The Silence of the Sands: Oil Mining Landscapes in Stuart Hall’s Project

Born and lives in a coal mining town in Nottinghamshire, England. He started as a commercial photographer working with Nadav Kander, Richard Avedon, publishing in glossy magazines. After becoming famous for commercial works he turned to landscape photography.

Tar Sands

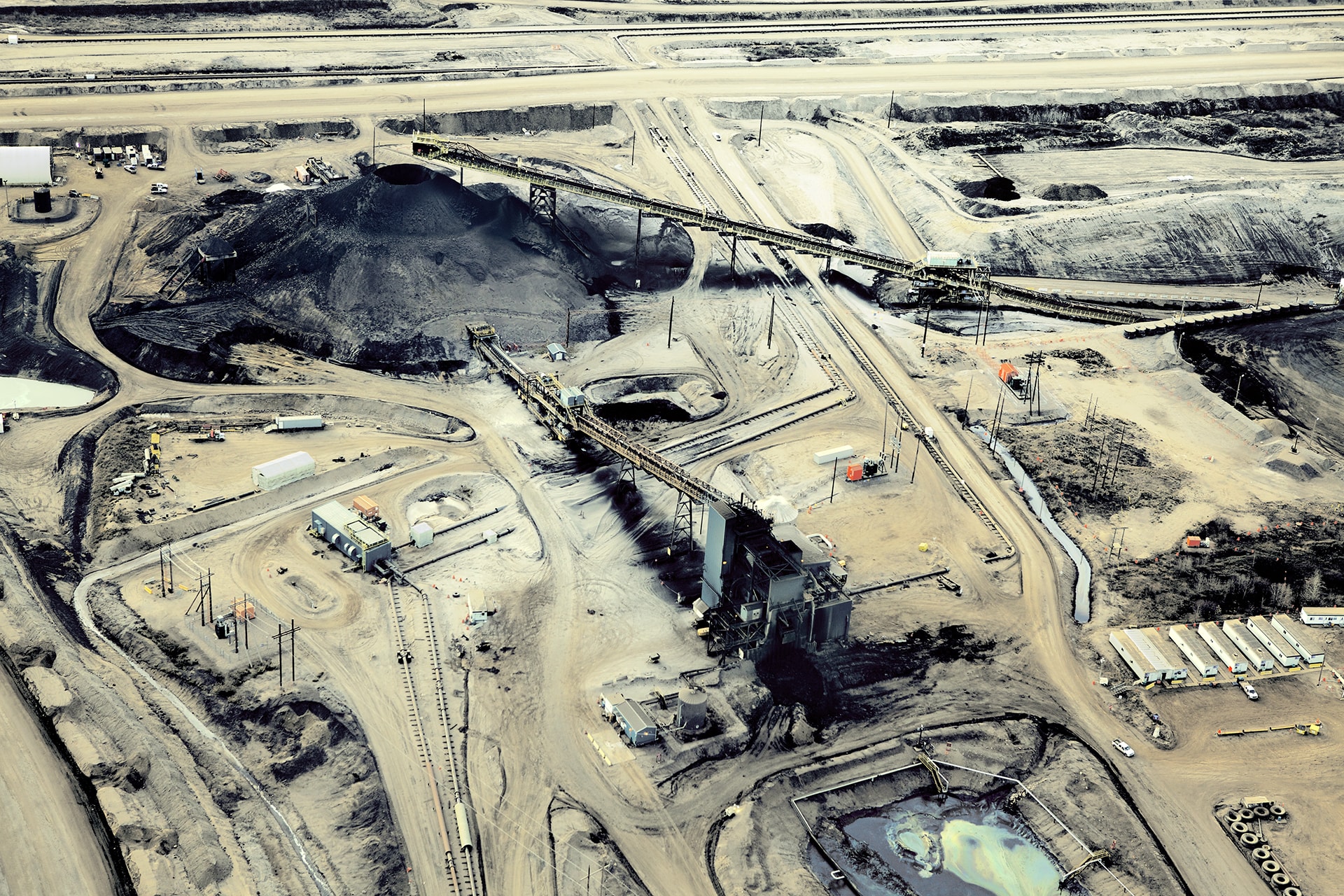

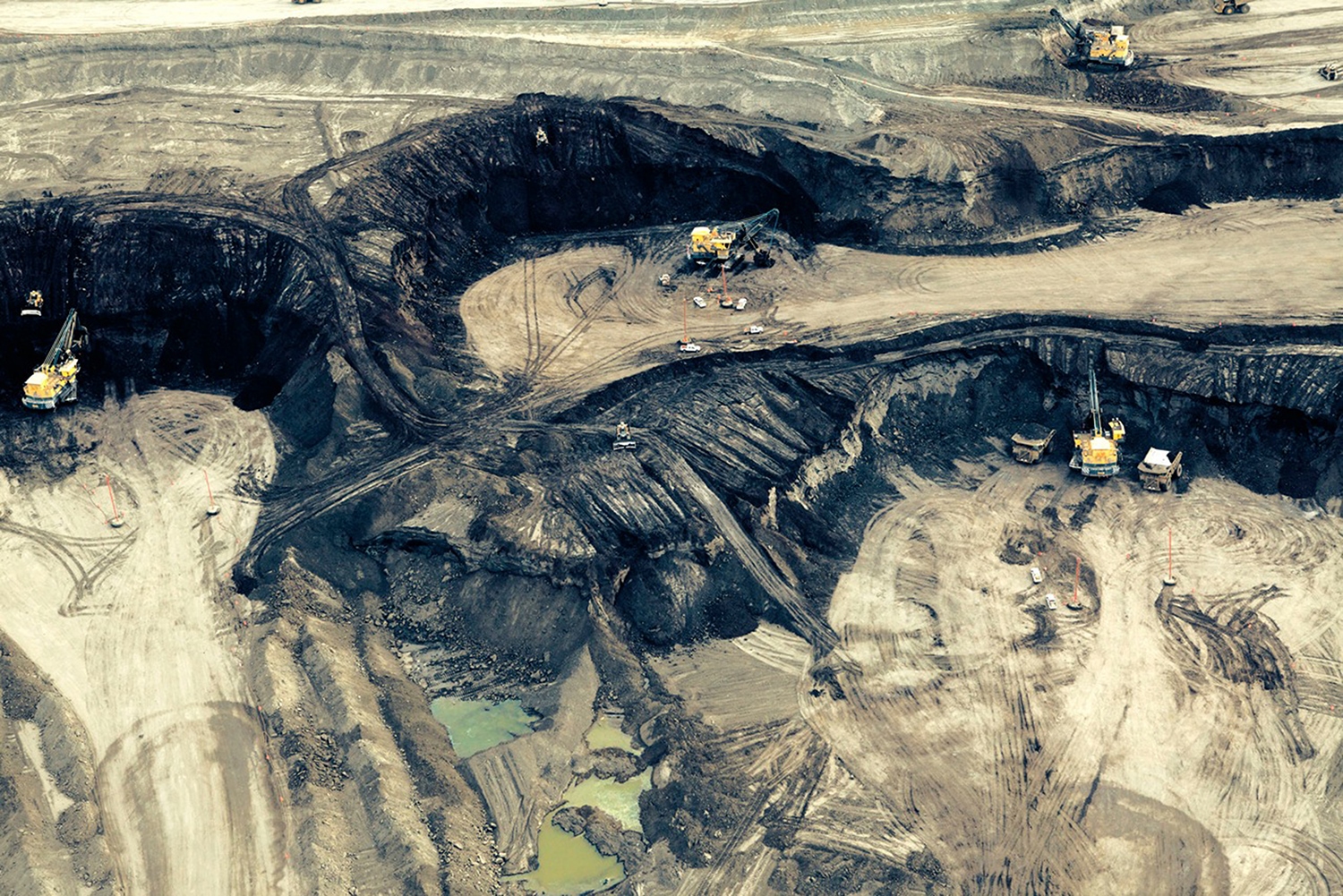

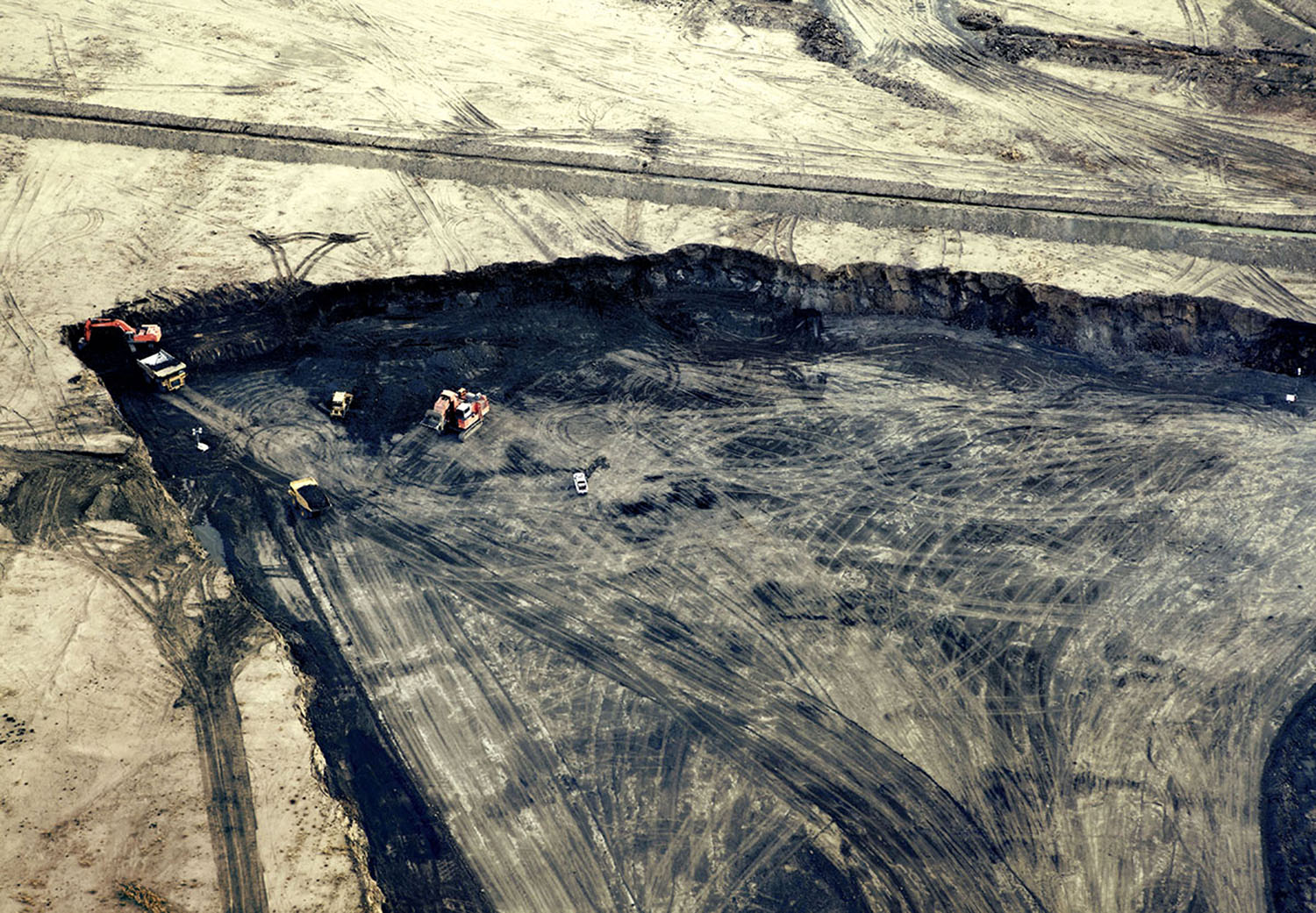

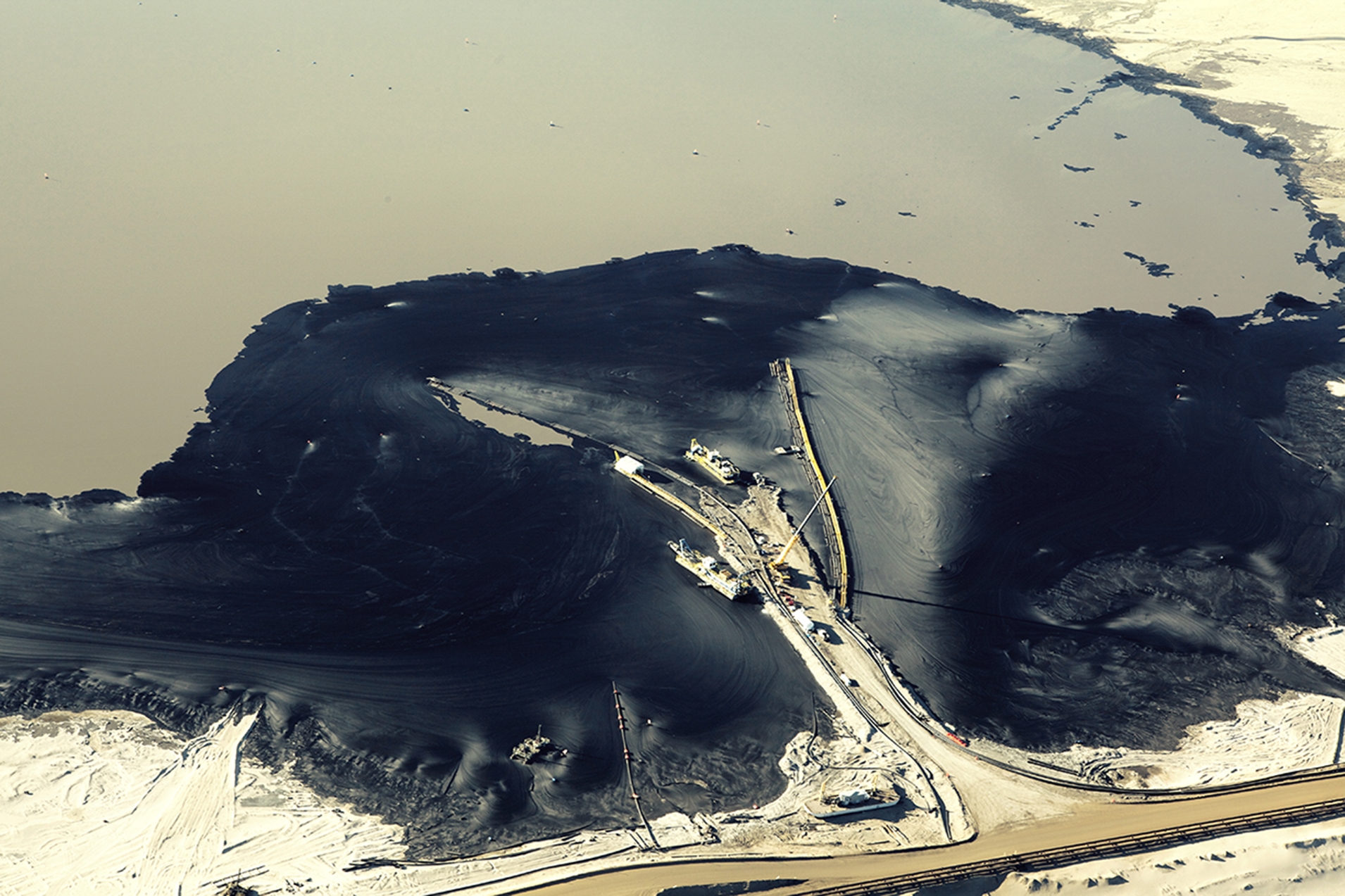

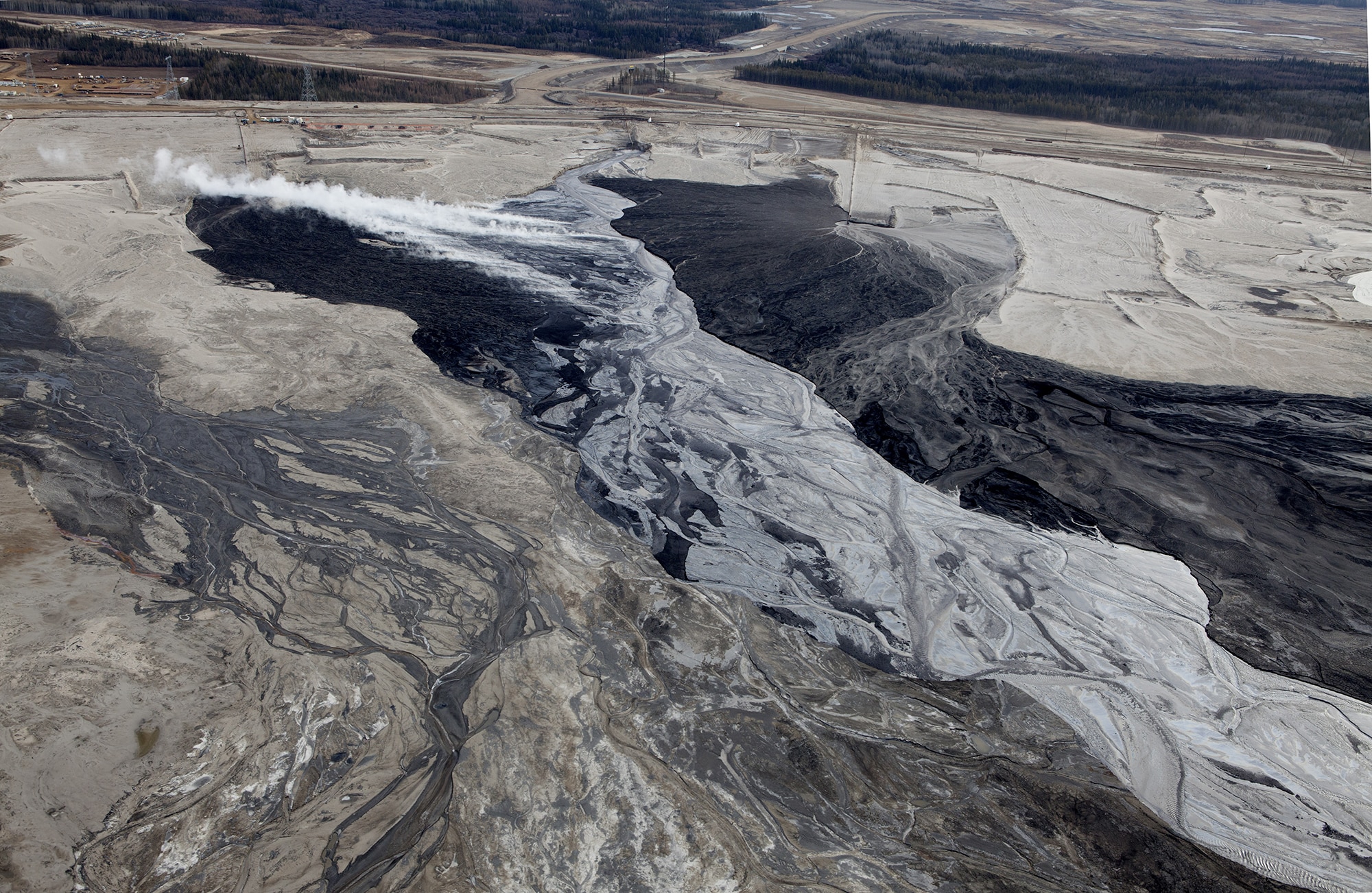

The tar sands in Canada are the 3rd largest field of oil in the world after ones in Saudi Arabia and Venezuela: the 141,000 square kilometers (a little bit more than a size of Greece) contain 170 billion barrels of oil. To produce one barrel of oil it takes two tons of tar sands and several barrels of water, which also becomes toxic afterwards. To extract petroleum from oil sands development companies use huge earth-moving trucks and excavators to dig 20-50 meters under the surface and then release steam or solvents into the bitumen underground reservoirs. Another way is open surface mining with the use of the hydraulic power shovels. Both methods are highly destructive, they leave toxic ponds, lifeless and toxic grounds, cut boreal forest and its wildlife, and release more more greenhouse gas than conventional oil production.

I started photographing tar sands in Canada in 2011. They were a chasing theme: family members living in that area, colleagues, talking about it, photos and articles you occasionally come across. It came back again and again before it finally made me come and see for myself. As it takes me a really long time to understand all my feelings about the image, I’m still setting photographs from the project, despite the last images being shot in 2014.

To be honest, I knew that my presence would be intimidating in a small town of oil workers. So I kept my head down: I rented a plane at the local airport, did the shooting, and then went back to my motel room to hide until the next day.

There are no close-ups of workers or machinery, landscape only. I’d like to go back and take photographs of the locals but that’s not that easy. Migration workers interviewed me more than an hour the first time I came to Canada. When you tell them that you are a photographer going to Alberta for the tar sands, they suggest you visit the beautiful lakes and forests. Understanding how destructive tar sands mining is they oppose all the photographers coming to Athabasca. No matter what the mining company states, one image reveals the level of destruction. Their opposition is understandable.

I’m not a green campaigner, I’m an artist. During my 25 years doing photography, I’ve been working on every continent all over the world and I have seen amazing landscapes. Tar sands mining is destructive, there is no denying, but I think I’ve made this destruction look quite beautiful. They are very quiet. As all my images are in general.

We need oil and tar sands as a part of the process of how we get it. And that is okay to show that. I find all this very fascinating and photogenic to photograph. Cities themselves are the results of man-made destruction, but we photograph them a lot. The sun rising over the mountains doesn’t interest me anymore.

I could be one of the tar sands miners so I’m definitely not making any statement. The other day I caught a plane back to Toronto at the end of the week. It was full of miners going back to their families, loving, caring, and having to make money for their kids.

The vastness of the mining project is the main thing that still leads me. The earth-moving truck is like a caterpillar eating through the leaf. It is so tiny but the scar is so huge. That says a lot about how we change things: destruction is a part of a big learning process.