On the Outskirts: Poland Before the European Union

Poland spoke about wanting to join the EU since the early 1990s. It took ten years to do it — Poland got its long-awaited membership in 2004.

There was a price to pay for economic growth and open borders: millions of Polish professionals emigrated to richer countries in Europe.

Currently, Poland has a strained relationship with the EU. In 2018, the president of the country, Andrzej Duda, signed a law which prohibits accusing Poland of collaborating with the Nazis during WWII, and European politicians started talking about a freedom of speech violation. The country risks losing its European subsidies.

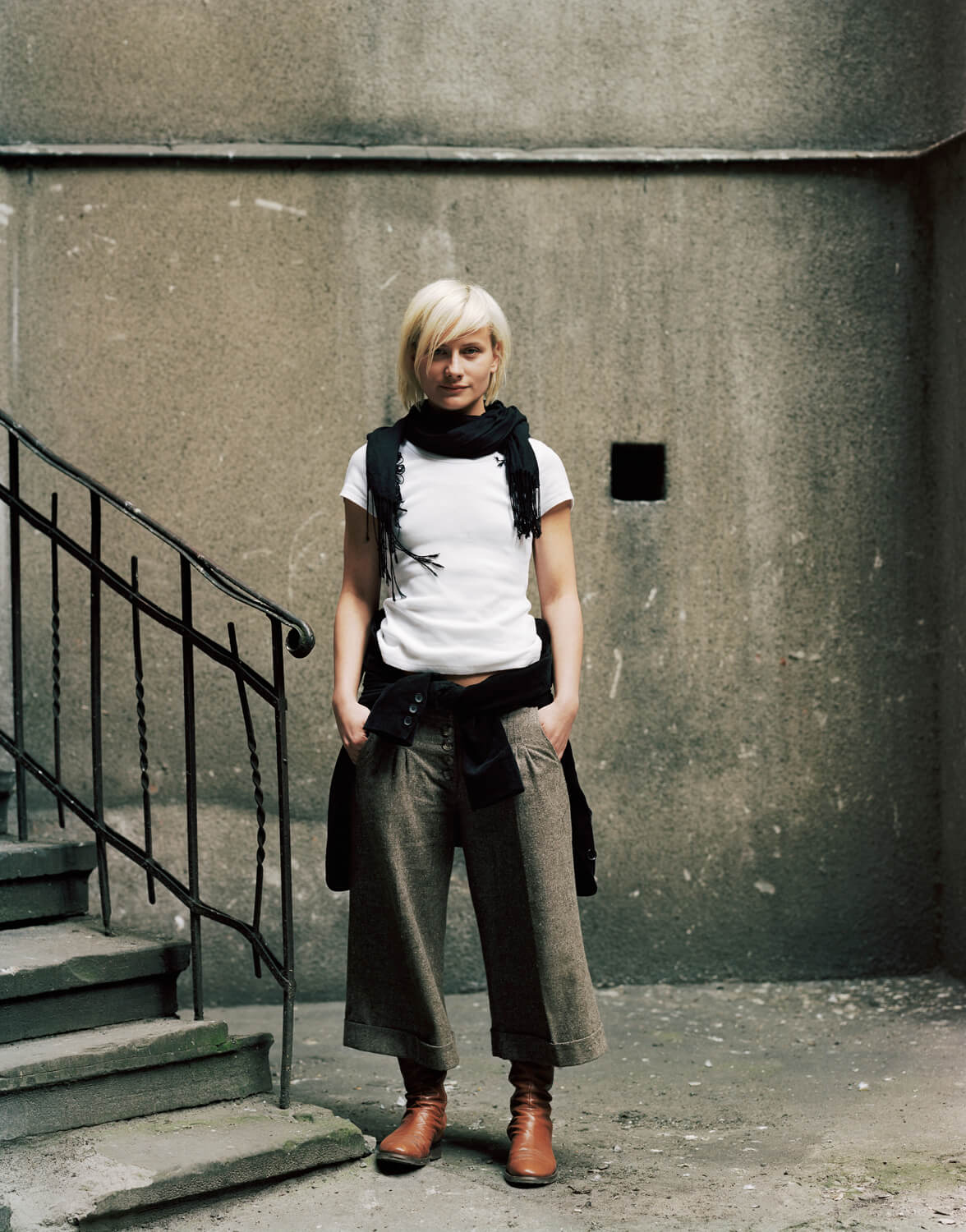

British photographer Mark Power traveled to Poland immediately after it entered the EU. In his photographs there are provincial cities and landscapes of a country that just became a part of Europe.

British documentary photographer, member of Magnum Photos agency.

— Until 2004, almost all my work had been made in the UK. I’d always believed that artists made their best work in a place that was familiar to them, a place they understood. I expected to spend a month in Poland making new work, and I didn’t yet know about what.

I had been there twice before, in 1989 and 1990, but Poland was a country I hardly knew. When I first arrived in Warsaw in September 2004, right at the beginning of the original Eurovision’s project, I stood at the window of my rented apartment on the 14th floor of a tower block, looked over the city, and wondered what on earth I was going to do.

Polish photography, at the time, was quite repressed, stuck somewhere in the 1970s. The only photobooks that seemed to exist were either about the Holocaust or, otherwise, albums of pretty mountains, lakes and castles shot in glorious sunshine and against blue skies. This was not the Poland I was seeing from a car window.

I called Magnum in Paris and asked if they could help me find a Polish assistant. The following day I met Konrad Pustoła, who would, in future years, grow to become one of Poland’s most important artists. Konrad became my sounding board, my guide, my translator, my driver, and my friend. He taught me to understand that, as a foreigner, I might after all have something interesting to say about his country.

After the initial one-month commission I delivered my work to Magnum, but also made the decision to continue to work in Poland. I worked with Konrad for the next three years, before he left Poland to study postgraduate photography at the Royal College of Art in London, the first Pole ever to do so. After he moved to the UK, I had the confidence to continue to work in Poland alone, which I did for a further two years.

We have to remember that Poland is stuck between Germany and Russia, not exactly the safest place to be. Any changes were very slow at first. I think it was because of this that older generations had little trust in this newfound freedom, and the opportunities that came with it.

The young people are the ones driving around in the expensive cars today.

Kraków, which I still visit often, has become very gentrified. These days it’s very clear that Poland has changed almost beyond recognition, particularly in the cities. But back in the noughties changes were primarily happening inside people’s heads.

Although the current incumbent, right-wing government is no supporter of the EU. But ask the ordinary person on the street and most would agree that Poland has changed for the better since 2004.

I love the space in Poland, the opportunities, and the people, but most of all I love working there as a photographer. It reminds me of the UK in the 80s. In the UK, attitudes towards photography have changed so much, and working in the street is very difficult. It’s much easier to work in Poland and, to me, it sits somewhere between the familiar and the exotic… it’s the perfect place to be.