Yurko Dyachyshyn:

“My Lviv Is Already History”

Born and lives in Lviv. Works on personal documentary and art projects, among them Slavik’s Fashion, Slavik Super Star, His Dreams, Carpathian Shepherds, Benches, and Saint Franklin. Has been documenting street life in Lviv since 2003. Had personal and group exhibitions in Ukraine, Russia, Poland, Australia, and Cambodia. Winner and finalist of various photography contests. His works are in private collections in many countries around the world.

— I first got interested in photography in 2002. At the time, the Internet has not yet penetrated our lives as deeply as it has now: there was not much information available and it was not as easy to get it. It took me years to do something that it takes modern youth several months to do. There were no photographers you could study from or who would point you in the right direction. Of course, you can’t avoid making mistakes when you were young, but you can never turn back time. And nonetheless, I also have some good memories about those times. Especially the Dzyga art group and Vlodko Kaufman who helped me find my way as a young artist.

— One of your first personal exhibitions was called Life Is Beautiful. Is this still the way that you see the world?

— I am afraid that people now only remember the name, but not the work that was exhibited there. There were many photographs of marginalized people in that exhibition — it was my first attempt to say that you need to value what you have. After that exhibition, I became known as a ‘social’ photographer, although it is not entirely true. At the time, I was a rather romantic person, but with time, romanticism goes away, and cynicism finds more and more ground. You have to ‘save the world’ in a different way, or just observe the natural selection.

— Tell me how you work with people. Are you interested in who they are?

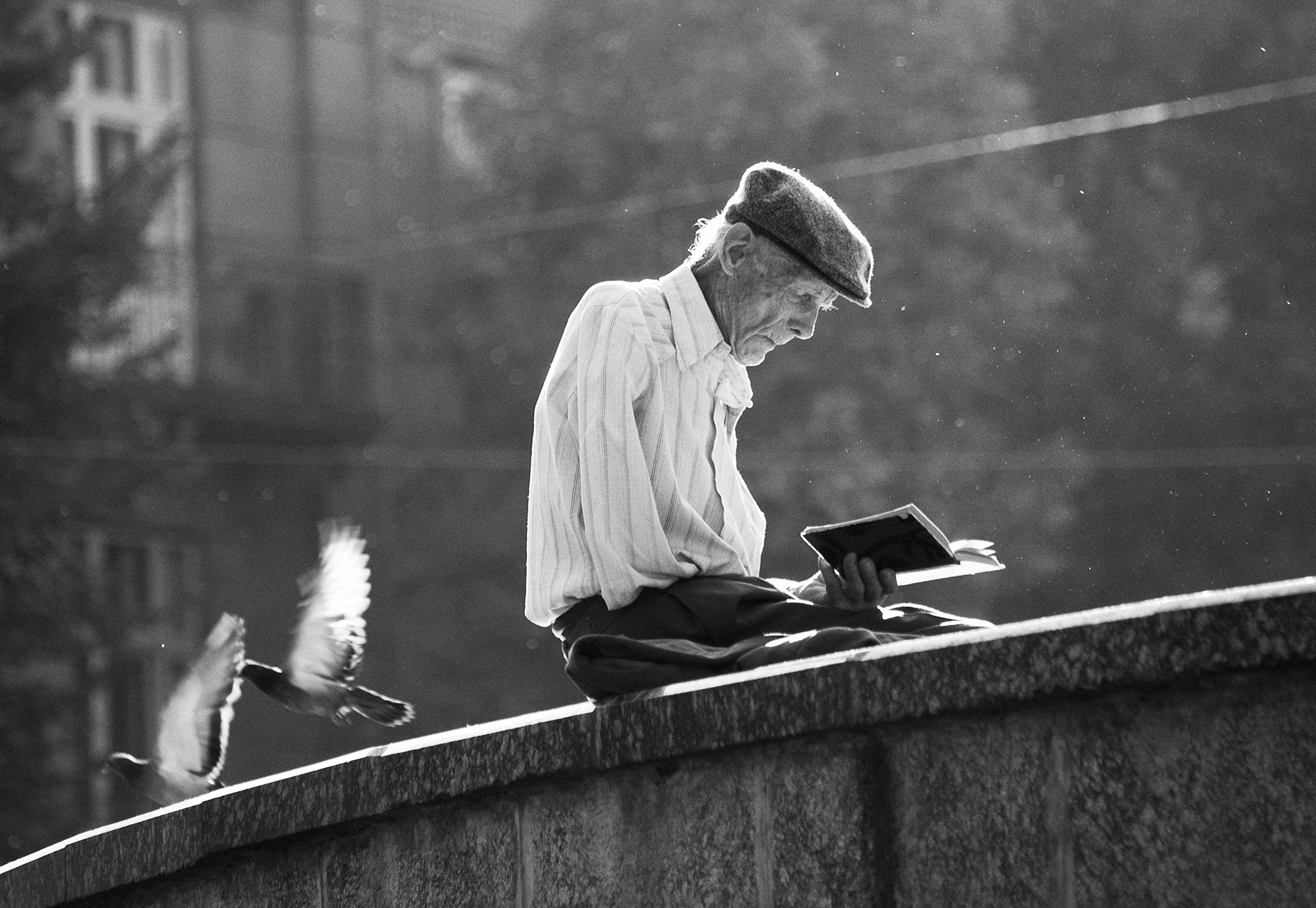

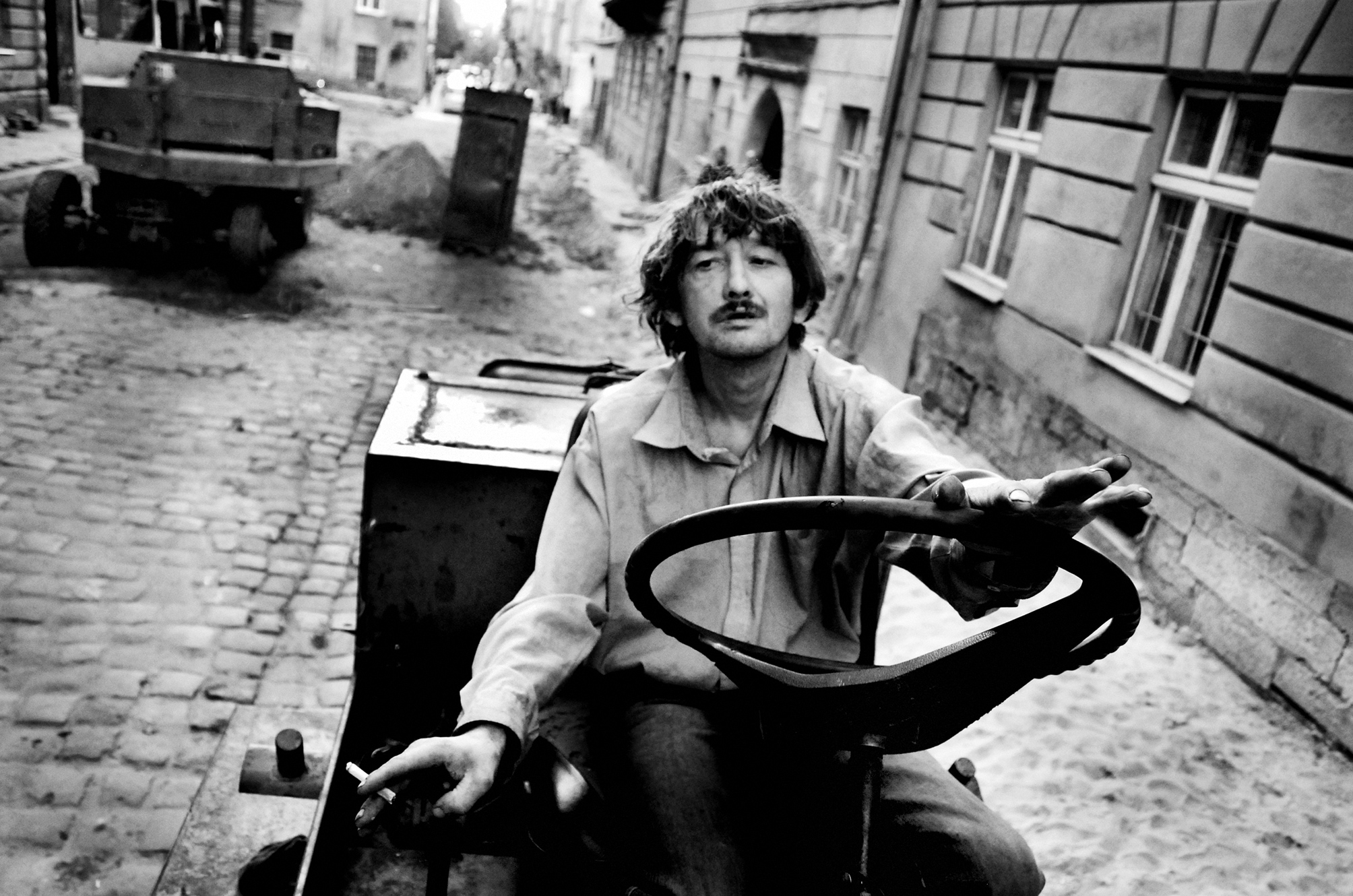

— Very often, people in my photographs are weirdos or crazy — random people whom I meet in the streets of downtown Lviv. It is impossible to maintain a relationship with them in the usual understanding of this word. But I am trying to find out everything that I can about them and follow their lives. I am always honest with them and I always tell them what I am taking their photographs for. I am not trying to influence their lives in some way or to change them: I am not a social worker, but an artist, who has other goals and tasks, and obligations to humanity.

— You spent several years on His Dreams, a project about a Lviv social outcast named Andriy. How did you get interested in that person?

— Indeed, I spent over eight years on His Dreams. It is a multi-level project in terms of senses and messages that I attributed to it as I was working on it. It was both a documentary and a theater piece, but at the same time, it wasn’t a documentary project about another complicated story of a certain person, it was about something different. What exactly? A story about dreams, observation of a sacrifice, a tale of fears and ghosts — basically, it was about each of us.

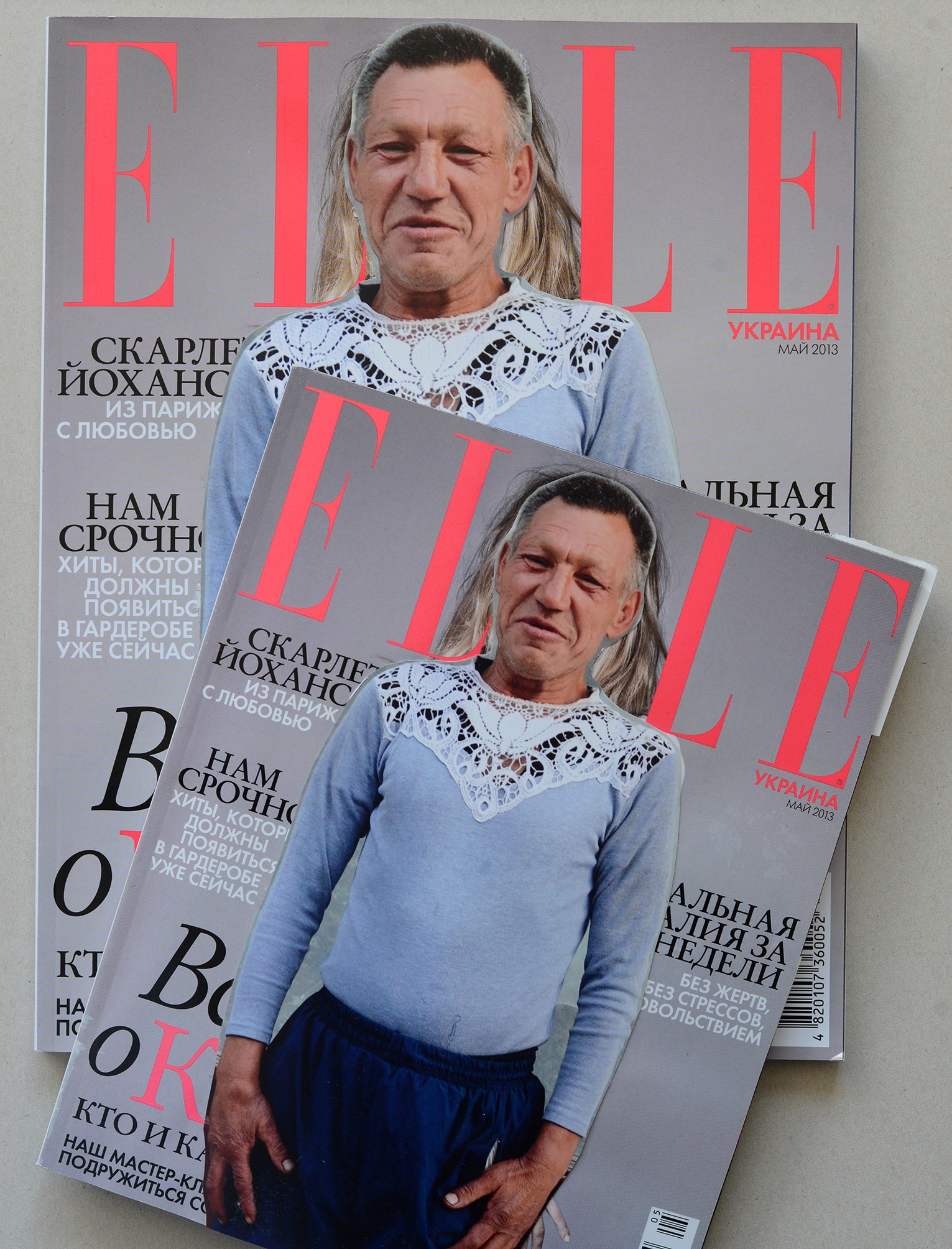

— You are also the author of Slavik’s Fashion. Who is this Slavik? Has he seen your photographs?

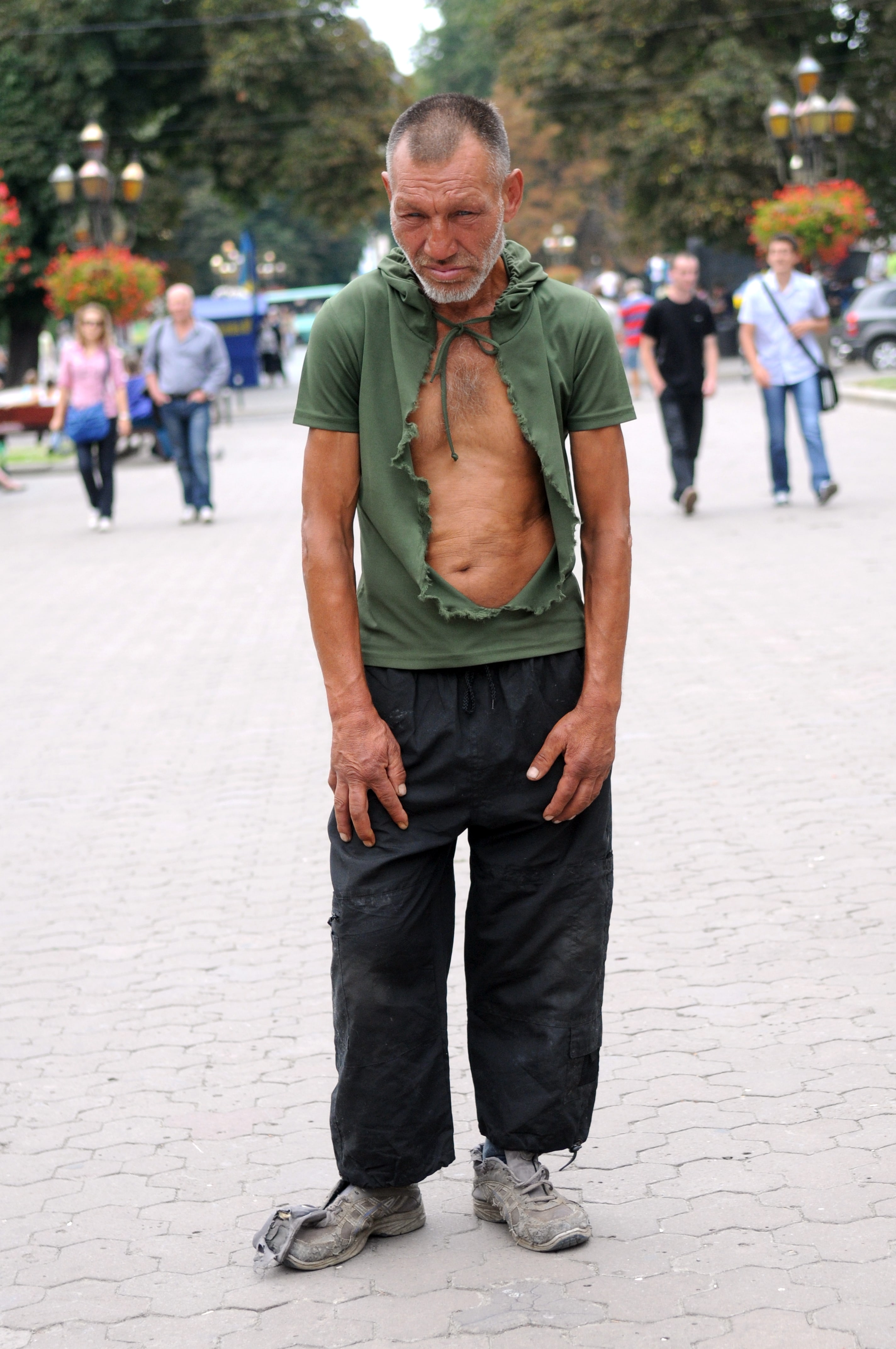

— Slavik was 55. He was a homeless eccentric tramp, a Roma, but a very different one. He led a distinctive way of life, absolutely not typical for this kind of people. Slavik never carried around numerous bags, did not pick the trash cans, and did not communicate with the other homeless people.

He almost never had the same outfit on, which is very strange, and obviously, very difficult for a person with no roof over his head. In addition to the everyday change of clothes — sometimes even two changes a day — Slavik regularly changed his hair, his beard, and even shaved his armpits. How can a homeless person do that at all? He wandered the streets all the time, begging selectively and gently. He regularly drank alcohol, mostly beer, but he was not an alcoholic.

All of the photographs — over a hundred portraits — were taken during our accidental encounters in the course of two years. I could meet him every day, or see him once in several weeks or months. He enjoyed posing: I think, there was a reason that he wore costumes. It was his endless performance, and the fact that people paid attention to him was pleasant for him and made him happy. I printed the photographs for Slavik several times, and he was very glad about it. Slavik was the most fashionable homeless person in the world. Unfortunately, in 2013, he disappeared from the streets of Lviv.

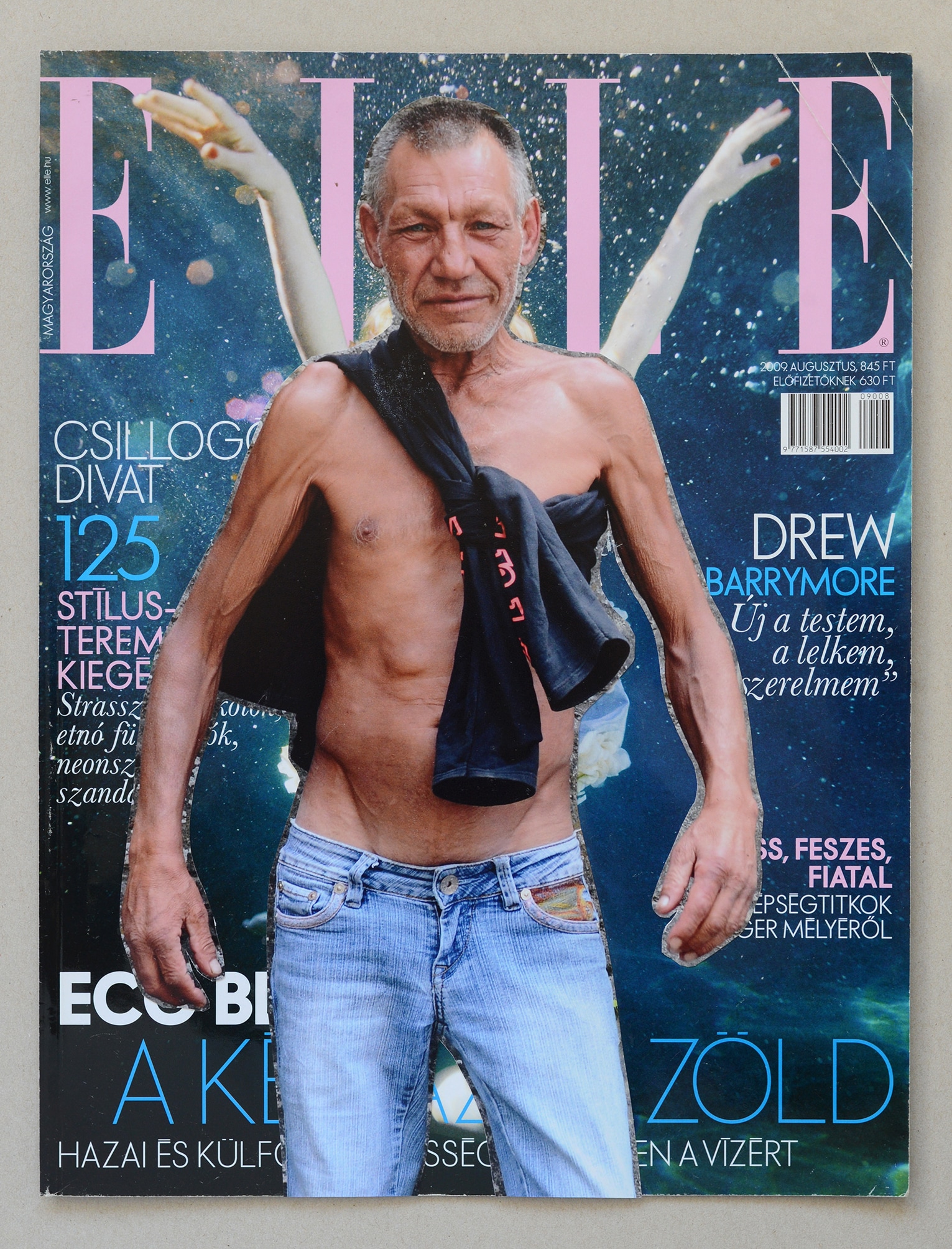

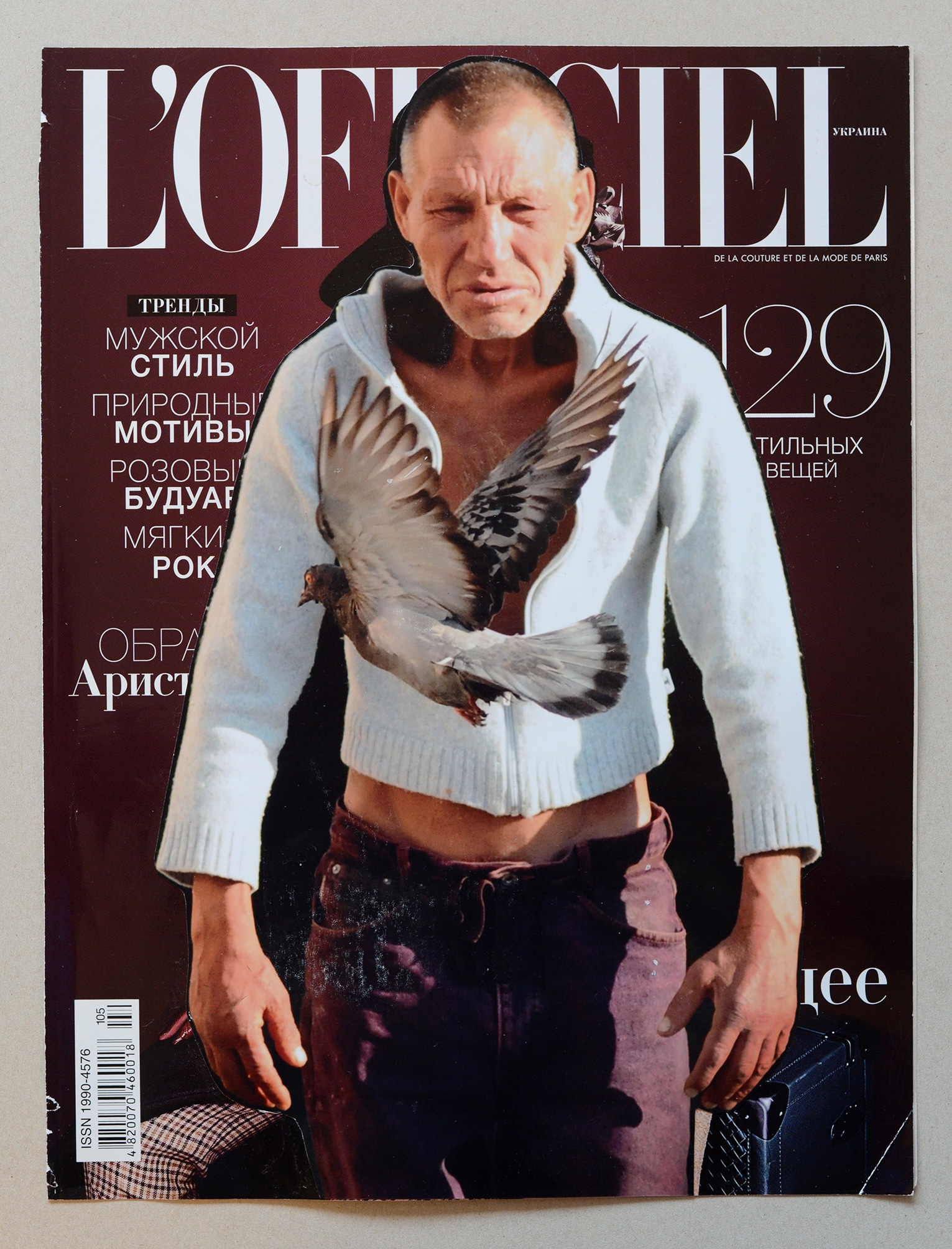

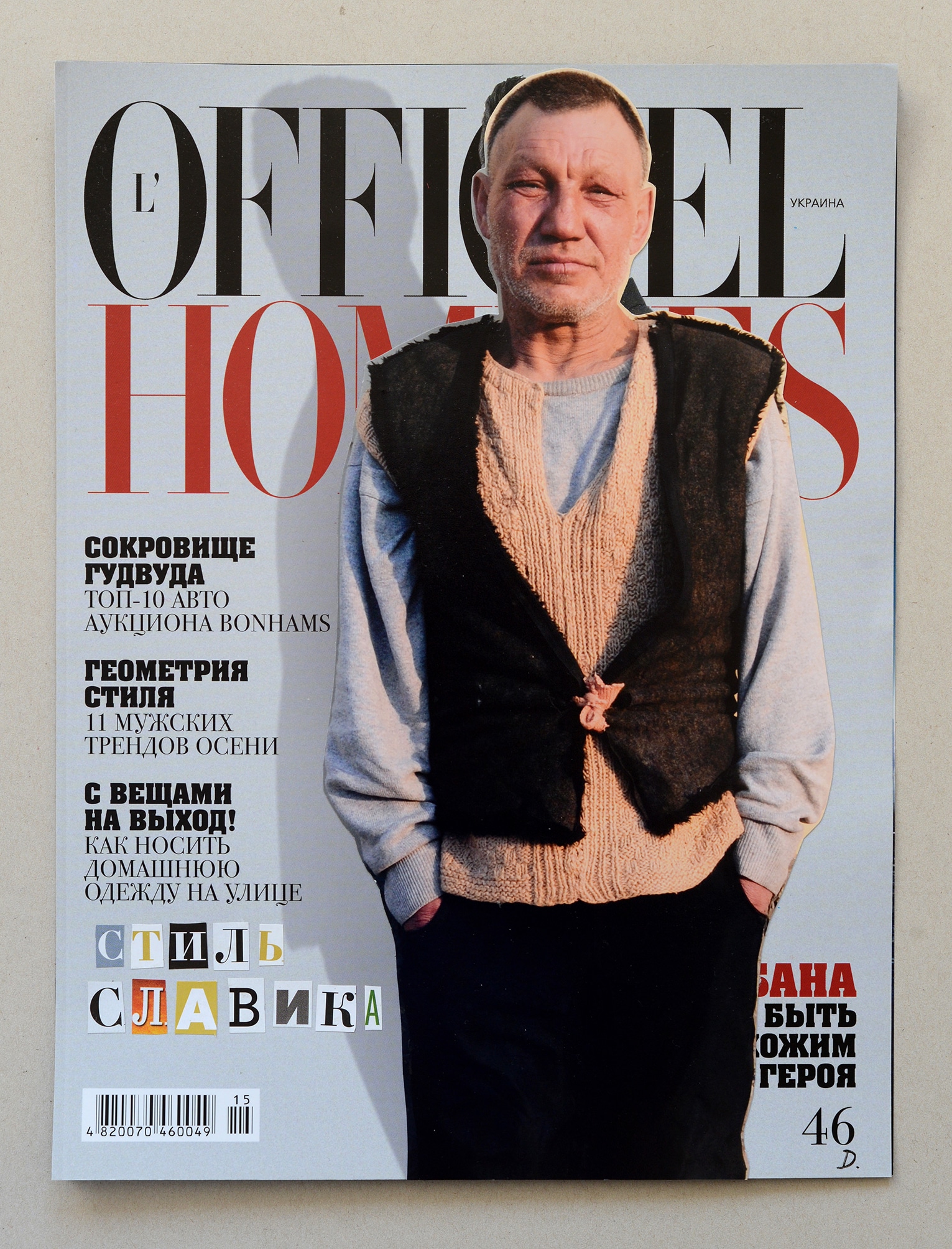

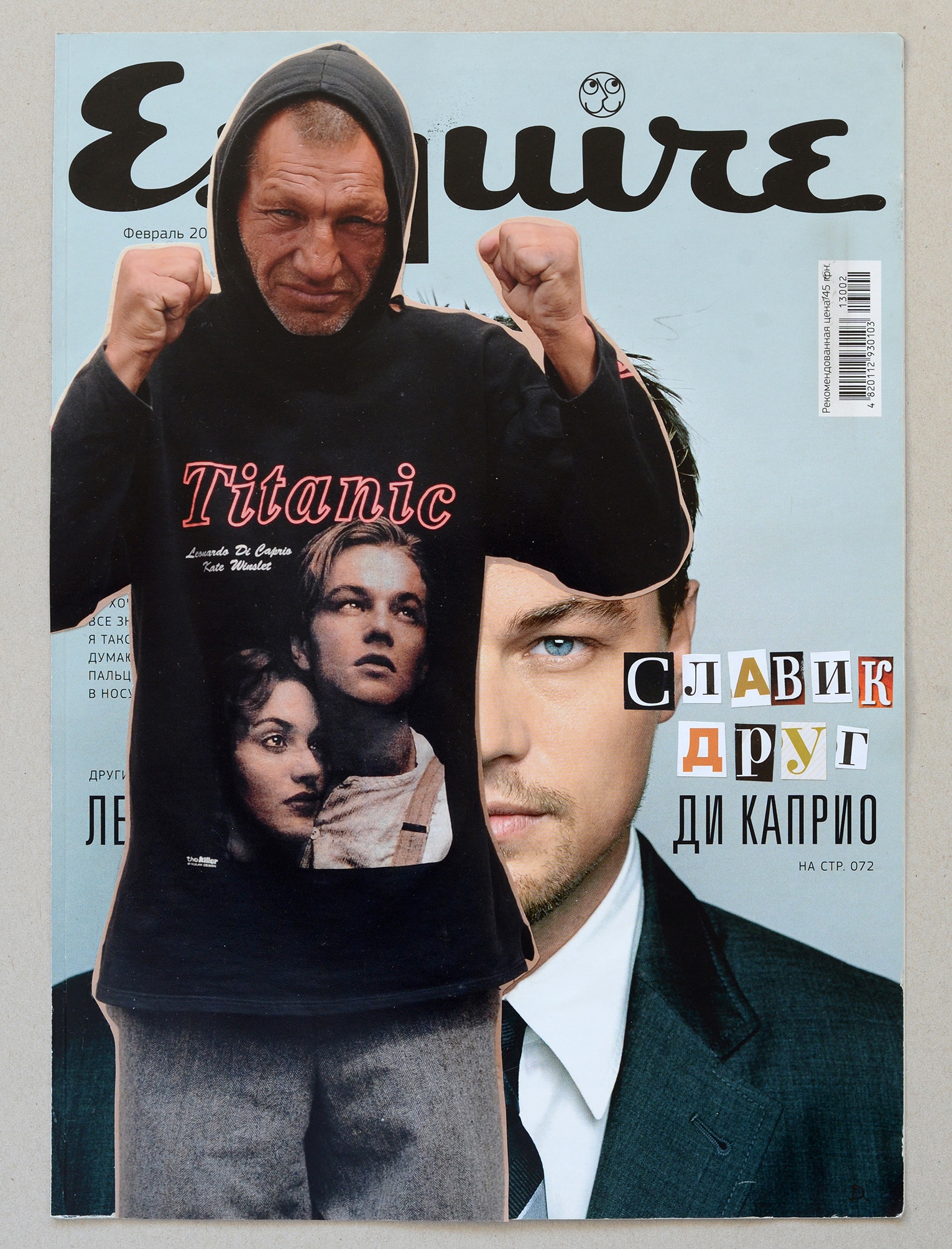

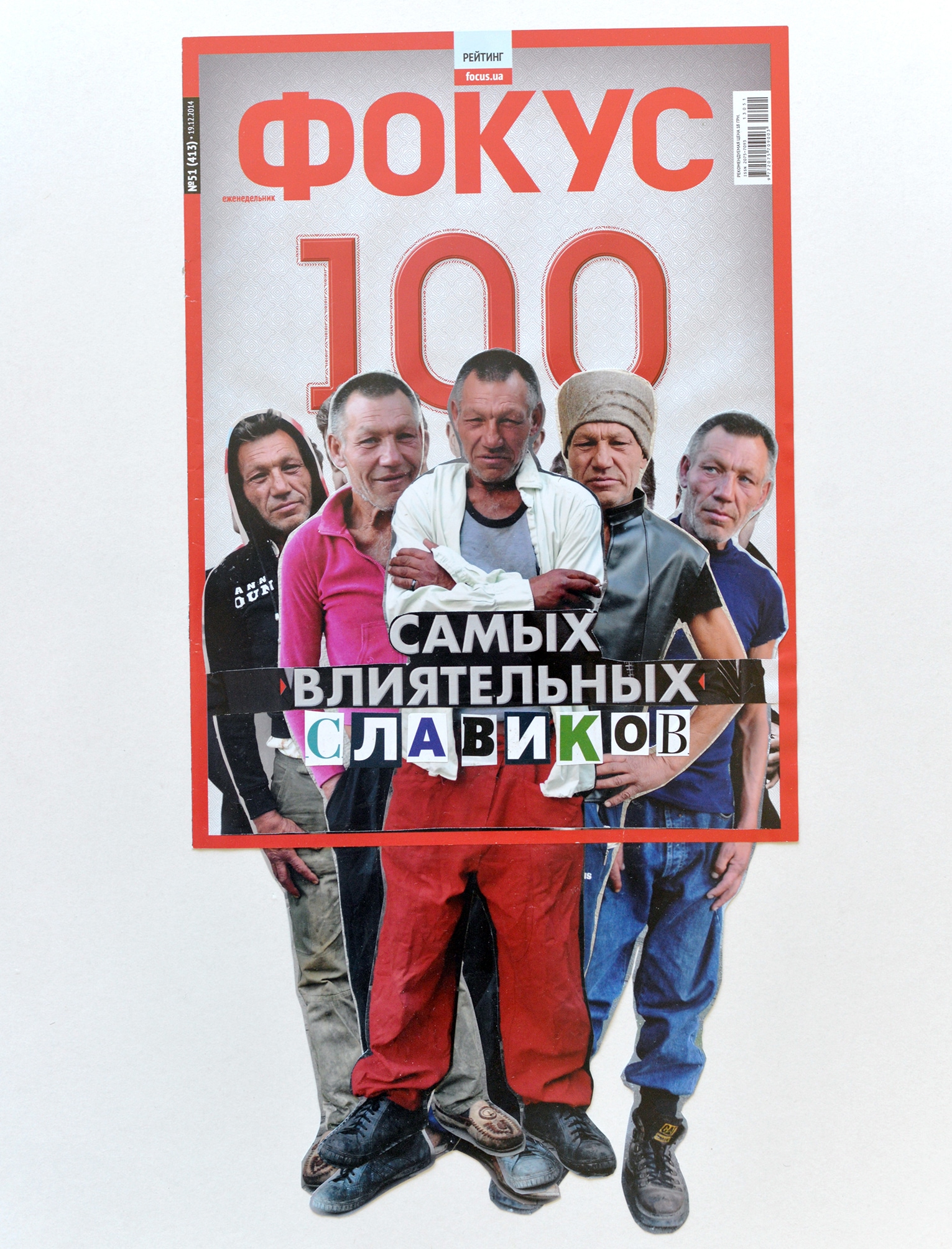

— How did he end up on the covers of glossy magazines?

— Slavik Super Star is the second part of Slavik’s Fashion project. I finished and published the continuation of Slavik’s story before it went viral and the project became widely known. All of the collages are handmade based on the original covers of glossy magazines and Slavik’s portraits. That’s why each of the works is unique and there is only one copy of it.

Life is often this way, although this is very unfortunate, that in order to make it to the cover of a magazine (even if you are a celebrity), you need to find yourself in an unpleasant situation or simply die. And then people would immediately remember all of your merits and achievements or sins and failures, and it’s done: for several days, weeks, or months you are a real star. And it is very symbolic that the Slavik Super Star series came to life after Slavik disappeared.

It is interesting that my creative idea of Slavik Super Star came true: the project about stylish Slavik was published by over 1,000 media outlets all over the world.

— Is it difficult for you to part with a story and start a new project?

— I often go back to old projects, and many stories continue and constantly have new photographs added to them. For instance, I spent ten years taking photographs for the Benches, all while doing other projects.

I always work on several series at the same time, but I ‘deactivate’ most of them, never show them to anyone. My outlook on things changes, and the themes that I used to be interested in stop being exciting for me. As I work on the projects, they may transform or expand, or sometimes ‘freeze’, to be continued after many years. For instance, I renewed a project about horses after a seven-year break.

— You have the series called Putin in Lviv. Do you think a photographer should respond to the political events in the country?

— I shot Putin in Lviv when Russia annexed Crimea and the military action in Donbas started. At the time, I was depressed as an artist, as were many of my colleagues. It seemed that everything has no meaning if your friends are dying in the east of the country.

In Lviv, the images of Putin followed me everywhere: in the news, in conversations, in the chants of football fans, in graffiti, and on the posters where Putin was depicted as Hitler. Putin was made of chocolate, his portrait was on targets at shooting ranges, in the toilets, and of course on toilet paper — this is a conscious reaction to Putin. Wherever I went, I saw the variations of Putin, and the unconscious awareness of this reality grew into deliberate work on the project.

An artist is a parasite by default, because he reacts to relevant issues, voicing his idea. While solving a local problem or trying to save the world, he cannot stand aside, and often reflects the historical period like a mirror. At the same time, we need to differentiate between eternal and politically-conditioned work, because artists will always react to politics. The question is, what they do it for and which work remains for the generations to come.

— Along with working on personal projects, you also work for international media. How difficult is it to combine art and commercial photography, and is it necessary?

— I separate these two kinds of shoots: with work I make a living, and art is there so that I would have something living in me. Whether to combine work and art or not depends on the case and the possibility to do it — but those are definitely two different kinds of shoots. When you work, you need to do a task professionally and not be bothered by particularities. In a similar way, nothing should distract your from a creative process or hinder it.

— You have many awards for photography. Which of them do you value the most?

— The most emotional award is usually the first one that motivates you to move forward. I hope that the most valuable things are ahead, and that it will not be a diploma or a medal, but a good opportunity or financial acknowledgement of my work: not an award, but a reward. I want to sell my work often and at a high price, which would allow me to be relaxed and do art without thinking about the material side of life.

— Do you plan to continue taking photographs of Lviv?

— Yes, I still take pictures of the everyday life of the city, but fewer and fewer each year. I constantly encounter my own visual templates and repetitions. One cannot just do something without meaning, being just another soldier in an army of visual spammers.

Another factor — it simply became boring for me to take pictures in Lviv. The city changed, it turned into candy for tourists. Real life that was so vibrant in the center disappeared forever. The changes that happened to Lviv are good for the city, but my Lviv is already history, although it has barely been 15 years. I jokingly call my pictures from ten years back ‘retrophotographs’, and I catch myself thinking that it is not such a joke after all.

— What are you working on now? On your social media page there are some photographs with the hashtag #TerraGalicia. Is it a part of a future project?

— They say that everybody starts with landscapes (including me) and often end in the same genre. I needed a visual reboot, and TerraGalicia is one of the three landscape series that I started working on. I am hoping to capture all the seasons of 2017 and probably also the spring of 2018. This project is special because I show the photographs while I am still working on it. I hope that TerraGalicia becomes my visual reincarnation, which will end with the ‘phoenix of photography’, and not the retirement from photography and turning to other art forms.

New and best