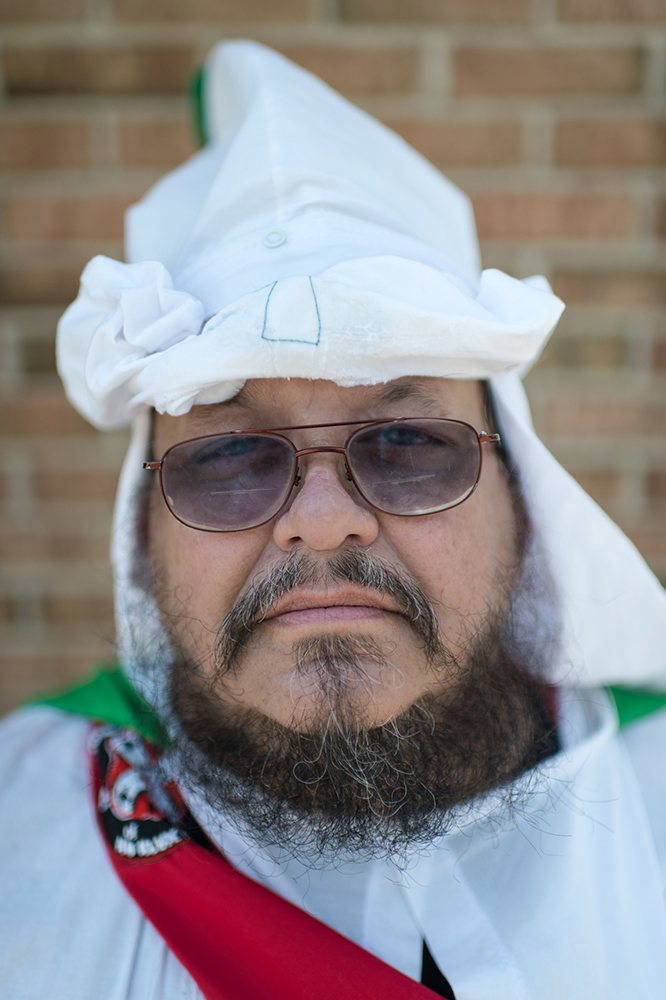

White Guard: Modern Followers of KKK in Anthony Karen’s Project

Photographer from New York. Was a marine and has worked in the industry of personal protective equipment for many years. Became interested in photography in Haiti, where he captured voodoo rituals. Works on several large documentary projects on skinheads, baptists, and the KKK. The latter resulted in two books and exhibitions in Bulgaria and Italy, and was also shown during a night screening at the Visa pour l'Image festival in Perpignan. Worked for NPR radio, Life, Time, Mother Jones, The Washington Post, and Slate. Received two MIN Editorial Awards in 2011. Received a George A. Robinson IV Foundation grant the same year and won Cliff Edom’s New America Award for The Best Photojournalist.

— I have a keen interest in religious ideology and marginalized subject matter. In my opinion, these types of stories are often documented in a superficial and sensationalist manner, they also can be the most challenging.

I knew that the Klan had been photographed many times before, including by well-known photojournalists, but I felt the majority of images hinged on sensationalism and focused primarily on the obvious — the robes and the cross lighting ceremony. It became my objective to capture the most interesting and basic element, one that would be the most challenging and difficult for other photographers to follow — an intimate look into these various white separatist organizations. Not to mention, I was honestly curious to see things for myself.

A general constitutional of qualifications for Klan membership is as follows: “Applicant must be a white person of non-Jewish ancestry, a non-user of drugs with no misdemeanor or felony convictions and must … be of sound mind, good character, free of any homosexual activities, have a commendable reputation and a respectable vocation, be a believer in the tenants (sic) of the Christian religion, and one whose allegiance, loyalty and devotion to the the Ku Klux Klan in all things is unquestionable.”

If a candidate meets those requirements, he/she would submit an application, followed by a background investigation, probationary period and lastly the “Naturalization” ritual. At the completion of the Naturalization, the probate swears an oath to the Klan and is knighted.

It’s not bunch of “rednecks” walking around in Klan robes all day talking about lynching black people. Aside from an individual wearing a racially themed shirt or having a visible tattoo(s), you’d never know someone was in the Klan unless they decided to share that with you. Granted, you may come across the typical stereotype, but it’s not as common as people imagine.

Most Klan gatherings are nothing more than a large cookout (including the obvious racist overtones) with the culmination being the cross lighting ceremony. According to Klan ideology, the meaning of the cross lighting is to “signify the light of Christ” and to “bring light to a world in darkness” (misinformation).

The Klan holds the cross lighting in great reverence and claim that the hate motivated cross lightings in the past were the result of rogue members or offshoot Klan groups in an effort to intimidate and terrorize — the Silver Dollar Group and Cottonmouth Moccasin Gang were two such offshoots and were responsible for many violent crimes during the Civil Rights Era.

It’s difficult to say for certain how many members the Klan has. The Alabama-based SPLC (Southern Poverty Law Center) estimates that the Klan has about 190 chapters nationally with no more than 6,000 members total, which would be a mere shadow of its estimated 2 million to 5 million members in the 1920s.

In regards to the Klan and “community” — The Ku Klux Klan officially disbanded in 1944 when the federal government demanded payment of more than $600,000 in back taxes. As a result, the name “Ku Klux Klan” became public domain. The organization lost all claim to the original copyrights… this was the last time the Klan was unified as an organization. Shortly following, new independent groups began to appear throughout the country. Even today, some groups may have as few as 3 members; others may be in the hundreds across multiple states to being completely off the grid.

Whenever you’re granted access into a person’s intimate space, you’re establishing a relationship of sorts. Yes, I have made friends over the years. That doesn’t suggest I’ve become complacent with my situation to the point of exploitation, nor does it mean I’m selectively disregarding certain moments to depict something that is not. I do admit I try to offer a balanced perspective as to my experiences within marginalized originations, such as the Ku Klux Klan for example, but to consciously distance myself will in effect (or could) create biases.

Understandably, some were guarded and wanted nothing to do with me at first. As a photographer, you can’t expect people to give of themselves unless you are open yourself. Once your subject feels that you respect them as a person, they tend to forget about the camera altogether and the intimacy will occur naturally. It’s important to document people after this point, opposed to when they’re on guard… otherwise your images (and experience) will only scratch the surface.

My first documentation of the Ku Klux Klan was in 2005. I attended various gatherings, ceremonies, demonstrations and visited individuals in their homes over an 11-year span. Many of my projects don’t necessarily have a definitive ‘end’ per se, so if I’m able to document more of a particular story I will try my best to keep things current… the Klan is one such project.

New and best