Stanley Greene: “I Actually Like Being Alive, It’s a Great Experience. Everyone Should Try It.”

There is no photojournalist who would not know Stanley Greene. Winner of five World Press Photo awards, one of the founders of NOOR photo agency, author of the Black Passport — one of the strongest examples of the author’s narrative about war — he witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the storming of the White House in Moscow, covered military conflicts all over the world, including the Chechen War in Russia, conflicts in Georgia, Iraq, Somalia, and Lebanon.

Stanley Greene was born in New York. His mother was an actress, his father was a director and actor in theater. Stanley got his first camera as a gift from his parents when he was 11. At 22, while being a member of the Black Panthers, he entered the School of Visual Arts in NYC on the recommendation by Eugene Smith. Early in his career Greene documented the life of local rock bands. In 1986, he moved to Paris where he started working for fashion magazines. Working as a fashion photographer was boring, and Greene, in his own confession, relieved the boredom with prostitutes and heroin.

Stanley Greene’s career in photojournalism started with the fall of the Berlin Wall. His photograph of a young woman climbing over the wall in a tutu with a bottle of champagne became symbolic.

“Stanley and I met in the jury of SlovakPressPhoto. I was impressed with how quickly he was sorting through the contest submissions and finding the worthy ones immediately,” Ukrainian photographer Alexander Chekmenev says. “After I presented my series about Donbass at the festival, Stanley approached me and hugged me. This was more than a praise.”

“I first met Stanley in 2011, at the NOOR-Nikon masterclass,” photographer Arthur Bondar says. “Stanley had a very powerful charisma. He combined the qualities of a showman and a photographer in a unique way. He told us a story that forever changed my attitude not just to photography, but to the world. One time Stanley came to Eugene Smith’s studio with a brand-new camera in a case that still had the smell of leather. Eugene Smith took the camera, took the case off and threw it into the garbage. After that he took out a huge nail and hammered it into his wooden table with the camera. And then handed it back to the dumbfounded Stanley and said: “Remember, a camera is just an instrument.”

Last year, Bird In Flight photo editor Olga Osipova met and interviewed Greene at the photo festival in Perpignan. We illustrated the interview with the photographs from his latest project, Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia, which documents the life of Russians in the ‘empire’ of their president, from Kursk to Sakhalin.

“Before we start, you should watch this video,” Stanley says and hands me earphones. We are sitting on the second floor of the Palace of Congress in Perpignan. During the annual photojournalism festival, it houses stands of the most famous photo agencies of the world. Young photographers are queuing up to many of them, looking to show their work to renown colleagues. It’s busy. Stanley is traditionally wearing his round sunglasses and a bandana and is unfazed. Photographs flicker on his phone screen accompanied by suspenseful music: protests, wars, blood, scalps, disorder, wailing children, screaming women, and men shooting.

— The point of this video is to show that our agency [NOOR] is hardcore. Our niche is to document the unseen, the truth, what is the hidden truth in the dark. I am trying to bring the agency back to that kind of thinking, kicking and screaming all the way, of course. We got comfortable, and I am trying to find a way to upset people, enough so that they want to be angry about it.

— Do you want the photographers to be angry?

— Yes, because I think it is important that we do these stories. I don’t think that everyone should do them, but there should be somebody who goes out there and makes a visual statement about how screwed up everything is.

— Do you think photography really could change something in the world? Do you have any examples?

— If you can point your eye on something, use your camera like a scalpel. If you don’t try, you’ll never know. But I do know.

— Do you have an example of any of your pictures changing something?

— I am not so sure any of my pictures have changed much. But I would say that my pictures of Chechnya made people see it with a human face — not like terrorism, jihad, and so on and so forth. They gave a sense of why people are so pissed off. And that in itself is important. Getting the work out there, showing your work, speaking about your work can make a difference.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. A miner. Prokopyevsk, Siberia, 1998.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. XYZ generation in front of Gostiny Dvor in St. Petersburg, 2001

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. The white plague in the Siberian colonies. Novokuznetsk, 2001.

— You worked in Chechnya with Anna Politkovskaya, right?

— Yeah, we were friends.

— Do you think we can protect journalists from violence?

— No. We used to. There used to be some kind of unwritten rules. There is an episode in The Untouchables where a journalist is killed, and a big mafia boss says: “What are you, crazy? You don’t kill journalists.”

— Yesterday there was a presentation of the book about the Black Panthers. And I thought that we know you as a photographer, but we do not know much about you as a teenager being with the Black Panthers.

— I was political. My father was a Communist, he was even blacklisted during the witch-hunt. He believed in being a family man, he believed in being a man. He was not religious. So, I grew up in that environment, I was a member of various political organizations. I started my own anti-war organization called Peace of Mind. So, it was a natural transition for me to slip into becoming a Panther, which was very interesting for me. Then, when I was in Ypsilanti, Michigan, I was involved with the Panthers again, on a more of an adult footing. So, I had two periods with them, one when I was a youth, and one when I was much older.

And the problem that I always had with the Panthers is that they became so disoriented and so disruptive. Provocateurs had infiltrated them and set one against another, which was causing conflict within the confines of the organization. George Jackson was shot dead by the prison guards during the attempted escape in 1971. And one of my mentors died in a bank robbery.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. Liudmila is fishing on ice to feed her family. Tretya Pad village, Sakhalin, 2002.

— When you see some kind of injustice, do you feel like you should fight it?

— Honestly speaking, somebody has to be the bad guy, and nobody wants to be the bad guy. Americans, when they were in Iraq, they should have leveled some of the cities to the ground. Because suicide attacks began, and everything was totally screwed up. But if the Army was harder on them, they would have joined together and they would have seen us, the American military, as the common enemy, and all those innocents who got caught up in the middle wouldn’t have been cut to pieces. The Army went half way, but they had to pull it all the way. If you gonna go in and be the so-called ‘protector of the world’, you have to be ready to step up to the plate.

You see situations where people — innocents, children, handicapped, women — were used as part of the arsenal of military or of rebels. Individuals who get away with murdering journalists, get away with murdering an NGO personage, and nobody calls them out on it. It’s bullshit. When we get to a point where we have a demagogue like Trump even being discussed as presidential candidate, even this fact is incredulous. How is that possible that we are having even a discussion on this subject. The man is not presidential material, he is a demagogue, a racist, and he makes me sick.

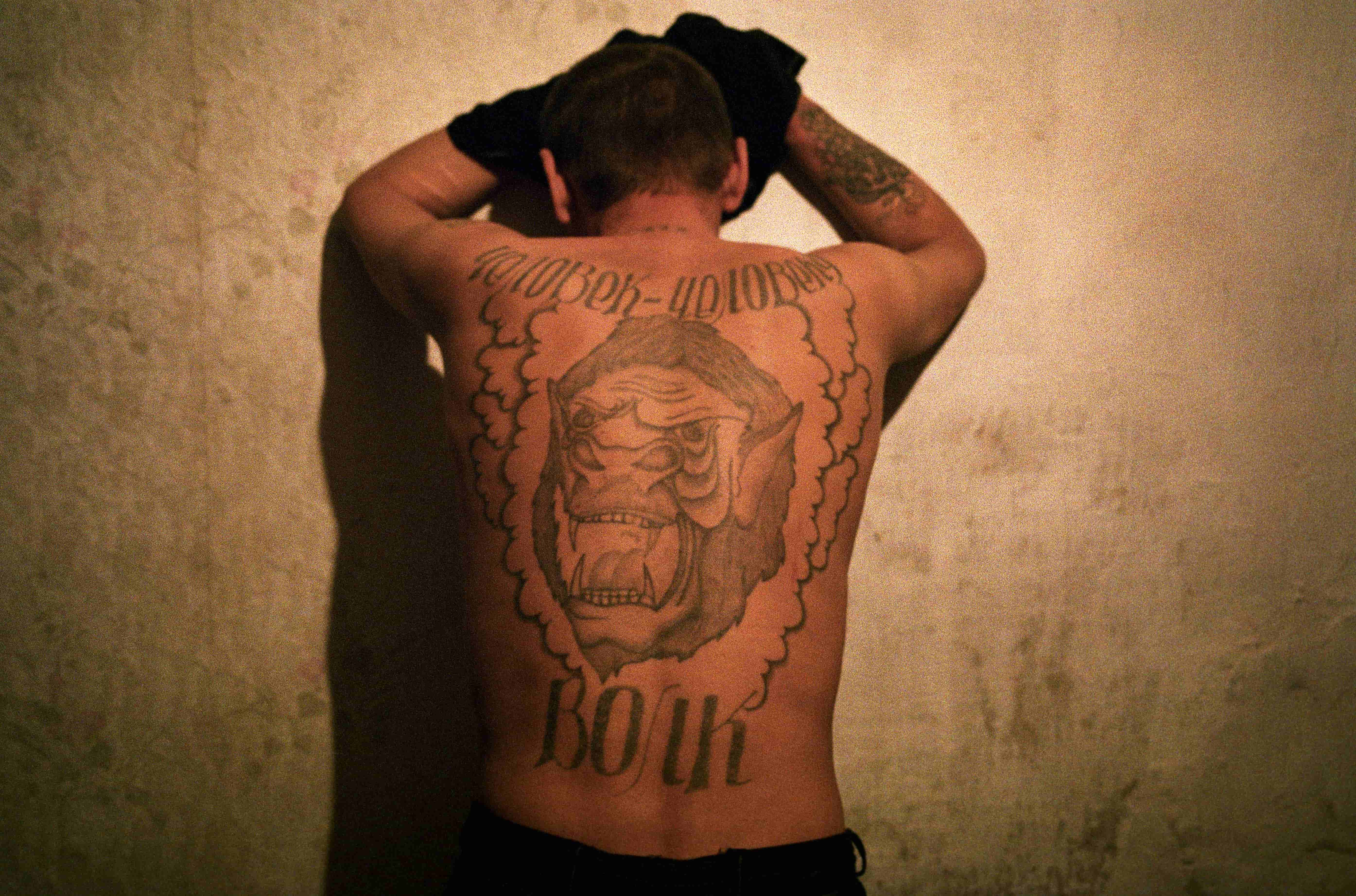

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. Volodya, or ‘Wolf’, went to prison twice for stealing and for the illegal possession of a gun. Rybachi village near Vladivostok, 2002.

— You once said that in childhood you saw the world in black-and-white. Why?

— Because I saw WWII in black-and-white. I saw the photos, and I always thought Nazis should be in black-and-white. I saw the Vietnam War in color.

— You witnessed the breakup of the Soviet Union. I know what the Soviet people felt, but I don’t know what an American could feel.

— My problem with it is that we didn’t do our homework. We never took on board the hostility that was percolating underneath the surface. And therefore, when it came down, all of that hostility just bubbled up in such a dramatic way, and it was so horrific and terrible that we never recovered from that. We are now recovering from that. And it’s still going on and on. We always spoke in America about the domino effect. That was the domino effect, one [country] right after another, and another, and another. I think about all the innocent people that have been killed behind that idea, that ideal, and I think that’s criminal.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. Junkies being high in an apartment in Russia, 2001.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. The OMON, a special purpose police unit, searches the apartment of the drug addicts. Volgograd, 2001.

— The Russian youth were recently surveyed about the putsch, and almost 50% of the respondents said they didn’t know anything about it.

— They covered it up. They covered up that a thousand people were killed in a horrific way, if not more. War is always horrific, violence is always horrific. And nobody gave a shit. They said: “Get this fixed, Yeltsin. You are our boy, you are a democratic candidate.” And Yeltsin sent his tanks. Because I mean, let’s face it, when Russia needs to make a point, they are sending tanks. All through history they are sending tanks. And that’s a tragedy for me. That we allow governments to do these kind of acts against people. And the Americans are just as bad in that.

— Do you think we could change it somehow?

— I used to think so. I think that the solution for Russia is that the Russian people should rise up and say that enough is enough. But I don’t see how they are going to do that.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. A night club in Moscow, 2003.

— Which of your trips was the worst and why?

— Rwanda. Because of all those bodies. You are photographing, and all you see for miles, and miles, and miles are bodies. And you are standing there and photographing those miles of bodies. That smell stays with you.

— I have a lot of friends who are war correspondents, and they also always tell me about the smell of the bodies.

— There is no smell like this in the world, and once you smell it, it never goes away. It’s always lurking.

— Can you have a normal life when you are a photojournalist?

— I would like to believe you can. Unfortunately, I am not a very good poster child for that, I don’t seem to be too successful in having a normal life. I’ve been married twice. It’s all about how much you’re willing to get back to it, and in the end, you get back too much or too little. There is an anxiousness about not covering certain events and not being there. You try to fight it, cause it’s like a disease, and you don’t want to get too sick.

— Do memories come back to you in your dreams?

— Dreams? I have nightmares. Not the war — just the questions and the doubts that you have about yourself as a human being. I am on this mission to try to be a better human being. I try to be a good guy. But I am still the bad guy. And when I was younger, I was a super-bad kid. I was the kid my parents told me to stay away from.

— What did you do?

— I sold drugs, for example.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. A view of Moscow, 1998.

— Are you scared of anything?

— Scared? Somebody once said that courage is the control of fear. If I am scared of anything, I am scared of being seen as… I was with a friend the other night, and somebody said: “You’re a f*cking asshole.” And this friend got so upset, and he asked: “Am I an asshole?” And I said: “Yeah, you’re an asshole.” I said I was kidding, but we’re not talking to each other now. So, you have to be careful about what you say to people. You can’t say somebody’s an asshole or ‘f*ck off’. When I was younger I was very quick to say ‘f*ck off’.

— What would you never shoot?

— Execution. Somebody getting their brains blown out on camera. It’s not that I don’t want to, I just don’t see how I could. It’s like underwater photography, you need certain skills to do that. So, that’s an issue.

— Did you ever think about changing your profession?

— Yeah, actually, I thought about it for about two seconds. Actually, I wanted to be a musician. I saw Jimi Hendrix play, and he played so good, and I figured I was never going to cut him. That was really depressing.

— Can you play the guitar?

— Yeah, I practiced and practiced, and still not good enough. So now I am giving up. Now I am trying to find my tools.

— How do you see yourself in ten years?

— Dead. Or not dead.

— That’s optimistic.

— It’s reality. I am 67. Hopefully, I am alive. I would like to be alive. I actually like it. I think it’s a great experience. Everyone should try it.

From Putin’s Russia — The Darkness of Russia series. An area in Penza oblast in Russia that is radioactive due to Chernobyl nuclear accident. Russia, 2001.

Photos: Stanley Greene / NOOR

Cover photo: Jerome Delay / AP Photo

New and best