Yana Romanova: “I Talk About Things That Haunt Me”

One month ago, Yana Romanova started a crowdfunding campaign to collect money to publish a book dedicated to her most famous project, “Expectation.” At Bird In Flight’s request, Elena Gorshenina spoke with Yana about what questions she pondered as a child, what an objective photo is, and how to keep distance.

Born in St. Petersburg. Taught at the Yu. A. Galperin department of photojournalism at the Union of St. Petersburg journalists from 2011 to 2013. Curator of the course, “The Power of the Medium” in the education program at FotoDepartment.Institut. In 2014, the British Journal of Photography included her in its yearly list of 25 photographers to follow (“Ones to Watch”), and The Calvert Journal put her on its list of 25 photographers who are changing impressions of Russia. Prizes awarded by Discovery of the Meeting Place, International Photography Awards, and Photography Book Now by Blurb.

I'm a naive person and I often don't understand things. I grew up as a recluse and I was even afraid to go out in the street as a child. Until I was 16, I was too afraid to go to the store and ask the salesperson for something, so I went to the supermarket instead, where I didn't have to speak to people. It was a condition where you don't know anything about the world or obvious things like family, beauty, nationality, etc. For any of my projects, I use these unresolved questions I carried throughout my childhood as a starting point. Constantly in search of answers, I'm looking for a way to express this through photography.

On Teaching

It’s important that a person doesn’t just learn how to take a beautiful photo, but also understands why he wants to take it. My students often say, “I want to learn how to take photos so I can put together a story,” or, “to take a beautiful picture,” or, “to speak a visual language.” These statements don’t answer the main question: why? Learning how to do it in a vacuum is meaningless. For me, photography is a way to talk about things that haunt me.

Under the title of “photographer,” people often take us to be those who know how to take a beautiful photo according to certain canons. It seems sometimes that this comes from our fathers’ generation, who were brought up on a carefully selected and approved body of literature and art from the 19th century and the realism of the 20th century. During Soviet times, people chose the classics because it didn’t brainwash you like propaganda and allowed you to simply enjoy the quality of work. That’s where we get the impression of an intelligent person who knows and loves the classics. This is also true with photography. You could look at a Cartier-Bresson, but contemporary art barely ever got to us, so any innovation is a departure from the canons and now is difficult to accept. However this will pass, and even now you notice that people are becoming more flexible in regard to photography.

On Subjectivity in Photography

Talking about news photos, we understand that there is some kind of conventional truth that we need to convey. Now there is a lot of talk about this over the situation with one of the World Press Photo winners. It’s probably an eternal debate. It’s impossible to achieve objectivity in photography, as it’s clearly always a subjective decision taken by a real person here and now: pressing the button and fixing the lighting reflected by the subject.

My students at the department of photography, having been instructed to take the most objective photo, came to the conclusion that you have to solve the problem of choosing the right moment and the composition of the shot. So, some of the students marked pressing the shutter release as dependent on some natural phenomena, such as vibrations of water in a pool. Others decided that an objective photograph is something not taken by you, but by something else, such as Google street view or CCTV cameras. One solution was choosing photos that a student exchanged via instant messenger while shopping for clothes or when she just wanted to show her friend something funny. It was an interesting thought, that we approach “objectivity” not when trying to take a photo, but using a picture as a means of communication that explains what we want to say more quickly.

On Commercial Projects

When people ask me how I manage to make money on photography, I laugh and say that I'm an anti-commercial photographer because I do everything wrong. For example, I finance all of my projects myself without looking for money for them in advance. European photographers look for money first, and I always think that there isn't any time for that and that I urgently need to implement my plans, and that's way more important. The point is that I don't have any quick jobs to make money on. But I know that there is an algorithm that you can use in order to make everyone aware of your project and that it won't only bring you fame, but also some kind of material compensation. Here, for example, the Polish photographer Rafal Milach, who looks for funding and applies for grants himself, and each new project of his is simultaneously showcased worldwide and used as material in magazines and print books. Or, the Dutch photographer Anais Lopes. Before she even finishes her project everyone already knows about it.

On Politics

I'm very skeptical towards the waves of hysteria coming from the Internet. Because of the abundance of social networks, the fragmentation of our consciousness, and the habit of reading the short and emotional, we tend not to think that there is something we don't know. We have an opinion about everything, and this opinion successfully falls within everything that correlates to it. It's tough to expand the scope, sometimes.

Is it necessary to react to events? I think that you need to do something, but maintain your distance. For example, I almost never read the news, but still I know about what's going on. I sincerely worry about other people's emotions and try to shield myself from them. I think that in my last two projects ("The Alphabet of Common Words" and "Communion" - BIF) I got this distance.

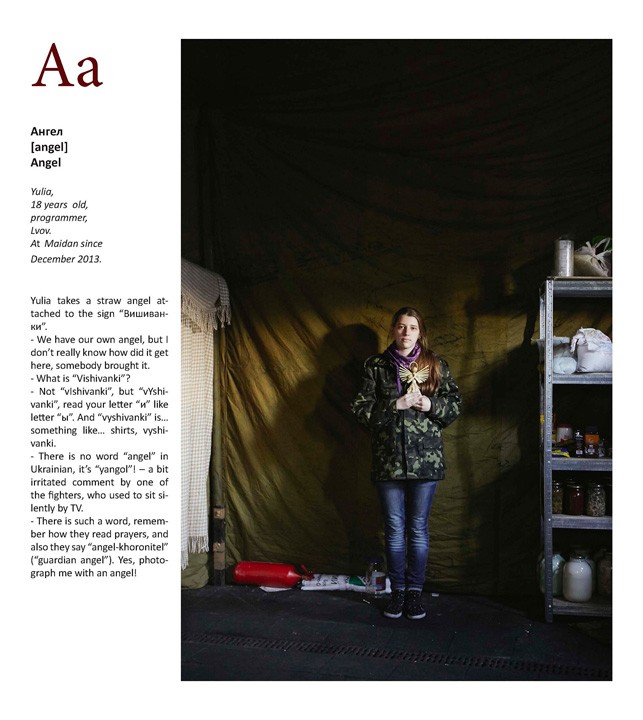

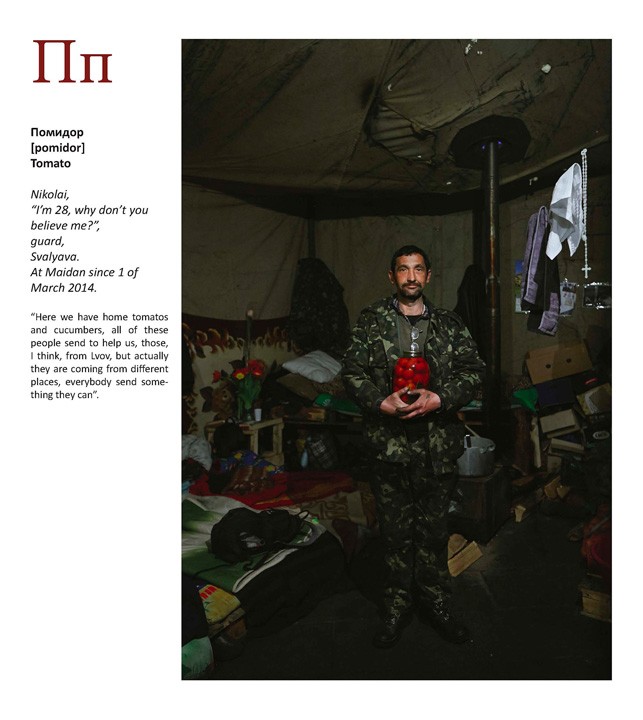

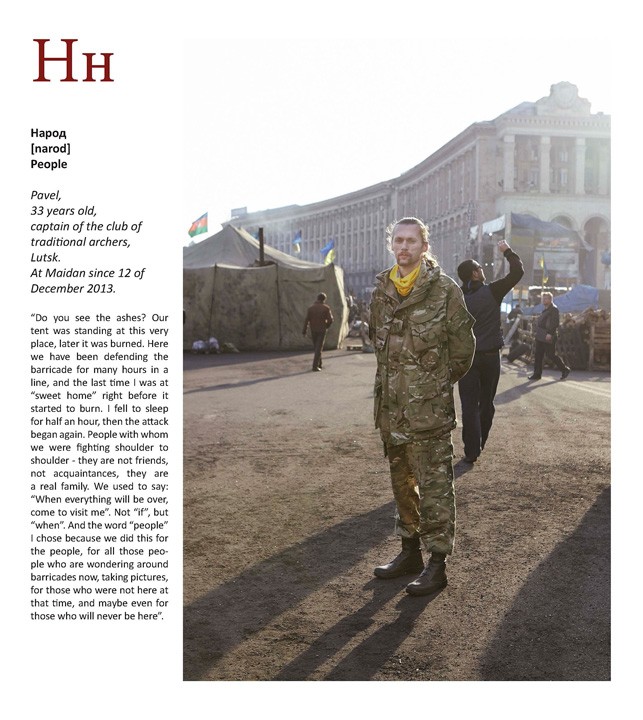

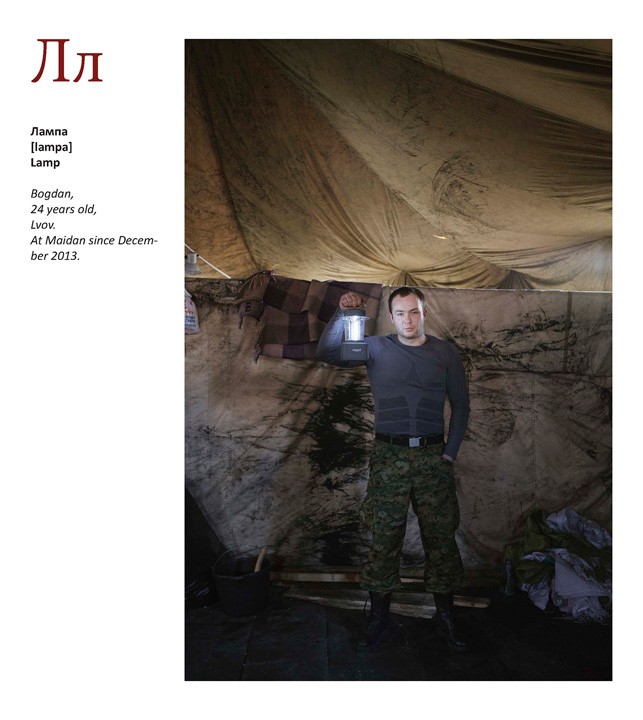

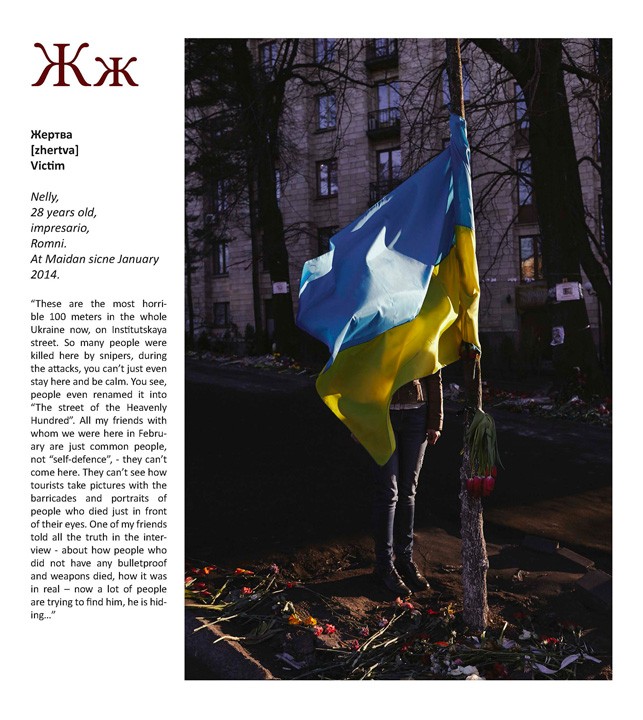

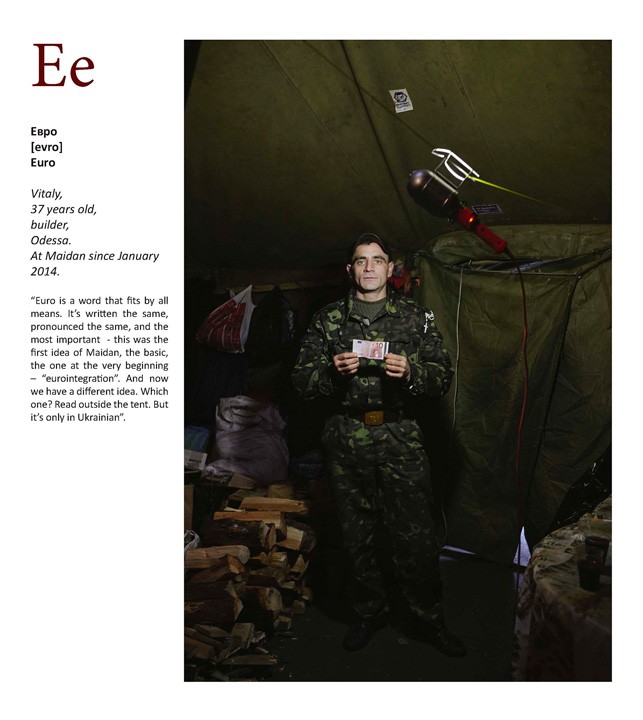

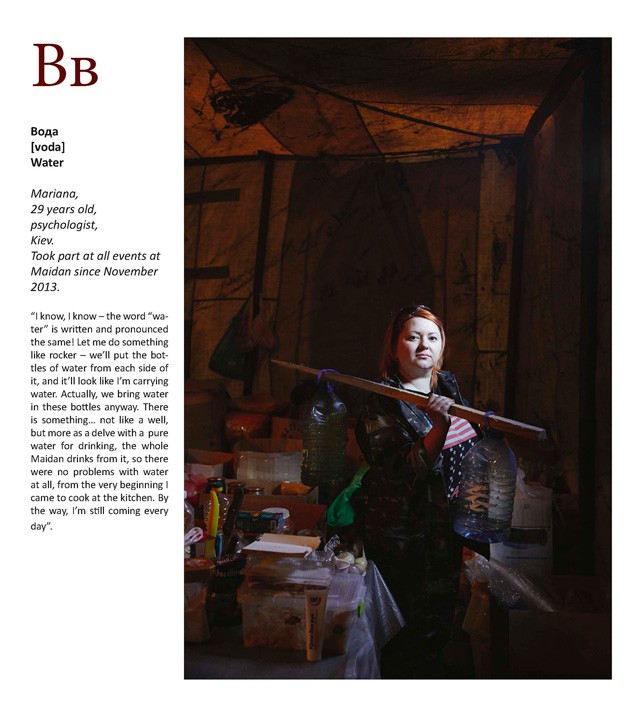

On "The Alphabet of Common Words"

I only found out about the revolution in Ukraine on March 1st, 2014. For two months before that I was at the Olympic Games and was disconnected. Going to Kiev was an absolutely impulsive decision.

When I was there, everyone on both sides said that Russians and Ukrainians don’t understand each other anymore. I started to think about what understanding is and where the base level, on which we understand each other under any circumstances, is.

That’s how I started shooting “The Alphabet of Common Words.” People themselves chose what words were interesting to them or came up with them, as illustrated. In a sense it was my attempt to get rid of the bias, subjectivity, and the imposition of meaning which is already known in advance, supposedly. I enter into cooperation with each person I shoot on camera.

At the beginning it seemed like nothing would come of this project and it would just be a game, but the first person I photographed approached this story sincerely and really wanted to understand and be understood by others. Some of the “Alphabet” characters even believed that this project would be able to stop the war.

On "Communion"

How can a person, having lived through three changes in government, figure out who he is? You are born in one country, live in another, and then suddenly find yourself in a third one. There are a huge number of monuments in Sevastopol dedicated to the war. In what way does urban space form you as an individual?

I was looking for characters among people of my generation in Sevastopol for the project. I helped volunteers there clean up garbage and met someone there that I found in VKontakte. I got messages several times asking me to leave because I am “the enemy.” People came to my site and saw the photos from Maidan without even bothering to consider what the meaning behind them is, “If you were taking photos on Maidan, you won’t understand us.”

When I was searching for those who don’t support the pro-Russian point of view, they answered me, “How can you take pictures of us? You’re from Russia!” It’s the same broken logic in a mirror image. After a few questions, people began to understand that they sounded silly and then also agreed to participate. With my characters, we spoke about what nationality is and how they understand it.

Once, I was asked whether I’d like to publish the project in a Ukrainian journal, and I thought that in Ukraine people wouldn’t take the story as kindly as in Russia, seeing the story as one only about “traitors” without being able to fully grasp it. Here, I understood that I had begun to think the same way as many of my characters. It’s dumb logic and it was important to understand myself just in time. If your projects and your work don’t change you yourself, then they’re certainly not worth seeing through.

New and best