In the 1960s Nikolai Bakharev worked as a locksmith at an ironworks while shooting people on the beach in his pastime. Today his photographs are courtesy of museums and private collections in Russia and the US. At the end of 2014 Bakharev was short-listed for the prestigious Deutsche Börse Photography Prize. Bird In Flight asked Nikolai about the nominated ’Swimmers’ series, why people shouldn’t call him ‘The Russian Helmut Newton’ and what made him give up portraits for the sake of landscapes.

In the Soviet Union there was a penal code article for Parasitism to punish those who skulked work. That’s why I worked as a locksmith at a factory and on weekends took pictures of people on the beach. I didn’t think I had any particular talent, photography was more of a hobby for me, but I felt like this was what I should do for a living.

‘Swimmers’ series was nicknamed this way by journalists as an allusion to classical paintings, but in fact all the beach photographs belong to a body of work called ‘Relationship’. It was important to me to show those open, natural relationships that could be observed in unsophisticated poses, in a attempt to show the warmth appropriate for a public display. What was captured on film was the relation of people on the beach to me, my relation to them and their relationship with one another. And the beach itself with its bathing costumes was secondary, it just served to help the subjects relax and be at ease.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_01.jpg”, “text”:”From ‘Relationship’ series, N°14. 1980. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Photography © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev” },

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_02.jpg”, “text”:”From ‘Relationship’ series, N°5. 1985. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Photography © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev” },

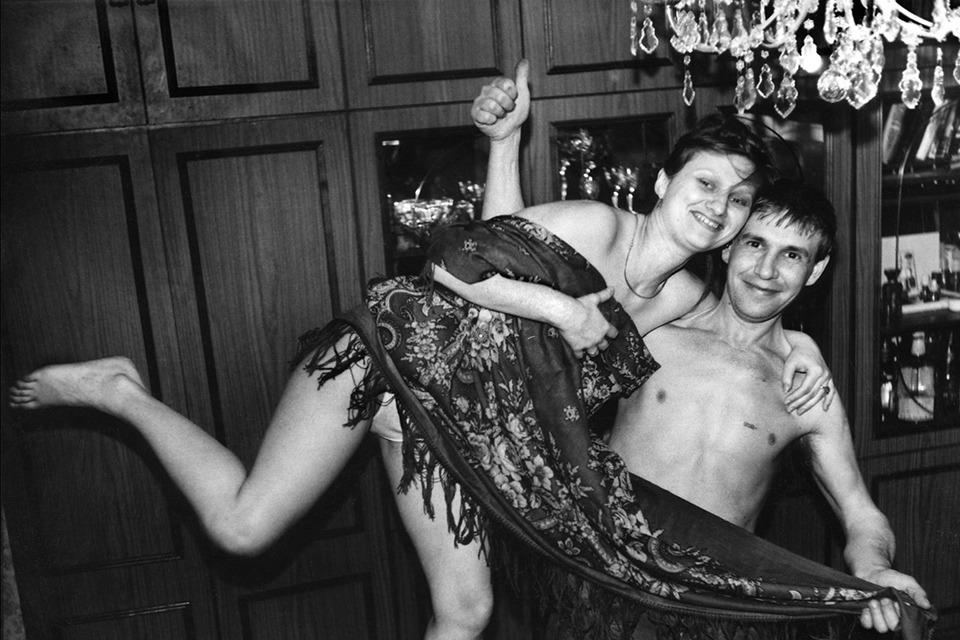

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_03.jpg”, “text”:”From ‘Relationship’ series, N°51. 1991-1993. Gelatin Silver print. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Photography © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev.” }

Some of my clients from the beach — those who liked my style of work, later agreed to pose at home. That’s how ‘In the Interior’, ‘Together’, ‘The Couch’, ‘Entertainment’ and other series were created. The photo shoots – up to six hours long – produced very special relationships that resulted in something totally different from what ’The Soviet Photo’ magazine was teaching. Because it was my clients who ‘imposed’ the themes of photographs on me, not vice versa. Those themes revealed their ideas of what they wanted to remain ‘in a long memory’. My task was just to aesthetically put the right things in the right places and do a clever lighting. As a result I accidentally arrived at the degree of intimacy that was banned from fine art as something primitive and almost vulgar. No matter if in literature and cinematograph such scenes are very common.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_10.jpg” }

The degree of close-up-ness, openness and intimacy observed in my models would often make the beholder wonder about my working technique. About a very special relationship between the photographer and his models who allow this degree of openness. Gradually I realised that only by ignoring the conventional ideas of what is acceptable and what not, by breaking the bounds of the the conventional, one can achieve a truthful and convincing portrayal. But in order to make the models get over their shyness and rigidity, feel at ease during the shooting process, and forget about conventional morality, they need to establish a confidential, even intimate relationship with the photographer. And the photographer, to my mind, should not try to avoid this intimacy. Because it is an important part of his work.

The customers were often unhappy with the results of the nude shoot, even if they were not afraid to see their ‘improper’ photos in the media — this theme was totally banned in the Soviet Union. But the KGB agents were interested in the people who deemed they could afford this degree of intimacy. Mainly because of the fact that there were foreign agents in the city with whom the ‘degenerate’ girls could have a relationship with. But since my ‘clients’ did not use their inclinations for illegal purposes, I didn’t have any major problems with the law enforcement. I did not charge my models for nude photo shoots, which, in a way, protected me from being charged with pornography – anything naked could be considered pornography at that time.

I became interested in photography exhibitions back in the 1970s. At that time exhibition-contests were very common all over the country, ’Soviet Photo’ magazine had a whole section to inform about them. In 1972 one of my beach photographs that had been commissioned earlier (’Type’ N°161 – Child) was accepted for the All-Soviet exhibition held in Shostka.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_12.jpg” }

Another photo with a young couple romantically holding hands that I later nicknamed ‘Cartoon’ N°1, was rejected for no known to me reason. After that I gave up the idea of sending my photographs to competitions as unworthy of the noble name of ‘real art’. Only in 1987 an All-Soviet photo exhibition dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the Revolution ‘opened its doors’ to photographs with social themes, so some of my works were included in the show.

It was only possible to be a freelancer for members of creative unions, those who internally and externally complied with conventional definition of art. For them the social aspect of life was of no interest. As for me, I did not see any spirituality so much sought after by members of creative unions, in the faces of my subjects, and that, in spite of myself, filled me with disbelief as I was looking through portraits shown in magazines, photo books and exhibitions. But work is work, so as I was shooting in kindergartens, schools, at weddings and funerals, I became sensitive to a different kind of spirituality that corresponded to the idea of photo journalism. I was also reading the Photorevue, a Czech magazine that published varied photo content and articles on different aspects of photography. It taught me to take my job more seriously than that of a service staff.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_05.jpg”, “text”:”From ‘Relationship’ series, N°7. 1985. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Photography © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev” },

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_06.jpg”, “text”:”From ‘Relationship’ series, N°70. 1991-93. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Photography © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev” },

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_07.jpg” }

40 years ago I was using Fotokor’(90×120), FED (24×36), Iskra (60×60), Kiev 60 (60×60) with shutter speeds from 1/30 to 1 second. Those cameras taught me observation and patience for capturing what corresponded to my idea of ‘real’. How, by means of what young photographers nowadays can break free of banalities? They don’t observe, don’t try to find – among all the faces that surround them – something of their own, something convincing enough to confirm their identity as artists. Modern equipment does not suggest long observation of someone or something. It is good for continuously fixing an ‘object’ and, knowing the photo editor’s taste, choose the necessary image. I, personally, now also use a digital camera – it frees me from excessive manipulations for getting the right result.

In the last 7-10 years trips to the beach did not bring me any income or artistic achievement. The public now thinks it is cheaper and easier to do a phone selfie, and it is getting increasingly unsafe to stalk people with a camera, and besides, I am not so young to be able to make friends easily and communicate with people in the ‘creative’ way.

This is why for the last four years I’ve been working with landscape: an attempt to see human psychology was replaced by an attempt to feel and convey the uniqueness of a natural habitat. Luckily now in my town there is an amateur photographer Mikhail Yurievich Alabugin: he is an electrician, but well, he sees the landscape in a very special way, an artist’s way. Me, who has worked my whole life as a photographer, as I am walking by his side in the forest, I am unable to reflect my perception of the outside world through a landscape. But an electrician with 30 years of experience as an amateur photographer has convinced me that professional artisan skills don’t always and necessarily matter. There should be something else in the head of a creative person.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_04.jpg” }

What journalists so often ascribe to me is, in fact, their own subjective vision that has more relevance to their own world than to me and my work. I don’t think there is much in common between my work and me that of Helmut Newton because, after all, Newton worked for commercial magazines and hardly needed to concentrate that much on human psychology. Some common traits can of course be observed – but they are very formal and are mostly due to the fact that the work is all around nudity, that’s basically where the similarity ends.

Issues of sexopathology, the way I understand it, are more related to an assessment of one’s sex life from the viewpoint of norm and pathology. As for me, I am more interested in capturing some psychological states and conditions, including those that are sex-related. But I don’t give an assessment or put labels on my models, I don’t try to find out what’s wrong with them and their sexual behaviour. What beholders so often make up has more to do with their own perception rather to what is shown in my photographs. If social-ness is understood as something other than just a by-product of glamour-commercial understanding of reality, then yes, I am a social photographer.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_09.jpg” },

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/baharev_08.jpg” }