Children Against Sinners: The Marginal Creativity of Henry Darger

Henry Darger was born in 1892 in Chicago. His mother died when he was four; his father barely went outside because of his own health problems. At four, Henry went shopping and did household chores by himself. The family barely made ends meet, so Darger’s younger sister was sent to an orphanage — according to the artist’s memories, he saw her only in childhood.

At school, Darger painted rather well and took an interest in the American Civil War. Despite his academic success, his teachers didn’t like him — he often corrected their mistakes. His classmates had a problem with his ‘provocative’ behavior — as Darger later recalled, during classes and breaks he made ‘strange sounds’ with his nose and mouth.

Because of Darger’s behavior, the school doctor diagnosed him as mentally disabled and sent him to a special home for children that was located in another state. According to Jim Elledge, the artist’s biographer, the staff at the home would frequently beat children. According to another researcher, John MacGregor, at about the same time the home was in the middle of a scandal: the doctor there supposedly used the bodies of children who had recently died to teach anatomy to students. The memories of living in the home would later be featured in the artist’s book.

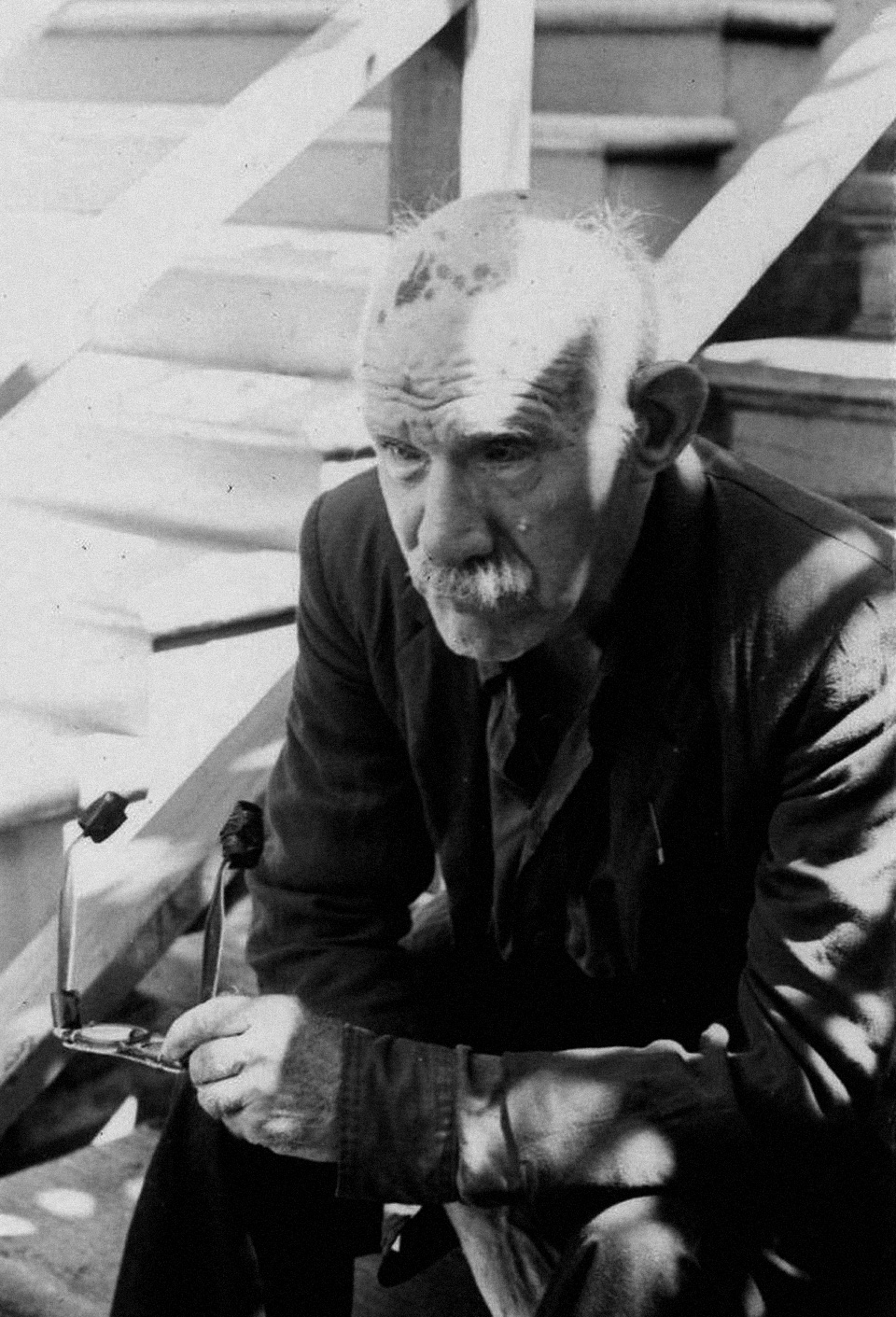

Henry Darger. The photograph was taken in 1971, two years before the artist’s death. Photo: Wikipedia

In 1900, Darger’s gravely ill father was placed into a Catholic mission, where he soon died. Henry found out about it from a letter. Grieving, he became aloof and didn’t talk to anyone for several weeks.

Darger tried to run away from the children’s home. One time, he was caught by shepherds at a farm where students worked during the summer holidays — he was then tied to a horse and made to run after it for several kilometers as a punishment. The second time, he jumped onto a freight train, but got afraid of the thunderstorm, and surrendered himself to the police at the nearest station.

Finally, at 16, Darger, together with two other children, succeeded in running away from the farm, and after several days ended up in Chicago. For some time he worked some odd jobs, until he got employed at the Catholic hospital as a nurse’s aide — he would go on to work there for 50 years.

Girls and Guns

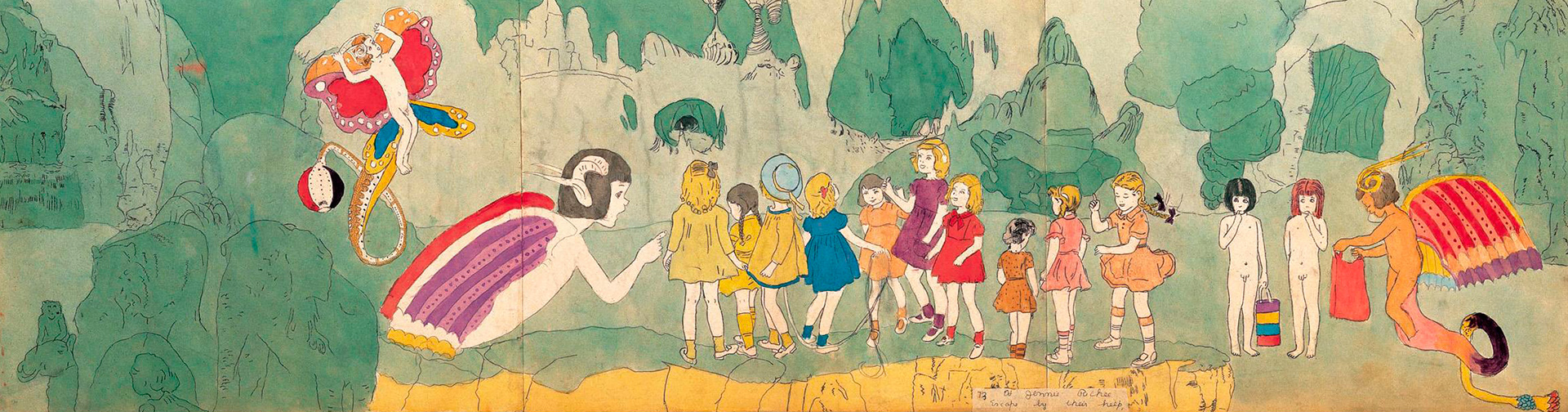

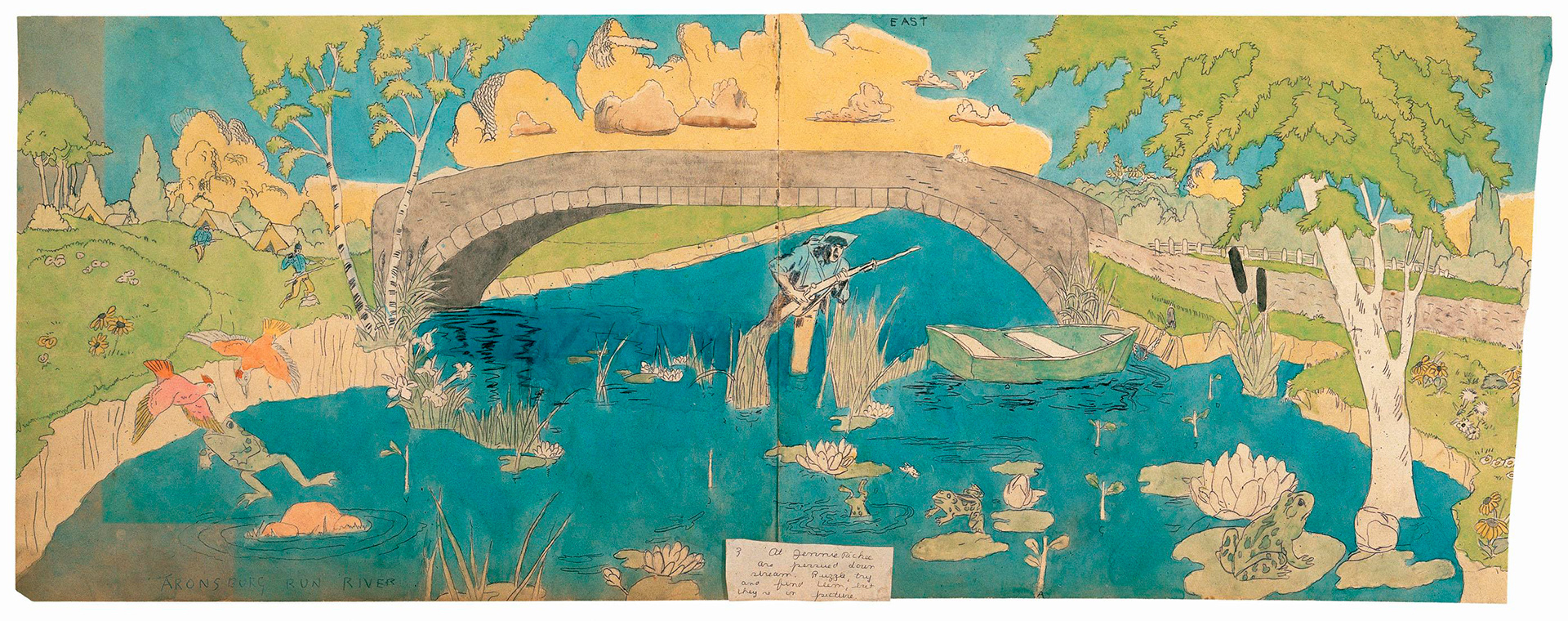

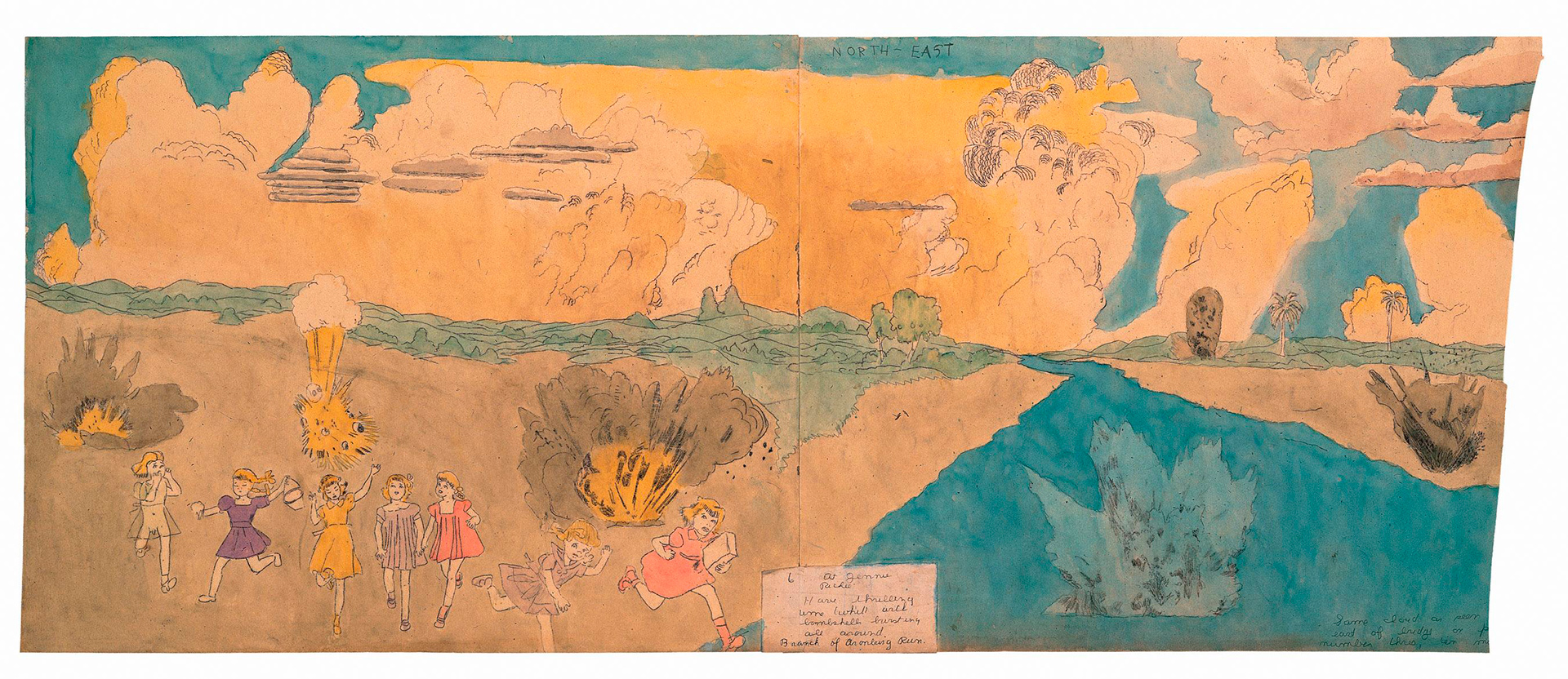

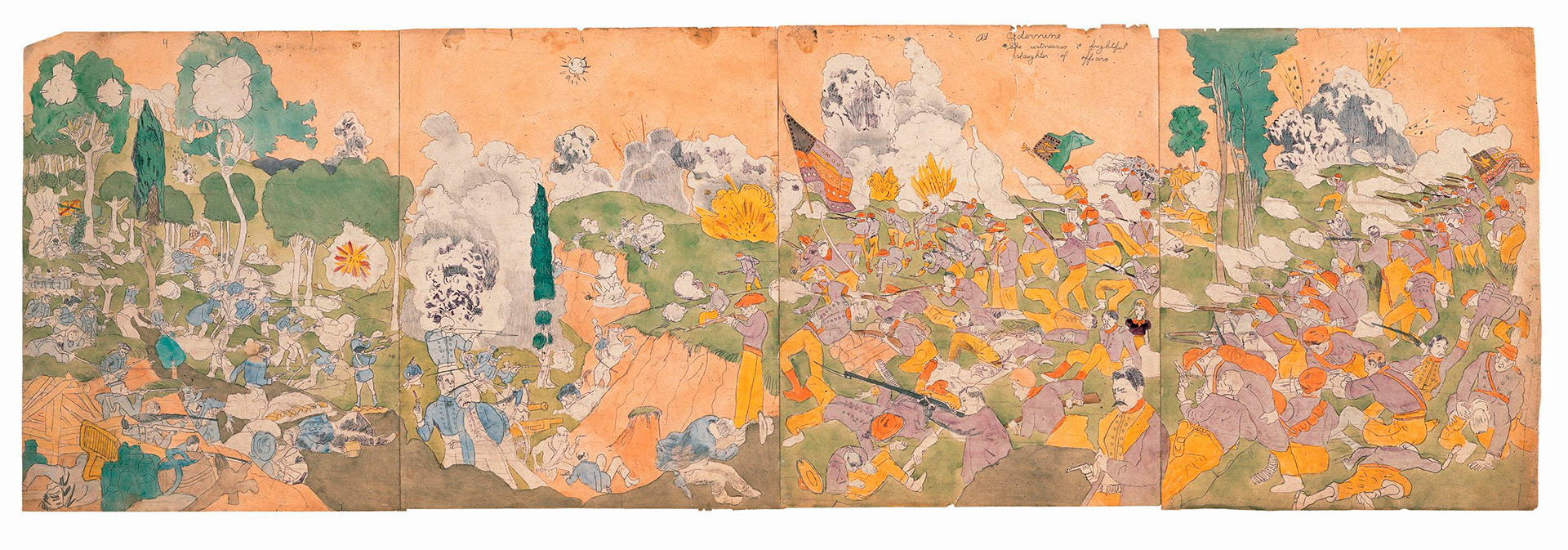

Soon after he started working in his new place, Darger also started writing a novel titled The Story of the Vivian Girls in what is known as The Realms of the Unreal. The action unfolds on an imaginary planet (according to Darger, a satellite of the Earth), in the country of Glandelinia where children rebel against the fallen Catholics who enslaved them. The uprising is headed by seven girls — Violet, Joice, Jennie, Catherine, Hettie, Daisy, and Evangeline, helped by a dragon. The four-year war ended with the children victorious, but at the cost of a high mortality rate.

The artist based his characters on real life, and sometimes were directly borrowed from The Wizard of Oz or Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Darger pays special attention to the war scenes: he even creates the marches that the sides play when they go out to the battlefield. In a special notebook, the author counts the fallen heroes and military equipment used during the battles.

In a special notebook, the author counts the fallen heroes and military equipment used during the battles.

Darger never learned to draw, so he was looking for his own techniques to create an image. At first, he ‘created’ collage: cut out silhouettes of people from newspapers, magazines and children’s coloring books, glued pictures on paper, and covered the result with paint. When Darger discovered that cutting out and looking for fitting sources took a lot of time, he changed the process and started making stencils.

He created a total of about 300 illustrations for the Vivian Girls. He painted some of the pictures on both sides on three-meter canvases.

Image: Anonymous gift in recognition of Sam Farber © Kiyoko Lerner / James Prinz

Image: James Prinz

Image: Museum purchase © Kiyoko Lerner / Gavin Ashworth

Image: Museum purchase © Kiyoko Lerner / James Prinz

You Won’t Like It

Darger’s creative work is characterized by his ability to combine naive sentimentality and excessive cruelty. In her book The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone, Olivia Laing draws attention to the fact that Darger’s characters always have a martyr-like, compassionate, or indifferent gaze. The combination of horror on the faces of the tortured girls and indifference in the eyes of their torturers leaves a heavy impression on the viewers.

The combination of horror on the faces of the tortured girls and indifference in the eyes of their torturers leaves a heavy impression on the viewers.

The artist’s ‘martyr’ works are so expressive that in 2000 his work was exhibited together with Goya’s engravings from the military series at the P.S.1 contemporary art center in Queens at the Disasters of War exhibition.

Because of such interest to the theme of violence and a reclusive lifestyle, some critics speak about a possible mental disorder of the artist. Psychologist John MacGregor considered Darger a serial killer who restrained his urges, getting the energy for his creative work from them. Later, however, MacGregor softened his diagnosis, and said that the artist had Asperger’s syndrome — people with this disorder experience trouble communicating and are interested with a limited number of topics.

Not everybody agrees with this approach: for instance, Michael Moon thinks that there is no excessive aggression in Darger’s work. In his opinion, the artist borrowed the scenes with excessive anatomical details from Scripture. Moon thinks that aggression in Darger’s work does not indicate mental issues, but a firm grasp on Christian literature that he consciously used when criticizing Catholicism.

Trash and Decay

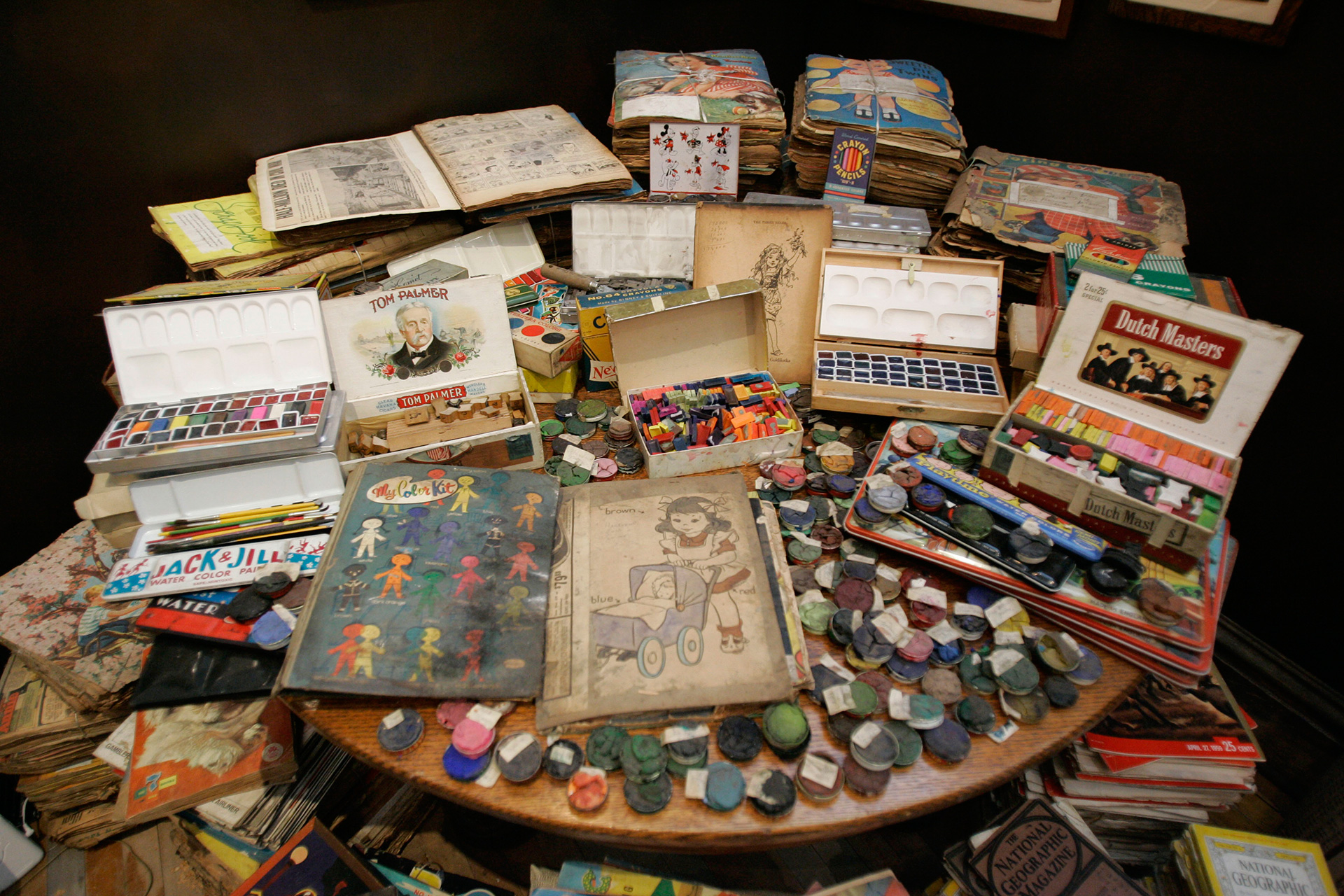

According to the neighbors, in the last years of his life Darger turned into a strange man who talked to himself or to people that he thought were in the room. He took trash from the street home: old newspapers, boxes, twine that he would spend hours unbundling in his apartment. He left the hospital and lived on welfare; he spent most of the money on enlarging the negatives that he would paste into his pictures.

Darger took trash from the street home: old newspapers, boxes, twine that he would spend hours unbundling in his apartment.

Sometimes Darger asked his neighbors to buy him soap or shaving foam for Christmas. Except for these infrequent requests, the artist barely talked to anybody. His state deteriorated, the entries in his diary became shorter. In 1972, the neighbors placed him in a care home at the St. Augustin’s Catholic mission. That was when the house owner, Chicago photographer Nathan Lerner, found his work. He decided to clean the apartment of its trash, and in addition to a hundred bottles of laxative, plastic figurines of Jesus and Mary, weird balls and a phonograph, Lerner found the pictures and the manuscript.

Image: Gift of Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner © Kiyoko Lerner / Gavin Ashworth

Photo: James Prinz / Kiyoko Lerner

He visited the artist several times and tried to talk about his work. Darger said that it was too late to do something about them and asked the house owner to destroy everything. Later, according to Lerner, the artist allowed him to keep the work. When Darger died after a year, Lerner took the pictures home, despite his wife being against it. And when the photographer died in the late 1990s, the rights for Darger’s legacy were inherited by his widow.

Today, Henry Darger is considered to be one of the most popular American outsider artists. His novel remains unpublished, but just the one work, At Jennie Richee, Escape During Approach of New Storm, was sold for $350,000 at Sotheby’s in early 2019.

Darger died in 1973, and was buried at the cemetery for the poor in Chicago. On his tombstone, his fans wrote that he was an artist and a protector of children.