Who Am I and Who Killed Me: Portraits of Unidentified Victims

Police can not always successfully identify a person who died. In the US, a DNA test or fingerprints will help only if the person is in the database.

Forensic artists help identify the disfigured remains: professionals analyze the shape of the skull, and after that recreate the face from clay and fiberglass. Such images are often the only chance to identify a deceased person.

Arne Svenson took photographs of unidentified murder victims for several years, to show that behind every clay sculpture there is a human story.

American photographer. Exhibited his work in Julie Saul Gallery and Grey Art Gallery in New York, The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg, Colette Gallery in Paris, The National Museum of Photography in Denmark.

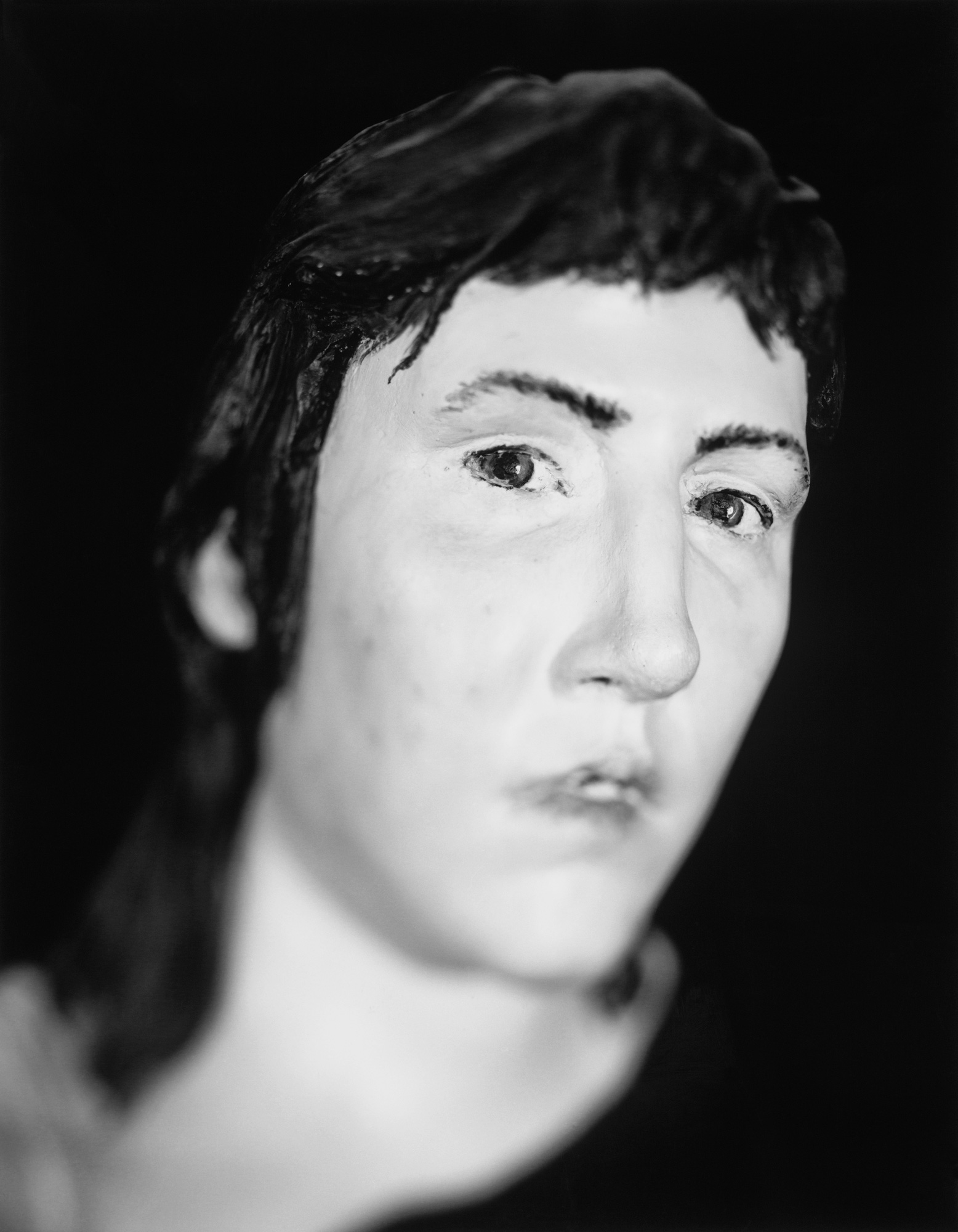

— In 1996, in the Mutter Museum, a Philadelphia-based institution dedicated to medical arts and history, I came across an intriguing object: a sculpture of a woman’s head replete with eyeglasses and a brown, wavy wig. Her mouth was partially open and her heavily lidded eyes were half-closed behind the 1980’s style glasses. She had the look of the utterly lost. I carried the head to the museum director and was told that it was a forensic facial reconstruction sculpture.

I took a sharply focused black and white photograph of the woman’s head, but the life force that seemed to emanate from the sculpture had not translated to it. Frustrated, I put the photo away and more or less forgot about it. A few years later, I met the man who had created the reconstruction, and I decided to again try to bring the sculptures to life via photography.

Linda Keyes. The remains were discovered by a hunter on November 9, 1980 next to a highway in Pennsylvania. The woman was last seen alive a year prior. Linda was identified by her father, who saw the reconstruction in the local newspaper. The cause of death was never determined.

Many artists will create the reconstruction directly on the skull of the deceased, photograph it, and then deconstruct it immediately it in order to return the skull to the rest of the remains.

Looking for work to photograph, I contacted law enforcement agencies, coroners, and medical examiners, the artists themselves, and even the FBI. Many agencies I contacted were very suspicious of my motivations and naturally protective of what are essentially human remains. So it wasn’t until I submitted written proposals and submitted examples of the work that I would be allowed even minimal access to the reconstructions. My argument was always the same – if I could record these reconstructions and disseminate the images then perhaps there was a higher percentage of probability that the victims pictured in the photographs would be identified.

One of the first projects I did was to go to Ciudad Juarez, Mexico and took photographs of the reconstructions of six women whose remains were discovered in a mass grave in 2001 and could not be identified. After the invited forensic artist I knew completed the reconstructions, I traveled to Juarez and photographed the busts.

It was a harrowing experience as every day I was picked up by an armed driver, taken up the back elevators in the Federal Building, locked in a room for 8 hours where I photographed the busts, then taken back out of the building and driven back to where I was staying in El Paso, Texas. In the traffic crossing the border, young women and girls would come to the car and beg — and the faces out the car window were so familiar, so similar to the replicate heads from the mass grave. It was particularly haunting.

Veronica Martinez Hernandez. In 2001, Veronica’s body was found in a mass grave in the suburb of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

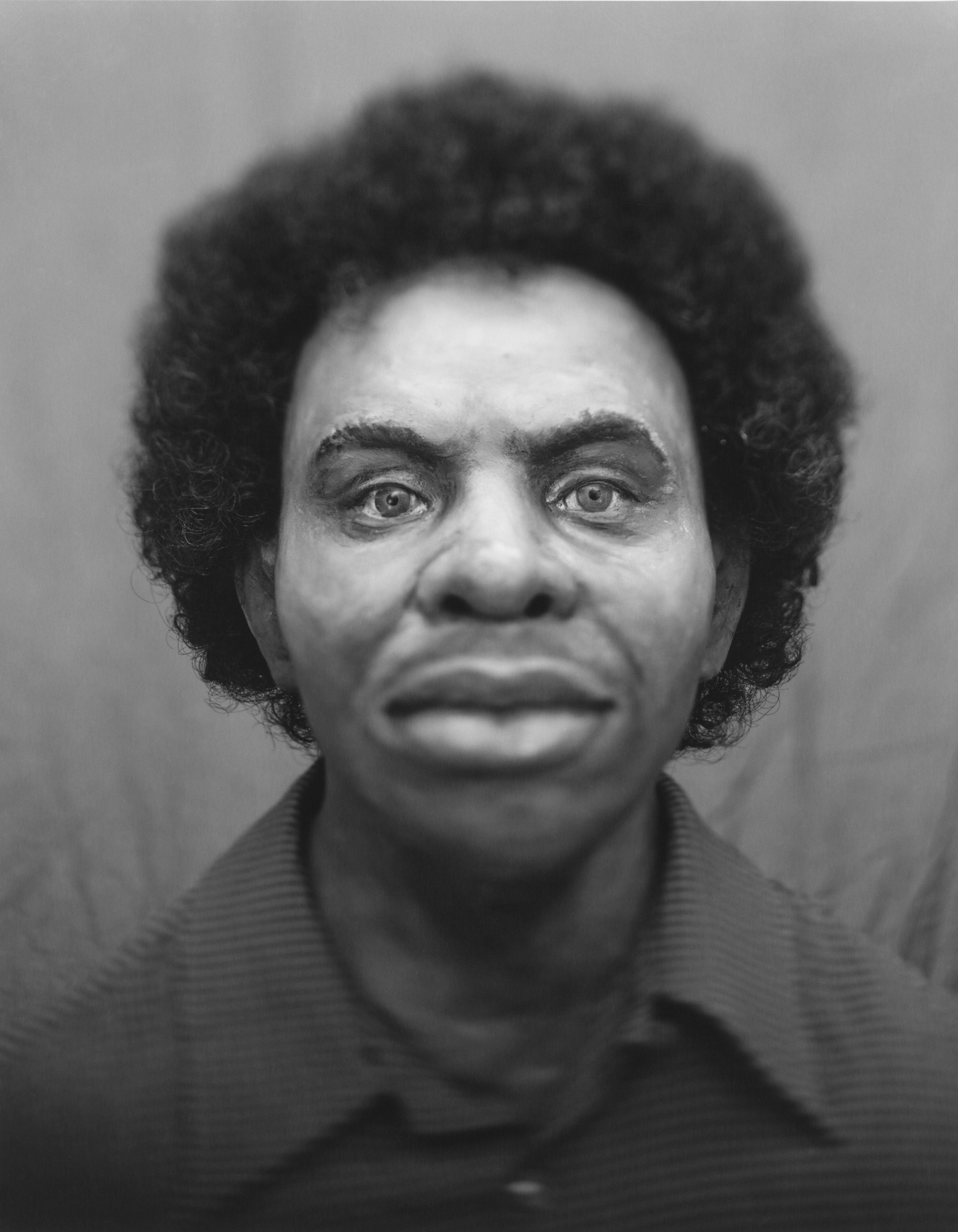

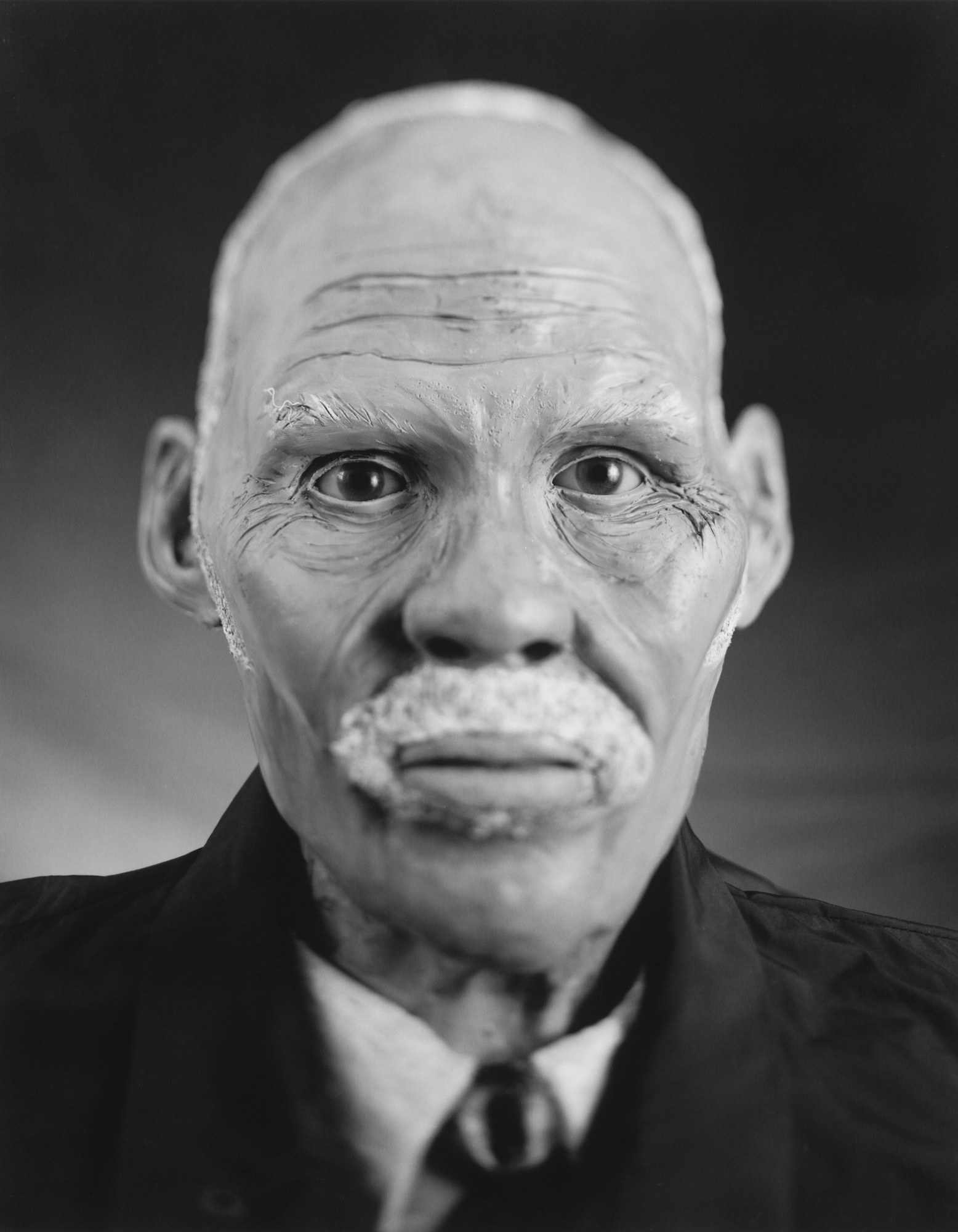

Unidentified man. The remains were found on December 27, 1995, in College Park, Georgia. Investigators believe the bones were at the location for at least a year. DNA analysis indicates that the deceased was an African American male. Identity and cause of death remain unknown.

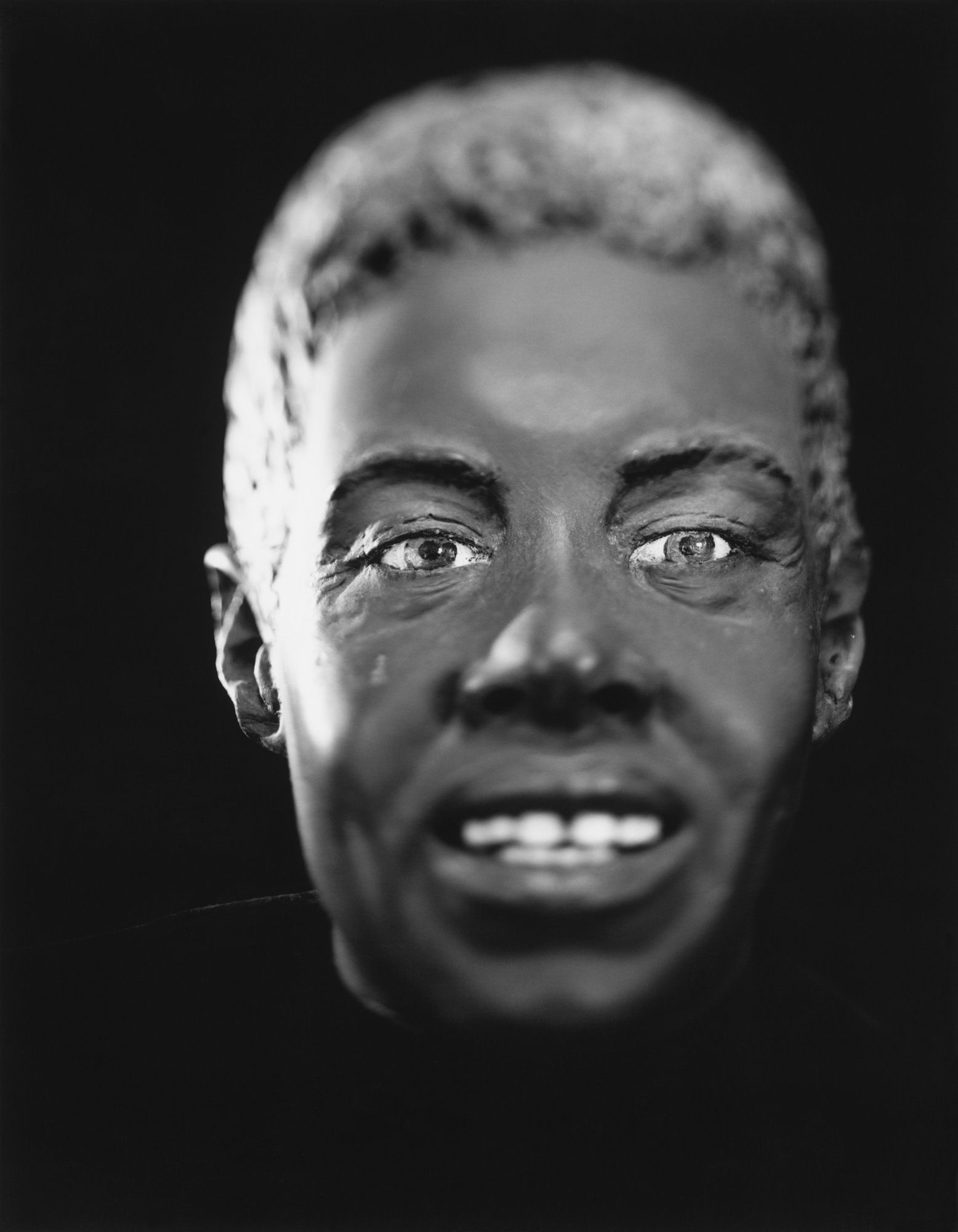

Wanda Jacobs. It is known that she was shot and her body burned in 1986 in Philadelphia. She was identified thanks to the detective who showed the reconstruction to people in neighborhood bars. The case remains unsolved.

I came to understand that it was essential for the eyes of the subject to be focused at the viewer and that the rest of the face must fall out of focus. Most of the reconstruction sculptures stop at the neck; in order to encourage the viewer to see the reconstruction as humanly viable, I had to create the sense that a whole body was conceivably beneath the frame of the image. In order to achieve this, I created shoulders out of anything available at the time (blocks of wood, medical supplies, a coat hanger) and put a shirt, sometimes my own, on the newly created bust prior to photographing it.

Taking photographs in the medical examiners facilities was the most difficult – gurneys carrying the dead would be pushed past where I was working and doctors, their scrubs covered in blood, would come in to visit and see what I was doing. I could never escape the fact that the sculpted head in front of me was the representation of a human who had died a hard death and, to compound the misery, had no name, no identity.

I hope that I’ve brought a sense of dignity to these lost souls. As they stare at the camera two questions must be asked for them “who killed me?” and “who am I?”

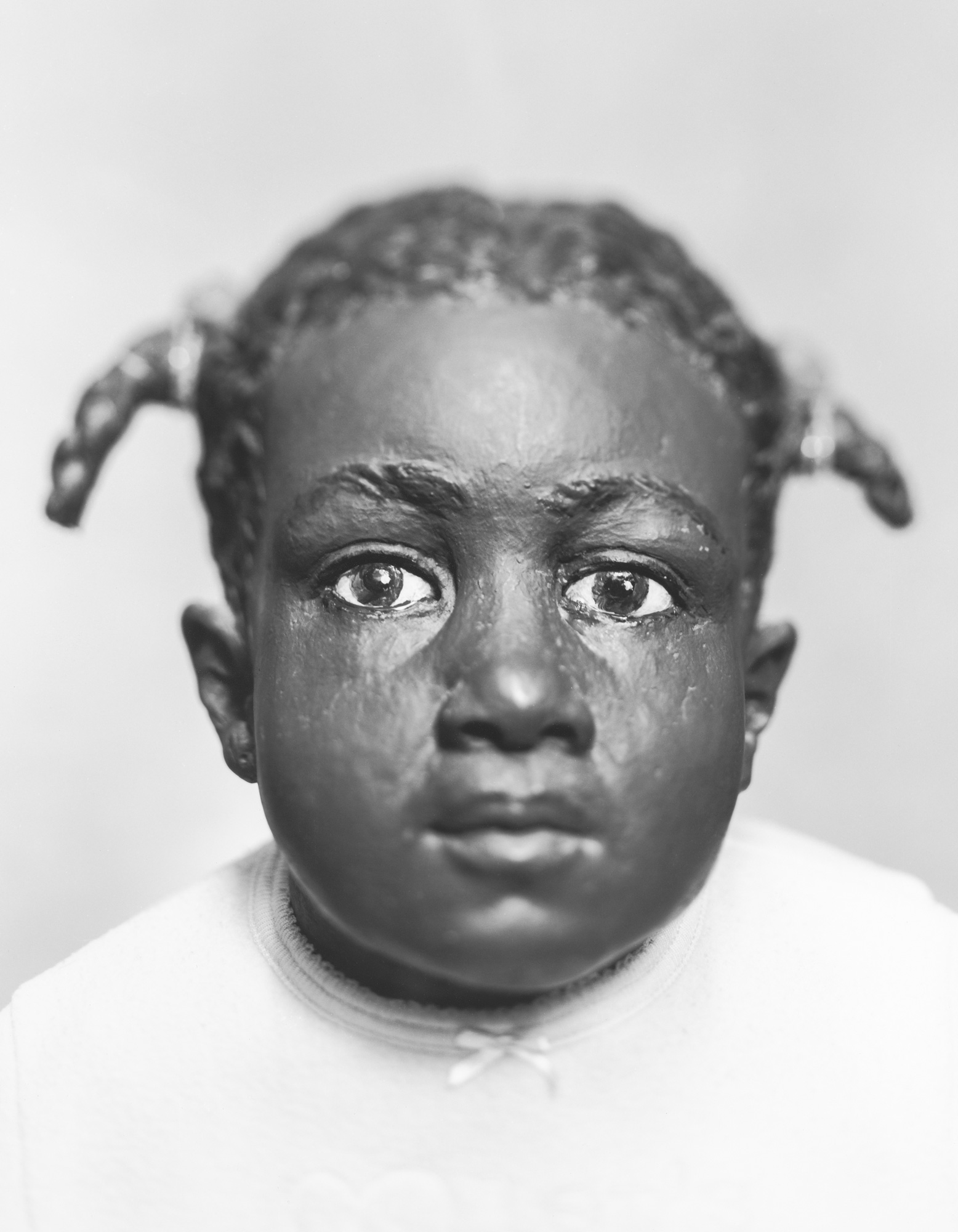

Aliyah Davis. Her stepfather had beaten her to death and dumped her body into the river. The girl was identified only five years after the body was found – by her biological father.

Unidentified boy. The remains of the child were found in 1974. The remains were originally thought to be female, but DNA shows that the victim was male. There are no apparent clues as to how he died.

Jimmy Lee Adams. The body was found in August 2005 in an abandoned funeral home in Detroit. After a year, the body was identified by Adams’ brother from the reconstruction that was broadcast on television. The family thought that Jimmy Lee was buried in a cemetery in Michigan. It is unknown why the body was left unburied.

Unidentified woman. The body was found in 2005. The medical examiner could not determine a cause of death.

Rosella Atkinson. The remains were found in 1988. Two years later, Rosella’s aunt saw her niece’s portrait in a newspaper article about an exhibition of the sculptures at the Mutter Museum, a medical museum in Philadelphia.

Anna Duval. In 1977, the body of a woman was found in a field near the Philadelphia International Airport. She had been shot three times in the head. It was discovered that Anna Duval had left her home in Arizona and traveled to Philadelphia in order to confront John Martini, the man who had fleeced her of her life savings. She thought she was meeting him to get her money back, but instead he shot her. John Martini was sentenced to life in prison.

Yesenia Nungaray. The body was found in 2003. She was identified after three years – with the help of photographs disseminated by the police. The investigators think that Yesenia was murdered.