Master of Absolutely Nothing Max Siedentopf: “My Favourite Projects Are the Ones That I Haven’t Made”

Photographer and filmmaker. Born in Windhoek (the capital of Namibia), studied in Berlin, and lives in Amsterdam. Publishes Ordinary Magazine, works for KesselsKramer communications agency. Had personal and solo exhibitions in China, the US, Great Britain, Germany, Hungary, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Italy.

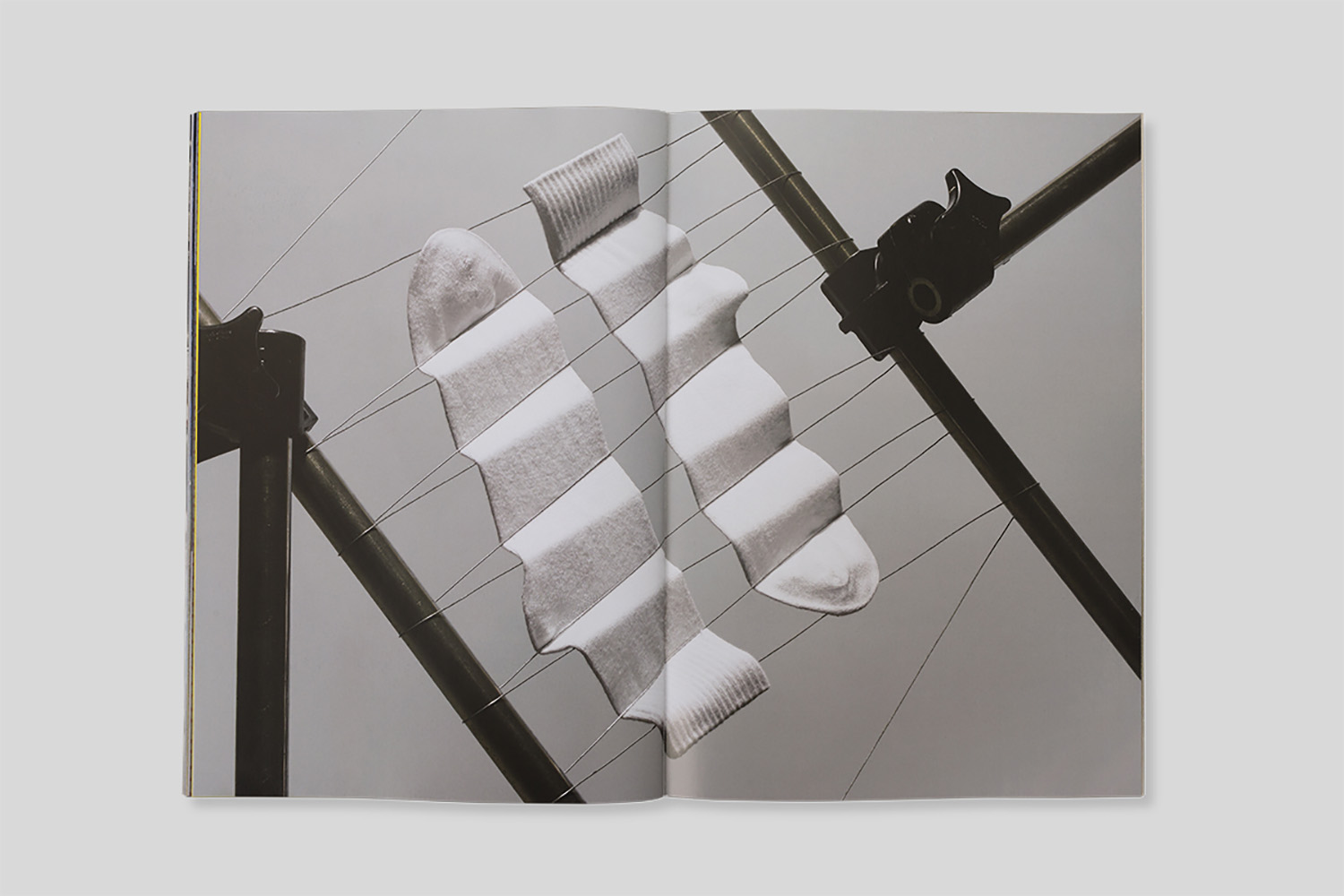

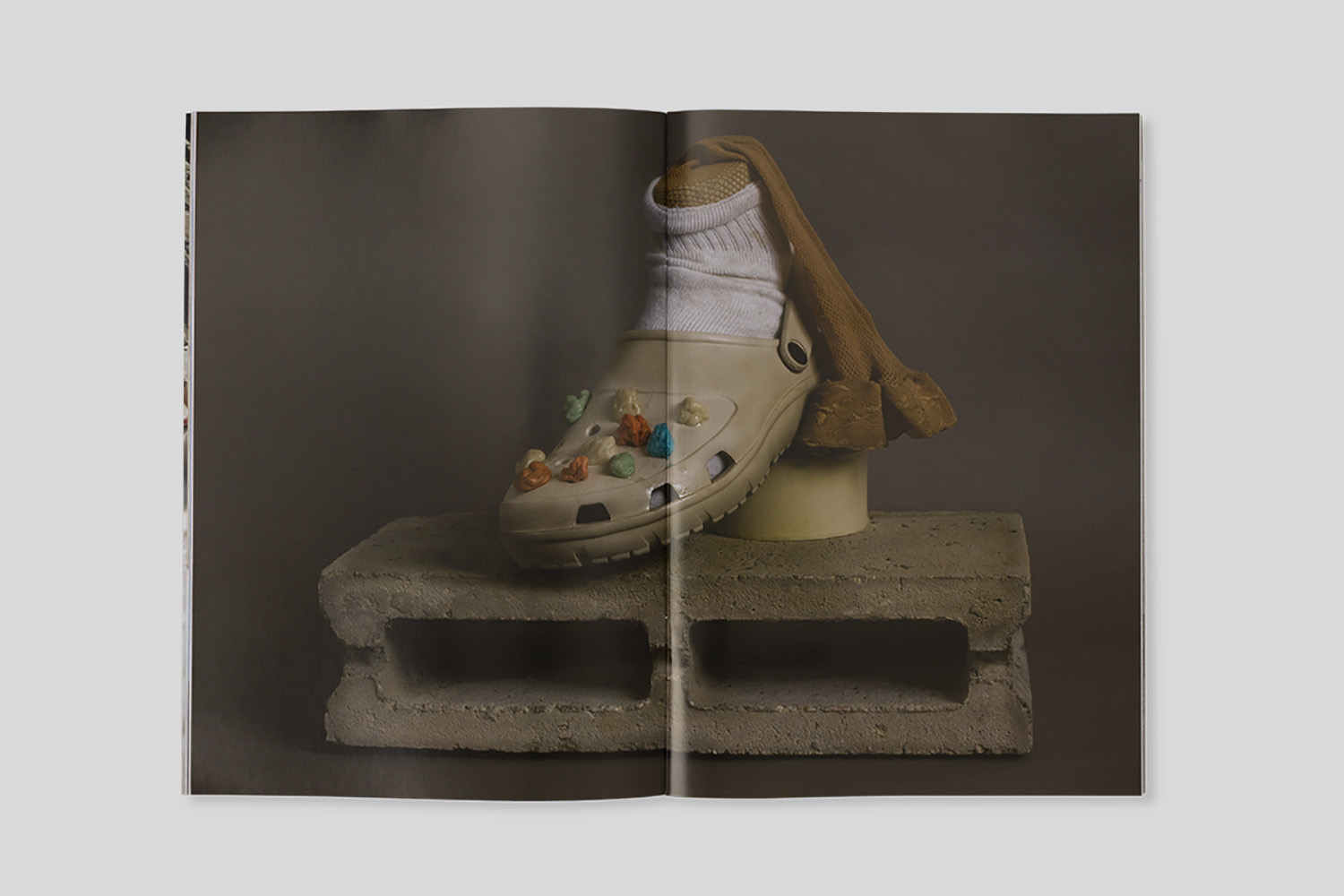

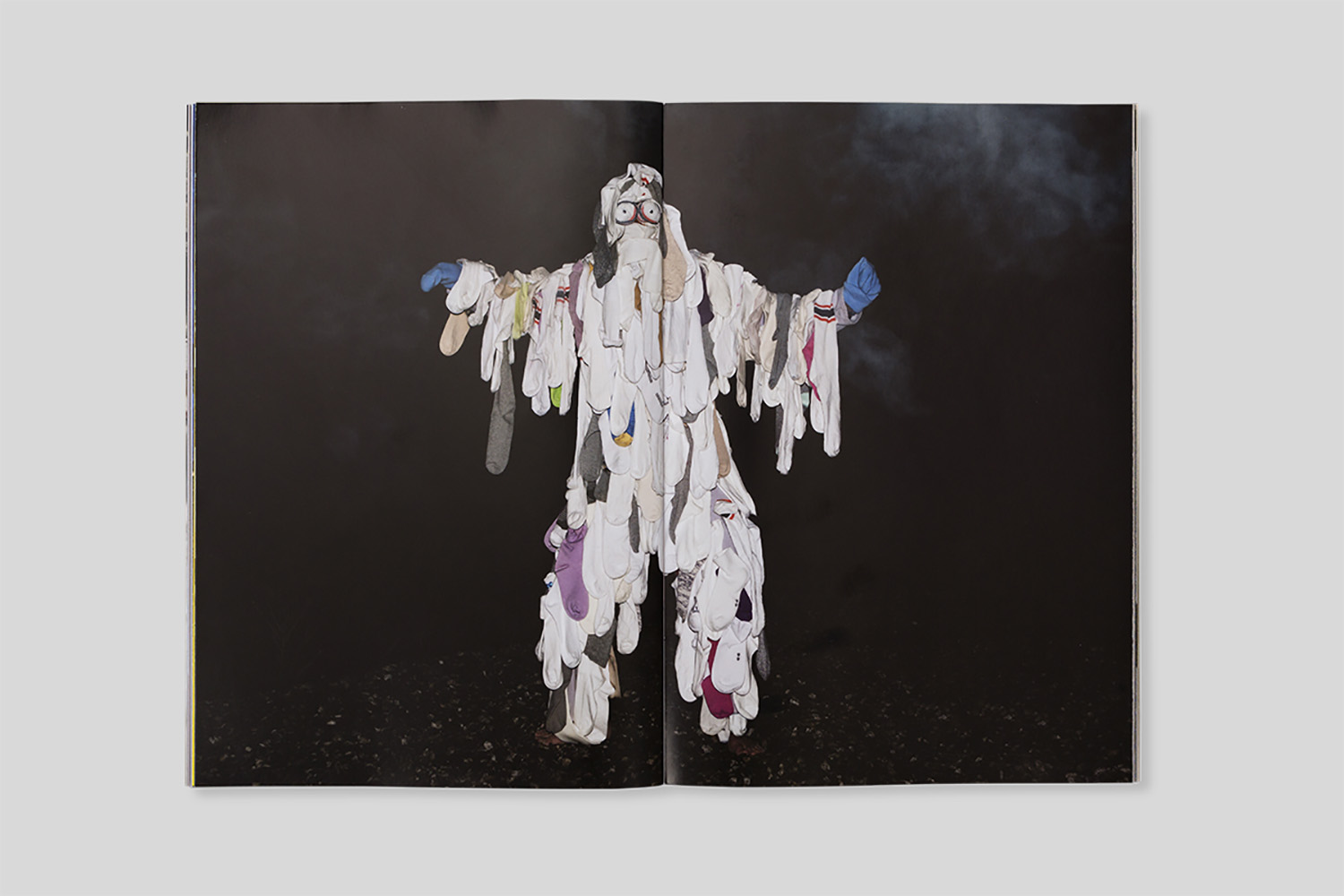

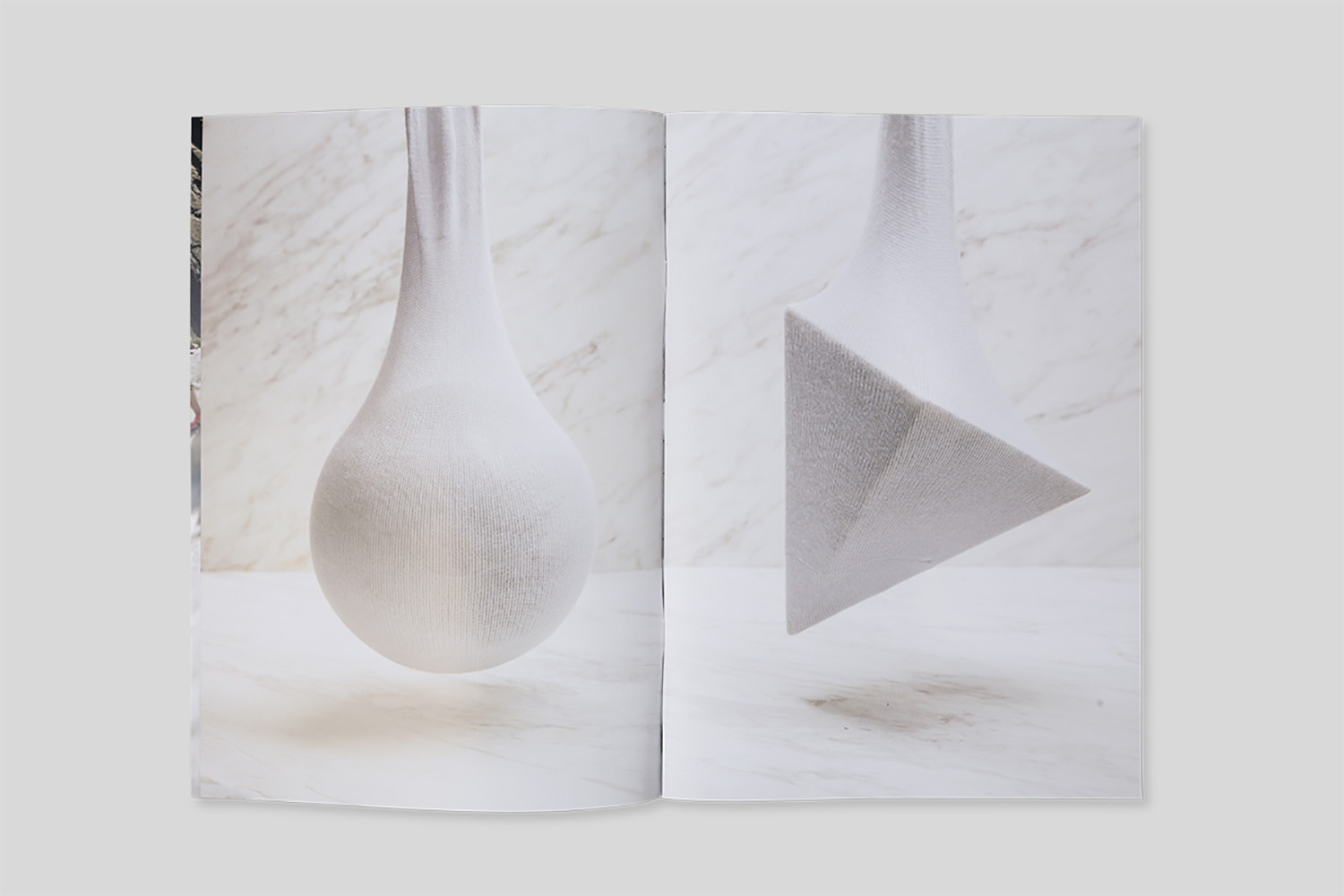

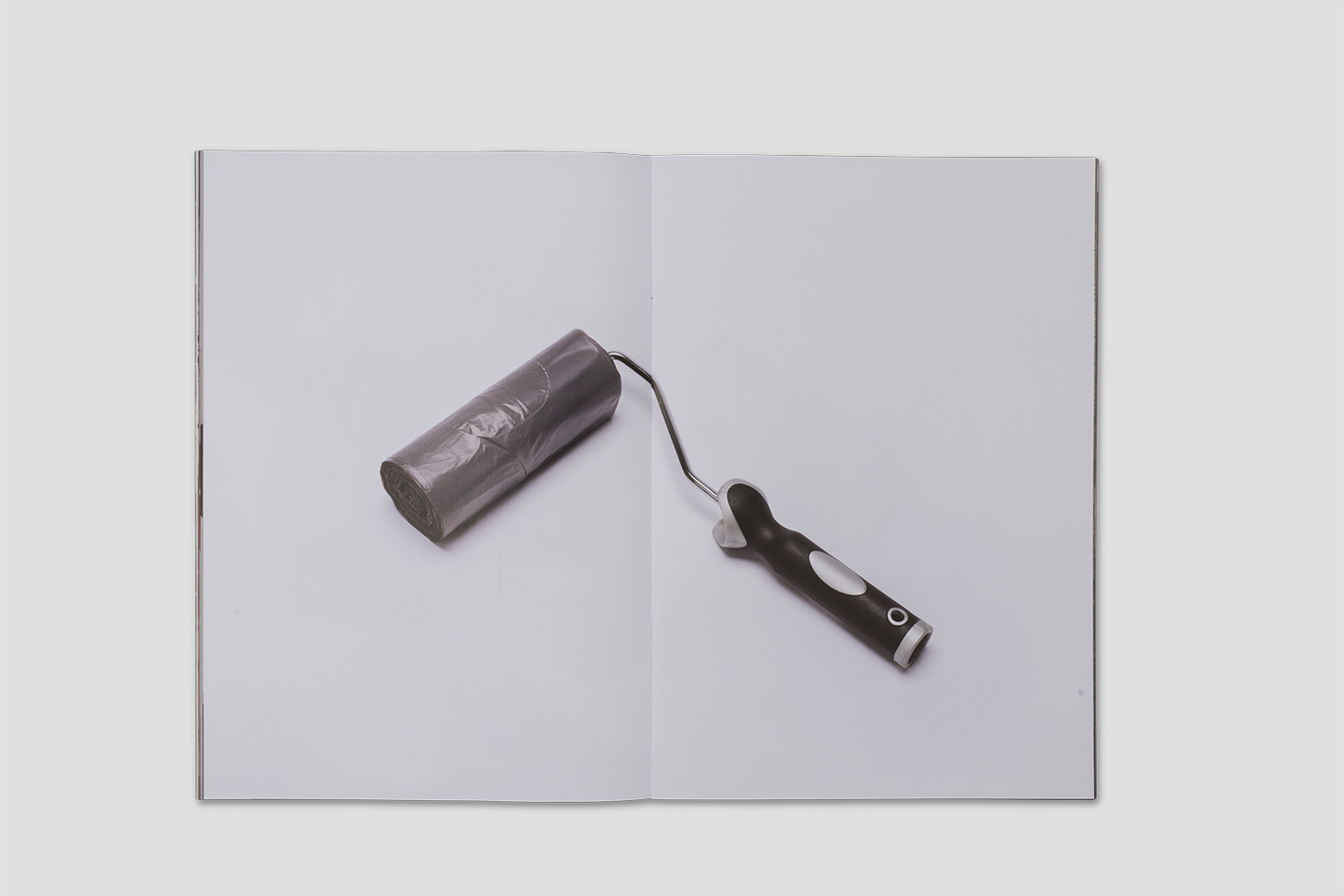

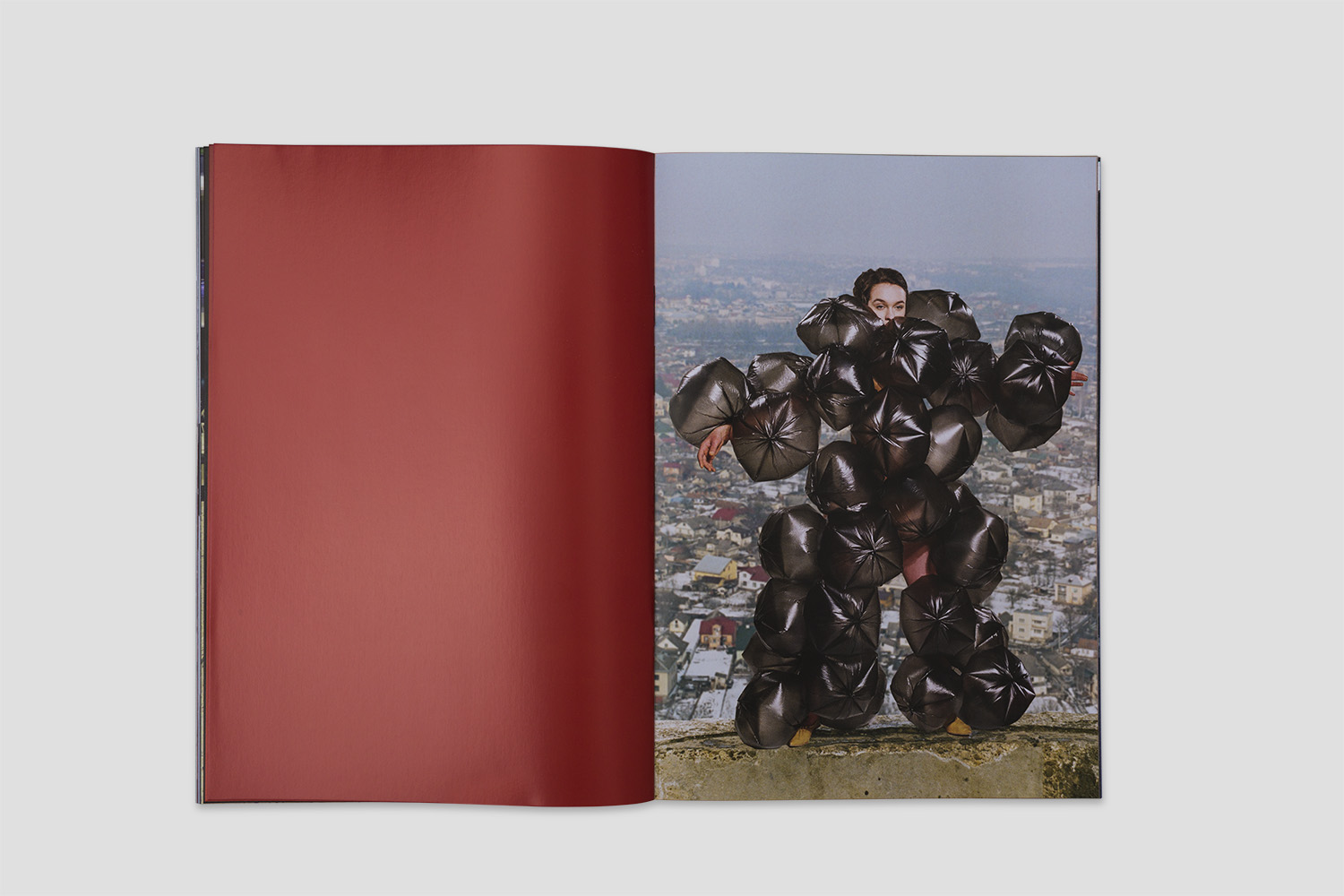

26-year-old Max Siedentopf is extremely productive — he combines personal projects with a daytime job in a communications agency; and he releases a new funny, unconventional, and memorable project almost every month. In addition, Siedentopf publishes Ordinary Magazine — a printed photo magazine where the artists take a new look at usual things. Every issue is dedicated to one everyday object, such as cotton swabs or garbage bags. The artists who took part in the project include Roger Ballen and Synchrodogs.

Writing about your work, journalists usually label you as creative. Is this the right definition for you?

I think the problem is rather that people love to put little labels on things. I think that’s overrated, especially in 2017 when all disciplines overlap more and more with the next ones. ‘Creative’ is of course a nice compliment but I’d rather go with something like ‘jack of all trades, master of absolutely nothing (except eating doner kebabs)’.

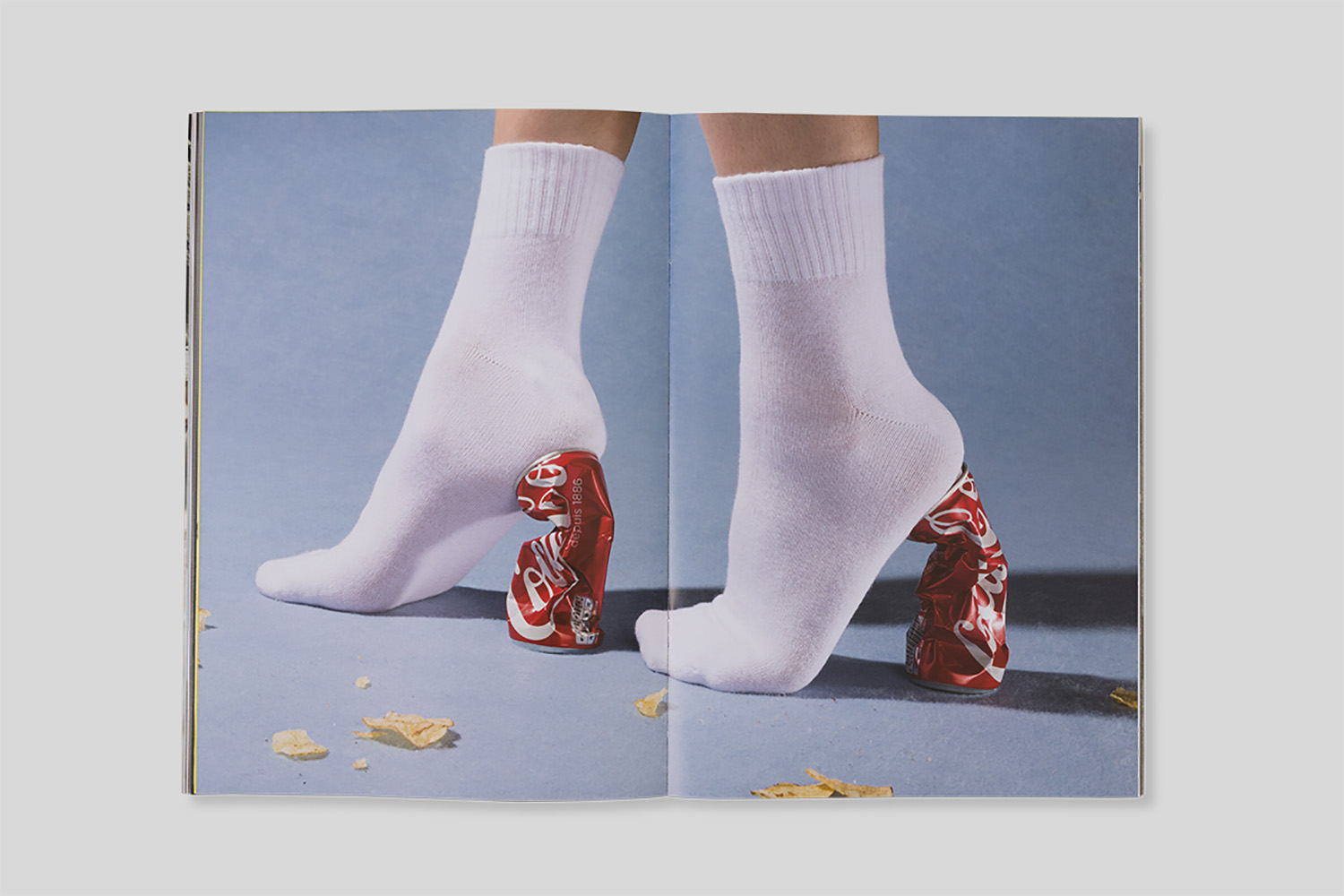

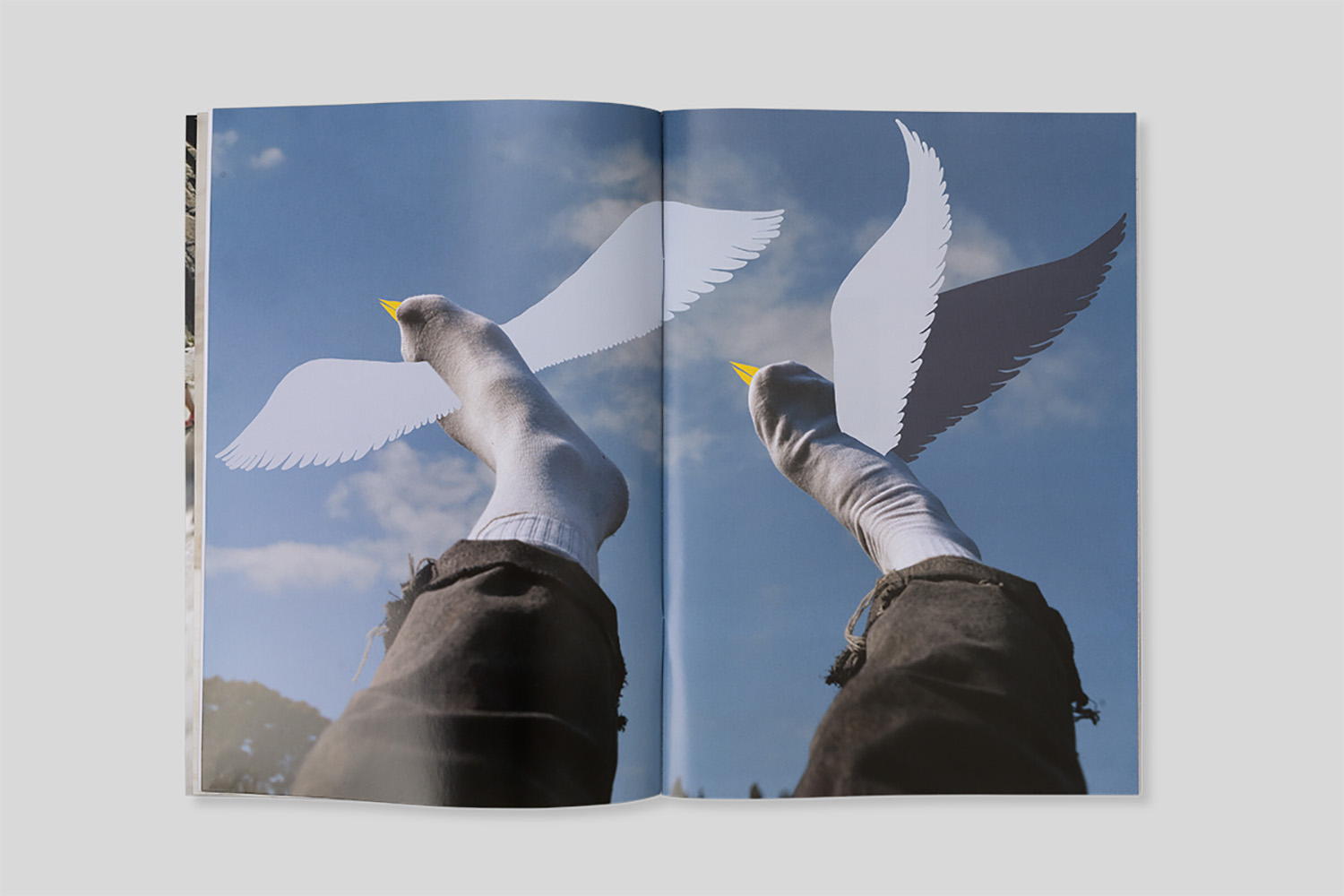

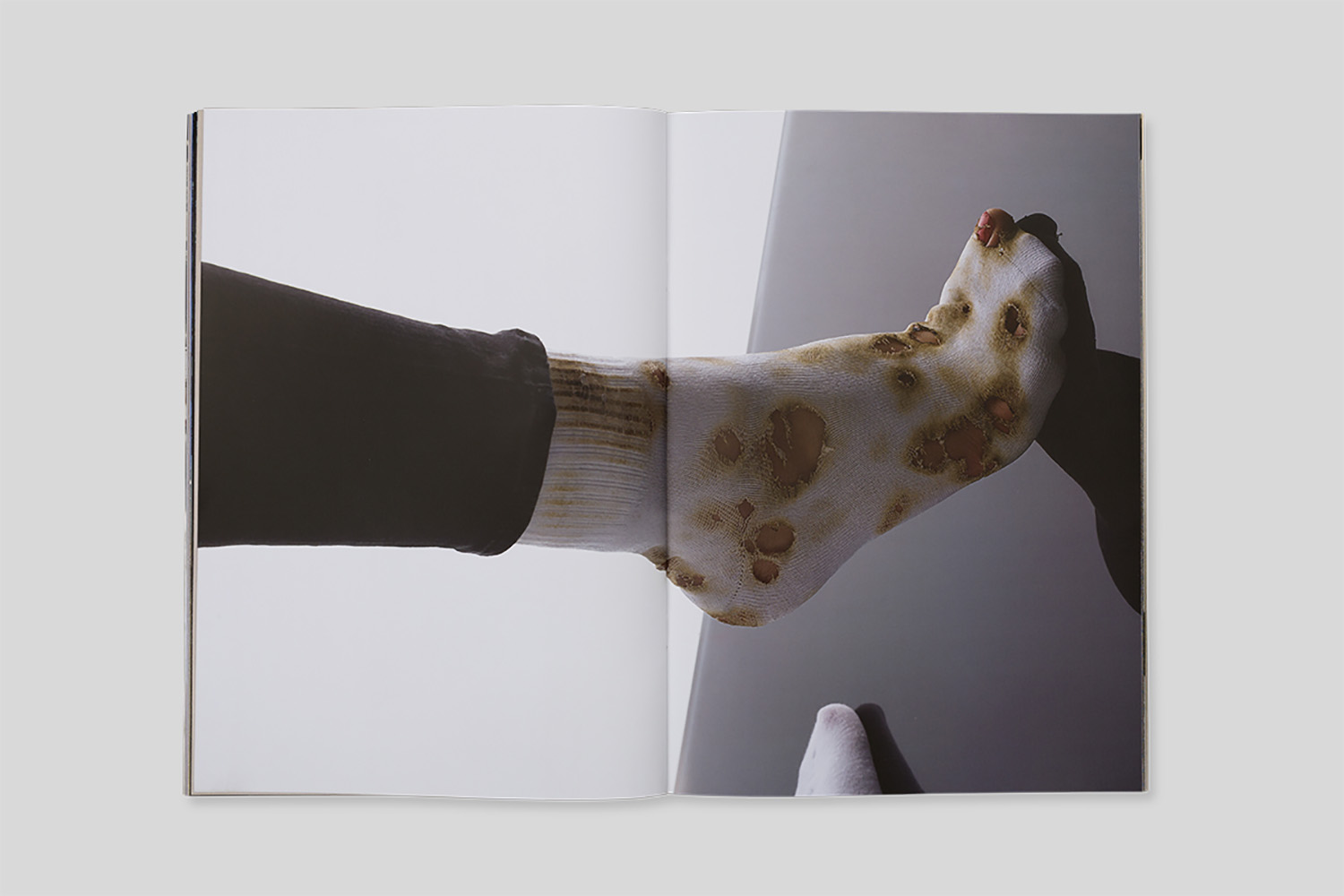

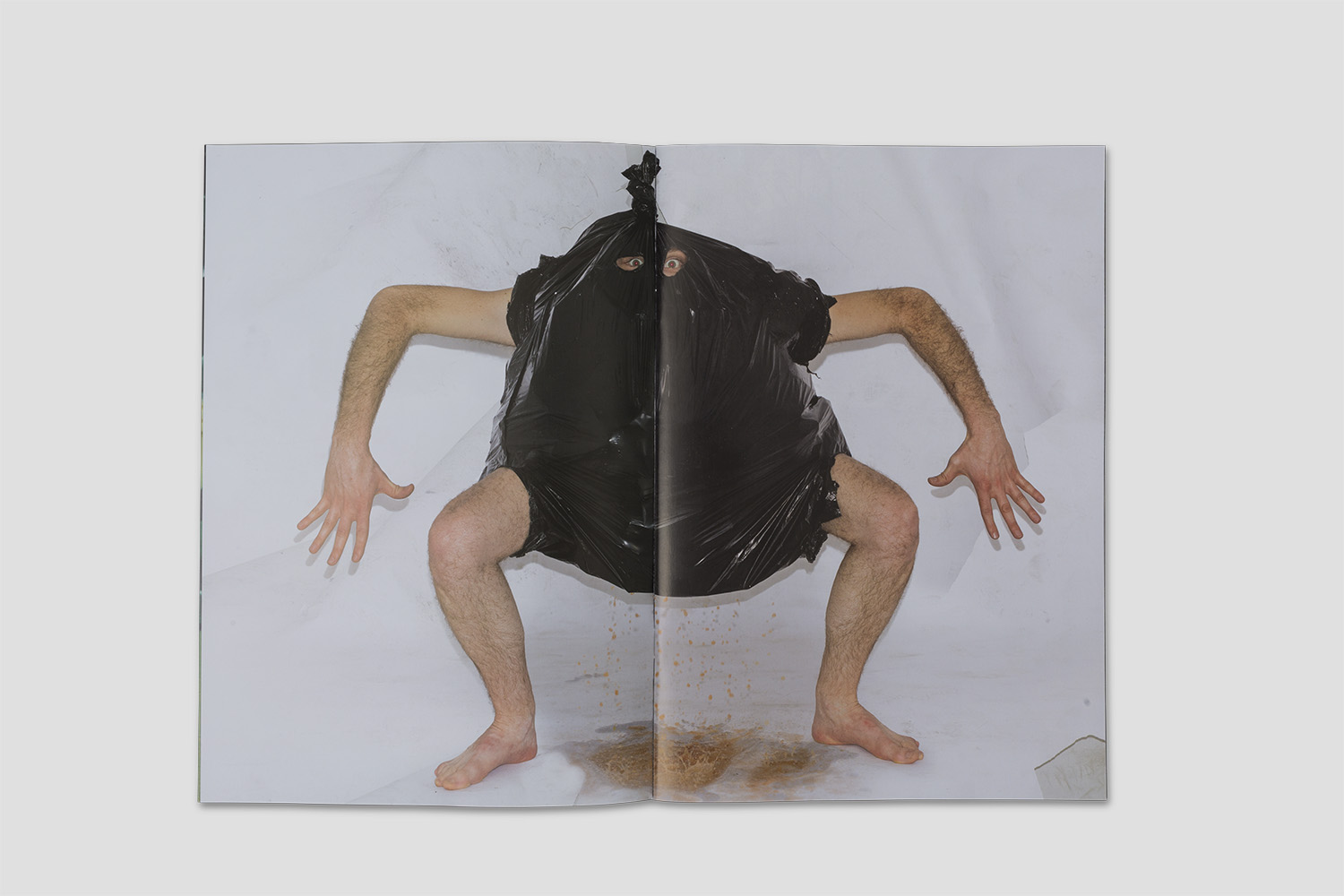

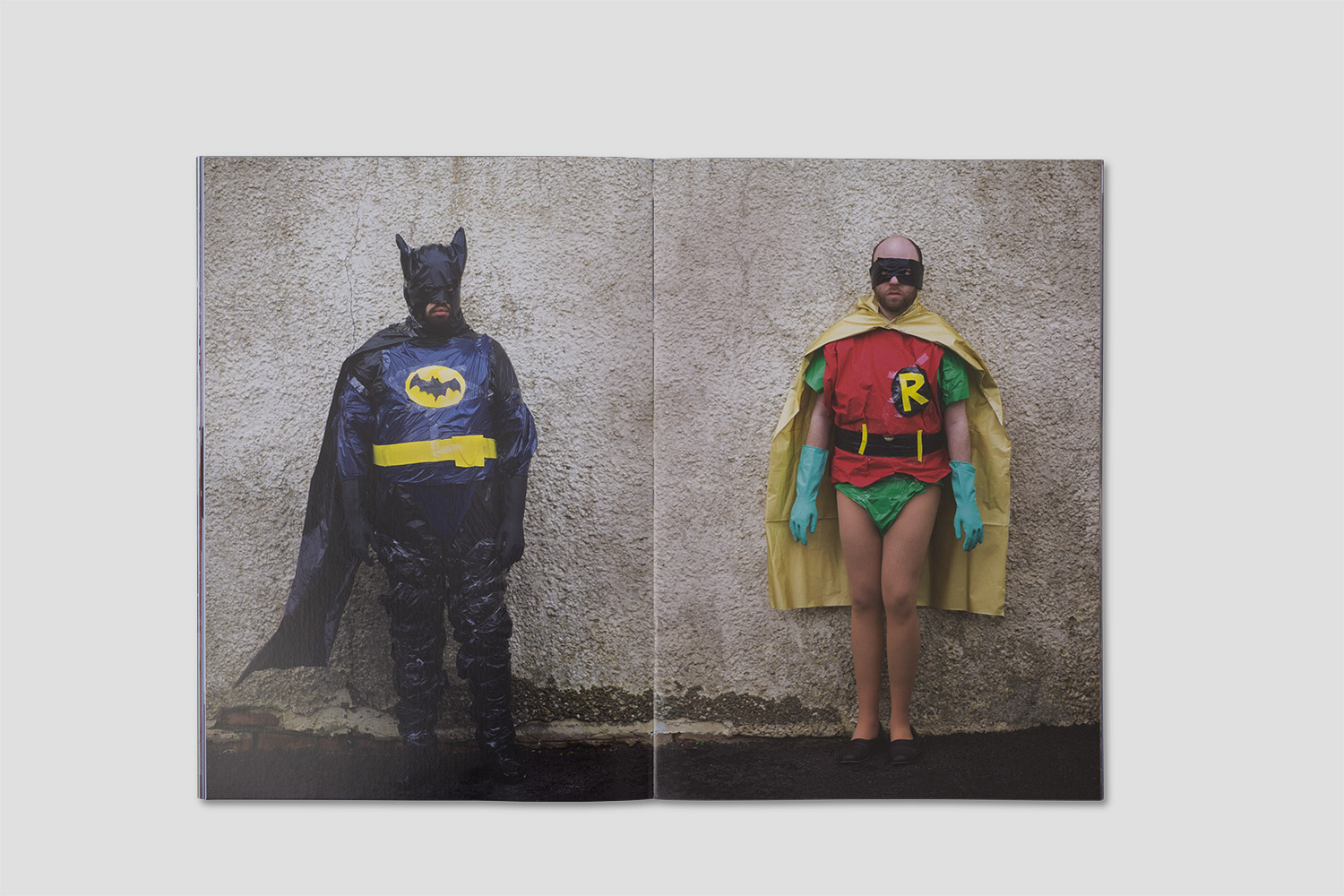

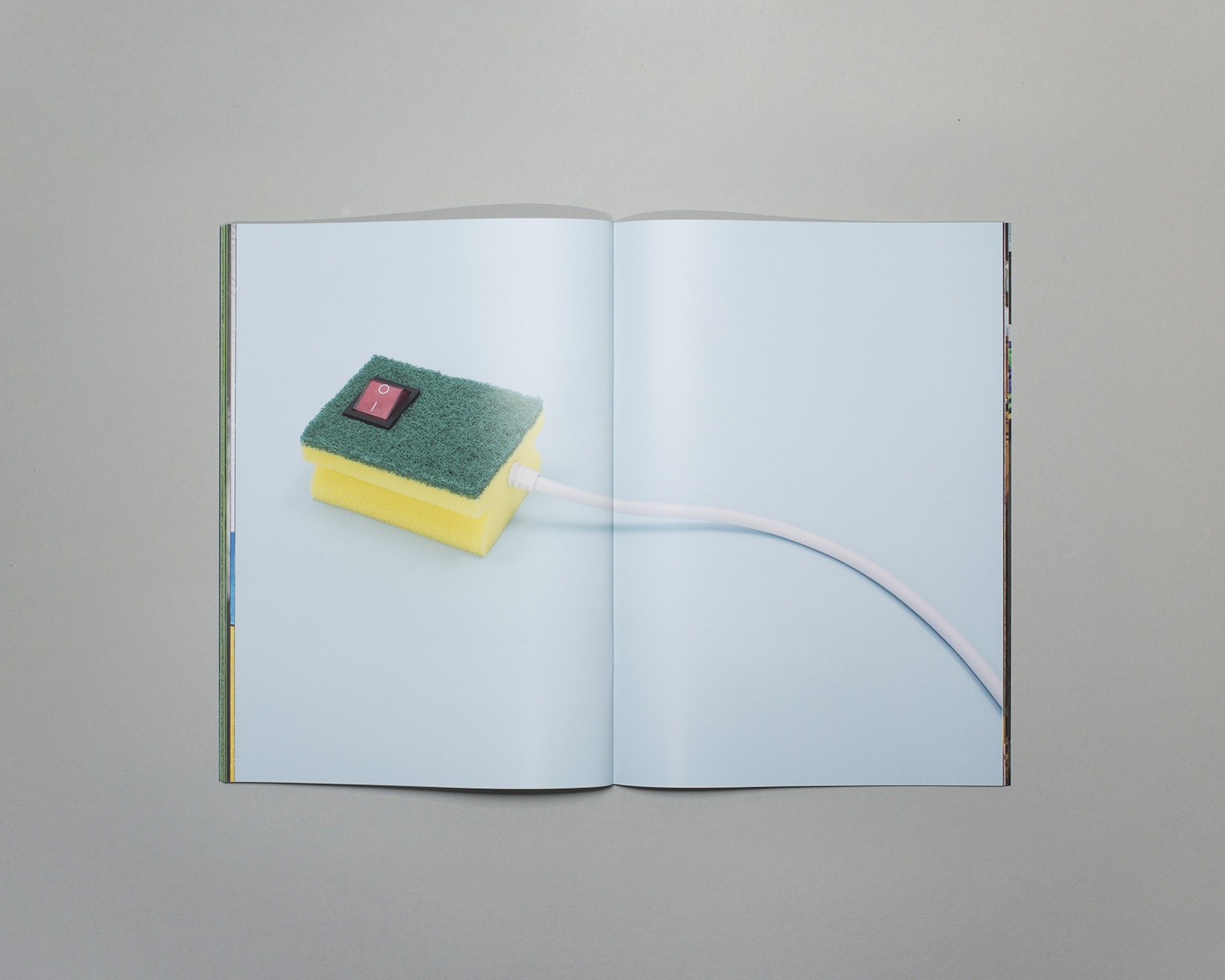

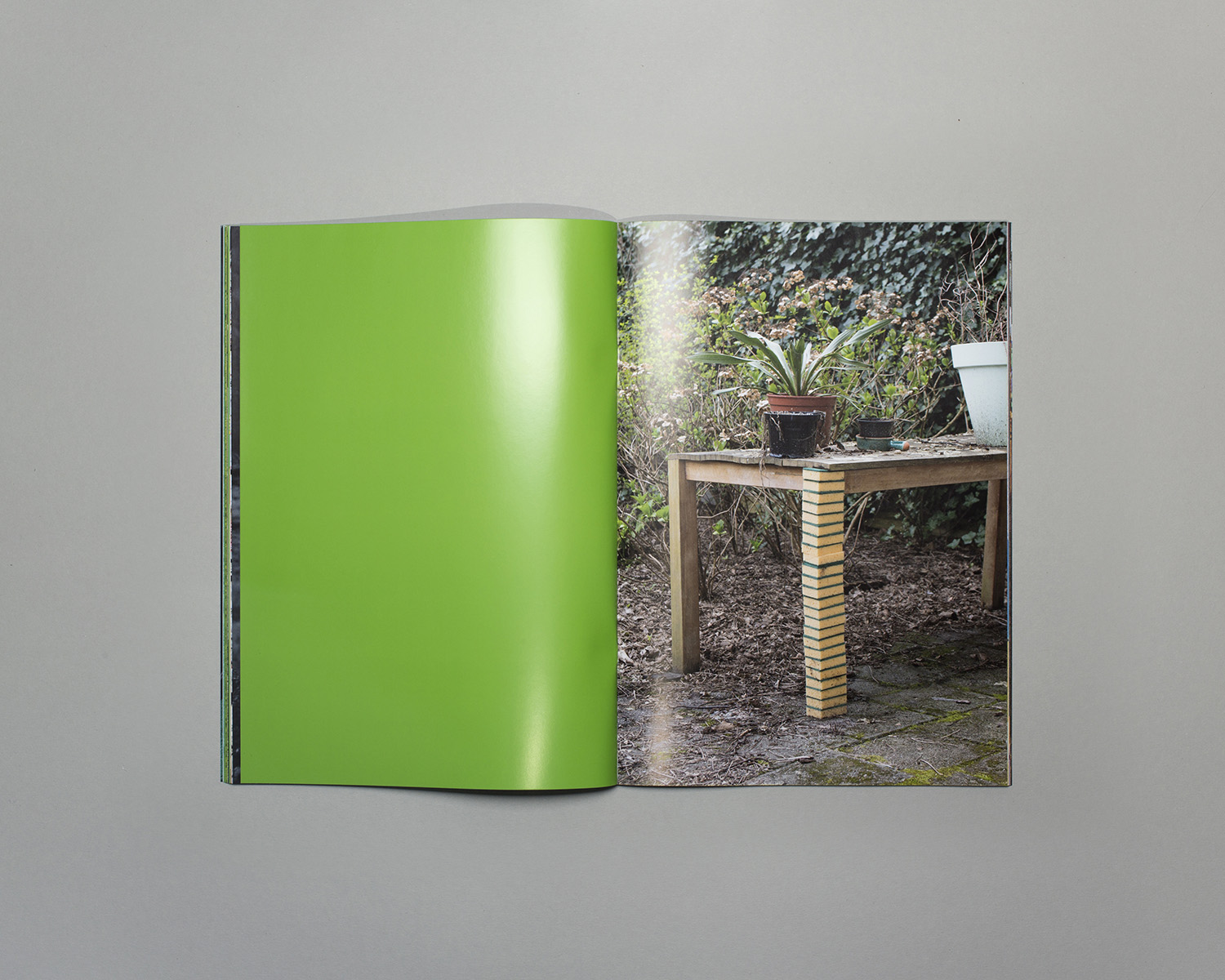

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

From The Worst Hotel in the World series

One of your series was titled Worst Hotel in the World? Why? And what did the management think of this advertising?

I work at the communications agency KesselsKramer and the very first client we ever had was a hostel called Hans Brinker. When the founders of KesselsKramer first went there they realized there was no way you could advertise it as a great hostel. So, instead, they came up with the idea that honesty is the only luxury the hostel has and Hans Brinker became the worst hotel in the world. It was and still is a great success. When everyone tries to be the best, it’s sometimes more interesting to go into exactly the opposite direction. The photo series I made was part of all of this, I tried to find little glimpses of what makes this hostel special. The staff is very proud to work at the worst hotel in the world.

Is it easy for you to both work in advertising and on your personal projects?

I’d say that there’s not a big difference, except that the personal work doesn’t try to sell anything other than an idea and not a product.

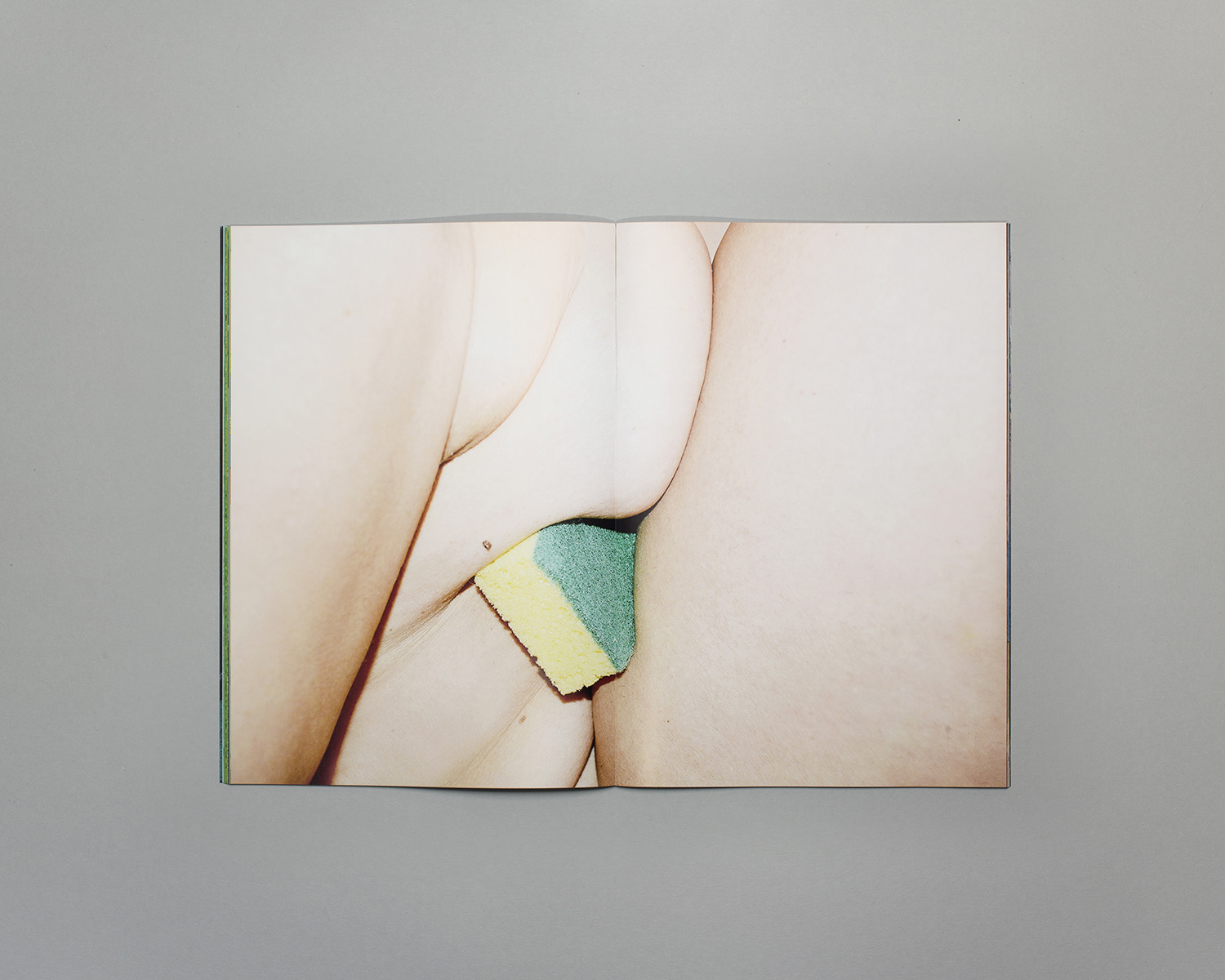

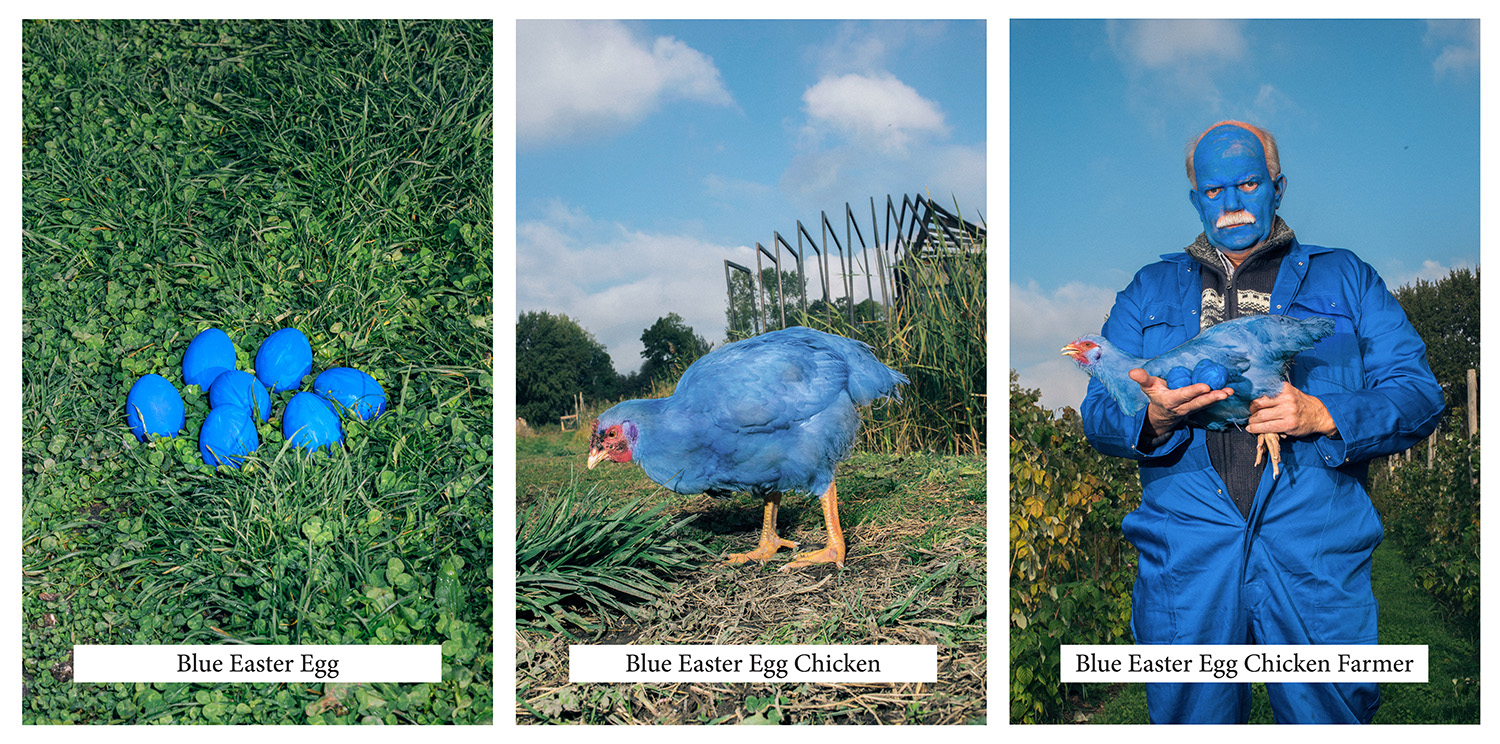

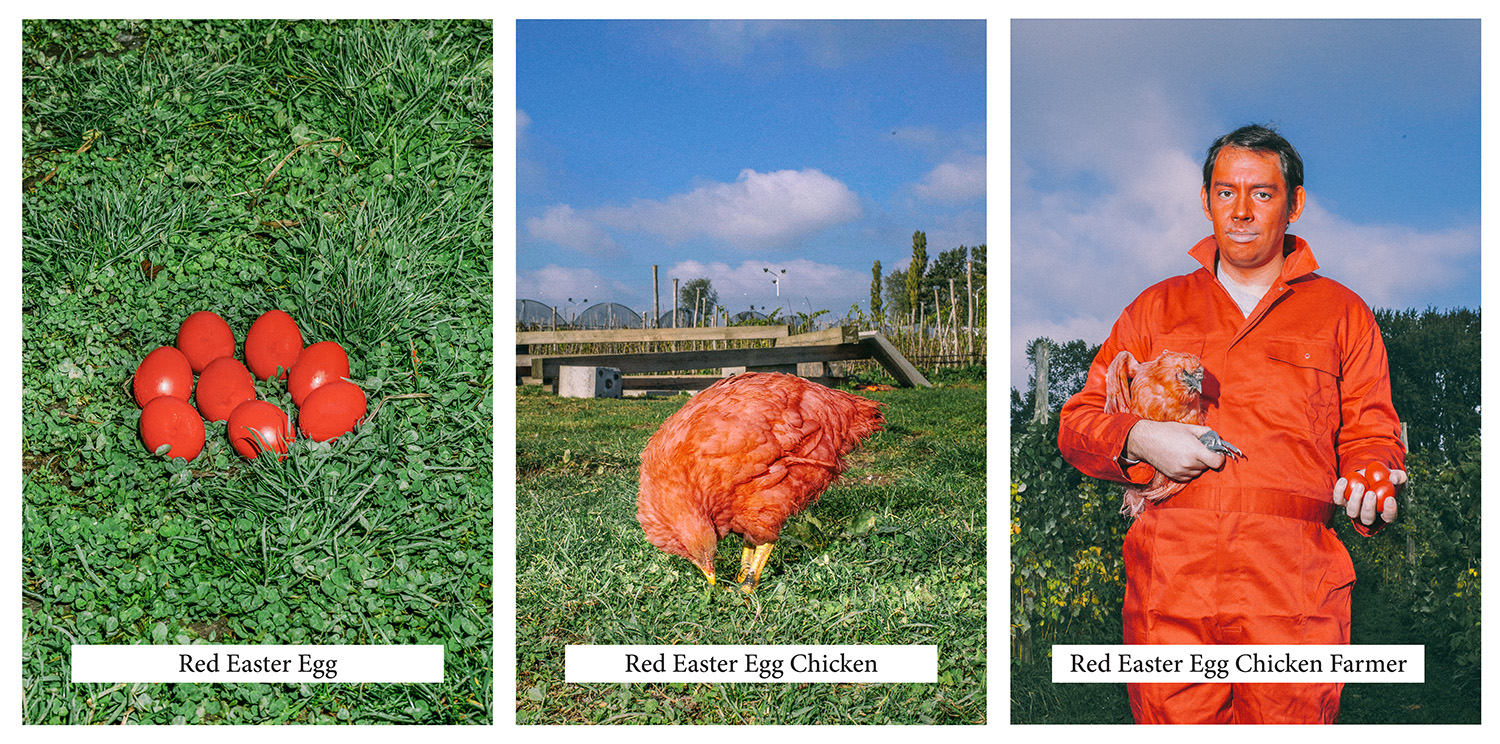

From Eggsistentialism series

From Eggsistentialism series

From Eggsistentialism series

From Eggsistentialism series

How do you develop ideas for your projects? How do you know which idea is worth implementing?

Ideas can pop up anywhere, preferably though on a sunny beach. From there on I usually work quite fast to get it implemented. I never know what’s worth implementing, I just go right into it, even if it might turn out to be a big failure. Overthinking if it’s good or not just limits you too much. Even if it’s a totally shitty idea, it’s more about having fun while doing it, than doing only certain things that you know will be good.

Is the idea or the execution of it more important to you?

I would have to say that the idea comes first, because that’s the part of the process that interests me most. However, I also understand the importance of execution, especially today where most people tend to have the same sources of inspiration and you see more and more people with the same ideas. The execution actually then sets you apart and gives you your signature style.

How did you come up with the idea of Ordinary Magazine? Who is on the team that works on it?

I was standing in the shower, the idea suddenly popped up, a month later there was the first issue. I’m running the magazine together with the very talented designer Yuki Kappes.

You involve different authors for each of the issues. How do you find them and how do you select the pictures?

We look for people that a have a special way of looking at the world, finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. The range is from great contemporary artists like Roger Ballen to strippers to grannies from an old age home. Everyone can look at the world differently. We never leave out images we receive, each image that gets made, gets published.

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

From Fifteen Fantastic Fountains series

Can you choose your favourite project? Why this one?

My favorite projects are the ones that I haven’t made. These tend to be the best ones because they didn’t get compromised by any outside factors.

It looks like your mind is flowing like one of fountains from your recent series. When do you find time for all of your projects?

I wake up early.

What makes you do them in such quantity?

Most likely the continuous awareness of eventual death.

From Horribly Happy Holidays series

From Horribly Happy Holidays series

From Horribly Happy Holidays series

From Horribly Happy Holidays series

You’ve been raised in Namibia, used to live in Berlin and LA. Now you are in Amsterdam. These places have very different visual cultures. How did it affect the aesthetics of your work?

It is hard to answer this question about your own work. Nonetheless, I think that each city taught me a lot of valuable things, which were unique to that very place and style of thinking. Those notions naturally integrated into my work and in response probably affected my visual style.

Irony is all over your works. Do viewers always understand it and is it important to you that they did?

Someone smiling because of you is one of the most gratifying things you can achieve. If people don’t get or like the work, no problem, they can simply turn their back to the work and look at work they like. It’s really easy.

Roadkill Trophies

Roadkill Trophies

Roadkill Trophies

Roadkill Trophies

And what do you laugh at?

There are a few genres that I appreciate, but usually dark post-ironic jokes that are also painfully dry are my favorite. They might be funny or stupid, there’s always a lot of truth about existence in there. Here are some of my favorites: “What do a banana and a helicopter have in common? Neither of them is a police officer” or “A priest, a rabbi, and a Muslim cleric walk into a bar. The cleric who abstains from alcohol due to religious constrictions does not drink, and his friends decide to do the same. They spend the night laughing and having a good time.”

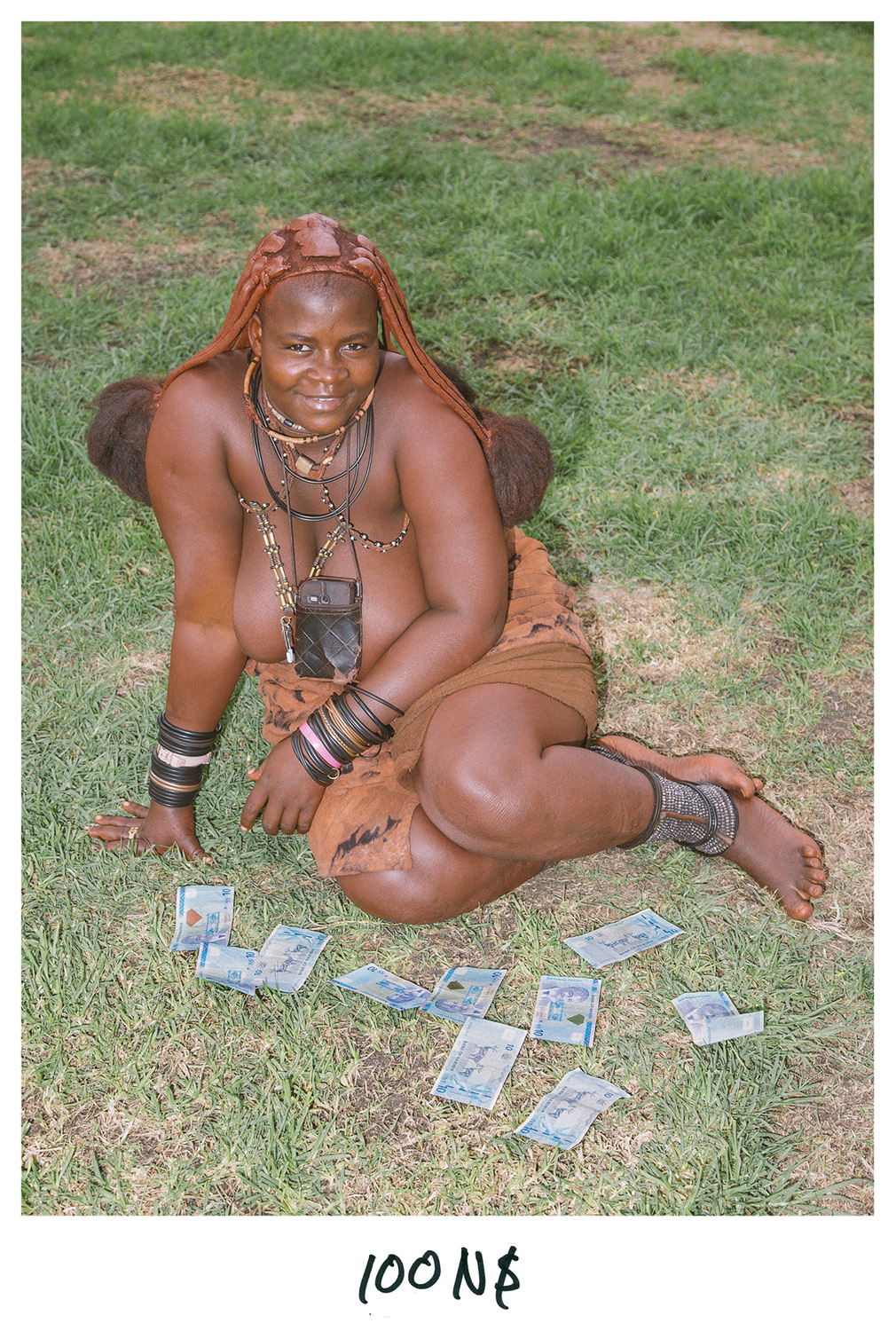

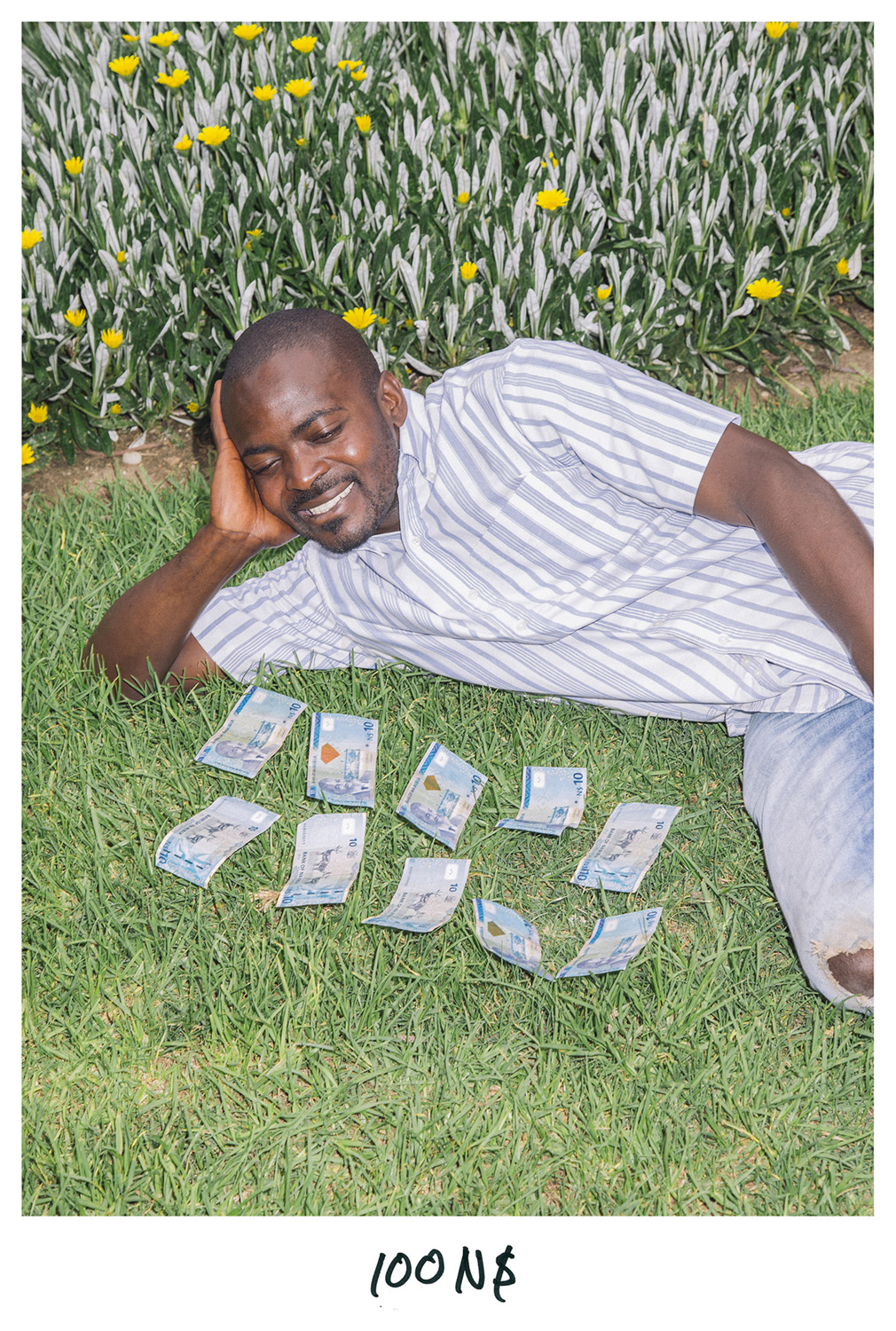

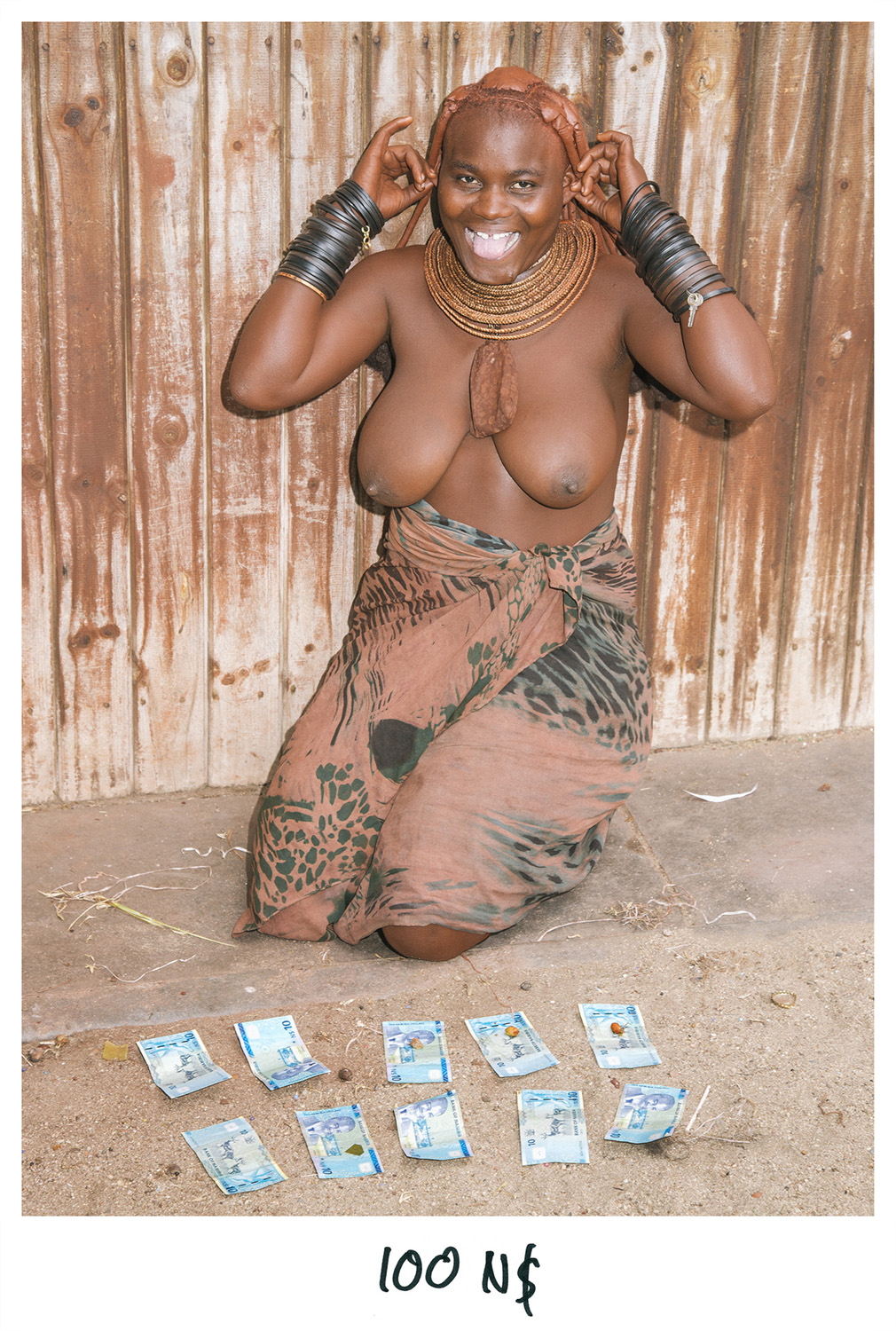

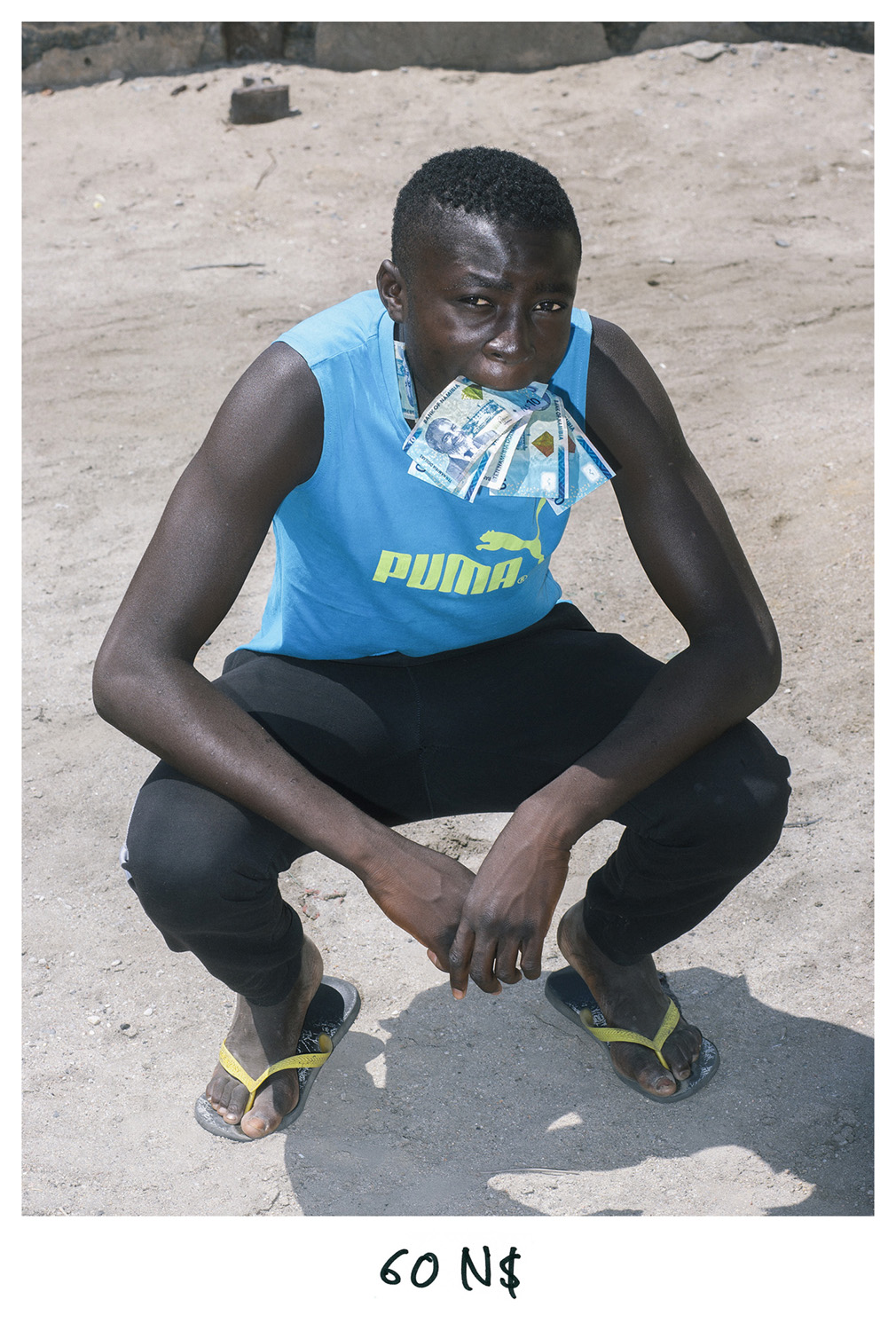

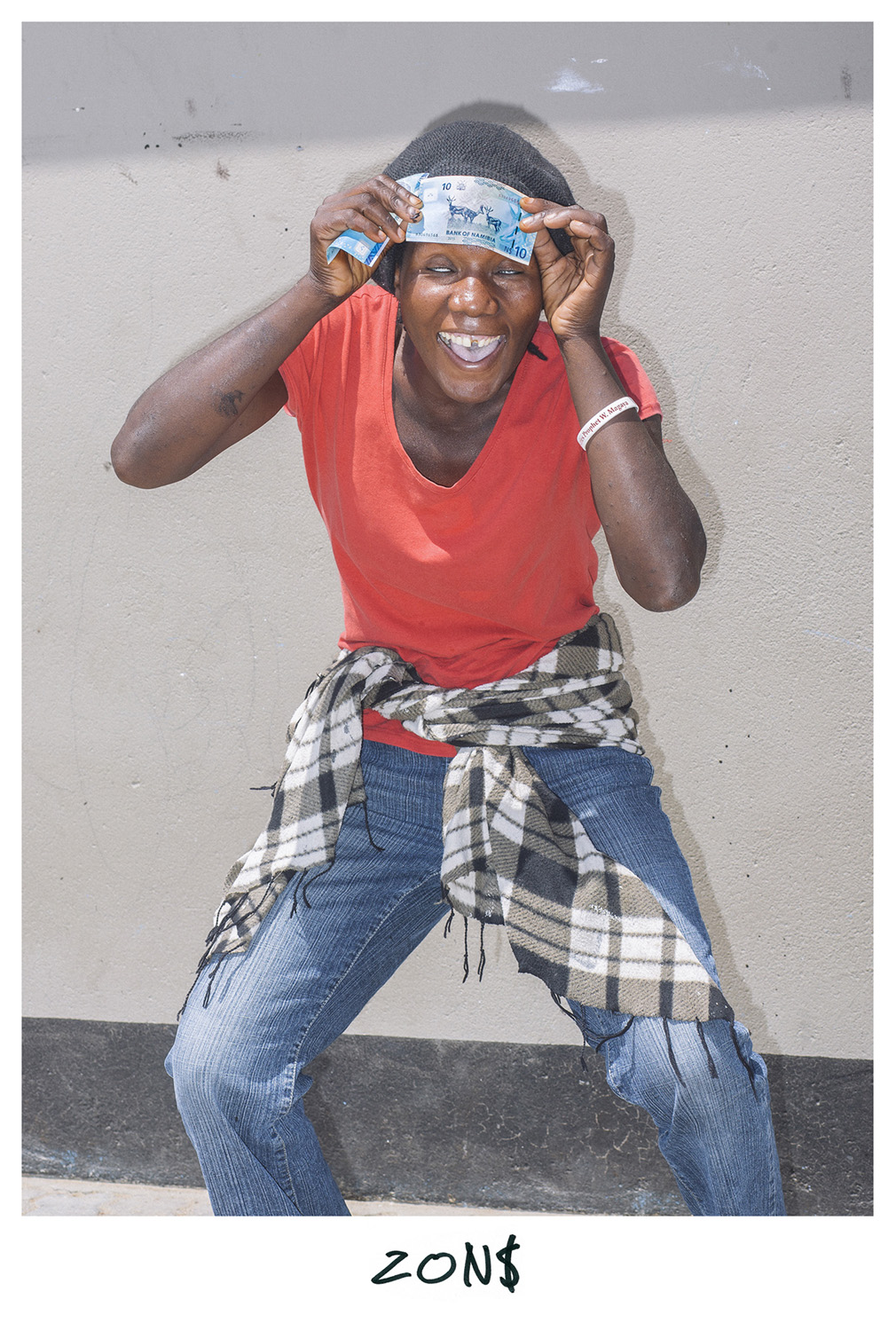

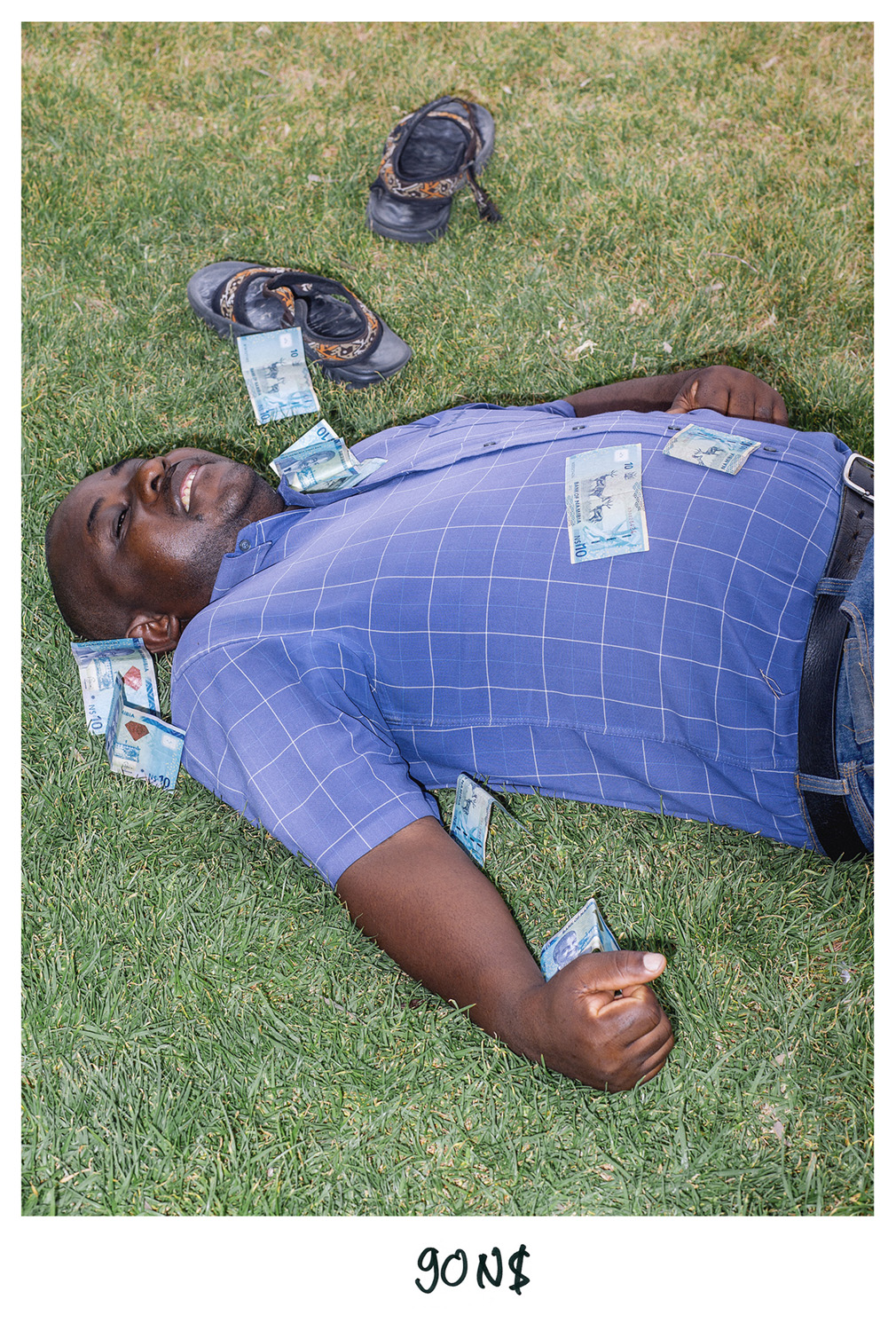

Despite the humor, some of your works talk about serious themes. For instance, in Funny Money you allude to photographers who pay Africans to get them photographed, but fail to ever mention it. In Roadkill Trophies, you speak of the problem of roadkill animals that the drivers just leave on the highways. Do you think it is a duty of a contemporary photographer to comment on such topics and raise them in their work?

I think using your time and creative point of view to talk about serious issues is more relevant than ever and there have probably never been as many topics to talk about as there are today. But I also think that if you don’t want to spend your time doing that, but find greater joy in life by doing something else, that’s ok and you shouldn’t force yourself into something.

Is there something that you would want to do but haven’t tried yet?

There’s still a lot that I want to do and that need to explore new things increases each day. I’d especially love to get into sculpture very soon.

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series

From Funny Money series