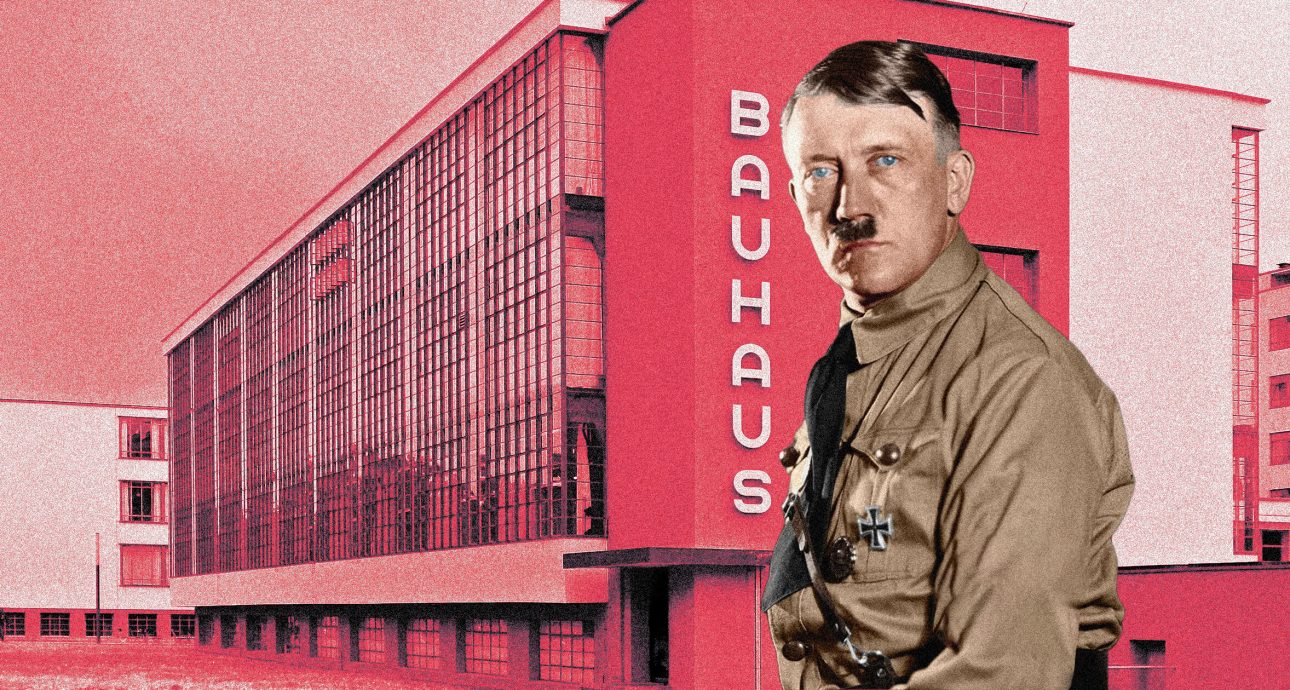

Flat Roof — From the Evil: How Hitler Destroyed Modernism

On April 11, 1933, based on a report from the prosecutor in Dessau, the Nazi police and officers of the Storm Detachment of the Third Reich raided and closed down the Berlin premises of the Bauhaus. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was heading the school, contacted Alfred Rosenberg, the Fuhrer’s authorized representative for general spiritual and ideological education, in order to save the institution. He was given a condition: to remove “the communist Kandinsky” and “the Jew Hilberseimer” from the teaching staff, as well as to approve the curriculum in the new Ministry of Education. Mies van der Rohe refused, and the school was permanently closed. This is what preceded it.

The New Architecture

The rapid development of industry planted among architects of the late 19th century the idea that now every person, regardless of their wealth or origins, would have access to housing – it became cheaper and faster to build. This gave rise to a new aesthetic, as mass production inevitably leads to standardization and simplification of forms. Modernism emerged with its directions: functionalism, rationalism, constructivism. Function and utility took precedence, and the elements that distinguished the architecture of the rich from the architecture of the poor were no longer necessary.

The new aesthetic emerged simultaneously in different parts of Europe. Its rapid spread and uniformity were rooted, not least, in the similarity of the political preferences of its creators: practically all supporters of the rationalization of art adhered to left-wing views and supported revolutionary changes. This popularized the slogan “Art should not be a great pleasure, but happiness and life for the masses.”

Bauhaus Building in Dessau. Architect: Walter Gropius. Opened in 1925. Photo: SVdesign / Flickr.

In Germany, this movement was represented by the production union “Werkbund,” which included architects, artists, and entrepreneurs. Its most famous members were artists El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko, and architects Walter Gropius, Bruno Taut, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. They sought to create a new industrial art and a new architecture. In 1919, another school emerged called the Bauhaus. Gropius established it by combining the Higher School of Visual Arts with the State Construction School. The architects of these institutions leaned towards functionalism, one of the directions of modernism.

At the Bauhaus, students extensively studied the composition of buildings, proportions, rhythm, and color theory. They independently worked with metals, fired ceramics, and wove textiles. The school aimed to foster a “new guild of artisans without class distinctions” who, through their creativity, would shape a new way of life for people.

The social-democratic government at the time aimed to address the housing problem in Germany, coinciding with the ideas developed by the modernists in mass housing construction.

Haus am Horn in Weimar. One of the first projects of the Bauhaus school, realized in 1923. Architects: Walter Gropius, Georg Muche, and Adolf Meyer. Photo: Doctor Casino / Flickr.

Gropius Houses in the Törten Settlement. Constructed between 1926 and 1928. Photo: riesebusch / Flickr

The new approach to designing rational-type structures was called Neues Bauen, meaning “new building” in German. In these new buildings, a flat roof became predominant, which was previously used in Germany primarily for industrial facilities. After all, the simpler the forms, the easier the construction process. The walls were left untreated on the exterior and were simply whitewashed or painted concrete. Door and window openings were simple, devoid of ornamentation, but large enough to allow ample sunlight into the interior spaces.

Flat roofs, which were previously used in Germany mainly for industrial structures, emerged in the new buildings.

The architects needed to provide housing for as many people as possible, quickly and at a minimum cost. Therefore, they created small residential structures with built-in furniture and appliances, where everything had a specific function. These dwellings seemed to dictate a certain way of life. Examples of such were the houses by Gropius in the Törten settlement and Ernst May in the new districts of Frankfurt.

The architects of the “new building” movement sought to shape people’s everyday lives, enabling them to escape from a “burdensome past and move quickly towards a bright future.” Bruno Taut, the chief architect of the Berlin state housing cooperative GEHAG, even stated that “artists must compel people to be happy.” By the way, his modernist housing complexes in Berlin are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

The Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart became the epitome of the “new building” movement, constructed in just 21 weeks in 1927. It was designed by architects of diverse origins, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Hans Scharoun, and others. It is believed that this project gave rise to the term “International Style.”

Hans Scharoun's House in the Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart. Photo: Lichtblicke / Flickr

‘Right-wing’ architecture

People were not prepared for such drastic changes in lifestyle and aesthetics. The wave of revolutionary enthusiasm subsided, and they longed for something visually more familiar, despite the evident advantages of the new method of building construction. Similar processes took place in the United States and the USSR, where there was a temporary shift from functionalism or constructivism to neoclassicism.

The ideas of “new building” were popular among the intelligentsia of large cities and industrial centers, but not among peasants and the petite bourgeoisie. They adhered to traditional values, and conservative right-wing figures held authority among them. Hitler specifically targeted this demographic when he came to power.

Saarbrücken State Theater. Constructed in 1936. Architects: Paul Baumgarten and Gotthelf Bem. Photo: Dguendel / Wikimedia Commons

In 1925, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg became the President of Germany, publicly refuting Germany’s guilt for starting the war as stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles and calling on Germans to consolidate around the national idea. That same year, Hitler’s book “Mein Kampf” was published, and Germany was leaning towards the “right”.

Almost all functionalist architects sympathized with left-wing ideas, some joined parties, and it was natural for conservatives to see them as enemies of the traditional order. The newspapers they owned referred to the Weissenhof estate in Stuttgart as an “Arab village in a German city” or the “new suburb of Jerusalem,” and the architects themselves were accused of trying to “proletarianize” the German people through their architecture.

It reached absurdity: architect Hermann Muthesius wrote that the “new form leads to an unimaginable excess of lighting standards in residential spaces due to ribbon windows that encircle the buildings.”

The house of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in the Weissenhof district, Stuttgart. Photo: GhostOfDorian / Flickr

Later, as the leader of the Nazi Party, Hitler instructed Alfred Rosenberg to create an organization for the dissemination of Nazi ideas among art practitioners. Thus, in February 1929, the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (Fighting League for German Culture) was established. Its aim was to “clarify to the people the connection between questions of race, art, science, and traditional values.”

The main targets of the organization’s attacks were artists, sculptors, and architects who were deemed to have “betrayed the national idea and contributed to the degeneration of the nation.” One of the members of the Kampfbund, architect and art theorist Paul Schultze-Naumburg, was the most active “exposer” of the modernists. He seriously compared flat roofs with pitched roofs in his book “Flat or Pitched Roof,” and in his book “Art and Race,” he emphasized that the characteristics of any artistic work were determined by the racial identity of its creator. Le Corbusier he called a “secessionist” and a “cultural Bolshevik,” while his colleagues were referred to as “rootless cosmopolitans.”

The political views of the architects worsened the situation. In 1928, Hans Mayer, a Swiss architect openly supportive of communist ideas, replaced Gropius as the director of the Bauhaus. He proclaimed the motto “People’s needs instead of luxury needs,” and due to his political views, he was dismissed by the mayor of Dessau in 1930. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, an apolitical figure, took Mayer’s place.

Nazi architecture

At the end of the 1920s, parallel to the rest of the world, Germany began a transition to neoclassicism. This was facilitated by political transformations in the country. Neoclassical architecture was designed using the same functional methods, but with facades adorned with elements reminiscent of classical or Renaissance architecture, such as columns, cornices, and portal frames. The Third Reich considered itself the successor to the Second Reich, the imperial Kaiser-era Germany that existed from 1871 to 1918. Through neoclassicism, they artistically emphasized the ideological continuity of the empires, which is a characteristic feature of German neoclassicism.

Neoclassicism artistically emphasized the ideological continuity of German empires.

Nazi Germany’s architecture also embraced classical and medieval historicism, as Hitler considered classical architecture to be the epitome of beauty and functionality, symbolizing the greatness of ancient empires that he aspired to surpass.

With the dissemination of Nazi ideology in Germany, the “National Homeland Style” gained popularity, drawing inspiration from rural artisanal traditions. It incorporated elements such as

Traditional wooden construction with an exposed exterior framework, characteristic of rural architecture in Northern Europe.

Camps where the dissemination of ideas and the education of youth took place, an example being the Hitlerjugend camps.

Dormitory in Hermeskaila. Constructed in 1936 in the "Homeland Protection Style." Photo: P170 / Wikimedia Commons.

Repressions.

In 1932, repressions against Bauhaus as a stronghold of “cultural Bolshevism” began, and the municipal council of Dessau raised the question of demolishing the school building. Ultimately, the building was not destroyed, but Bauhaus was stripped of its status as a state educational institution. Mies van der Rohe was forced to exclude politically active students from the school and dismiss such teachers, and they left the country.

The attack on architects was accompanied by an escalation in the press. The central printed organ of the Nazi party, Völkischer Beobachter, wrote that among the prominent representatives of the “new building” there were hardly any Germans: “The Russian Kandinsky, the American of German descent Lionel Feininger, the Hungarian Moholy-Nagy, the Russian Jew and communist El Lissitzky, followed by Chavannes, Le Corbusier, Gour, the communists Perri and Rodchenko…”

And then: “They want to kill individuality in people; they want collective beings because the ultimate goal of these creators is Marxism, communism. Therefore, the schemes of the great cities by Hilberseimer or Le Corbusier are completely logically linked to the projected new Soviet architecture.”

Mies van der Rohe even relocated Bauhaus from Dessau to Berlin and registered the school as a private institution, hoping it would provide protection. However, three months later, on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor, and the fight against “cultural Bolshevism” became part of the state ideology. Hitler considered Constructivist architecture, abstract painting, and flat roofs as “Jewish inventions.” That same year, Bauhaus was closed, and the Deutscher Werkbund, which was the starting point of the “new building” movement, was dissolved in 1934.

Hitler regarded Constructivist architecture, abstract painting, and flat roofs as “Jewish inventions.”

Architects, many of whom had Jewish origins, began to emigrate, while those who remained were repressed. During a search at the Berlin Bauhaus, around 30 students were arrested.

Erich Mendelsohn, Adolf Rading, and Josef Frank emigrated to England, France, and Sweden, respectively, saving their lives. Walter Gropius went to the United Kingdom and later to the USA, where he became a professor of architecture at Harvard University. His buildings emerged in the United States, Europe, and even the Middle East.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also moved to the USA, where he headed the architecture department at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. It was there that he created his most famous buildings: the IBM Plaza, the Chicago Federal Center skyscraper, and the Seagram Building, which he designed with Philip Johnson. Mies van der Rohe returned to Berlin in 1965 at the age of eighty. A year before his death, he completed the modernist building of the New National Gallery.

The New National Gallery in Berlin. Constructed in 1968. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: A. Savin / Wikimedia Commons.

Bruno Taut was deprived of his professorial title and expelled from the Academy of Arts by the Nazis. He emigrated to Switzerland, and later architect Isaburo Ueno brought him to Japan. Architect Hans Poelzig was completely prohibited from working due to his leftist views.

Ludwig Hilberseimer, whom the Nazis demanded to be expelled from Bauhaus along with Wassily Kandinsky, emigrated to Chicago to work with Mies van der Rohe. There, he became the head of the Urban Planning Department at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture and the director of the Chicago Department of City Planning.

Hans Mayer, the director of Bauhaus who was dismissed due to his communist views, initially went to the Soviet Union, where he built socialist towns, and then moved to Mexico. Architect Hans Scharoun, known as the author of the Berlin Philharmonic, remained in Germany. During the war, he secretly depicted his architectural ideas in numerous watercolors, mentally preparing for the world that would come after the victory over the Nazis.

Berlin Philharmonic. Constructed between 1960 and 1963. Architect: Hans Scharoun. Photo: Alexander Rentsch / Flickr.

Le Corbusier was living in Paris at that time. During the occupation of France in 1940, the Nazis closed down his studio, and he and his wife moved to a farm away from the capital.

There were representatives of the Werkbund and Bauhaus who deviated from modernism and embraced Nazi ideals, such as Peter Behrens, one of the founders of the production collective. However, none of these architects became prominent, and some faced repression despite their compliance.

Hitler destroyed modernism in Germany, and for 12 years it was frozen in architecture, symbolizing totalitarianism and power. But after World War II, during the country’s reconstruction, modernism made a comeback.

Cover photo: Spyrosdrakopoulos / Wikimedia Commons

New and best