Ancestors Leave the Shadows: Why the Paradzhanov’s Film is This Year’s Most Crucial Cinema Premiere

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors has an enormous significance — both artistic and political. This film to the Ukrainian poetic cinema is what Citizen Kane is for Hollywood — a genre-defining picture that made an impact within and outside the circles of classic Ukrainian cinematographers: the Illienko family (Yurii Illienko rose to prominence as the cameraman on Parajanov’s film), Leonid Osyka, Borys Ivchenko, and others. The poetic spirit of Parajanov is felt in current Ukrainian releases, too. For one, Marysia Nikityuk’s When the Trees Fall is steeped in the atmosphere of an ethnographic fairytale. Oles Sanin’s famous Mamay was also created under Parajanov’s influence.

According to Parajanov’s contemporaries, his first short film — the lost Moldavian Tale — already had everything that made the author of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, The Color of Pomegranates, and Ashik Kerib famous: epic folklore, exotic ethnography, and visual poetry. Still, the director made stereotypically Soviet films in the vein of social realism for the following ten years.

His most successful early picture was The First Lad, a comedy about a soldier discharged from the army who builds a football stadium in his native village, which 19 million Soviet viewers watched. It is a masterfully crafted film — among its highlights are lengthy continuous takes of crowd scenes. However, everything drastically changed when Parajanov watched Ivan’s Childhood, written by Tarkovsky. Parajanov had musical and ballet education, so he started filling the frame with harmonious imagery and music, including the music of the spoken word and film editing. This aspect makes all his pictures about the past timeless and imparts universal cultural significance.

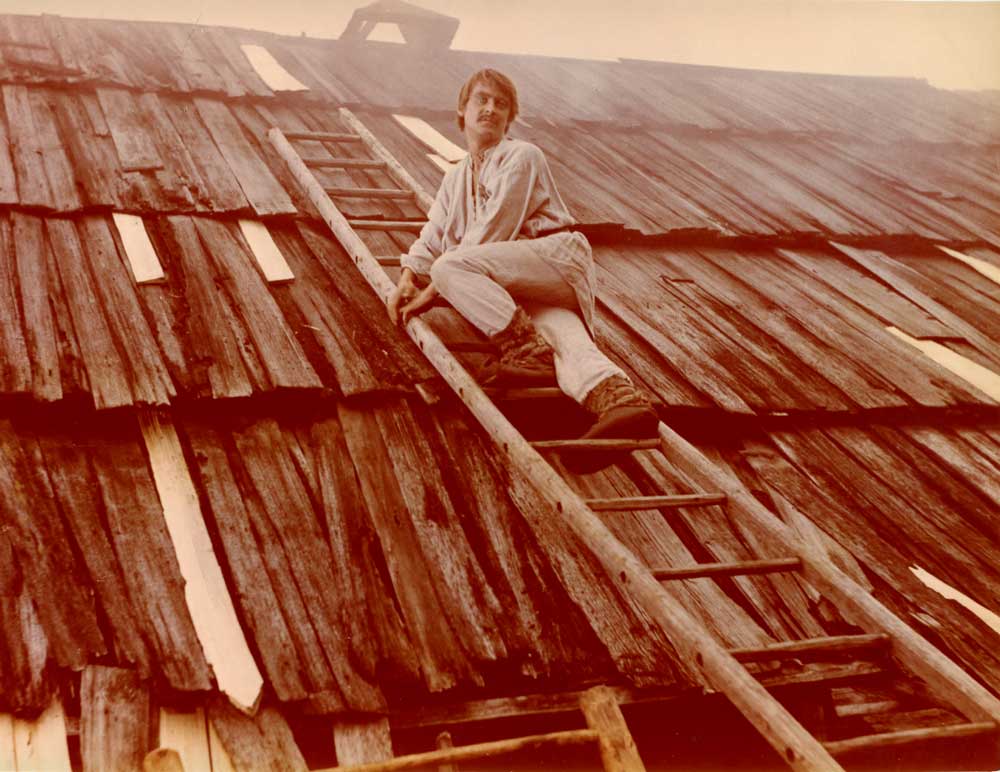

Ivan Mykolaychuk as Ivan Paliychuk. Photo: Dovzhenko Centre

One thing makes Parajanov directing Shadows of the Forgotten Ancestors all the more surprising. Although he was always bad at politics, he managed to smoothly pull off perhaps the only political move in his life, using the opportunity to work on an official film for Kotsubynskyi’s anniversary to make a statement of his own. He drew on the republic’s best talent to assemble a film crew. Also, he took the risk of casting then-beginner actor Ivan Mykolaychuk for the lead role. Finally, he went as far from the capital’s officials as possible to shoot the picture.

Parajanov smoothly pulled off perhaps the only political move in his life, using the opportunity to work on an official film to make a statement of his own.

The story of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is closely linked to Parajanov’s personal story and that of Ukrainian intelligentsia opposition in the 1960s and 1970s, which strikingly resonates with what we see today. The film became a symbol of the Ukrainian national resistance against the Soviet repressive machine.

The first political protest in Ukrainian SSR’s history took place at the Kyiv premiere of the film at the Ukraina cinema on the 4th of September 1965. Later, many legends have grown around the rally, like with everything connected to the Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. They say the rally was spontaneous — at least Parajanov knew nothing about it. Still, the director himself set the tone. Addressing people in the auditorium, he bitterly recounted how much blood and nerves it cost him to argue for his vision for the film with Soviet officials, who were notoriously intolerant of freethinking in the Ukrainian SSR, where the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was still remembered. Then poet and literature scholar Ivan Dzyuba took the stage and spoke about the Ukrainian intelligentsia arrests that took place the day before. Poet Vasyl Stus and journalist/activist Vyacheslav Chornovil rose from their seats after that and invited the viewers to support the protest. The rest is history — everybody involved went to prison, and Stus died behind bars.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is actually the first-ever essentially non-Soviet film about Ukraine. The story of Hutsul Romeo and Juliette steeped in the free spirit of the Carpathian Mountains (Parajanov said he could feel it because he was born in a mountain land) had no place for the ruling party and government.

In no small measure, the film’s longevity and impact are due to Parajanov finding his own mythology of the Ukrainian Carpathian Mountains rooted in the Hutsul traditions. That is to say that he not only showed Hutsul customs through authentic costumes, furniture, and nature — he built his own ethnographic rituals on the foundation of Hutsul folklore, as in the famous scene of Ivan and Palahna’s wedding, in which they wore horse collars.

The story of Hutsul Romeo and Juliette steeped in the free spirit of the Carpathian Mountains had no place for the ruling party and government.

The director showed the Carpathian Mountains and forests as a land of fantasy, in which people have a special relationship with nature and one another. Life, death, love, and even daily life were sacraments there. In the nature scenes — at the river and in the forest — the camera keeps moving, unstoppable like an elemental spirit living among people. The poetry of Parajanov’s visual imagery paradoxically combines with the almost documentary filming style. This is why this picture keeps us amazed to this day.

Ivan Mykolaychuk as Ivan Paliychuk. Photo: Dovzhenko Centre

The film became not only another peak of the Ukrainian national spirit’s elevation but also a convenient pretext for party officials and the KGB to crack down on the freethinking in the republic. Through the years, the viewers had a hard time believing that Soviet artists had to sacrifice their careers, well-being, and even their own lives to create — like Mykola Trehub, who broke under pressure and took his life.

The film became not only another peak of the Ukrainian national spirit’s elevation but also a convenient pretext for party officials and the KGB to crack down on the freethinking in the republic.

This is why the re-release of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is especially important now, at the height of the war with Russia, which is trying to “reassemble” its USSR-like abomination. When you watch it, remember that artists, poets, and cinematographers are protecting their independence from the KGB/FSB repressive machine at the frontline with arms in hand. The only difference is that now we will win for sure.

Photos: Dovzhenko Film Studios / Archives du 7eme Art / Photo12 via AFP

New and best