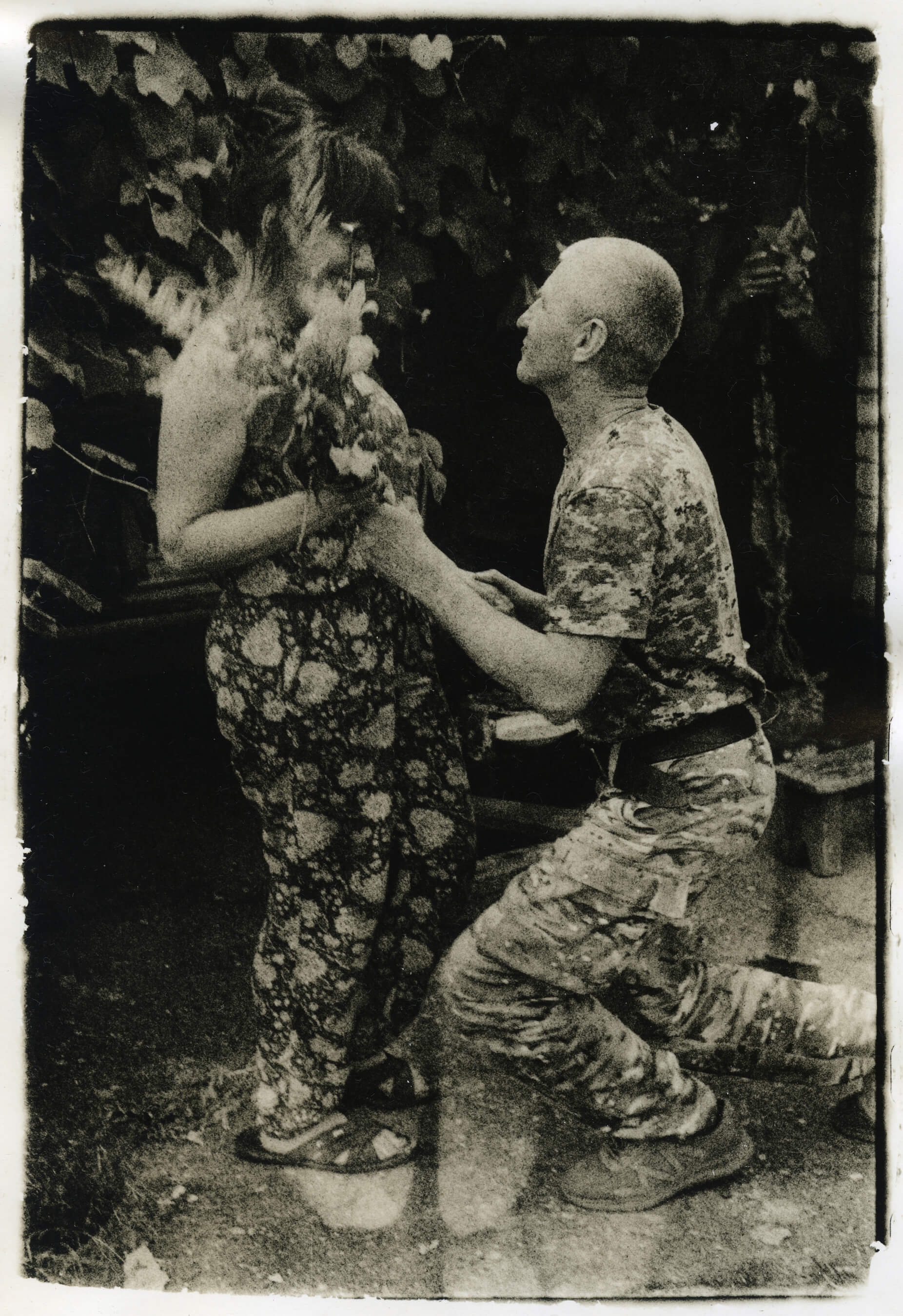

Here is another story. I met servicemen near Sloviansk —they caught up with our group of volunteers. One of the servicemen proposed to a woman-volunteer right in front of my eyes. He made a ring out of a piece of wire and gave it to her. Then they came to Kharkiv and invited me to their wedding in a cafe. I filmed it. Later, they visited me in my

One of the servicemen proposed to a woman-volunteer right in front of my eyes.

House-Museum of Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

All of my photos are black and white. I haven’t even taken a single video on the phone. I try to keep these things away from my phone. Yet, when you shoot on film you can get yourself in trouble with the police or territorial defense. It’s because they know that you’ve taken some photos, but they can’t see them until you develop them. Of course, you can pull out the film and expose it, but that’s not an option, so servicemen have to wait for the pictures. I develop them, go back and give them as gifts if I have a chance.

When you shoot on film you can get yourself in trouble with the police or territorial defense. It’s because they know that you’ve taken some photos, but they can’t see them until you develop them.

The typical routine is as follows: you come home, develop photos, pick up pictures, and print them. Then you take some rest and go through the pictures once again to pick those, which you missed during the first round. I have given 150 photographs to the

Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography

Serhiy Lebedynskyi, director of the MOKSOP museum

New and best