Peter Dench: I Just Want to Be Entertained and I Want to Entertain

English photographer. Received World Press Photo award in 2003. TV presenter for Channel 4 News. Worked for GQ, Tatler, Marie Claire, The Sunday Times Magazine, Telegraph Magazine.

“I wouldn’t have [photography] any other way, it’s generally optimistic.”

In Russia, there’s a proverb «if you laugh a lot, then you’ll be crying a lot». Do you agree with that?

I’ve not heard the proverb, but yes.

Do you cry a lot?

Not personally, I rarely cry, but for me I think humor is an important tool in photography. What I’m trying to do with a successful book, or exhibition, or a magazine spread for me is that I could make people laugh, make people think and then make them cry, take them on a journey of emotions. If you have a photo essay that’s all about victims of an earthquake, you see devastating pictures, you kind of understand what’s going to come next, you go — oh, this is one of those stories. So, what I’m trying to do is to disarm people with pictures, so they don’t know whether to laugh or whether to cry. I think if you show someone three-four funny pictures, they think — oh, this is a funny story, and then you put in a photo of an alcohol-related car crash, and that picture suddenly drops them into another mood, so I agree with the proverb. But personally I don’t cry at all, ever.

You’re an optimistic person, right?

Well, in photography, the high is a high, the low is a low, and there is rarely any middle ground, and I wouldn’t have it any other way, it’s generally optimistic.

I was at the screening yesterday, and there was a lot of pain, a lot of illness, a lot of apocalypse around us, and I was like sitting there and thinking that I would rather see the picture of drunken Englishmen instead of what I see. I cannot deal with it, I cry a lot, how do you deal with it, with all these things that happen in the world?

Good question! The photographers I admire the most are the ones that do what I don’t, so I’m thinking of Marcus Bleasdale, who works in the Congo a lot, Tom Stoddart. Those photographers choose to cover serious things. I don’t think my work is any less valid than photographer’s who choose to tackle more of those subjects, I still think what I photograph is serious. You can’t be a photojournalist and just take funny pictures. You have to have something to say. I don’t suffer, because I understand, I think, and I know people who are trying to do something about it, so I think if I wasn’t proactive and trying to be a photographer and document what I think matters, then I’d suffer more.

But can you describe yourself as a photojournalist?

Absolutely, yes.

There are a lot of stereotypes about every nation: that Russians get drunk a lot, you English also, yeah? What is it like to be an Englishman?

I’m not ashamed to be English, but I’m not necessarily proud to be English either, it’s first world problems. So, what it is like to be an Englishman — you know, cliches exist, because they are true, some of them, and there are others that need to be challenged. But it’s complex, as it would be for any other nation. Alcohol is embedded in our society: pub culture, advertising, and that’s going to be difficult to change. But personally as an Englishman, I enjoy it very much. I think we are quite proud, we are more tolerant than people give us credit for. I’ve photographed the English for twenty years, and I’ve only been punched in the face once. So I think fear is in the head of the photographer. And generally we Englishmen are quite considerate and helpful.

You came here with the book «Dench Does Dallas», tell me about it.

But the book went missing for a week, so we have already found them yesterday, they are in the bookstore. I worked on assignment as a photojournalist in around 16 different countries, but my first three books were about the English, or the British. I was kind of becoming known as the funny English guy, so I wanted to develop a body of work away from Great Britain, same colored flag, but bigger market, different continent. I wanted to add to the visual archive that already exists, and Dallas was the first part where I’m trying to create a body of work, a Dench eye on America. I knew I wanted to go to America, I wasn’t sure where. And Olympus was sponsoring the trip, and they said where would I like to go, so I just went through the alphabet, and in the 1970-s there was an adult movie called Debbie Does Dallas. So, I ran through the alphabet and I got to D, and I thought, Dench Does Dallas. So maybe there will be more, Dench Does Denver, Delaware, and then global — Djibouti, Dresden, Dubai. Some photojournalists say “you have to know what you want to say and then go and get pictures that tell the story”. I’m the opposite, I decide a place where I want to go and then just go and hope I can make a portray of a place. I just spent two weeks in Dallas, I got up at 7 in the morning, I went out with the camera, I walked for twenty kilometers. Sure, there’s always some downtime. For the Dallas book I had no brief, the only instructions I had were to do what you do, which is both frightening and very pleasant.

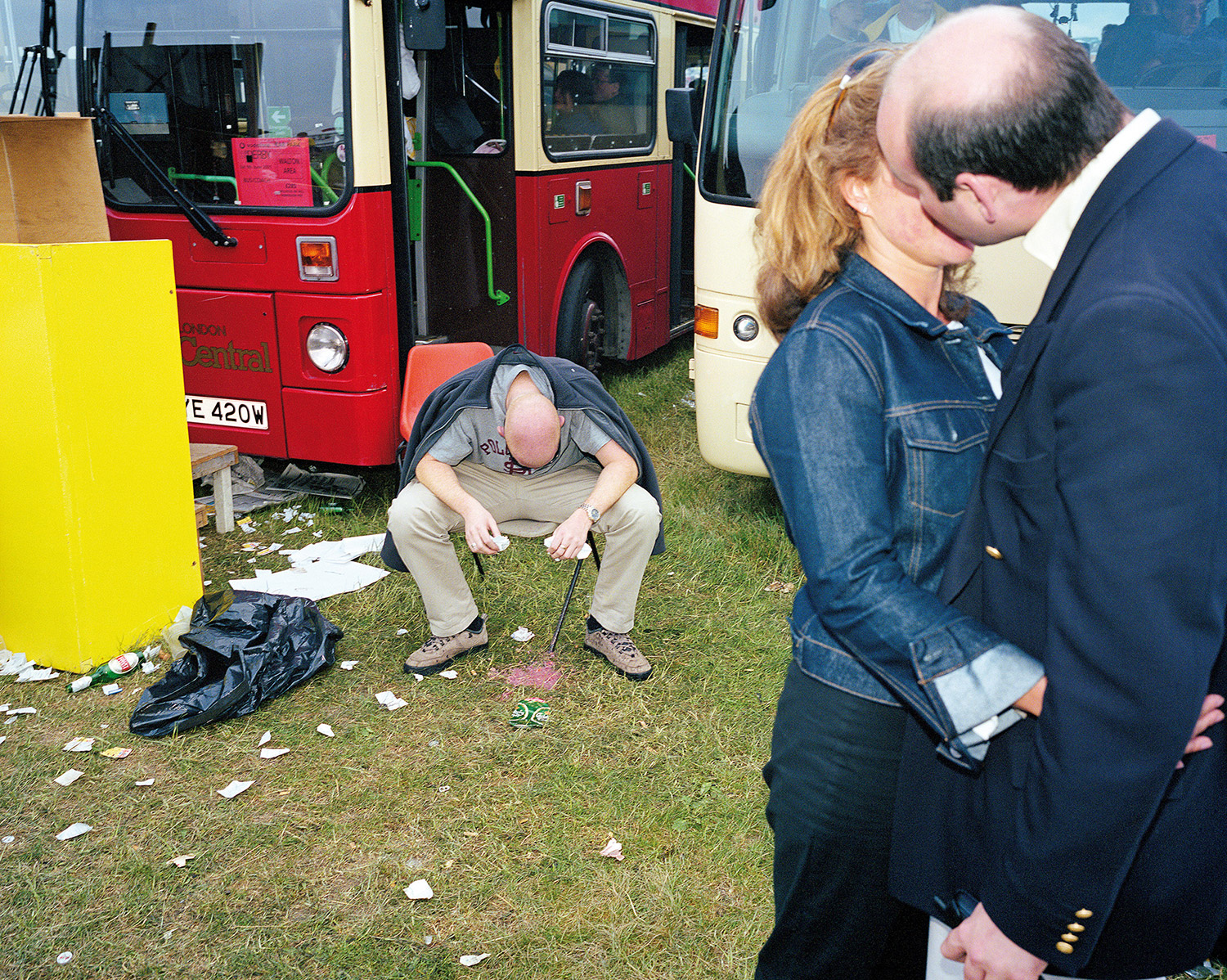

Nulla Dies Sine Alcohol

In the text about alcohol in England you ask a question — why do English people tipple until they fall down? Did you find the answer?

Maybe, the answer is we are a warrior nation, you know we’re an island, we’re invaders, we’re fighters. So when we’re not fighting other countries, because we can’t do that anymore, we just tend to fight ourselves, we are quite self-destructive. We tipple until we fall over, because we can, and because it’s what we’ve done for centuries. Those photographs are taken from 1998 to 2008, and I believe that in that time we were drinking younger, longer, more cheaply. since 2008, especially the younger generation, they seem healthier in their attitude. Statistics are conflicting, but from what I saw, they are more into fitness, when I did The British Abroad, I don’t know whether you agree, but people think the British man abroad — beer, belly, red skin, and that wasn’t the case. The young British abroad, the men were fit, they had tattoos, but they took care of themselves, you know they still drink too much, but there was a shift.

Did anyone of those drunken people in the picture had claimed you cannot publish them in the book?

I never say they are drunk, because I don’t know. I’m 99 percent sure when a person is drunk, but if you look at the captions in the book, you will never say a drunk man or a drunk woman because unless I’ve got medical proof, I can’t say that. I’m a photojournalist, so I have to be accurate.

Most people don’t mind being photographed, and they don’t mind seeing themselves photographed, I’ve never been successfully sued. The only time someone tried was the mother of someone in one of the pictures. The mother was embarrassed opening the newspaper on Sunday morning and seeing her 17-year-old daughter in a nightclub. The problem was that photograph was three years old, so you can understand why it’s been published now. I’ve never been physically attacked, just once, and that was because I was intervening in a domestic argument rather than taking someone’s pictures.

I think very carefully about which pictures to release into the world. There was one of a car crash, the driver died three hours after I took the pictures, I have many, but people can only see two, and I’ve decided not to identify him, you can’t see the face, and that was deliberate. I think quite hard about what to show. I don’t release picture until I know why I want people to see this picture. I take the picture, the next day check it out and give it to Getty. If anyone has a problem, they can always come to me and say — why did you take that picture? Why did you publish it? And I can say — this is right, there is the reason. In England you can still photograph people on the street, legally.

They don’t mind?

They mind more than they used to. People are more suspicious about where the picture is going to end up, and what it’s gonna be used for, but I always tell the truth: “Hello, I’m Peter Dench, I’m on assignment for the Sunday Times magazine and I’m photographing England’s relationship with alcohol.” And they can either go “I’d rather not” or “OK.” It’s a collaboration, I respect my subjects, even if they are in the gutter.

Do you have such things in your career that you would like to go back and change? Maybe you feel ashamed of something you did?

You can’t go back and edit your tweets. Once it’s out there, it’s done, deal with the consequences. This sounds smug, but I don’t think I would go back and change anything. My instinct says no, because I make sure I put myself in the company of people I trust: I’m talking about agencies, people who deal with me as a photographer. So if I weren’t a photographer, I’d probably be a rythmic gymnast. I’m lucky to be a photographer, it’s a privilege. Every other job I was handed I got sick from the fight, until the photography was the only thing left. You can travel the world, make people laugh, make people think and have a few drinks along the way, that’s not a bad way to live.

I know a lot of photographers, who are trying to do the same thing as they want their models to do — like, if they want to shoot models naked, they get naked too. Were you drunk all the way while you were shooting England drunk?

I was never drunk.

Were you drinking maybe?

Yeah. I drink a lot, every day. I haven’t had a day off this year. I rarely drink little, but I rarely drink too much. The reason I produce the book on alcohol in England is because when I was growing up, my parents worked for a brewery, so alcohol was around my life very early. I also grew up in that seaside town, a holiday town, so a lot of holiday makers, there was also a navy base, a lot of sailors — all drinking and fighting, and I thought this isn’t the England that you see in the brochures or on the adverts, so I wanted to put forward my interpretation.

If I pop into a pub, yeah, I’ll have a drink. I photographed wearing a pink wig, dressed as a schoolboy, naked, having few beers. Some photographers think that’s cheating, but I don’t see a problem.

Don’t you think alcohol is a problem? In Russia there’s a law that prohibits selling alcohol after 11 p.m. They are trying to fight alcoholism.

Governments have to be seen to be doing something, don’t they? It is a problem, if you see hospital emergency boards on a Saturday night, Sunday night, if you look at the liver disease statistics, it is a problem, it’s difficult for governments to manage. The British government tried many things, you know, raising prices for example, but you know, there’s so much money from advertising. It is and isn’t a problem.

Real England

What should you do when you get to England for the first time? How can you know what is England? Real England?

If you came to London for a start, you should go to watch football, then go and hang around outside Harrods, a store where there are a lot of arabs, communities, and a lot of wealth. If you gonna do a portray of a country, you have to do it diversely — both north, south, east and west. And socially — you know, rich to poor. So, you’d have to travel, you’d have to go and visit Blackpool, that will give you one version of what it’s like to be in England, but then maybe go to Royal Ascot or Henley Royal Regatta, and you’ll see another kind of side.

What is going on with photojournalism in England right now?

It’s tough. For ten years I worked for GQ magazine, Tatler, Marie Claire, Sunday Times magazine, Daily Telegraph magazine, there was a lot of work. You go and do your job, bring back later film, put it in the lab, the phone would ring and you’d go on another trip. That’s all gone. 95 percent of my income was from editorial photography until about 2009, and now it’s 5 percent. The tradition of reportage is gone. Ten years ago twelve pages in the Sunday Times magazine was what you aimed for, if you got five or six that was a bit of a failure, now you are lucky to get five. That market is gone. But there are other ways to get your work seen. These are very collaborative times, very exciting times. The photography can be very selfish, but now I think people are realizing, you need help, you look around, you can do video, you can do sound, you can write, it’s a lot more exciting. This has been my very successful year financially. But for young photojournalists it’s very tough. Agencies have closed, newspapers are disappearing — in England, I can’t say for elsewhere. But I don’t want this to be depressing, I think people just have to be proactive and shifting in that perspective and choosing how to get their work seen and how to try to monetize that. So it’s challenging at the moment.

You are friends with Martin Parr, right? I saw him last year at Paris Photo, he looked tired and bored, is it true, is he bored of photo?

No, we are not friends. We know each other; I’ve been to his house twice, once as a young photographer to show him my work. I’ve never had a drink with him, but I have taken him a cake. He is a tea drinker, essentially. I don’t think that he is tired. If you see how many books are coming out, he also curates exhibitions. I was once called ‘the affordable Martin Parr’, ‘Martin Parr’s drunken brother’. People often ask me do I mind the comparison with him, and I don’t. It’s impossible to photograph England in color without that happening, and he was an early influence. His work in New Brighton. The Last Resort showed me that as a photojournalist you didn’t have to get on the airplane and go to the frontline of a foreign war — you could just go to the pub or the supermarket, and for me that was a revelation, because I never wanted to do that — that frontline.

What is your main aim as a photojournalist?

That changes from day to day (laughs). Just to leave an anthropological legacy of what I think is the truth and what I think might matter. You know, just a little contribution. Alcohol and England, I think, that’s a piece of history. Then there’s The British Abroad, maybe cheap holidays, cheap flights will end one day, and we will look back at this set of pictures and say — that’s the defining visual truth or reportage on that piece of life during that time. I just want to be entertained and I want to entertain. If you can effect change and get people to at least consider your point of view, then for me that’s a success.

(Cover photo: from Alcohol & England project)