Lesson in Biology: Why Architecture Mimics Nature

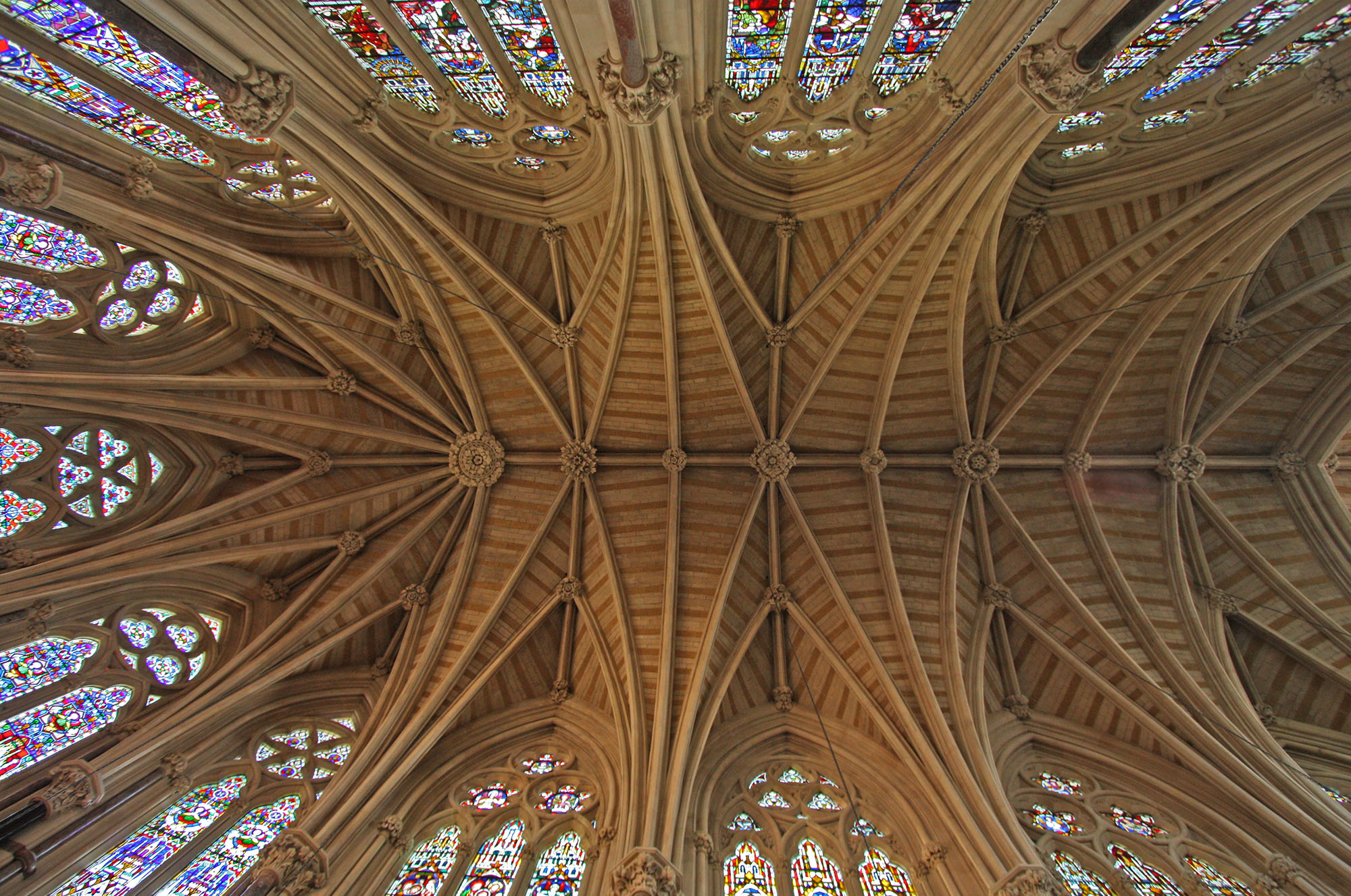

People have long imitated nature in their construction practices. Ancient settlements mimic the nests of birds and insects. Greek columns, like tree trunks, narrow towards the top, and fluting – vertical grooves – imitate plant stems and make columns stronger. The ribs of Gothic temples – the ribs on the vault – perform the same function as the veins of leaves.

The chapel of Exeter College, Exeter, UK. Photo: Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P. / Flickr

Nature outlines are most often used for decoration. Thus, capitals – the upper parts of the column – resemble flowers, and ornaments on surfaces, forged railings and fences repeat the twists of plants. In modern architecture, which peaked between 1893 and 1912, microstructures were often depicted, including ornaments in the form of a cellular structure. This is related to discoveries in biology.

With the advent of reinforced concrete, it became easier to create complex yet economical forms. So architects could borrow entire structures from nature. In the 1960s, a new direction in architectural bionics emerged, based on the imitation of the principles of living nature in design and construction. For example, tissues of living organisms – membranes, flexible fibers – in a stretched form can withstand more stress than a rigid structure. Architects decided that they too could use lightweight elastic materials – and thus cable-stayed roofs appeared.

Palace of Labour in Turin, Italy. Designed by Pier Luigi Nervi. Each column supports a cantilevered slab. Photo by kamikazekaze / Flickr

Incorporating Nature: Plants in Architecture

Architecture often imitates curved plant forms such as leaves, petals, and seed pods. They are well-suited for large-span roofs (without additional supports) because they are lightweight and have good bending properties.

In his projects, Pier Luigi Nervi used the scheme of the leaf of the Victoria regia plant. Following the pattern of the flower, he reinforced thin coverings with a system of sickle-shaped ribs in the buildings of the Gatti factory in Rome, the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Bologna, and the main hall of the Turin Exhibition.

The main hall of the Turin Exhibition, Italy. Designed by Pier Luigi Nervi. The ribbed structure is designed according to the structure of the Victoria regia leaf. Photo: Eahn Turin2014 / Flickr

The structure of the roof of the Centre for New Industries and Technologies in Paris is similar to the venation structure of a fern.

New Industries and Technologies Center in Paris. Designed by Robert Camelot, Jean de Mailly, Bernard Louis Zerfuss, with consultation from Pier Luigi Nervi. Photo by Pierre Metivier / Flickr

The leaves attached to the stem without a petiole are essentially strong cantilever plates. Frank Lloyd Wright borrowed this form when creating the office of the Johnson Wax headquarters. The working room has no internal walls, its ceiling is formed by “water lilies”, the round tops of which are held by thin white columns, and light enters the room through their gaps.

Johnson Wax headquarters in Racine, USA. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith / Wikimedia Commons

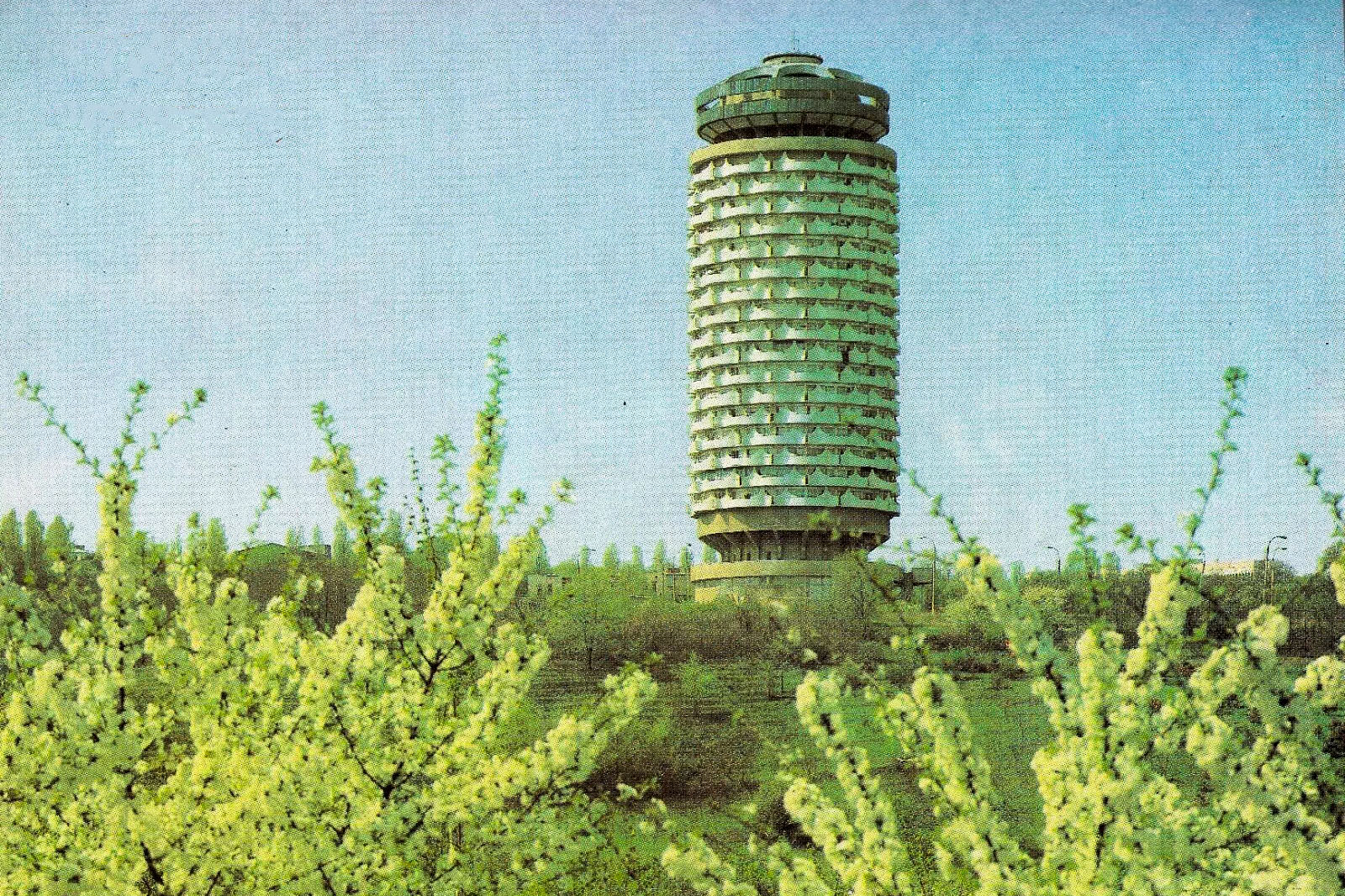

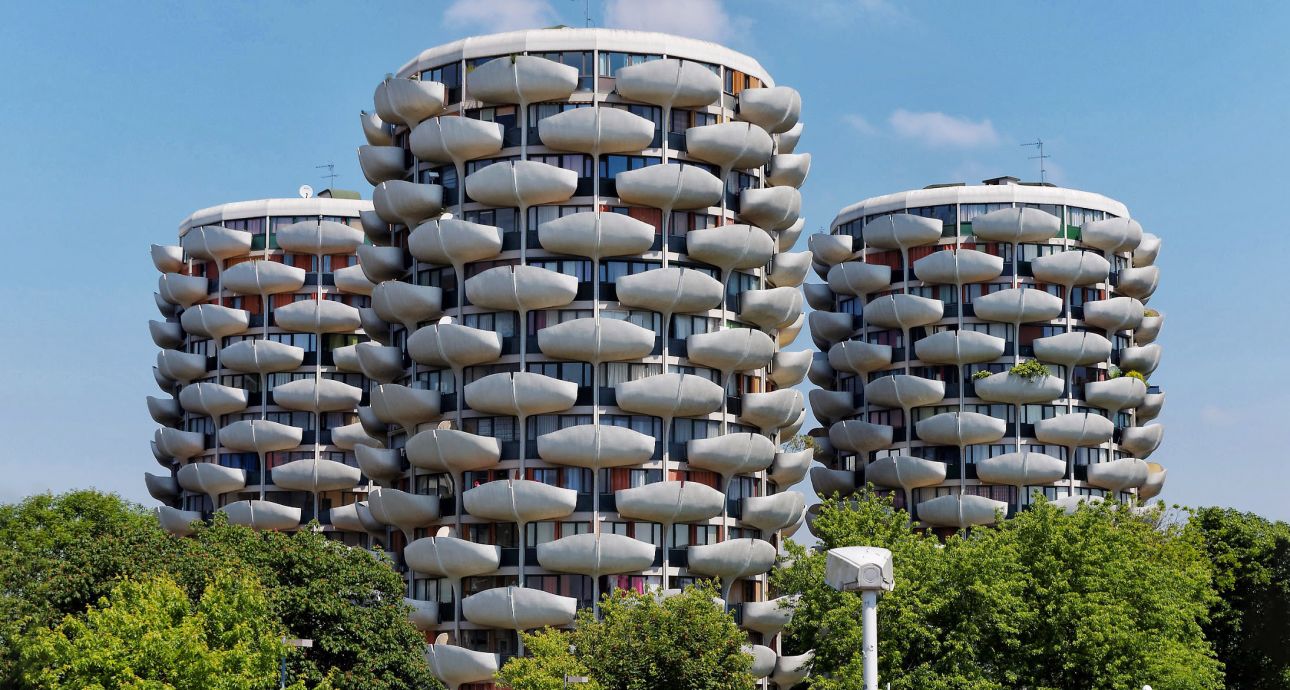

Sometimes plant motifs are used not only for the construction of individual elements but as the basis for an entire building. For example, the houses in the “Choux de Créteil” neighborhood on the outskirts of Paris look like corn cobs. The neighborhood got its name because the balconies of these buildings resemble cabbage leaves. The houses in the Obolon district of Kyiv, the Kukurydze building in Katowice, the “Chamomile” house in Chisinau, and the demolished Youth House in Yerevan are all referred to as “corn houses”.

In architecture, principles of self-regulation of living nature are also applied. Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjaković designed a villa in the shape of a lamella flower, whose “petals” rise and fall depending on the degree of solar radiation.

In the USA, Santiago Calatrava designed the winged building of the Quadracci Pavilion at the Milwaukee Art Museum. This is not only bionics but also kinetic architecture: huge wings weighing 110 tons hover over the complex, plastic building, which move depending on the weather conditions. The museum “flaps” its wings several times a day, creating a comfortable microclimate inside – shading or, on the contrary, opening up a bright interior space.

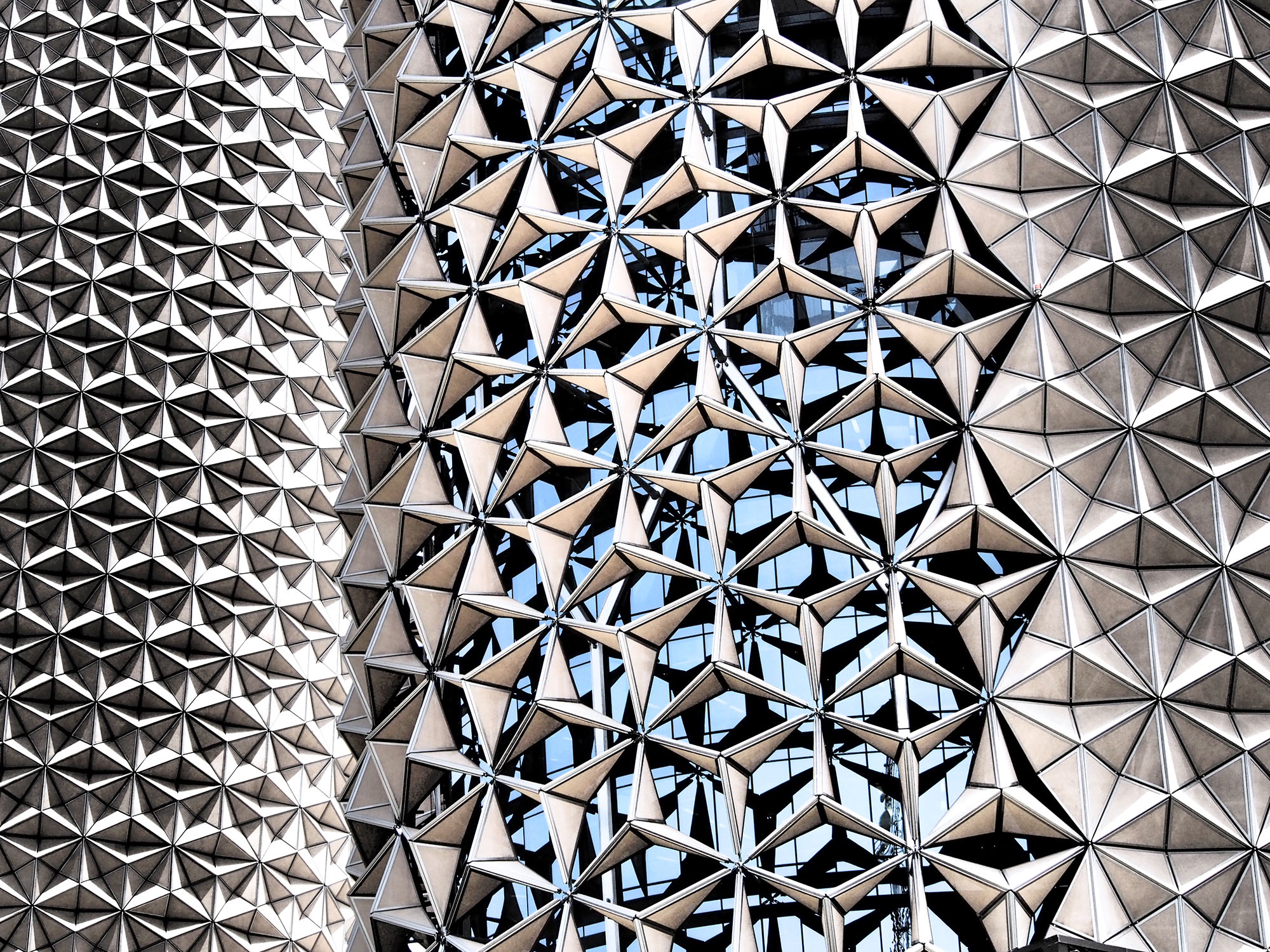

Another example is the Al Bahar Tower skyscraper in Abu Dhabi with a dynamic facade consisting of a series of moving elements. These elements, called mashrabiya, protect the interior of the building from the burning sun of the desert while allowing natural light and air circulation. The mashrabiya is controlled by a computerized system that is oriented towards weather conditions and the position of the sun.

Facade of Al Bahar Tower skyscraper in Abu Dhabi. Designed by Aedas Architects. Photo by iTimbo61 / Flickr

Plants that grow in water or in a climate with increased humidity have more air cavities in their stems and leaves to improve air exchange. This is mimicked in “breathing” walls – they have numerous holes through which air quickly flows into the room.

The placement of buildings is also influenced by natural principles. In lettuce, the flat, flattened leaves are directed towards the south edge, towards the highest level of solar radiation. If the flat side of the leaves were facing the sun, it would kill the plant. Buildings in hot climates are also constructed in the form of plates, with their narrow ends facing south. An example of this is the Pirelli building in Milan.

Trees that grow in windy areas – beeches, spruces, firs – are more squat and have a conical shape. Czech architects were inspired by this when creating a television tower on Mount Jeshted, where wind speeds reach 80 meters per second. As a result, the structure has a massive wide base and is very different from traditional towers, but is able to withstand strong winds.

The Jested Tower in Liberec, Czech Republic. Designed by Karel Hubacek. Photo: Stanislav Dusik / Wikimedia Commons

The marine world in architecture

In the project of the Museum of Modern Art in Niterói, Brazil, Oscar Niemeyer embodied the principle of growth of a shell. The building was located on a small plot on the shore of Guanabara Bay. Niemeyer created a smooth curved structure and elevated it above the ground. This was intended to create the impression of “continuous growth”, like in a shell that expands with each spiral.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói, Brazil. Designed by Oscar Niemeyer. Photo: Rodrigo Soldon / Flickr

In nature, the structure of shells is very common – smooth shells of mollusks, the carapaces of crustaceans, the shells of eggs, the ribless petals of flowers, even the human skull. Thin shells, due to their curvature, are able to withstand significant loads and cover a larger area than any flat surface. The fragility of a scallop shell or a crustacean’s “armor” is compensated for by the convexity of their shape, so they are not damaged by the weight of the surrounding water. Monolithic shells constructed according to this principle are found in the Sydney Opera House, the Lotus Temple in New Delhi, and the building of the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technical Expertise and Information in Kiev, known as the “UFO” on “Lybidska”.

Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technical Expertise and Information in Kiev, Ukraine. The structure of the building is based on the shape of a bivalve shell. Designed by Florian Yuryev and Lev Novikov. Photo by Valentyn Dedyov, archive of Elmira Ettinger

Mollusks with wavy shells can live deeper because they can withstand even more weight of water. Therefore, instead of smooth shells, architects use wavy or folded structures to create a more rigid construction. The amount of material and weight of the structure do not increase. According to Spanish engineer Eduardo Torroja, the best structure is one whose reliability is primarily ensured by its shape, not by the strength of its material. The latter is achieved easily, while the former is achieved with great difficulty.

Felix Candela used a wavy form in the projects of Los Manantiales and L’Oceanografic restaurants. Despite their delicate appearance, the structures of these establishments are strong and

The lightweight concrete surface of the Los Manantiales restaurant has withstood several devastating earthquakes.

Oceanographic Park Restaurant in Valencia, Spain. Designed by Felix Candela. Photo by Felipe Gabaldón / Wikimedia Commons

Natural bubbles served as a prototype for geodesic domes – isolated structures with a closed ecological system. The Eden project, implemented in the UK by Nicholas Grimshaw in 2001, is a good example of a geodesic dome. It houses the world’s largest greenhouse, in which three different climates are maintained: tropical, Mediterranean, and typical moderate for the country.

Project Eden by Nicholas Grimshaw in Cornwall, United Kingdom. Photo: Matt Brown / Flickr

The National Library of Kosovo’s skylights were designed in the form of bioclimatic domes by Andrija Mutnjaković. In this case, the convexity allows for a soft dispersion of the incoming sunlight.

National Library of Kosovo in Pristina. Designed by Andrija Mutnjaković. Photo by Arben Llapashtica / Wikimedia Commons

Architecture inspired by animal kingdom

Soft tissues in the body, such as the elastic membranes of the diaphragm, skin, tendons, muscles, and membranes, typically work through stretching. Thanks to them, organisms can move and change shape. Similar solutions in nature can be compared to hanging coverings – cable-stayed, tent-like, membrane-based – as well as inflatable structures.

Suspension structures were used by Kenzo Tange for the Olympic complex in Yoyogi in Tokyo and the sports complex in Kagawa. In Ukraine, they can be seen in the projects of cinema-concert halls “Ukraine” in Kharkiv and “Yuvileiny” in Kherson, as well as in the Zhytniy market and the Furniture House in Kyiv.

Yoyogi Olympic Complex in Tokyo. Designed by Kenzo Tange. Photo: Arne Müseler / Wikimedia Commons

Olympic complex in Yoyogi by Kenzo Tange. Photo: Sofía Lens / Flickr

Similar properties are found in spider webs, which have been reflected in architecture through tent-like structures. Our ancestors built housing based on the principle of a tent, and modern examples include the covering over the Olympic Stadium in Munich. Engineer-architect Frei Otto created it by analyzing the structure of dense spider webs. In Ukraine, a circus in Dnipro designed by Pavel Nirinberg has a tent-like roof.

Olympic Stadium in Munich. Project by Frei Otto. Photo by Fred Romero / Flickr

Sometimes buildings literally imitate animals. The design of Kennedy Airport is based on the shape of a butterfly, while the roof of the Palace of Sports in Mexico resembles the shell of a vulture turtle.

Sports Palace in Mexico City. Project by Felix Candela. Photo by Eneas De Troya / Flickr

Exhibition hall in Silesian Park, Chorzów, Poland. Project by Jerzy Gottfried and Władysław Feiferak. Photo by Igor Gorbunov

What could go wrong

Natural forms are familiar to us, so when reproduced in buildings, they usually evoke pleasant emotions. However, only the bionic architecture that has both aesthetics and logical use can be considered successful.

There are two main approaches to working with biological structures. One is a creative approach, where the principles of living structures are studied and applied for the benefit of humans. Good examples of a creative approach are the works of Nervi, Niemeyer, Otto, Saarinen, Sargel, Torroja, where form exists not only for the sake of form. These are also abstract “live” structures by Zaha Hadid and complex bionic structures by Santiago Calatrava.

Translation: David S. Ingalls Rink in New Haven, USA. Designed by Eero Saarinen. Photo by Jussi Toivanen / Flickr

The City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain. Designed by Santiago Calatrava. Photo: Artur Salisz / Flickr

Another way is imitation, mechanical transfer of natural forms into architecture often just for the sake of originality and without considering practicality.

Spanish architect Antonio Gaudi, a bright representative of modernism, used biological structures to make his buildings look more fantastic. He imitated plant forms, bone microstructure, cellular structure, but he reached pure formalism and mystification in this. His architecture creates an almost surrealist contrast between natural forms and the purpose of architecture. A person does not see a logical organization of the structure in front of them, although in nature, which Gaudi imitates, everything is quite logical.

Facade of the Casa Batlló building in Barcelona. Project by Antoni Gaudí. Photo: Francisco Schmidt / Flickr

One of the most unsuccessful examples of copying is the Mriya Resort & SPA hotel in Opolzneve, Crimea, opened in August 2014 and designed by Norman Foster for Sberbank of Russia. The hotel was designed in the shape of a huge metal flower with four petals. The building turned out to be too complex, heavy, unnatural, and

Technicism is an excessive obsession with technology at the expense of structure, appearance, and even the functions of a building.

Mriya Resort & SPA in Opolzneve, Crimea. Designed by Norman Foster. Photo: Mriyaresort / Wikimapia

Another bionic structure ruined by high-tech is the St. Mary Axe skyscraper in London, designed by Foster + Partners. The shape of the building is inspired by the sea sponge Venus Flower Basket. The structure has a differentiated structure – a lattice exoskeleton that disperses water flows. The lattice structure of the building provides passive cooling, heating, ventilation, and lighting. However, the excess of metals and glass, the bulging shape, and spiral-like stripes make the structure quite clumsy. Because of this, it was nicknamed the “cucumber”.

The St. Mary Axe 30 skyscraper in London. A project by Foster + Partners. Photo: d0gwalker / Flickr

Overall, technicism is characteristic of modern bionic architecture, as in nature one can borrow not only forms and structures, but also the ability for self-regulation and transformation. Passive cooling, various movable elements that protect from the sun – all these natural ideas help to embody modern technologies in construction. How successful this will be depends on the materials, the sense of measure of the architect, the idea of proportions and harmony, which nature itself suggests.

Cover photo: Paul Fleury / Wikimedia Commons

New and best