Last Words: What People Wrote on the Walls of an NKVD Prison in Germany

A stern gray building stands away from the tourist routes around German Potsdam. Since the end of WWII and until the 1980s, it housed the main remand prison of the Soviet secret services in East Germany. The building on 1 Leistikow Strasse was a part of the military town, enclosed by a barbed wire fence.

Age Is No Obstacle

Right after the war ended, Soviet counterintelligence was hunting down Nazi war criminals — real or imaginary. The youngest of them was 12 years old. Later, the Chekists refocused on searching for spies and saboteurs who wanted to undermine the sovietization of East Germany.

For instance, in 1946 two Germans aged 15 and 16 ended up in prison for skipping the obligatory Russian classes. Two other friends of these guys were already behind bars — one of them for possessing an illegal gun. Finally, all four of them were sentenced to death. One of the boys was pardoned, and the death sentence was replaced with a lengthy term in labor camps. Others were shot.

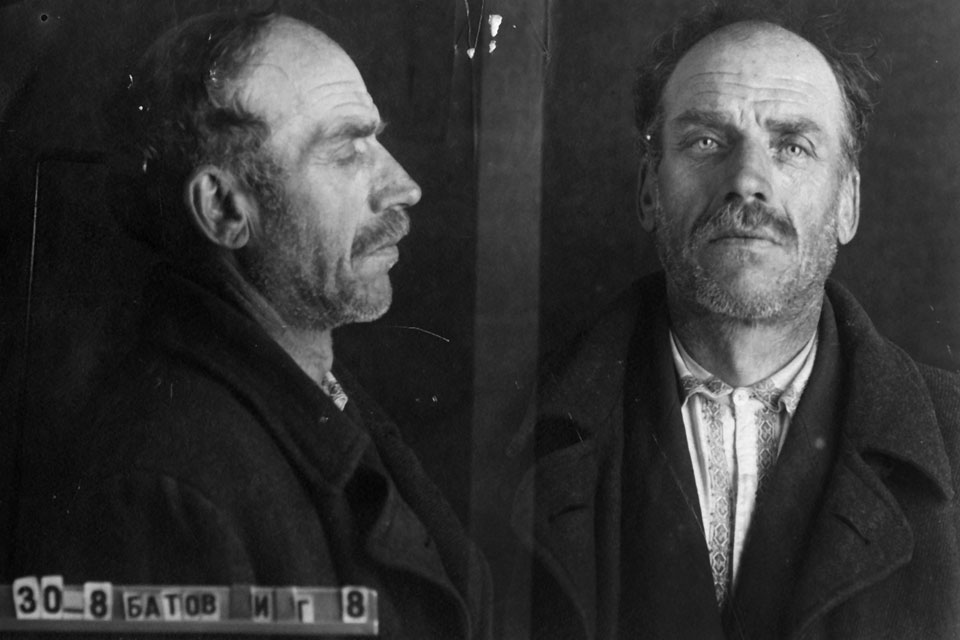

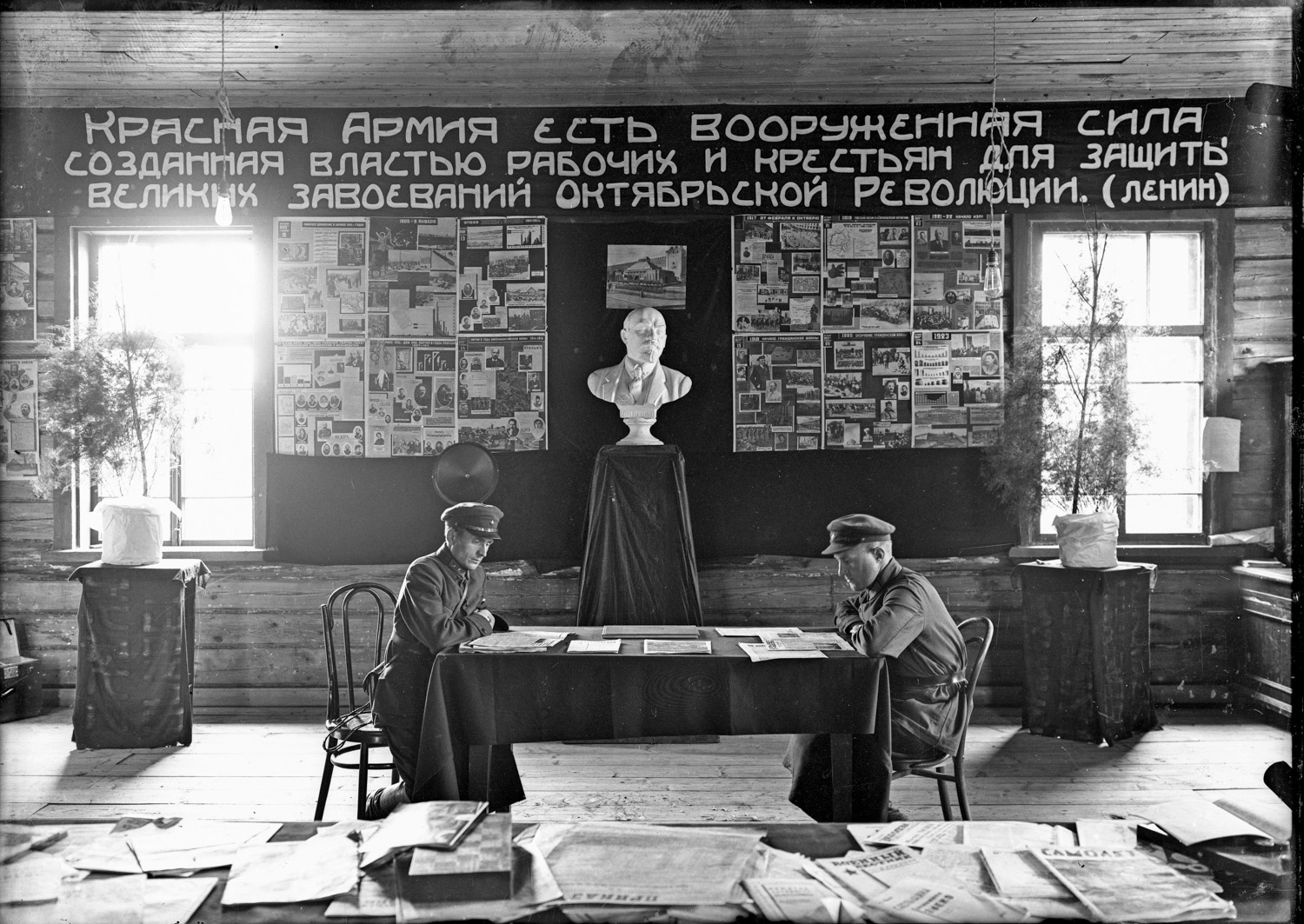

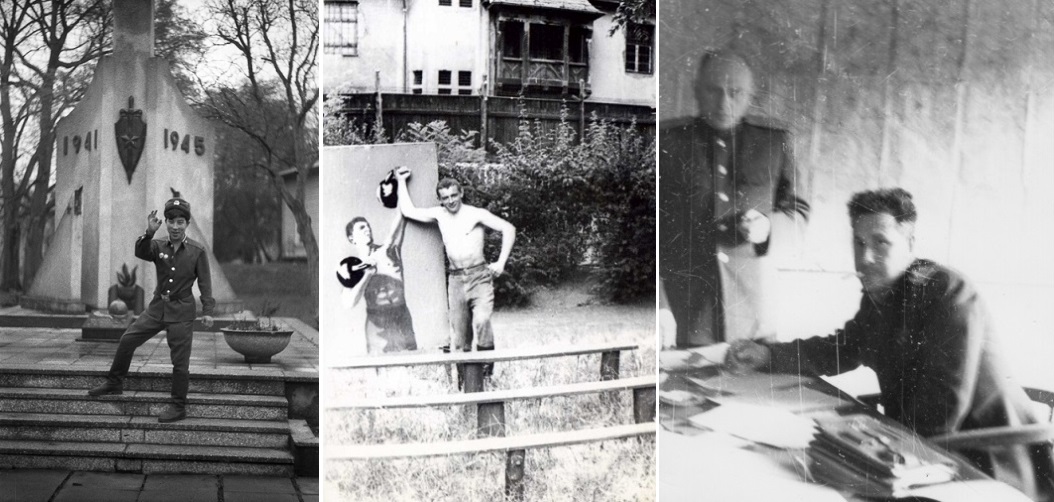

Employees of the prison in Leistikow Strasse. Photo: Potsdam-Museum; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington

You Can’t Put Fresh Paint on Everything

In 1955, after an agreement between the USSR and the GDR, the profile of the prison changed. Germans were no longer detained there, as their cases were forwarded to the Stasi, GDR’s Ministry for State Security. The prison in Potsdam now processed Soviet citizens: there was about 0.5 million of them in Potsdam. They were conscripts, officers, and civil public officials. They were detained on charges of political crimes and criminal offenses: attempt to run away to West Berlin, theft, murder, or going AWOL.

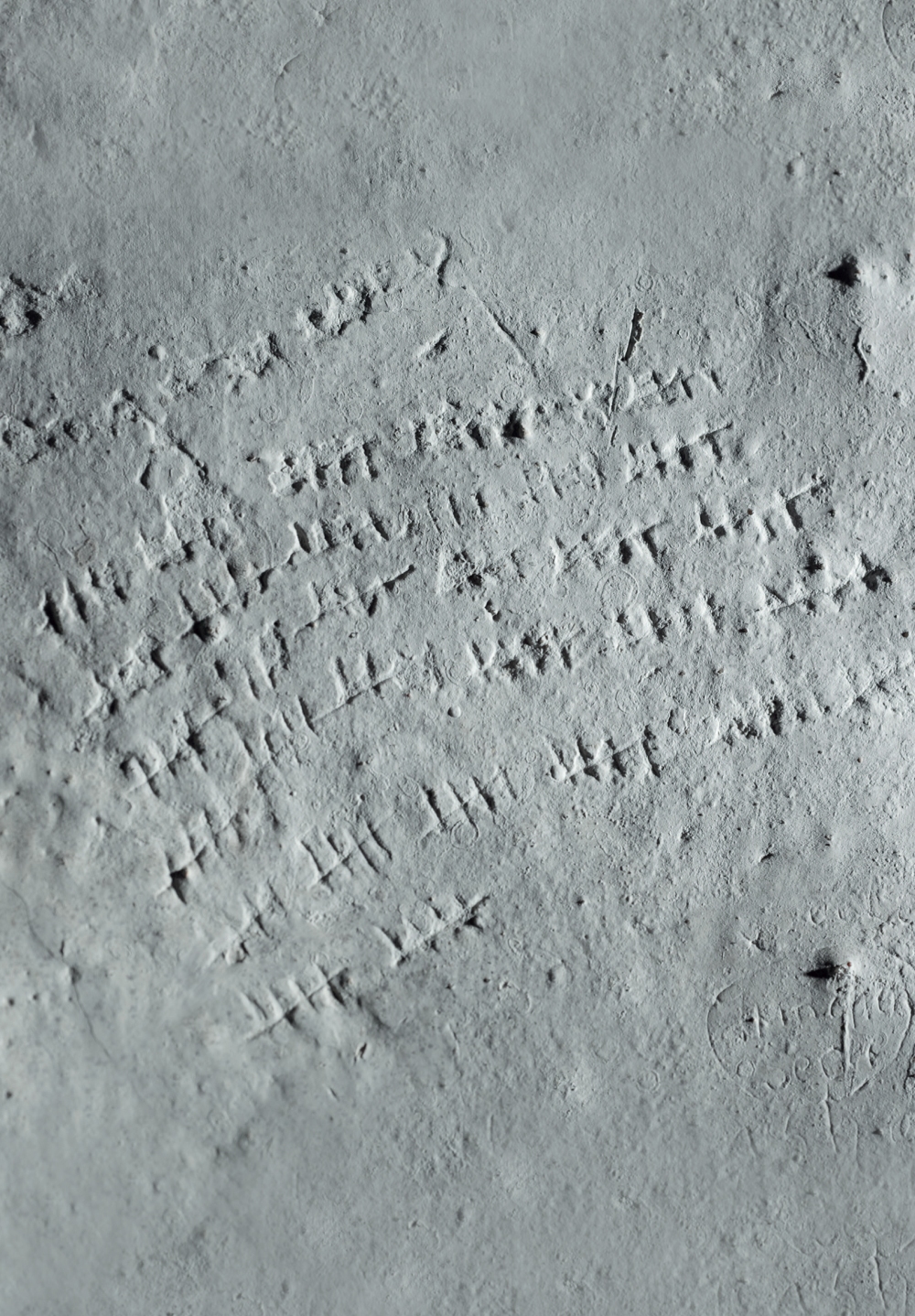

“Sentenced according to Article 58.” Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic covered a wide range of political crimes — from counterrevolutionary sabotage to treason. Execution by shooting was an allowed punishment in 13 of the 14 paragraphs of Article 58.

“Cosy was / A room where we used to live / We parted in a foreign land / I was taken somewhere / Farewell, my family, wait for me and I shall come / My time will come / I’ll find your easy-to-notice house / By the wide road”

Although the prison administration battled graffiti and covered the walls of cells with fresh paint from time to time, numerous inscriptions are still visible on them. Prisoners scratched their names and addresses, wrote about their sentences, talked to their family and loved ones. Over half of the messages are in Russian.

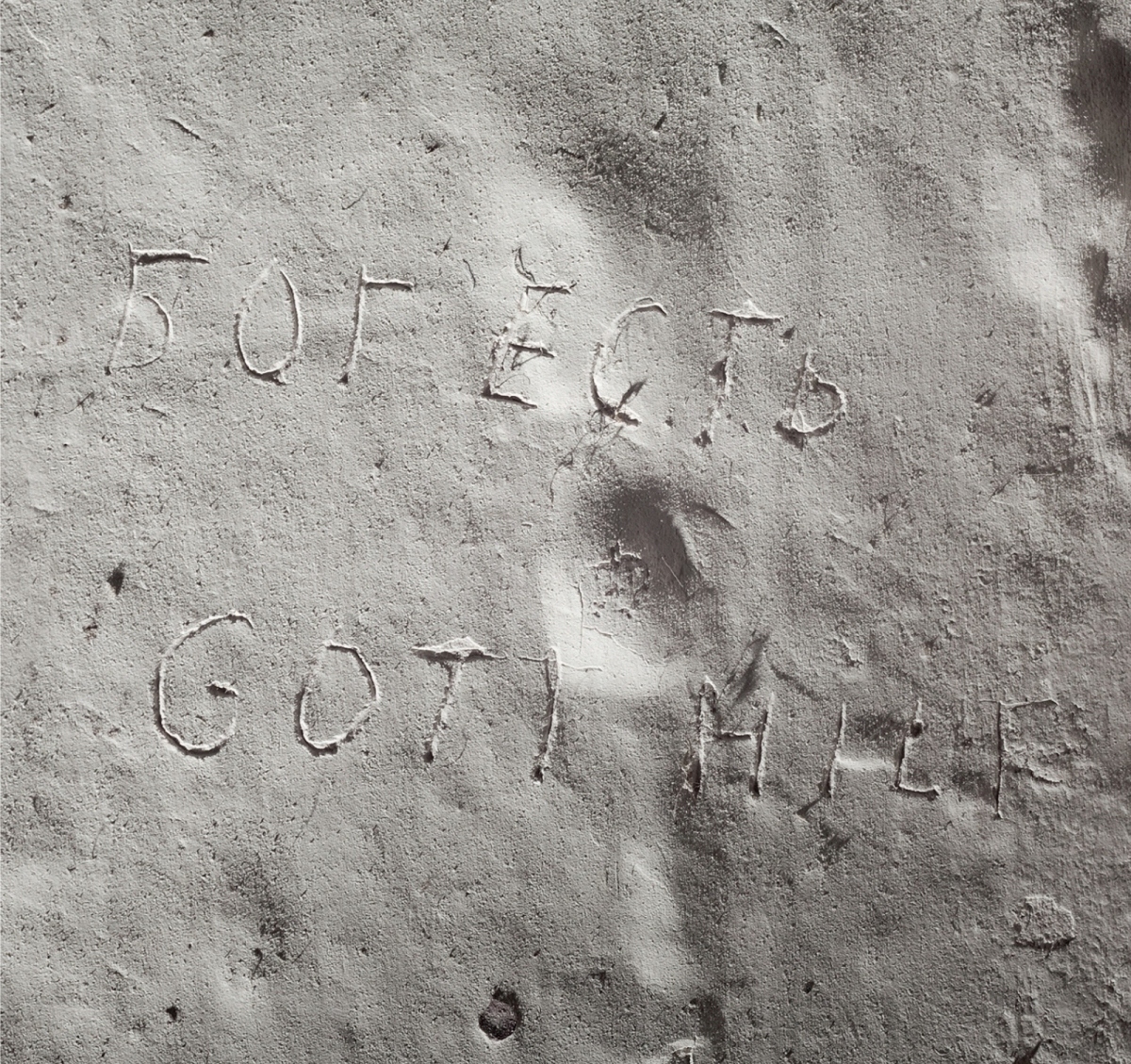

“God exists” and “God helps”

“Horst Riewoldt, Rathenow, 16.9.31, DEATH SENTENCE, 24.3.53.” On March 24, 1953 a Soviet Tribunal sentenced baker Horst Riewoldt to death by firing squad on charges of espionage and organizing an underground group, but the following month the Supreme Court of the USSR replaced the death sentence with 15 years in labor camps. Riewoldt was released after 2.5 years. In February 1956, he got married, and on his wedding day he and his wife escaped to West Berlin. Rehabilitated in 2002 with the ruling of the Chief Military Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation.

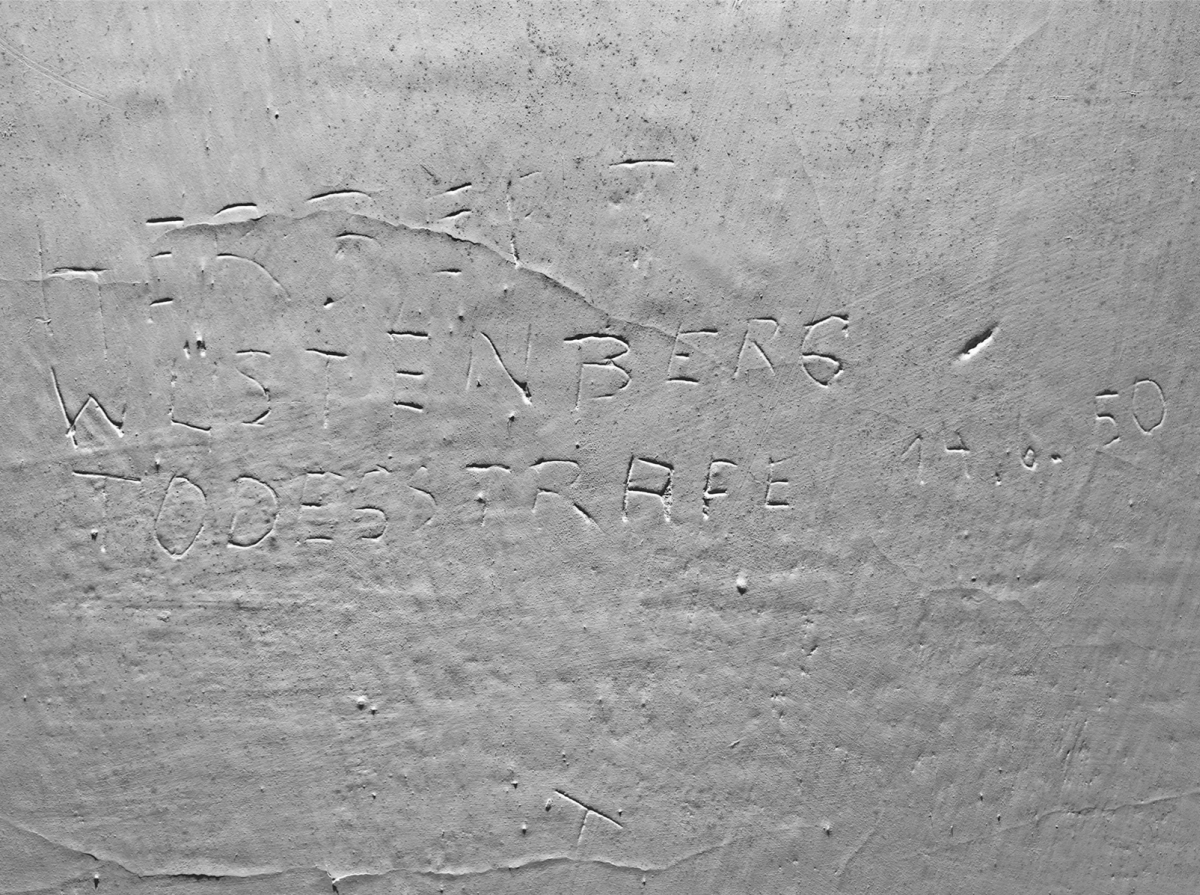

“HERBERT WÜSTENBERG, DEATH SENTENCE, 14.6.50.” Herbert Wuestenberg was sentenced to death for espionage. The Supreme Court of the USSR declined his clemency appeal. The sentence was carried out in Moscow on October 13, 1950. Herbert’s family received information about their missing relative only after 50 years.

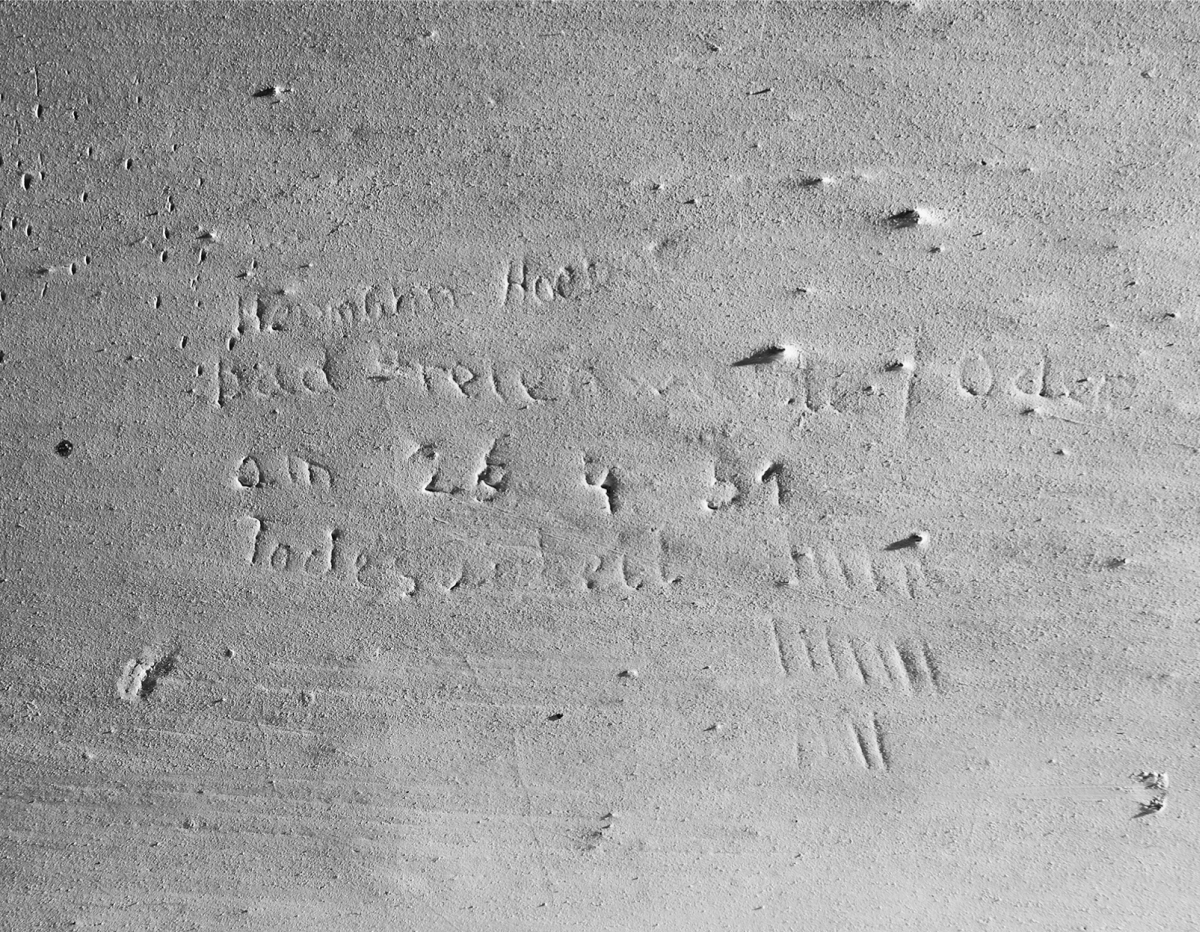

“Hermann Hoeber, Bad Freienwalde/Oder, on 26.4.51, death sentence.” Hermann Hoeber was sentenced to death for espionage. The sentence was carried out in Moscow, on July 1, 1951. Rehabilitated posthumously in 1999.

“No freedom for 10 years.”

The prison building was surrendered to the municipality of Potsdam after the final withdrawal of Soviet troops from Germany in 1994. It currently houses a memorial complex dedicated to the history of the prison, fates of the prisoners, and the conditions that they were kept in.

Photographs of graffiti from Ines Reich, Maria Schulz (Hrsg.), Sprechende Wände, Potsdam: Metropol Verlag, 2015