Georgiy Rozov’s 10 Favorite Photos

Experience, as everyone knows, is the fruit of errors. At first, everything was going wrong for me too because I was trying too hard. I was invited to a village to shoot a funeral when I was 25 years old. There was only one big room in the small, wooden house, and no furniture. They put the icons and the casket in a red corner. About thirty to forty people were crowding around the casket. One five-hundred watt lamp was hanging from the ceiling. It was dark. I asked to. Move the casket to the street. Refused. I moved back to try to get the whole crowd in the shot, but it was hard to do with a 35mm lens. I leaned back on the oven, sat down. I fixed the sharpness and said, “OK, shooting!” I pressed the shutter, and then there was a terrible crash.

I lost sight of the picture for a moment, and when I saw it again, it was scary and funny – there were no people. The floor had rotted with time and couldn’t handle such a heavy load. There was first-rate swearing heard from the potato pantry, and above all of this nightmarish situation was the casket with the body inside, held up by a few pieces of wood and illuminated by the frightening, five-hundred watt lamp. Unfortunately, I didn’t save the picture.

Shooting from heights. Morning on the Kursk NPP construction site.

Kurchatov is a small town in Kurskaya Oblast. Now, there is a nuclear power plant there, but in the days of my youth, as a young photographer, it was a Komsomol construction site. I had to do some photo reporting on the start of the NPP construction. The trip was like a trial, and my future career depended on its success. If they like the photos, they’ll hire me at Ogonyok.

I decided that we needed to shoot from the top of a crane and do a panorama of the steppe with the trucks in the snow, but the site director didn’t want to be responsible for pictures that would focus on anything negative and he forbade me from climbing up. So, I waited for a lunch break when all the workers would be drawn to the dining area. I climbed the narrow stairs forty meters up with a bag loaded with the notoriously heavy “Zenith E” and a set of other people’s lenses. I was sweating and out of breath. At one moment, I thought that wouldn’t be able to even get all the way up by the end of lunch.

I reached the end of the boom on a narrow track while holding a tethering rope, then fastened the rope to a mounting belt and sat down for a smoke. There was strong wind at that height. After five minutes I felt like an icicle.

The trucks finally came. I had almost gotten the shot I needed when the crane jerked sharply; the operator had returned to work. I flew from the perch and hung in midair, 40 meters up. I grabbed the strap coffer while falling, and it was frightening to think that someone else’s equipment could break.

It wasn’t comfortable to hang like that. The cold makes you feel the need for the simplest things. I began to call for help. The crane operator didn’t hear my attempts for quite a while, and when he noticed he called another worker over. They laughed and pointed their fingers at me for a while, and only later did they manage to get me down. The site director, a cool-headed Armenian, took a long look at me before uttering just one phrase, “So, are you an enthusiast!?”

I got my shot in the end. A vertical strip with two cranes, which stretched a giant ball of a sun from the horizon, was printed in Ogonyok.

Earthmover. A bucket wheel excavator in Stariy Oskol.

They say that people become wise with age and, before taking a risk, they analyze the situation a hundred times over. I absolutely need to agree with this. Thirty years of work has taught me to insure myself more thoroughly than I did at the beginning of my career. And this monster of an earthmover, I shot it while undoubtedly risking a lot. This rotor excavator, six meters in diameter, was running five meters away from me, and I was standing at the edge of a 30-meter pit. The wall of pure apothecary chalk could collapse from a vibration at any minute. Experienced geologists have managed to pull me away from the edge when I was three meters away or insured me with a long rope, but this time there were no such surprises.

A wedding at BAM.

I arrived in Siberia in autumn of 1973, surveying the party of Piotr Baulin. No one would order a helicopter for a young photojournalist, but there was a wedding in the party and Aleksandr Pobozhiy, the main BAM surveyor, needed to go. He brought a white dress for the bride, and black suit for the groom, two cases of vodka and two crates of tomatoes to the taiga.

I couldn’t picture such a wedding occurring today. There was a young cook and a young worker in the party. The director put them in the place for “crimes” and gave them a choice: either get married, or one of them gets fired. He couldn’t afford for there to be any debauchery in the the party. The youths decided to get married.

When the helicopter landed, Baulin himself grabbed the vodka, took it to his hut and locked the door. After the solemn blessing of the young couple, the surveyors were forced to pass through a theodolite according to ancient tradition. Pobozhiy gave the commencement address and left. A banquet was held in the evening. Baulin shared one of the cases of Stolichnaya; each person was given a hundred and fifty grams. The surveyors, however, were acting like adults, singing and fighting.

Nikita Sergeyevich Khryak – determinant.

The largest pig farm in the Soviet Union was built by an Italian team not far off from Nizhny Novgorod. They brought together 250,000 pigs on a small patch of land. They would fatten up the piglets for a month and then send them off to the slaughterhouse. The factory was preconceived down to the finest details, including the reproduction of livestock.

Along the row of narrow cages that were crammed to the brim with female pigs with their tails sticking out, they led the determining boar on a leash like a dog. Whenever he sensed the scent of a female ready for fertilization he rushed towards its tail, but the unforgiving livestock expert dragged it further down the row. The expert wrote down the cell numbers in a small notebook to keep track of the females who would later meet the inseminating boar who, in technological terms, differed somewhat favorably relative to the determining boar. And the poor determining boar was led to the corral for males after passing through the female rows and was in such an excited state that it stood up on its hind legs, seemingly giving a speech on the callousness and treachery of humanity. It was there that I managed to get this portrait.

Upon my return from this business trip, I proudly selected this photo from many others to show off to the management, but they told me that the boar looked a little too much like Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev and that they couldn’t publish it for that reason. Now, I can.

A passing hedgehog – 1978.

A cute, two-pound hedgehog, cast from pure lead and spiked with sharp nails, served as a challenge prize for the farm chairman who was lagging behind the most in one region of Altai. He was awarded it at a grand ceremony where, at the same time, where red flag banners and bonuses were awarded to other leaders.

They feared that hedgehog like the plague. They tried to avoid it by hastily exceeding the plan for delivery of eggs, bread and other food. In those days, the best workers were photographed in front of the honor boards with pleasure. I laughed at their innocent ambitions, thinking that it would be better to reward and punish people with rubles.

Recently I visited the office of a major American company in Moscow. There was a very familiar honor board hanging on the wall with a caption that read, “The best people in our company.”

Again, I ask myself, “Is this photograph really an artifact of a particular era?”

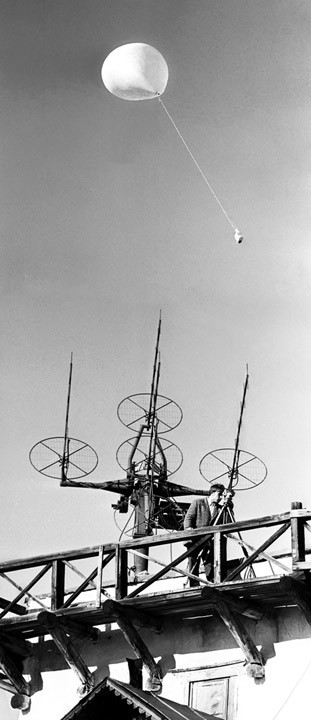

Russian hospitality. Launching a weather balloon in Verkhoyansk. 1975.

Bela Banias was a correspondent in Moscow for the Hungarian journal Orszag Vilag, which was something like our Vokrug Sveta. Bela was very ambitious and always wanted to be the first in anything, for example, the first Hungarian to visit the North Pole. The Hungarians couldn’t retain his photographer in Moscow, so they decided to “rent” my services from Ogonyok.

We met Police Colonel Ivanov, in full order and decked out with medals, at the regional center in Batagai. Having grabbed our things, he took them to a small An-2 which we were going to use to fly the 120 kilometers to Verkhoyansk. As we were going, Ivan Ivanovich told his guest how he liberated Bela’s hometown – where there were beautiful girls, a sea of flowers and most importantly, youth! – from the Germans as a young soldier thirty years ago. Bela plodded along with him, embarrassed. While in the aircraft, he began to say goodbye to the colonel with obvious relief, but Ivan did not even consider leaving his guest, “What do you mean ‘goodbye?’ I’m going to personally show you around,” he said as he hoisted the Hungarian up the ladder.

A full table was waiting for us at Verkhoyansk. Colonel Ivanov showed us a local stable of horses that could handle a minus-50 degree frost and then took us to the horse milk factory. He poured us a couple of glasses of kumys (horse’s milk), showed us how to milk a horse and how to ride an old nag.

The meteorologists in one of Siberia’s oldest weather stations (at that time it had been around for a hundred years) launched a weather balloon and talked about their life and times.

At the end of the day, Bela was supposed to get an interview with the chairman of the city council, but this would-be conqueror of the North was behaving very strangely. He sat silently in the mayor’s office, hanging his head. An awkward silence permeated. Banias wasn’t well; he was green right up to his eyes, and probably from the Yakutian kumys.

“Excuse me, can you tell me where the bathroom is,” he asked, interrupting a painful pause.

“I’ll take you,” said the colonel.

Twenty minutes later, the office door flew open and in came a smiling Ivanov followed by a green Bela.

“Can I check in to a hotel,” whispered the suffering journalist.

The hotel had two rooms available. “After you,” Ivan Ivanovich said, opened the door to the suite. The guest, however, turned and ran to the standard room.

When we were alone, Bela sadly summed up the results of our day. “You know,” he whimpered, “I don’t think I did anything wrong to deserve being taken to the toilet with a police colonel!”

We didn’t meet with Ivan Ivanovich in the morning. He was insulted and left on the only helicopter in the town, which on the previous day was waiting to take us on a true northern hunting expedition.

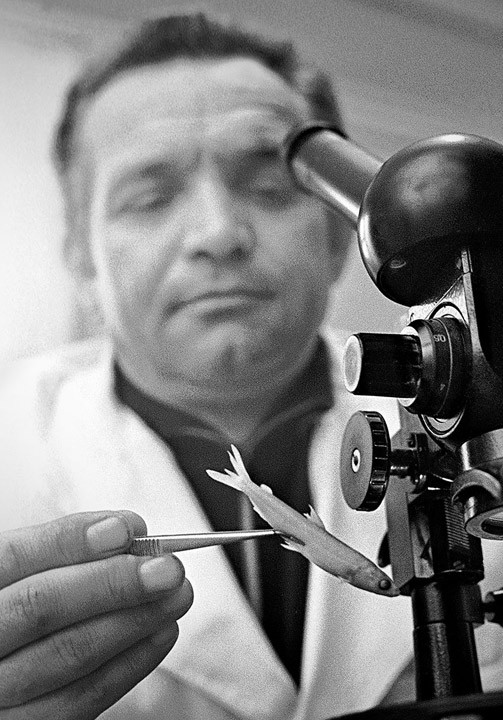

An ichthyologist at a tractor factory with young white fish.

The whitefish got its name from the fact that it spawned in the Bashkir White River and fed into the Caspian Sea. Seventy years ago it was valued more highly than sturgeon.

The Volga Dam along with the Volgograd hydroelectric station ruined this royal fish. The fish swam up the Volga, rested along the barrier of the dam and were forced to lay eggs somewhere around there, near the hero city. The conditions for survival were not suitable for the eggs; whitefish need a rocky bottom and strong currents, but the water near Volgograd has a sandy bottom and the water is tranquil.

In the seventies, the authorities realized that this valuable fish was threatened with extinction, so they built a small fish-breeding factory near Astrakhan where the fertilized eggs of fingerlings were grown. They say that only two out of a hundred survived to reach sexual maturity, but experts were convinced that the self-reproduction of whitefish had ceased forever and that the population of the species was preserved only through their efforts.

One winter I went on a business trip to the Volgograd Tractor Factory. They had asked the resident ichthyologist to accompany me through the plant (the factory cared about the environment and contained an ichthyology laboratory). In the evening, he told me about how he prevented the complete extinction of whitefish for three bottles of vodka.

The Volga freezes in winter. Sometimes, plant workers had to blow up the ice in order to carry out any work done at the bottom. According to their instructions, they were supposed to invite the ichthyologist in such cases so that he could examine the reactions of the fish for scientific purposes. One time he caught a stunned whitefish fingerling. It was a sensational finding; self-reproduction at that time could be considered proven. Spawning could only be possible in one place, directly underneath the dam where there was a particularly strong current.

The scientist was a realist and didn’t report his finding to the authorities. At that time they were building an artificial breeding ground for sturgeon in the town. The authorities decided to teach a stupid fish not to lay eggs on the right bank of the Volga, but on the left bank, where it had never done it before. Barge after barge poured gravel into the shallow water with no second thought for expenses. It was clear to the scientist: money was being wasted, but no one would listen. So, he talked to the captain of the barge about his idea. For three bottles of vodka the captain agreed to empty three barges’ worth of gravel under the dam that were originally intended for sturgeon spawning. Since then, the whitefish have had a real, natural maternity ward.

A story from Brest. Love.

Invited veterans flocked to the Brest fortress and museum in 1975 for the thirtieth anniversary of Victory Day. On the evening before the holiday the memorial was empty. From a distance I saw the figure of a lonely woman with a lilac bouquet in a milk bottle. She walked along the engraved names in granite. When I ran up to her, she was already kneeling and weeping bitterly.

In those years it was discussed in the photo media in every which way: does a photographer have the right to shoot with a hidden camera? Is it moral or not? I was a perfectionist at that time and considered it to be moral because an orchestrated picture ceases to be a document of history and becomes seemingly fake. On the other hand, who gives photographers the right to invade another person’s life?

In any case, I took a shot of the widow of Private Ryabov.

She fell in love with a villager as a young woman. She became pregnant, and later her spouse was drafted into the army. She wanted to give birth next to her husband by any means necessary, so she went to Brest, where he was stationed, against the best wishes of her relatives. She gave birth in a military hospital a few days before the start of the German offensive. On the night of June 22nd, 1941, her husband went AWOL so he could see his son. Two hours later, the Germans had already taken the hospital island. Enraged German soldiers shot all the men present, and she watched one of them shoot and kill her son.

She didn’t remember what the underground was like. Some patients were hiding there and miraculously survived, and a few days later they decided to swim across the canal at night and go in pursuit of our retreating troops. She became a nurse two months later and served until victory.

At the end of the war, it became clear that her husband wouldn’t return. She married another soldier and gave birth to three sons, but her first love was never forgotten.

On the eve of Victory Day in Brest, her husband finally let go of her, and she cried.

Aquatic.

The streets were not made for kissing some 25 years ago in Moscow. Once by chance, during a night of shooting, a young couple came along into a very architectural frame and glued together. Somehow, the idea came to me to start taking pictures of kissing couples. I put a picture up on a photo website and offered anyone to participate in a series called “Moscow for Kisses.”

No one responded for about two months, but then suddenly it blew up. Young photographers came with their girlfriends. On one of the first shoots we settled on the Sofiiskaya bank, directly across from the Kremlin. Passers-by made jokes and offered to help us. One guy was ready for a kiss while swimming in the Moscow River. I thought he was joking; it was April and the water was ice-cold! But he undressed and jumped into the water. The guy was very drunk and you could smell it, and we couldn’t get a true kiss out of him.

The “Moscow for Kisses” series was soon published in Ogonyok, Moskovskiy Komsomolets, Moskovskie Novosti, and several other publications, with a total circulation of several million. Later, they showed on TV how I was shooting kissing couples in the underpass near the metro at Krasnaya Presnya.

Since then, kissing on the streets in Moscow has become normal. Kissing, in fact, is now everywhere: in the subway on the escalators, in shops, at exhibitions, etc. Setting up a photoshow is no longer necessary. I still shoot kissing, but in the old-fashioned way that is photojournalism.

The wettest kiss. Passion.

At the Sheraton Hotel in Egypt, I took one out of three hundred total kissing shots. A couple from Moscow had retired to the jets at an artificial waterfall. I showed them what I got and then they even started posing for me with great enthusiasm. The first shot, however, was the most passionate.

New and best