Alice from Wonderland, Faraday,

and a Danish Prince in Lewis Carroll’s Photographs

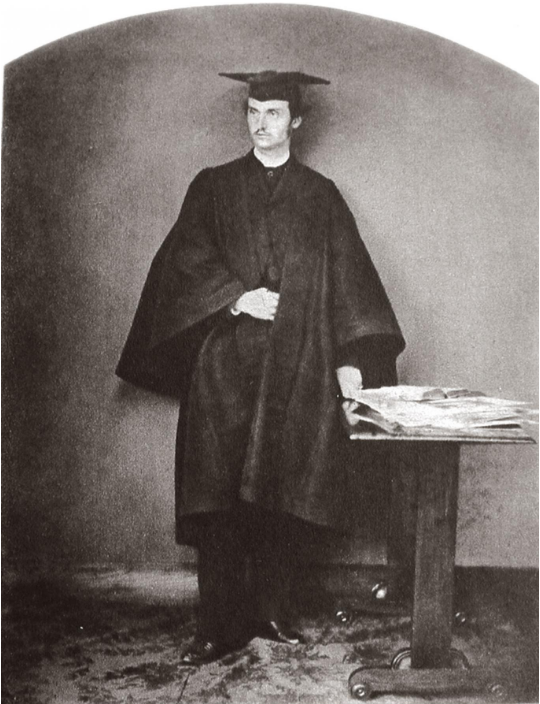

Lewis Carroll

(January 27, 1832 — January 14, 1898, real name: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) English writer, mathematician, logician, philosopher, deacon, and photographer.

Carroll was very fond of gadgets: he was one of the first to start using a typewriter in his work, rode trains and bicycles soon after they were invented, and tested the first phonographs. He became fond of photography in 1856, soon after he bought his first camera in London (it cost 15 pounds — which was a significant amount for a 24-year-old math teacher). Since then, he almost never parted with it.

In the same 1856, Dodgson met and made friends with the family of Henry Liddell, Dean of one of the Oxford’s colleges. During their joint walks, the future writer entertained 4-year-old Alice and her sisters Lorina and Edith with stories about the adventures of a little girl named Alice that he made up on the spot. Later, it was Alice Liddell who convinced him to publish these stories as a book (in 1926, she will sell a handwritten copy of the book that Carroll gave her for 15,400 pounds to pay her debts).

Alice Liddell in the photographs by Lewis Carroll in 1860 (L) and 1858 (R, dressed as a beggar). Photo: wikimedia.org

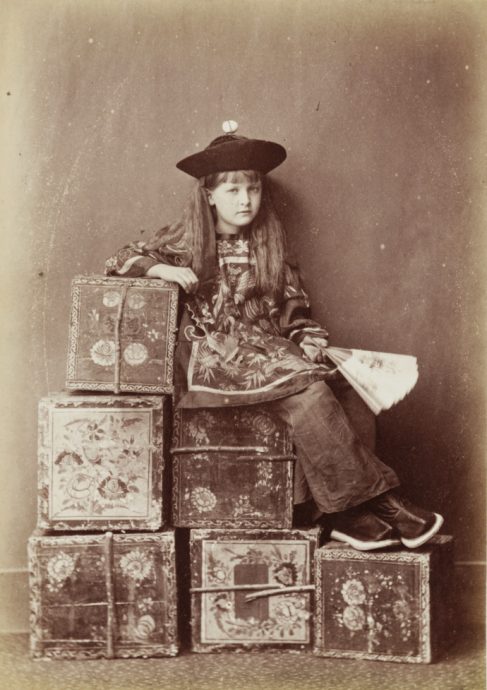

Carroll would often take pictures of Alice and her sisters. Many of the images have lived to this day: here the girl is ceremoniously standing next to a flower pot wearing a white dress, in the other photo she is standing barefoot dressed as a beggar, in the third one she is wearing a Chinese costume… After the shoot, Carroll allowed his model watch how he developed film (she will recall later that this was much more interesting than posing for pictures). The last picture of Alice, who was 18 at the time, the writer took in 1870.

Alice, Lorina, Harry, and Edith Liddell, a photo by Lewis Carroll. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London / National Media Museum

Edith, Lorina, and Edith Liddell, a photo by Lewis Carroll. Photo: wikimedia.org

Alice was not Carroll’s only model. For many years he thought that photography was the main occupation of his life, and teaching was just a tiresome inevitability (his students will later say that he was a very boring lecturer and seemed to have never smiled in all his years of teaching). Carroll spent his workday as follows: he taught classes in the morning and spent evenings preparing for them, while his afternoons were busy with shooting, developing film, recruiting models and creating costumes — he borrowed some of the clothes from the theater, but some of them he created himself.

When, in 1868, he moved to his own apartment, the first thing he did was build a photo studio in his attic. Carroll even traveled with his camera, sending all the equipment by train in advance.

Alexandra 'Xie' Kitchin dressed as a Chinese tea merchant, circa 1876, a photo by Lewis Carroll. Photo: National Media Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Portraits became his favorite genre. He managed to make the photographs look effortless and natural, which was untypical for his time. Carroll’s lens caught everyone: friends, relatives, children, colleagues from Oxford.

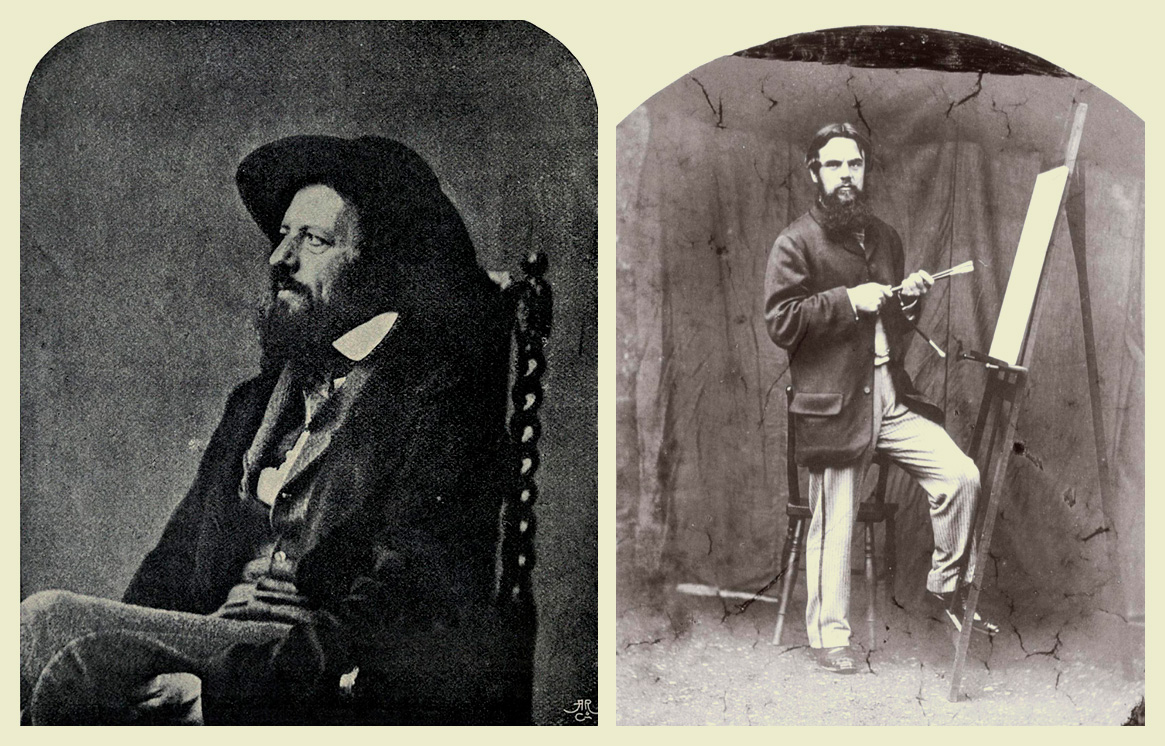

He was usually modest and shy, but became extremely persistent when it came to photography. For instance, when he decided that he needed to take a photo of Alfred Tennyson, he traveled to Lake District and visited him without an invitation (which was considered extremely impudent in Victorian England). The poet wasn’t home, and Carroll kept calling until he finally met Tennyson and got the opportunity to take his portrait. “Wilfred must have basely misrepresented me if he said that I followed the Laureate down to his retreat,” he later justified himself in a letter to his cousin. “Being there, I had the inalienable right of a freeborn Briton to make a morning call.”

Photographs by Lewis Carroll. On the left — poet Alfred Tennyson (photo from The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, by Stuart Dodgson Collingwood; on the right — painter William Holman Hunt, 1860 (Photo: Princeton University Library)

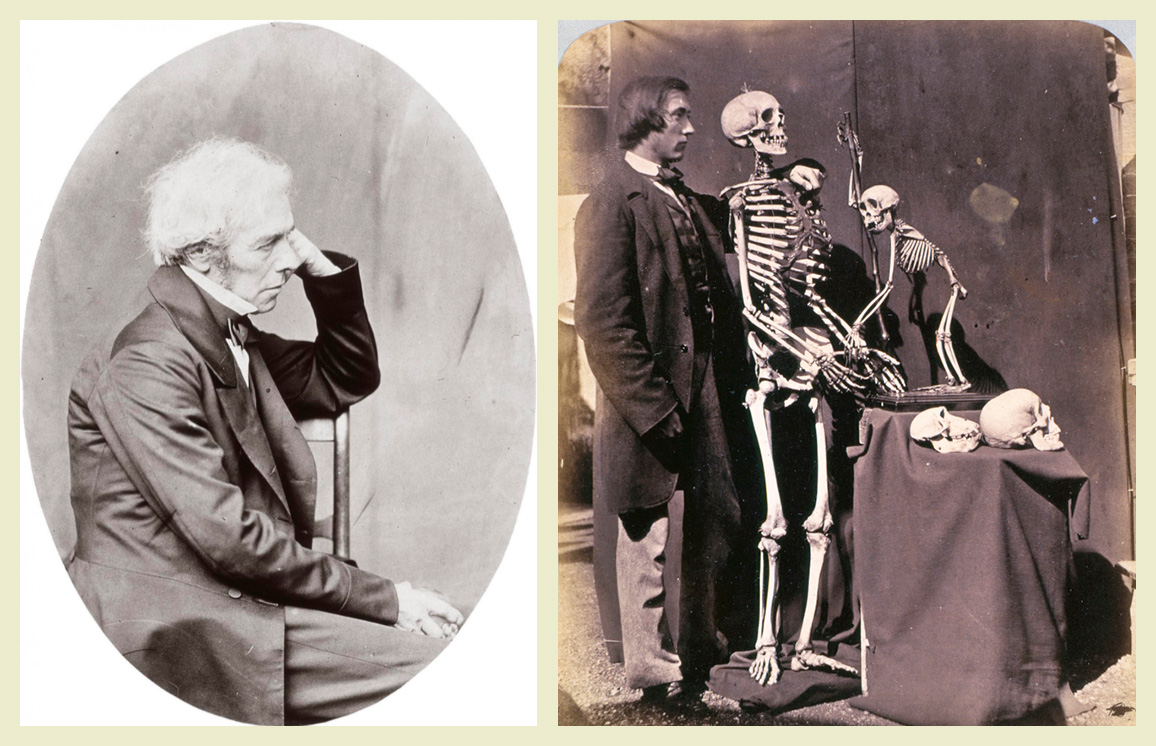

His attempts to photograph the royals were even more persistent. He had been trying through third parties to obtain permission to take a picture of Queen Victoria for many years, and as soon as he was introduced to the Prince of Wales, he tried to convince him to pose for a portrait. The Prince, who was rather tired of photographers, managed to escape. So, a Danish Crown Prince became Carroll’s most aristocratic ‘trophy’. He was much luckier with scientists: for instance, Carroll took photographs of Thomas Huxley and Michael Faraday.

Photographs by Lewis Carroll. On the left — physicist Michael Faraday, 1860 (Photo: Princeton University Library); on the right — doctor and inventor Reginald Southey with skeletons and skulls, in the late 1850s (Photo: National Media Museum / Science & Society Picture Library)

Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark (future Frederik VIII), 1863, a photo by Lewis Carroll. Photo: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

New and best