The Birth of Ukraine: Victoria Ivleva’s Photo Project

Russian photographer and journalist. Was born in Leningrad, lives in Moscow. Graduated from the Journalism Department of Moscow State University (MSU). Has worked in many hotspots around the globe, contributes to Russian and foreign publications. Holds the Golden Eye Award from the World Press Photo for a shoot she made in the destroyed reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, as well as a German Gerd Bucerius award, an award from the Russian Journalists’ Union and two Andrei Sakharov Awards.

There was this paragraph from my book ‘The Travel of a Facebook Worm Around Ukraine’:

“Women, picking the frozen ground to get the paving stones out, barricades from bags filled with snow, fires, sticks, middle ages, a three-meter poster saying ‘I see all your deeds, mortal’ with the crazed eyes of a Savior, and human figures moving forward again and again, to pull the wounded people out of reach of the gunfire, ambulance sirens, bitter rubber smell, wicks from white cloth torn to pieces put inside bottles and jars of Molotov cocktails, mysterious snipers, bullet holes in the rusty metal shields stained with blood, a girl volunteer with a wound in her neck, the gray appearance of Berkut special police force officers, gushing blood, black smoked faces, tires, fire, and chaos, chaos, chaos.

And suddenly, in the middle of the chaos — the birth of a nation.”

I wrote this text in 2014. I was wondering how using the language of photography I could portray the feeling of the birth of a nation today. At first it seemed impossible, as the key events — the Maidan protests — have already ended, and photography is always about the here and now.

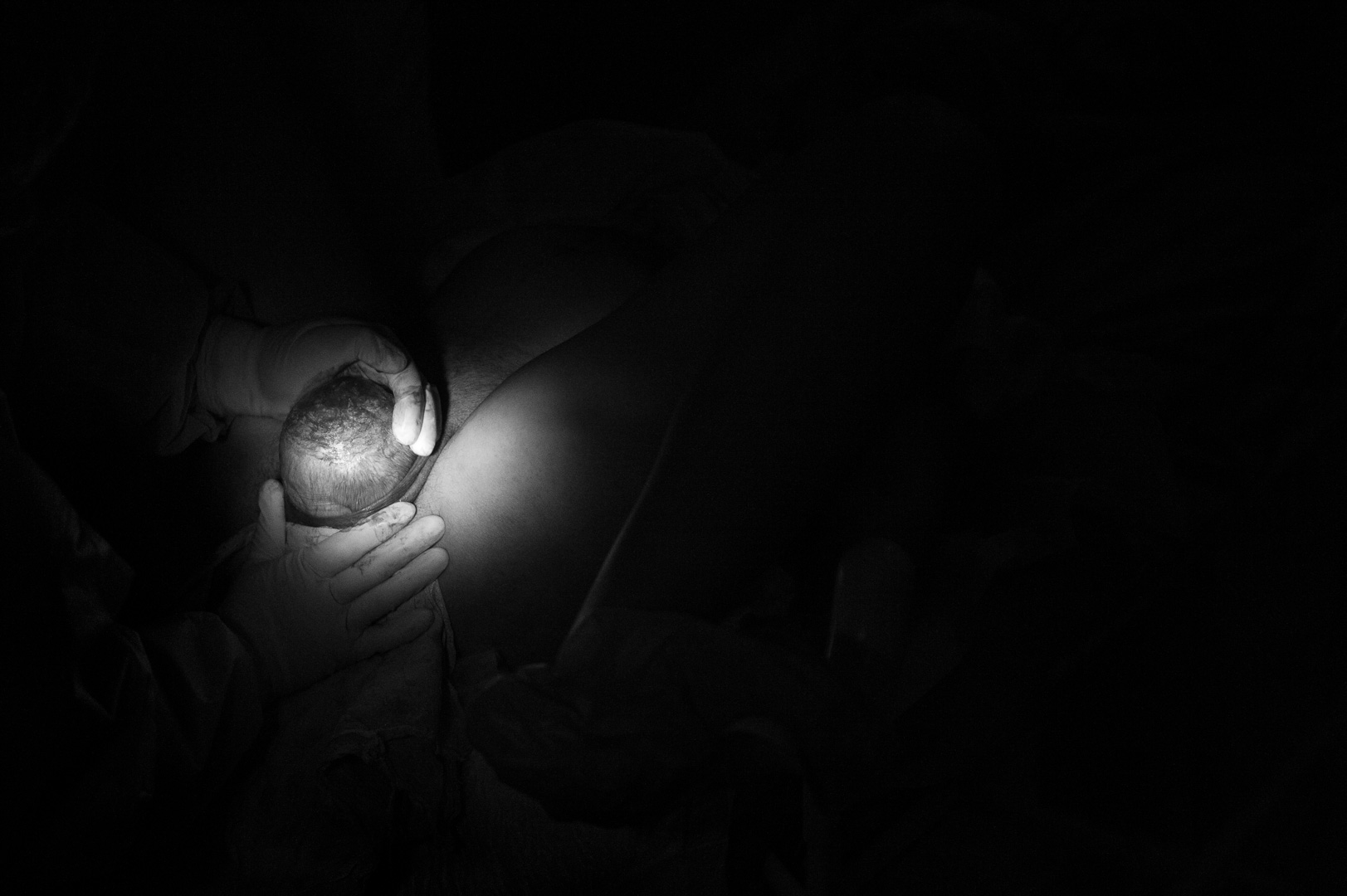

Later, I realized I wanted to travel around Ukraine and photograph real births, which would symbolize the birth of a new nation — through pain, suffering, blood, and sometimes death. This is how the project ‘The Birth of Ukraine’ came into being.

The idea of the project is to present a metaphor of the birth of the new national identity which has been forming in Ukraine after Maidan. The suffering of people because of the war in the eastern part of the country and the annexation of Crimea, and at the same time, a rare uplift and enthusiasm of people from all social strata related to hopes for the independent future of free Ukraine are symbolically reflected in the photographs of birthing mothers and their newly born children.

I worked on this project during two separate periods of time, in March and in May 2016, and it had a ‘one day one city’ structure. I had to spend nights on trains and in maternity wards, and I am very grateful to all on-call doctors for their help. After the last shoot, when it was time to go back to Russia, the chief of the maternity ward in Starobilsk, a city in the Luhansk oblast, took me to the border in his car in the middle of the night and helped me cross it. I had a general impression that people who work in obstetrics in Ukraine are incredibly pleasant and nice. It may be the outburst of positive energy that happens when a child is born, which impacts those who observe childbirth all the time — or I was just incredibly lucky in almost all the maternity wards.

It must have been the first shoot in my life when I could not interfere at all — you can’t increase the suffering and pain for a good photo and you can’t keep a newborn human in the cold only because I want to take another picture. Several times they put me in an interesting shooting location and asked me not to move, because there were sterile instruments to the left and to the right of me. I didn’t move and stood there with my camera aimed, and then at the most important moment someone’s back in a white medical gown would step in front of me, and I lost a photograph.

This was the first shoot when I required fluorography [to check for TB] — this was the requirement of the Ukrainian Ministry of Health, and I couldn’t have implemented this project without their permission.

I was very scared that I’d fail only because nobody would agree to be photographed. But this didn’t happen — and 34 beautiful future mothers participated in my project.

It was one of the happiest shoots of my life. It filled me with light, joy, and hope.

I see this project as a gift to Ukraine, and as another opportunity to talk about this gentle and incredible country, about the price of life and death, about freedom and human purpose.

Having said it all, I don’t feel that it makes my personal guilt and my personal responsibility for the war, the killed, the destitute, the displaced, the suffering, the unhappy people. I did too little to stop the war. And I will have to live with this knowledge till the end of my days.

P.S.

I have posted separate photographs from my project on my Facebook page, and for some reason it has attracted the incredible attention of the puritan or even antiphotographic and scary forces. People, who left me under the impression they have never been born themselves, have not given birth or at least participated in conception, have gotten very experienced complaining on Facebook. First, I was banned for a week for this photograph that Bird In Flight and I have now taken precautions and covered with a kind of movable curtain.

I am a very teachable person, so in the next picture I covered a woman’s nipple with a black Malevich square.

Malevich didn’t help, and I was banned for another month. Suprematism proved futile against bigotry.

Is it time to start a larger professional conversation about it? Not about those who complain — all is clear about them, but about those who can’t tell porn from documentary photography, but are in the position to make decisions that look like the Middle Ages.