Robin Laurence: “The Greatest Challenge Of Photojournalism Now Is To Simply Carry The Work”

Opening the Photography Oxford Festival this fall, its founder Robin Laurence said that his ultimate goal is to increase the value of photography to the level of painting, sculpture and other visual arts. Laurence has more than 45 years of experience in photojournalism – he got his first job at The Guardian at only 24 years old. Later he worked with The Times, The Washington Post, Forbes and Business Week; organization of the festival, which included dozens of exhibitions, film shows, workshops and roundtable discussions took two years.

Bird In Flight’s correspondent met Laurence in Oxford and talked with him about how photojournalism has changed over the past decades, why photography needs to prove itself as art, and what is good about it.

How did you start doing photojournalism?

While I was still at school my last year my father gave me a camera. I didn’t know how to use it, so I joined a camera club. And at the club there was a guy who took great pictures, but always turned up late for the meetings. In the end I asked him why he was late and what had he been doing. He’d been on a local murder hunt or following a fire engine – he turned out to be a news photographer. And that sounded quite exciting to me. I asked him how he became a news photographer and he said, “It’s very simple, you put your camera on the back of your car and you follow an engine with a blue flashing lights.”

I kept my camera with me all the time and amazingly the very next week at this camera club at the end of the meeting I drove out of the club and the were two fire engines behind me. I thought it was amazing! I pulled in and let fire engines to pass and then tried to follow them. I said “tried to follow” because I had my very first car, Morris Minor, which at the best of times did about 37 miles an hour going down hill. I attempted to give a chase, but I could see the blue lights getting further away in the distance. And as I followed the blue lights, they got closer and closer to the village where I lived, and then we got to the outskirt village where I lived. I began to think, supposing someone I know is in trouble, supposing my friend’s house has been burned down or been in a terrible accident. Then fire engines got to the end of the road I lived. Outside of my house already was the fire engine, ambulance, police car. I followed fire engines to my own house which was half burned to the ground.

I didn’t take any photographs because I was too shocked, but there was something about being where the news happened. Being there rather than reading about it the next day. And that, I guess, developed my interest in journalism. I wanted to be where things happened. I wanted to understand the world first hand rather than through reading newspapers. I wanted to write newspapers and take the pictures.

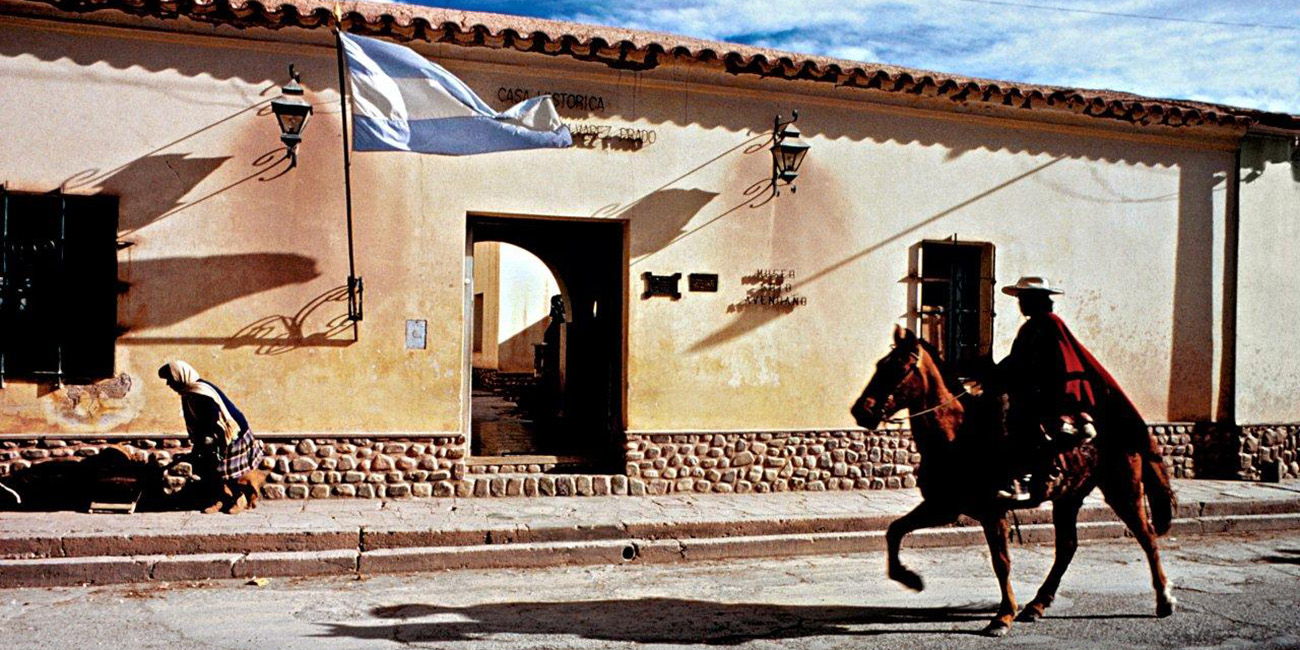

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_01.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 01”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_02.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 02”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurance_cover.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 03”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_03.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 04”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_04.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 05”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_05.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 06”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

}

And you were successful. You started working for The Guardian as a journalist and photographer.

Yes, and I enjoyed it very much. The Guardian was very keen on photographs and also wasn’t interested in the predictable pictures. For example, if the president whatever came to visit our prime minister, most newspapers would want the photograph of two politicians shaking hands. But not The Guardian. The Guardian was looking for something more interesting, something with a little bit of wit, something that said the same thing, something that said that the president whatever had come to visit our prime minister but with a bit of content underneath. That was one of the things that really convinced me that The Guardian was the place I wanted to work.

But later on you decided to become a freelancer. What were you looking for? Was that a professional freedom and independence?

No, that wasn’t freedom. I was obliged to do that because back then the unions didn’t allow anyone to do two jobs. And I was taking photographs and writing copy. The union said, “No, you can’t do that. You are taking somebody else’s work away.” I missed the camaraderie, being a part of the team. But in those days I was very kin to both write copies and take photographs.

The Guardian was my favorite magazine to work for because of the kind of photography they were looking for, and they used pictures in a very big size – that was another attraction. I enjoyed working for Business Week and Forbes, I did mainly portraits for them. We were shooting in color for Business Week and Forbes and color was a completely new experience for me. But looking back, the greatest pleasure I had in taking pictures and probably the greatest pleasure in writing was in work I did for The Guardian.

You have published three books. Which of them is the most important for you?

It was interesting to work on a book about birthday presents – it was a researching job, looking for all the most unusual birthday presents that changed hands between celebrities. That was good fun to do, hard work and quite different from taking photographs. It gave me a necessary break at the time from photography. And that was kind of challenge too. I set myself a task to find 365 unusual birthday presents. So finding first 200 wasn’t very difficult, but then next 165 were very difficult to find. Sometimes I would spent a whole day or two days looking for the right present and not find anything I needed. Sometimes I thought I’d never get to finish this. But my favorite book was definitely the book of Islam.

Are you writing something at the moment?

At the moment? No. Before the festival I started working on a new book about the relationship between photography and politics. I’m very interested in the way that photojournalism both enforces and possibly influences the political process. But when the Festival came up I had to postpone it.

Is it difficult to combine photojournalism and writing?

Yes, it is. I always had to stay double focused. The first thing I would do is to decide in my mind where the story picture laid or where the words story laid – what is going to be more important.

If I was doing an interview or a profile of politician, I would consider that the words were more important because everybody would know what that person looks like.

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_06.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 07”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_08.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 08”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_09.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 09”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_10.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 10”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_07.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 11”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

}

Of course a photographer wants to put his own vision, his own reflection, in his work. For example, if I was to take a photograph of somebody very famous, somebody who’s been photographed plenty of times, I still want to put my impression to it, but it’s very important that the author doesn’t work for himself and makes the image that’s the true reflection of the subject.

But even true photographs can be cropped or manipulated in order to have the desired effect.

There is absolutely no doubt that the spin doctors, the people who looked after the politicians, are very wise to use the power of pictures. They do all they can to ensure that their politicians are looked after and shown in a good light in photographs. Now sometimes this is done in a very straight forward manner. But sometimes they go to considerable length to create a picture that will win over the electorate photos in a less than honest way. And that worries me a lot because I think that photographs are very powerful.

The photography took over from painting as our eye witness to history. We rely on photographers now to be our eye witnesses, as years ago we used to rely on painters. The danger is when the pictures are manipulated so much the public no longer believes photojournalism because the public understands that it is so easy to manipulate pictures.

Then should who take the responsibility for that – the journalist, the editor or the publisher?

I think the greater responsibility lies on a publisher and editor. I’m saying this a photojournalist myself. I had learned to react very fast in the situation. Sometimes, reacting too fast and following the action you can’t think carefully about the whole story.

But the other thing you need to remember that the photographer can move his camera just five degrees and the resulting picture can tell a completely different story, move the camera back ten degrees and the story changes again. So it’s not just manipulation after the picture been taken, it’s how the photographer has seen the event.

As a hard news photographer your job is to record. It’s not your job to be creative; the creativity is appropriate when we need to show the very ordinary situation and then it’s a photographer’s job to find something extraordinary in the ordinary. But not in hard news. In hard news you have to record story as dispassionately as possible.

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_12.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 11”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_11.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 12”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_13.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 13”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_14.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 14”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/laurence_15.jpg”,

“alt”: “Robin Laurence 15”,

“text”: “Photo by Robin Laurence”

}

How can one protect himself from such manipulations?

You have to ask yourself whether what you’ve seen can be true. For example, Mr.Putin is an extremely good example of having instigated a very aggressive public relation campaign with photographs of himself. The series of photo opportunities set up with Mr.Putin were extraordinary; the photos where he was on horse back, swimming in cold water, et cetera. But the most extraordinary picture was the one suggesting he’d been diving to look for treasure. (In August 2011, Vladimir Putin was scuba-diving in Taman Bay – Editor’s note.) So he went off the diving boat in his diving gear and miraculously, within 5 minutes, found a priceless treasure. Now I think that was where spin doctors went too far. Even the simplest reader would say, “Hold on, for 5 minutes he was underneath the diving boat that could not be true.” But I suppose that the less educated people are the more chances you have to persuade them with pictures.

How do you think photojournalism changed over last decades?

I guess the biggest change has been in the last 15 years with digital technologies coming. It has brought the citizen journalism because everyone has some form of camera. We, the professionals, were thinking it’s a good thing to start with because whatever happened and wherever it happened you would have someone on the spot. But it didn’t work out as we expected. Mainly because it was very difficult to check the veracity and honesty of the pictures. Not surprisingly, the citizen journalist was perfectly confident to hold straight cameras in front of burning building, for example, but when it came to making pictures behind the headlines, they were lost. That is something that the professionals know how to do.

In fact, if you take a look at any newspapers today and count the number of hard news pictures compared to feature pictures or portraits, the hard news pictures are still in minority. So there still is a need of professionals to take the portraits of the politicians, celebrities, bankers, need of the professional to go behind the scene to take those “telling pictures” in hospitals and so on. So digital technology has not contributed in news quite as much as we though it would.

But there’s one thing I don’t understand. About 35 years ago there were two or three magazines in the champion news photography – one was Life magazine which was the American publication; in Great Britain we had Picture Post which was also photography led. These magazines had a huge number of followers during the Second World War and immediately afterwards. And then for some reason (which I have to say, I don’t understand), they died out. The easy answer was the coming of television, that people were getting illustrated stories from televisions and they didn’t need magazines anymore. I think that’s partly true. But they died very quickly and it is very difficult to understand.

So what do you consider to be the biggest problem?

The biggest problem now is a lack of appetite for photojournalism among newspapers and magazines. They prefer pictures of fashion, portraits, celebrities, and so on. They believe that that is what their readers prefer. And also, those pictures are far less expensive that news pictures.

Unfortunately, as you know, newspapers are losing money. They all have online versions of their papers of course, but strangely the photographs do not raise the same interest online as they do in print. Research done in America showed that people are not drawn to printed and digital photographs in the same way. So for some reason images online are not having the same effect.

The greatest challenge of photojournalism now is simply to carry the work. Otherwise editors will need to use PR materials. We already know that a great deal of text comes from public relation agencies or PR divisions of the government or business. And that’s likely to happen with photography as well.

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_01.jpg”, “alt”: “Laura El-Tantawy, «A Woman Wears the Hijab» («In the Shadow of the Pyramids» series)”, “text”: “Laura El-Tantawy, «A Woman Wears the Hijab» («In the Shadow of the Pyramids» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_02.jpg”, “alt”: “Joanna Vestey, «Bob Wyllie, Head Porter. Rhodes House» («Custodians» series)”, “text”: “Joanna Vestey, «Bob Wyllie, Head Porter. Rhodes House» («Custodians» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_03.jpg”, “alt”: “Maisie Broadhead, «Speaking at a Machine» («Broadhead’s Women» series)”, “text”: “Maisie Broadhead, «Speaking at a Machine» («Broadhead’s Women» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_04.jpg”, “alt”: “Drew Gardner, «Charles II» («The Descendants» series)”, “text”: “Drew Gardner, «Charles II» («The Descendants» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_05.jpg”, “alt”: “Mark Laita, «Blue Malaysian Coral Snake» («Snakes» series)”, “text”: “Mark Laita, «Blue Malaysian Coral Snake» («Snakes» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_06.jpg”, “alt”: “Clarita Lulić, «Sunset Beach – Kiss» («Seven Short One Long» series)”, “text”: “Clarita Lulić, «Sunset Beach – Kiss» («Seven Short One Long» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_07.jpg”, “alt”: “Robin Hammond, «Alice» («Inside Mugabe’s Zimbabwe» series)”, “text”: “Robin Hammond, «Alice» («Inside Mugabe’s Zimbabwe» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_08.jpg”, “alt”: “Espen Rasmussen («On Solid Ground» series)”, “text”: “Espen Rasmussen («On Solid Ground» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_09.jpg”, “alt”: “Mariana Cook, «Aung San Suu Ky» («Justice» series)”, “text”: “Mariana Cook, «Aung San Suu Ky» («Justice» series)” }

How did you come up with the idea of the Photography Oxford Festival?

First of all, I wanted to bring world class photography out of London and into the regions. There is plenty of good photography in London, but in the regions it’s quite difficult to access it. The second motive was that there were lots of issues around photography at the beginning of 21st century that need quite careful academic study. It affects our life in so many ways, but I don’t think we think carefully enough about it. And about the effect that photography has on our lives. I thought Oxford would be a good place to begin looking at that as there a lot of good brains in Oxford. And thirdly, I was always disappointed about the level of awareness and appreciation of photography compared to other visual arts. We in England seem to enjoy painting and sculpture, but when it comes to photography for some reason it remains underrated. And I thought the festival might be a good place to start to give photography a leg up.

The main question, discussed on the festival was “What Good is Photography?”. Did you find the answer?

We had a final panel discussion looking at what good is photography and yes, we have some answers. First of all, it very quickly became very clear that photography has a great deal of good in many ways. For example modern medicine, science, a lot of education could not function without photography. David Hockney (English painter, designer and photographer, pop-art representative, one of the most influential artists of 20th century — Editor’s note) even said that even the history of art could not function without photography.

A much more interesting question was whether photography can raise the spirit like other arts. Whether people are able to engage with photography and feel an emotional kind of reply in the same way that they might feel in the presence of great painting or listening to music, reading poetry. I think some people thought it was possible that photography can do this. And some people express the idea that because there was a piece of mechanical equipment involved that got in a way of a kind of pure emotional reaction. They seem to feel that with a painting it all comes from the artist. And because everybody has a camera now, if they see what we would consider as work of art in photography, many people are very likely to say, “I could do that. I just don’t have a right equipment, I’ve only got a cheap camera.” They believe that it’s all about the equipment. They think that photography is a little bit further on from what they able to do because of the equipment the professional has.

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_10.jpg”, “alt”: “Rory Carnegie, «Dolly and Nora» («Port Meadow dogs» series)”, “text”: “Rory Carnegie, «Dolly and Nora» («Port Meadow dogs» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_11.jpg”, “alt”: “Bernard Plossu, «Nijar»”, “text”: “Bernard Plossu, «Nijar»” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_12.jpg”, “alt”: “Wendy Sacks, «Brothers» («Immersed in Living Water» series)”, “text”: “Wendy Sacks, «Brothers» («Immersed in Living Water» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_13.jpg”, “alt”: “Arno Minkkinen, «Mouth of the River Fosters Pond»”, “text”: “Arno Minkkinen, «Mouth of the River Fosters Pond»” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_14.jpg”, “alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti, «Solovki, White Sea»”, “text”: “Pentti Sammallahti, «Solovki, White Sea»” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_15.jpg”, “alt”: “Richard Davies, «Podporozhye» («Wooden Churches» series)”, “text”: “Richard Davies, «Podporozhye» (series «Wooden Churches»)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_16.jpg”, “alt”: “Susanna Majuri, «Winter»”, “text”: “Susanna Majuri, «Winter»” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_17.jpg”, “alt”: “Shahidul Alam, «Noor Hossain mural in campus» (series «A Struggle for Democracy»)”, “text”: “Shahidul Alam, «Noor Hossain mural in campus» (series «A Struggle for Democracy»)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_18.jpg”, “alt”: “Matthias Heiderich («Reflexionen Eins» series)”, “text”: “Matthias Heiderich («Reflexionen Eins» series)” },

{“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/oxford_19.jpg”, “alt”: “Yann Layma («Butterflies» series)”, “text”: “Yann Layma («Butterflies» series)” }

How did you choose photographs for exhibitions?

We have decided not to have a certain theme on purpose because we thought a theme from fist festival might exclude some potential visitors who are new to photography. I wanted to attract people who haven’t thought of photography as an art before. I wanted to give them really good choice.

There was a number of questions I wanted to ask at the festival. One was about manipulation – the exhibition was called “Design to Deceive.” I was also interested in how NGO photography developed – we looked at the evolution of Oxfam‘s photography from 1950 to the present day. I was interested in how photography is used to portray both hunger and poverty, and again whether we’ve been properly informed by NGOs through the photography.

We also had an exhibition that was called “Photography as Souvenir.” Photography became the essential souvenir from the holiday, it became a goal of a holiday.

We had exhibition of photojournalism which we kind of connected to DTD to get people to think about what they see. And on top of that I became very interested in Finnish photography. They have turned out some really remarkable photography for the last of 20 years. So we showed four Finnish photographers as a kind of celebration of their work.

What was your favorite project?

There was one photographer whose works I enjoyed the most. He was one of the Finish photographers, his name is Pentti Sammallahti. He does wonderful black and white landscapes which include animals. The way he draws the position between the animals and landscape is so extraordinarily perfect in term of composition and timing it makes his pictures the most extraordinarily moving that I have ever seen. There is not a picture of his that I have not found myself dwelling on for a few minutes. And sometimes in ten minutes time I couldn’t put the picture away, I was so drawn to it. So there is no doubt Penty Samalaty comes out as number one.

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/pentti_sammallahti_01.jpg”,

“alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti 01”,

“text”: “Photo by Pentti Sammallahti”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/pentti_sammallahti_02.jpg”,

“alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti 02”,

“text”: “Photo by Pentti Sammallahti”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/pentti_sammallahti_03.jpg”,

“alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti 03”,

“text”: “Photo by Pentti Sammallahti”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/pentti_sammallahti_04.jpg”,

“alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti 04”,

“text”: “Photo by Pentti Sammallahti”

},

{

“img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/pentti_sammallahti_05.jpg”,

“alt”: “Pentti Sammallahti 05”,

“text”: “Photo by Pentti Sammallahti”

}

What are you planning to do now?

I sincerely hope that with my colleges I will be able to produce the festival every other year. I’d like to think that during months between festivals we can continue to have some talks and discussions, looking at the issues around photography in modern society. I think they are important issues and they need serious discussions.

New and best