I’m Afraid I Will Make More Strong Images of War: Pulitzer Finalist Wissam Nassar on Gaza Strip

Palestinian photojournalist, was born and lives in the Gaza Strip. Covers the Israeli–Palestinian conflict for international agencies. His images are published in The New York Times, Al-Jazeera, The Times UK, Focus (Germany), Xinhua, and many other outlets. 2015 Pulitzer Prize Finalist in Breaking News Photography. Currently, works on the project about the after war life in Gaza and the smugglers’ tunnels on the Gaza–Egypt border for the Time magazine (US).

I am a Palestinian refugee living in the Gaza Strip. I was born soon before the first intifada and I’ve always been surrounded by the evidence of war. Despite coming from an extended family, I’m one of eight siblings; my parents still insisted on getting an education so I went to a UNRWA school for refugees. When I studied at school if somebody from our neighborhood was killed we all left classes and ran to watch the scene. This is my generation’s childhood. That’s how we grew up.

I studied journalism at the Islamic University of Gaza which was destroyed during the Israeli Operation Cast Lead in 2008. I attended Reuters’ mission masterclasses and was lucky so many great international photojournalists came to work in Gaza and were ready to help and to teach. I benefited from their experience and knowledge a lot. But the best teacher was the Gaza Strip itself. I still remember how my father bought me my first camera and how proud he was. I chose photography because of the things I saw and the world I lived in.

My family is a family of refugees. Without permission, we cannot go to the occupied Palestinian territories that are called Israel. There are so many unfair restrictions for Palestinians that touch even international organizations working here. It’s a collective punishment. The Gaza Strip is an open air prison living under the Israeli blockade for years. This made Palestinians dependent on aid. This made them refugees in their own land.

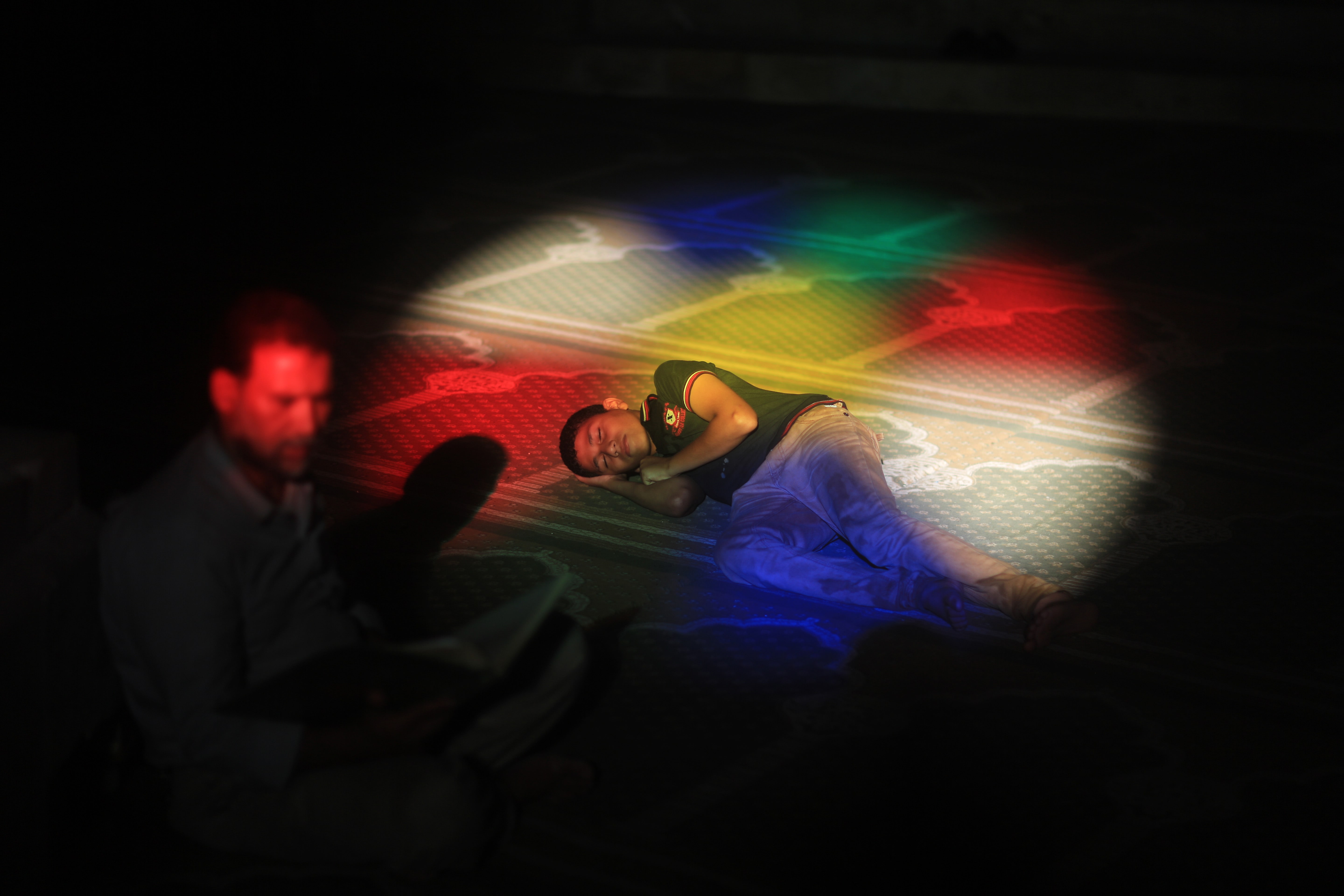

The current situation in the Gaza Strip makes you stuck on the themes of death, violence, despair, but this is, unfortunately, the routine of life here. I’m trying to break it photographing artists, graffiti, and people resting and having fun on the Gaza Beach that is kept under the Israeli siege. I try to show how Palestinians challenge these hard circumstances.

Seeing violence with my own eyes is much harder than through the lenses of my camera. When I see blood and body parts on the ground I use my camera and take a humanitarian shot that will move the audience but not throw it into horror.

The threat is unrelenting. And that is the hardest in my work — being constantly unsafe myself and having fear for the life of my family members during the airstrikes and the shellings — there were times when they were located in that same area I was covering. But also those were the times when I made the strongest images, during the three wars in 2008, 2012 and 2014. I expect to make more terrible war images — that’s the most frightening. But to take people from around the world into the Gaza Strip, that is my task.

I never worked for Hamas or Fatah. I work for international magazines and organizations and I do respect their laws on the objectiveness of photojournalism. And if I ever cross this line of objectiveness I will be never allowed by Israel to work in other countries. And the best proof of my objectiveness is that my images are criticized by Hamas and Fatah both. If the situation is harsh and I am demanded to take a side I rather leave the field to save my objectivity than to keep working knowing that my images will be used for propaganda. I will do my best so that biased photos would not be published. Life is complicated and sometimes it’s not that easy to stay totally independent and avoid any pressure. I try to be in good relations with the citizens of any country. But I personally cannot have Israeli friends because Hamas doesn’t forgive such things.

Nowadays, I can’t visit any country because Israel does not issue a permit for me to leave Gaza. I think that traveling is important not only for discovering the world and the differences but also it helps to measure how much support there is for Palestine against Israel. For me, it is a rest for my eyes from the blood. Going out of the Gaza Strip helps me to stay optimistic.

My wife is Egyptian and she and my son spend most of the time in Egypt and frankly she can’t bear this violence in Gaza. I can work there, I have a house in Egypt and a shoe business that will keep my family, I can move to a safer place and I want my son to attend a British school in Egypt and live a safe life. My little son already asked me: “Why is the power cut? When we were in Egypt I could watch TV anytime but in Gaza, I can’t.” I don’t want my son to have such a hard experience as I had.

I love Gaza. But I feel frustrated. I’ve been seeing this all my life and photographing for almost half of it. I have to stay even in the hardest time, that’s my job. And if someday I will have to leave Gaza I will not work in the field of photojournalism anymore.

New and best