Phantom Syndrome: Ethnic Koreans in Ukraine

Korean photographer. Studied photography and film in Kyungil University (South Korea). Held solo exhibitions in Kyiv (Shcherbenko Art Centre) and Seoul.

— I thought that after the deportation of 1937 (when ethnic Koreans were resettled from the far eastern region of the USSR to Central Asian republics) Koreans live only in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and maybe on Sakhalin. However, when I was taking photographs for my project about Chornobyl in Ukraine in 2015, I found out that there are also many ethnic Koreans living in Ukraine — according to the statistics, about 30,000. With the help of the embassy of the Republic of Korea in Ukraine and the Association of Ethnic Koreans I received information about some of them. I managed to take portraits of 20 families in Kyiv, Dnipro, Kryvyi Rih, Kremenchuk, and smaller towns of Ukraine.

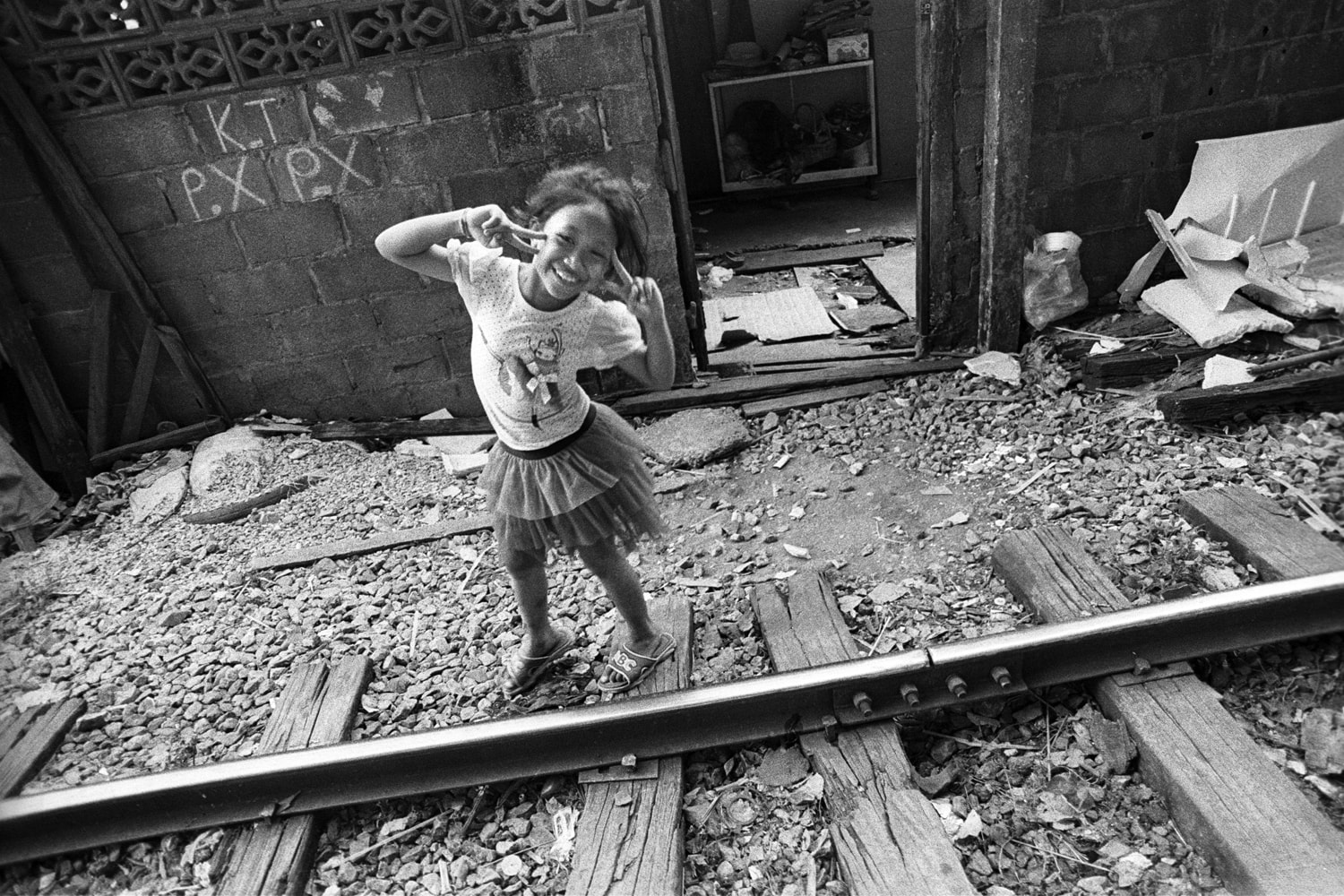

I see phantom syndrome in how ethnic Koreans identify themselves — it’s like pain in an amputated limb. This pain is mutual: there are almost no ethnic Koreans in Korea now, and ethnic Koreans are not part of the Korean nation anymore.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the meaning of a ‘united nation’. I have a hope that if Koreans try thinking about their identity more often, North and South Korea will reunite one day.

I usually talk to the subject for about two hours, and then spend another half an hour taking a portrait. I think that a good photograph is the one that lets me discover something new. This happens only when you get used to the environment and lose the tourist outlook on things.

I started my project with questionnaires, where I asked people to answer the questions: “Where were you born?”, “Where did your parents use to live?”, “How did you end up in Ukraine?” and so on. Some of them asked me where I was from, and were worried whether I am ever going to show these pictures in North Korea.

It has been 80 years after the deportation, and almost nobody from the first generation deportees is alive — I met only two people. My pictures mostly feature Koreans from the second, third, and fourth generations. None of them is thinking about going back to Korea; and almost none of them speaks Korean. They have retained few things from their culture, probably only in interior — small tables or cutout calendars on the wall. Their faces are almost the only thing that speaks to their roots.

New and best