“No One Will Ever Admit that Their Relatives Persecuted the Jews”: Historians Explain how to Talk to the Genocide Witnesses

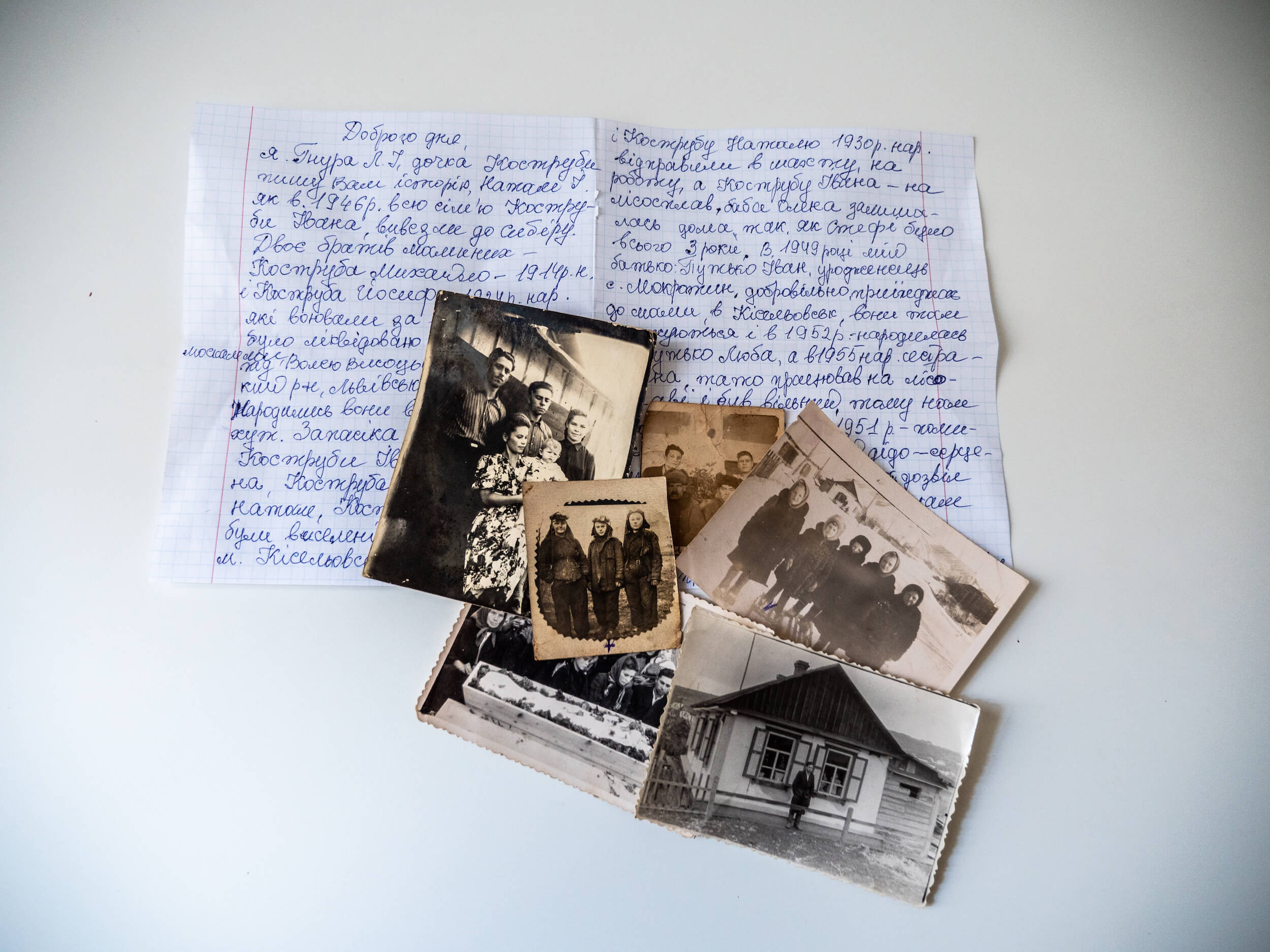

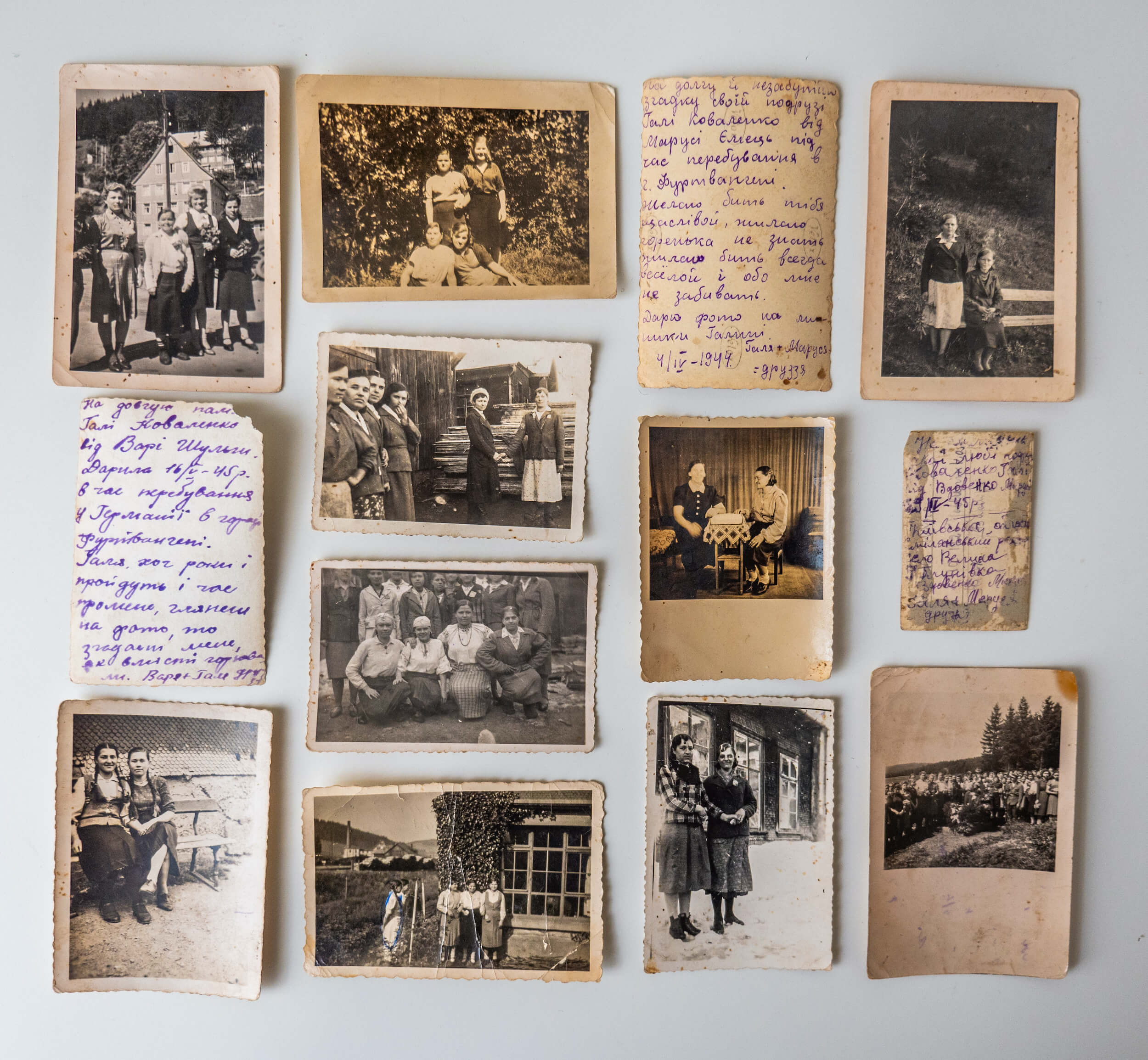

Andrii Usach and Anna Yatsenko, historians and authors of the “After silence”,project, work with oral history. They explore the past by talking to witnesses of social cataclysms — wars, deportations, genocides. They record interviews with people and then compare the recorded evidence with archives. It helps them not only to restore history, but to revive it with the emotions and experiences of actual witnesses.

In the interview with Bird in Flight, the historians talk about the objectivity of their research method, the lies they sometimes hear from the Holocaust witnesses, and why people might change their story every time they tell it.

Let’s start with the basics. What’s oral history?

A.U.: It’s what people tell about their past. But also, it’s a method of documenting their stories. Back in the days, when people couldn’t write, they used to tell stories. Yet, this kind of information transfer became a legit source for historical research only in the twentieth century.

Oral history is a very subjective view of certain events. Still, the more stories we gather, the lower are our chances to get a one-sided, Soviet-like type of history.

How is your work different from what journalists do?

A.Y.: We don’t look for sensational, unique, or original stories. We care about every story, even a banal one. Besides, unlike journalists, we don’t necessarily publish everything that we find. Our goal is to keep all stories safe, even if they all look the same.

What one can learn from these stories?

A.Y.: A lot. We work with traumatic experiences, including World War II, Holocaust, imprisonment in the Gulag camps, Soviet mass deportations, etc. Official documentation gives you plain facts: the number of victims, which city they were deported from, and where they were deported to. But it lacks the details, real emotions, worries, and fears of people who lived through deportation. Imagine a school book that gives you not only dates and places, but actual stories from people who’ve been there.

Why record stories, if they are already available on social media platforms?

A.Y.: On social media, people usually talk about things that are important to them at that exact moment. As time goes by, they reevaluate their experience. When we talk to internally displaced people in Lviv, we tell them there are going to be two interviews — one now and another one after the victory. We need the second interview to find out, whether their expectations have been met, how their plans have changed, and what details have they memorized. One time, we talked to a local woman from Bucha. That was before the occupation, and she mostly spoke about the way Russian soldiers behaved. I guess, we’d hear a different story, if we talked to her now, after the mass killings.

Besides, we ask questions that people rarely think about on their own. Our recordings reveal more details than posts on social media.

Some of your colleagues believe that the war stories should be recorded after victory. What’s your opinion?

A.U.: It depends on the objective. If we collect stories for our archives, then it’s okay. But when we were offered to record a story of a war crime victim, we declined. War crime evidence should be collected by police, international institutions, and journalists, so to be used further in court. We shouldn’t get involved. I mean, we can record them, but we lack the skills and qualifications to collect internationally-recognized evidence.

How do you choose people to talk to?

A.U.: We have two requirements: a person must have witnessed certain events and must be over the age of 18. If a person meets these two criteria, then we are good to go. Recently, we had an interview with an 89-year-old woman. We talked about World War II, she was a kid back then. We had a couple of interviews and between those interviews, the city was attacked with missiles. It made her think of other missile attacks that she heard when she was a kid. She told us that now the explosions sound different and bomb craters don’t look the same too.

What if you suspect that a person is lying? Is there a point to continue your interview?

A.U.: Yes, because sometimes what seems to be a lie might actually be the truth. For instance, during interviews with witnesses, a researcher of Soviet mass deportations Tamara Vronska found out that deported women were not allowed to take their husbands’ last names. That sounded suspicious because she has never heard about that before. So she started digging and found archives that confirmed it.

Besides, witnesses rarely tell outright lies. More often, they exaggerate or conceal information.

Why would they do that?

A.U.: To show a better version of themselves or to fit into the generally accepted narrative. Take, for instance, the Ukrainian-Poland conflict in Volyn, in 1943. A woman told us that she and other girls were taken to a burnt Polish village to harvest the crops. When we asked for details, she said: “Ah, I’ve already told you more than I should”. It means that she got scared that her story contradicts the generally accepted narrative, which states that things like that have never happened.

The same applies to Holocaust. A lot of people will tell you about their relatives who helped the Jews. But no one will ever admit that their relatives persecuted the Jews.

But even if we know that people hide or exaggerate things, we still make a record and analyze it later. Sometimes, analysis can reveal the origins of made-up details. For example, people frequently say that during the Holocaust, dogs were used to chase Jews to the execution points. But dogs are never mentioned in archives. Where do they come from? From movies and books, obviously. People unknowingly include them in their memories.

Apart from checking with archives, what else do you do to confirm witnesses’ trustworthiness?

A.U.: We look at what different people say about the same historical period. It helps us find patterns or inconsistencies.

How do you get people to talk?

A.U.: We have a list of standard questions, which includes their names, birthplace, families, places of living, etc. We ask people if they’ve ever talked to historians or journalists before. We have forty questions overall. But we mostly rely on our feelings, not our notes. We try to adjust an interview to a specific person’s needs. We try to make them feel comfortable, and we use a lot of slang words.

Here is another important point. Your interviewee and yourself might have the opposite view of certain things but that shouldn’t affect your job. Eight years ago, a man from Donbas told us about the Ukrainian soldiers who were driving drunk around the city. We didn’t like hearing those things about our military, but we had to keep recording.

Sometimes people try to drag us into political arguments. They start asking who did we vote for during the last Presidential election. We avoid talking about the subject. In general, you need to show people that their stories are important to you — listen carefully, encourage them, nod, and clarify.

Elderly people frequently devaluate their experience, they think that no one wants to hear their story. Why do you think they do that?

A.Y.: There are many reasons for that. Usually, women are the ones who devaluate their experiences. They say that their husbands can tell a better story.

It depends on the family. The more relatives devaluate people’s stories, the harder it is for historians to persuade them into talking. Sometimes people had to hide their past to protect their kids. It is hard to work with them too.

In Soviet times, people had to conceal their personal stories if they didn’t fit into the official narrative, including the ones about World War II. Unfortunately, we still have a certain historical narrative in modern Ukraine. And if you don’t fit in, you better be quiet.

As in?

A.U.: Well, there is a heroic national version of the World War II events, and people try to adjust their stories accordingly. People rarely tell bad things about the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which obviously had happened in reality. We do have a national historical canon. But surely we don’t use totalitarian methods to establish it, as they do in Russia.

Moreover, the canon can change. Today, Poland supports Ukraine greatly, and it will most probably change the way we talk about the Ukrainian-Poland conflict that happened years ago.

What do you do with the recorded material?

We archive it in a video format and make a transcription. If we know that the person was tagged by the Ukrainian Security Services, we send them a request for a scan of the documents and add them to the story. The Ukrainian Security Services archives are open and available to anyone, not only historians.

Sometimes, we create media projects based on the materials, like, for instance, the “How we survived”

podcast.

How do modern historians use your materials?

A.U.: Above-mentioned Tamara Vronska used our interviews and photos in her book. For their exhibition about the Ukrainian Jews, Augsburg Jewish Museum used our interviews with families, who saved Jews during the Holocaust. We frequently take pictures not only of our interviewees but of the places where it all happened. We sent these pictures to Augsburg Museum too.

What results are you most proud of?

A.Y.: We managed to find a resident of the Ichnia town in the Chernihiv region, who was saved from execution by a Ukrainian family during World War II. He is now eighty-nine and lives in Kyiv. Thanks to him, we reconstructed the history of the Holocaust in Ichnia. Before that, there was no information about the execution of Jews in this town.

A.U.: And a year ago, we found the Komarnitsky family from the town of Turka, who rescued a Jewish woman, Hava Brandelstein. We researched the history of the Komarnitsky family and passed information about them to the Israeli Yad Vashem Memorial. Thanks to our efforts and the efforts of Hava’s grandson, the Komarnytsky family was named Righteous Among the Nations postmortem. It’s an honorary title, which is awarded to those who risked their lives to save Jews from the Nazis. The children of such people even have the right to receive Israeli citizenship.

New and best