Saints: Panos Kefalos Explores Inner Demons by Capturing Refugee Children

Photographer, videographer. Lives in Athens. Published his works in LensCulture, Fotografia Magazine, Vice. Exhibited his works during group and solo exhibitions in Greece and Portugal. In 2016, his project Saints became one of the winners of LensCulture Street Photography Awards.

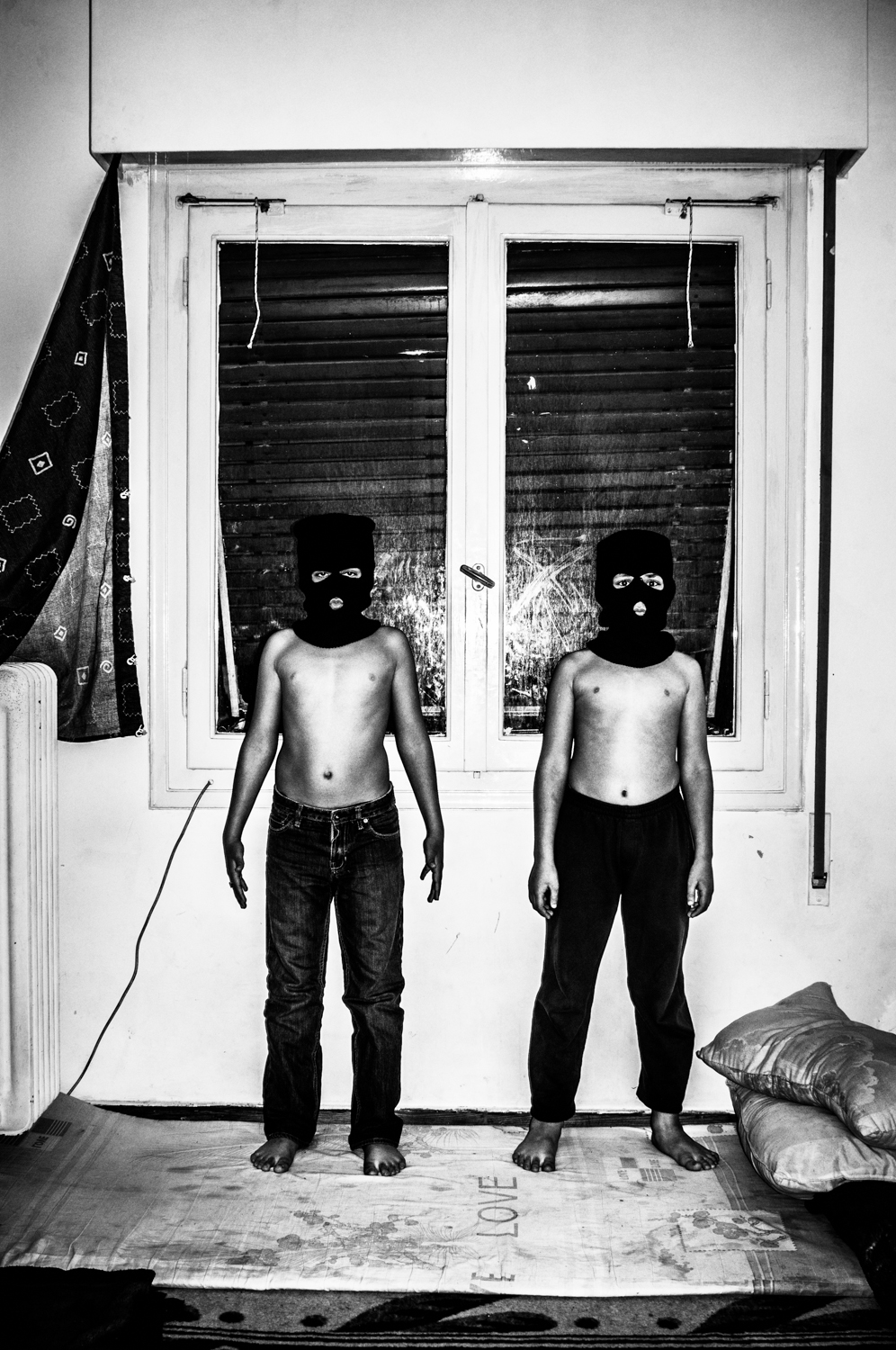

— Saints started in November 2012 and lasted 3.5 years. Back then I was taking pictures of Victoria Square, in downtown Athens. While working there I met with Afghan refugees, part of the community that lived in that neighborhood. What first caught my attention was the children’s games, where cruelty and tenderness blended.

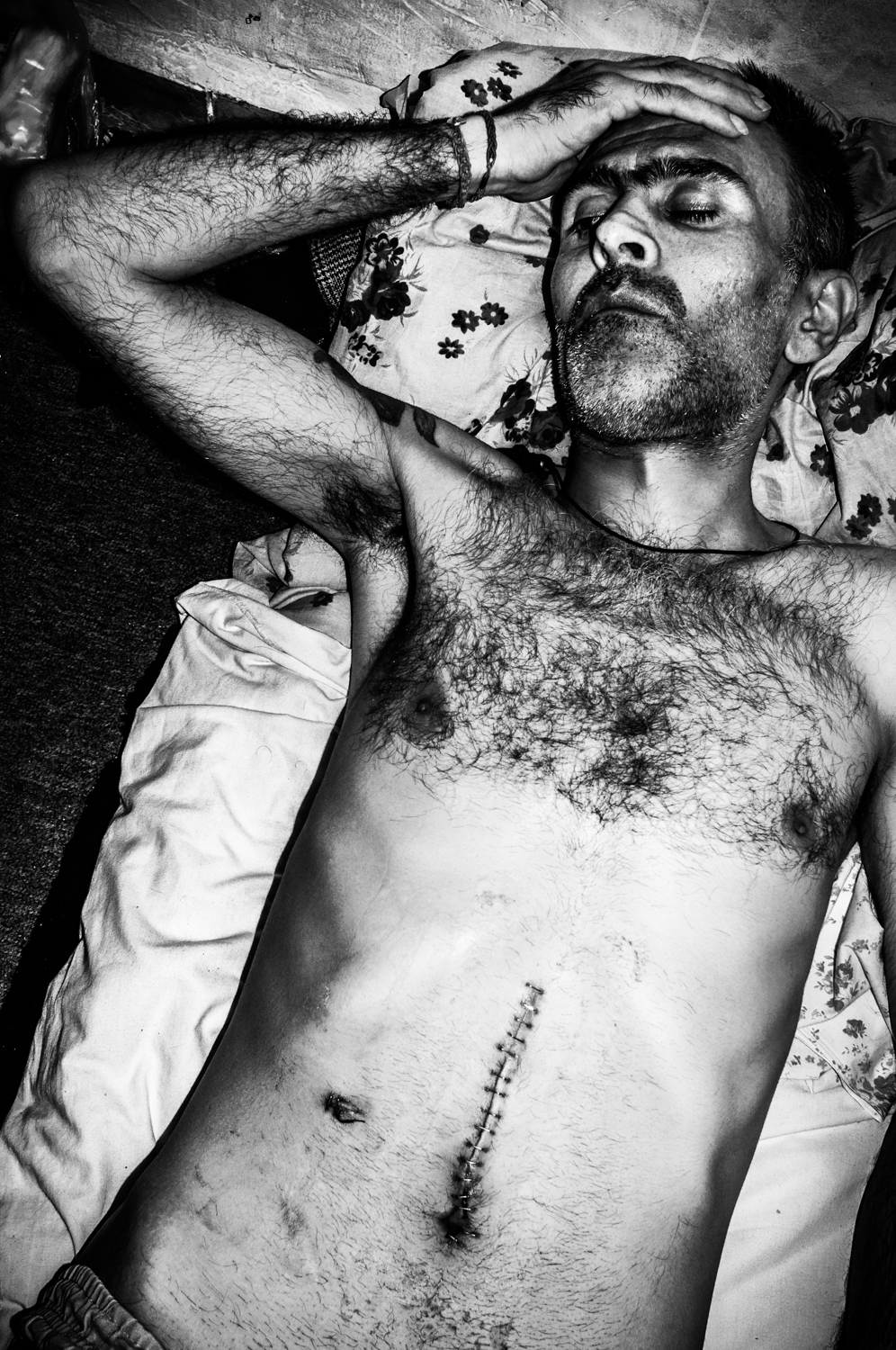

Getting to know them was the spark that caused old memories, images, and fears to come back to life. This whole project is also a personal journey. I knew that I wasn’t just taking pictures of their daily lives here in Athens. I was trying rather to capture my own life through theirs, through people I didn’t know. These photos don’t tell any stories. They are a free association of images, reflections of the way I felt about our encounter.

The kids themselves showed me the places where they played, worked, practiced their religion. That is how I eventually visited a mosque during the Muharram festival – invited by a family of friends – and I developed a closer bond with the community.

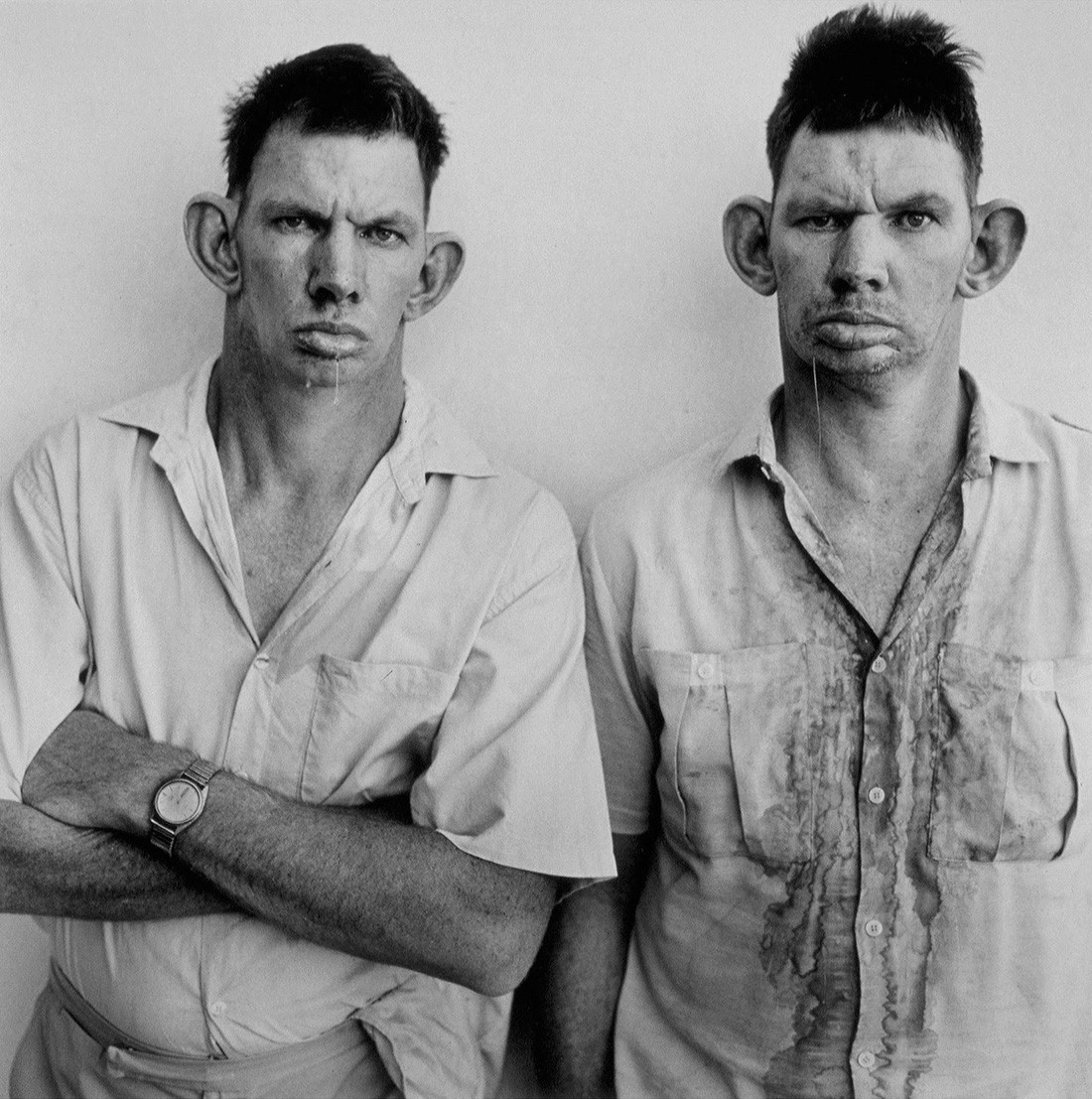

The lives of refugees is really harsh, they face a dangerous and taxing journey before reaching Greece, a journey during which they’ve usually lost all their possessions. Some of the kids had to work, selling sunflower seeds and bread in the streets: despite all that, many tried to find time to attend school. Most people had to go to the soup kitchen for food. They lived in old buildings downtown, buildings they rented in groups of many families. More rarely, some NGO was able to provide housing for them. Other families had to live on the street for a long time, or if they were luckier they’d become squatters or find a spot in a refugee camp.

The heroes of this project are the kids. I really bonded with three of them (and with their families as well), each at a different stage of my work: Sayid, Sohrab and Elias. They often acted as my assistants, they welcomed me into their homes and introduced me to their families and friends. Sometimes it wasn’t hard gaining their trust, in other cases it took some time. In all these years I wandered through the streets of Athens, following people I didn’t know, working only at night: I rarely saw the light of day while working on the project. I got into all kinds of homes, even some where one could feel threatened: but I was never anything less than myself. I lived by their side for three and a half years. We really got to know each other. I experienced new and powerful things, enjoying the truth that they taught me.

Saints made me relive moments from my own past. The hard part was finding a connection between my own experiences and the children’s, to establish a world we could both inhabit, to find some common ground. Only by taking some chances could I find my way out of this labyrinth: it took me some time and it was a constant struggle. I tried to let my instincts do my work for me, hoping to uncover something ancient and buried deep in my memory and subconscious – wishing to come across a past event that I needed to recollect, or that I need to experience again in the future. I wanted life to come pouring forth from these hidden and frightening landscape. This black and white visual style is just a means to an end, a way get me closer to my own world. I really love photographers whose life and work you can’t actually tell apart, like Anders Petersen, Daido Moriyama, Diane Arbus, Michael Ackerman, Antoine D’Agata, etc.

Saints is how I think of these children. The title refers to their martyrdom, to all that they’ve been through, to the pain they had to endure because of the war and to the terrible things they had to see. In my language, the word ‘martyr’ – which is a Greek word – can also mean witness.

The project ended in July 2016, when the book got published by Italian publisher Fabrica. I keep in touch with many of the children: we look each other up on Skype or Facebook whenever we can. Sometimes it can be difficult, because as time goes by their memory of the Greek language starts fading, as they’ve all left for other European countries where they can now live with their families. None of the children, not even one, lives here in Greece anymore.