One Day I Will Return Home Forever: Ukraine of the 90s in the Photos of Catherine Turchan

Photographer. Her works are represented in museums and galleries worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She lives and works in the United States and spends a lot of time in Ukraine with her family.

— My grandfather taught me how to see and to look at things. He was born and raised in a small village called Kobylovoloky in Ternopil region, and later joined the Sichovi Striltsi and fought against the Bolsheviks. When he returned home, his father was very worried that he and his brothers would be imprisoned or worse, so my grandfather decided to leave for America.

He settled in New Jersey, where he set up a small farm with sheep and chickens – just like at home. Soon his sister came to him, and I spent a lot of time with them. I think they influenced me even more than my parents, who were always busy. I would come to my grandfather, sit with him in the kitchen, and learn to draw. He was very talented and taught me to look closely at everything around me. I drew Easter eggs, and he drew portraits of his family. He didn’t have money for paper and drew on the margins of the Ukrainian-American newspaper “Svoboda.” There is no better metaphor for this.

My grandfather didn’t have money for paper, so he drew on the margins of the Ukrainian-American newspaper “Svoboda”.

He often told me stories about his family: his father who was a school director and organized a theater group there, his aunt who once painted a shroud for the local church. Sometimes he showed me his scar on his ribs, which was left by a bullet when he was a Ukrainian insurgent. I traced my fingers along his scar and drew patterns on it. And sometimes we would sit in his car and drive to the city to observe people and make quick sketches. He said we were collecting people. I think that as I grew up, I started doing just that.

My grandfather, my mother’s father, was a patriot, but he couldn’t return to Ukraine and eventually didn’t want to. The idea of going back home terrified my father, who managed to escape after World War II. But two years after my grandfather’s death, I realized that I wanted to go. It was then that my parents were diagnosed with early onset dementia. As an artist, I had a choice: to photograph their slow fading away or to return to the place where they came from and where, perhaps, they lost something very valuable. I received a scholarship from Yale University and set off on a journey.

I decided not to tell my Ukrainian relatives that I was coming so as not to burden them with my presence. I didn’t know how they would receive me. Thanks to the Ukrainian-American organization, I was able to get a theater visa, which was then issued to dancers, musicians, and other artists. It’s worth mentioning that my relatives were quite well-known musicians in Lviv and Kyiv. My uncle was the conductor of the “Trembita” orchestra in Lviv. My cousin Romana was a bandura player, and cousin Yuriy was a jazz musician and member of the National Opera of Ukraine. So somehow, through their music circles, they found out about my arrival. They unexpectedly came to my hotel and took me home. It was an extremely emotional moment.

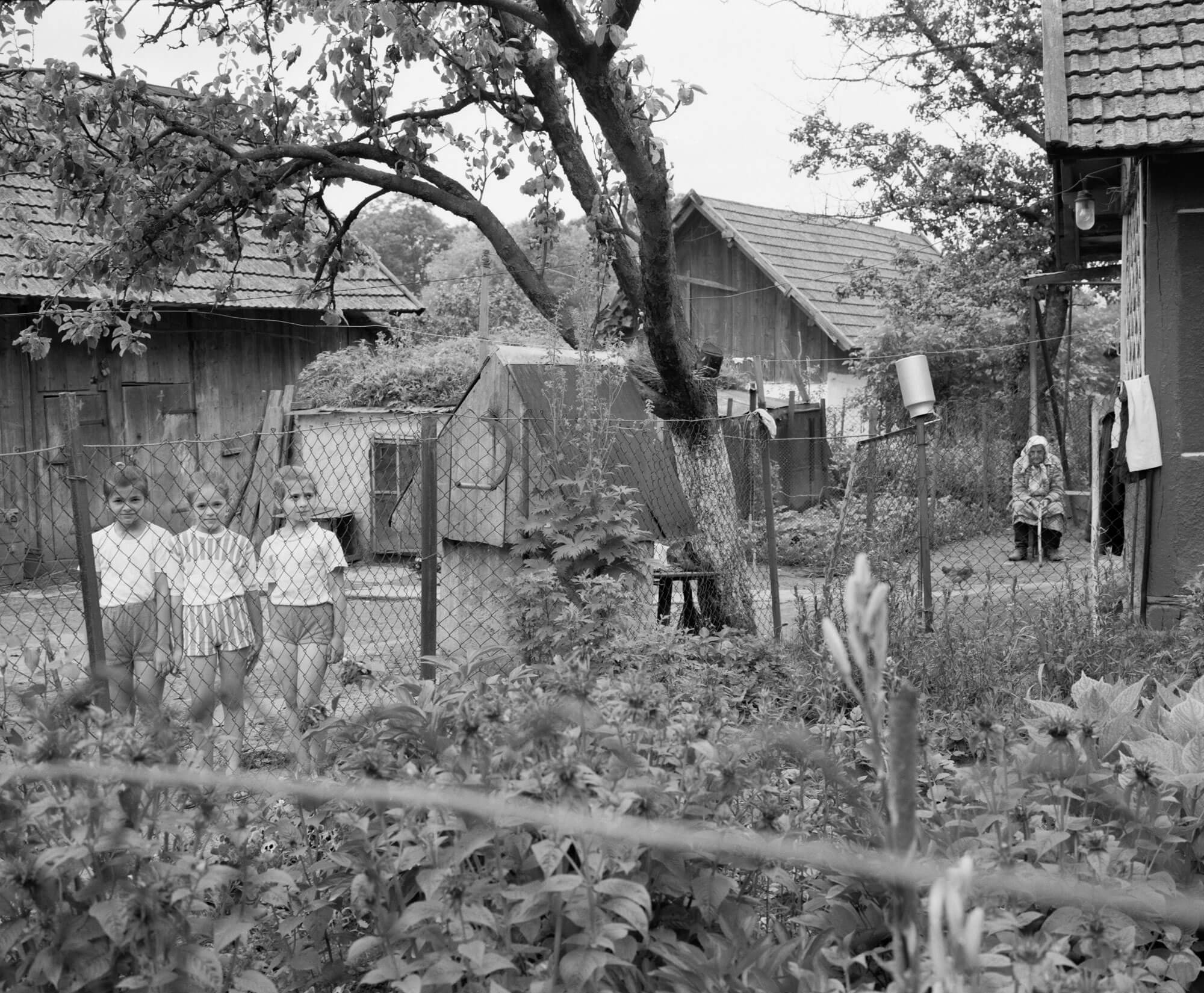

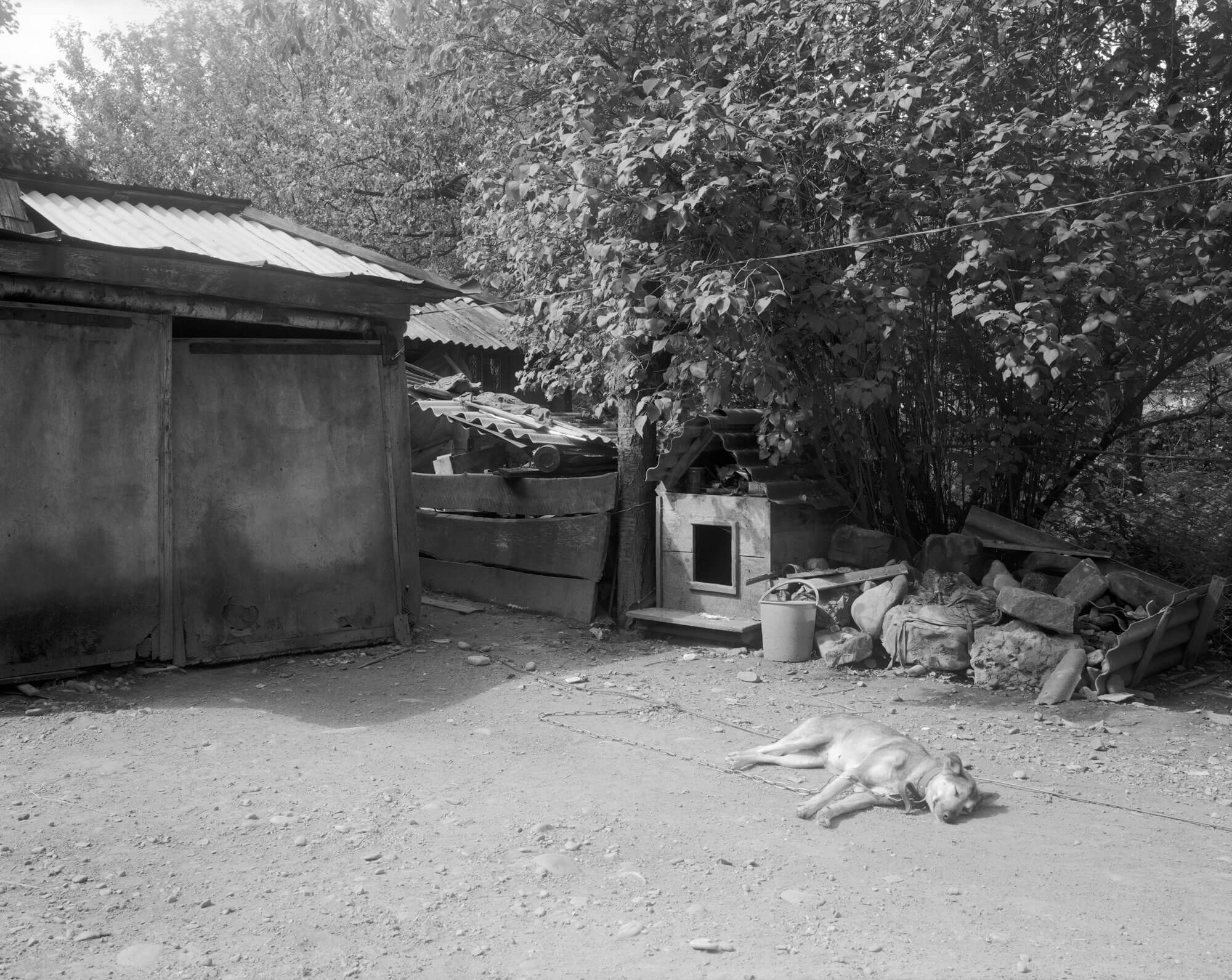

My first trip to Ukraine was during a very difficult time. It was May 1991, four months before the collapse of the Soviet Union. Of course, I was happy to be reunited with my family again, but I was shocked and depressed by what I saw around me. People were standing in lines for sugar and bread, coupons were used instead of money, and it was hard. It seemed like Ukraine was frozen in time. One day, we went to Slavske in the Carpathian Mountains, and it felt like I had stepped into my grandfather’s stories – nothing had changed. The big cities were better, but not by much.

However, I was young and happy, and not afraid to walk the Soviet streets with my huge camera. Except for one day, when Romana and I went to Kyiv. From early morning, “Swan Lake” was being broadcast on TV. We turned on the radio – “Swan Lake” again. So I said, “Roma, I’m frightened.” So we went to the street to ask what people knew. No one knew that at that time there was a coup d’état, but we felt the fear in the air. At that time, I couldn’t just call home to America. So I went to the post office and requested a call to the States, which took three days. During that time, I was afraid that tanks would come to the city. Finally, I was able to change my tickets and return to America.

Since then, I have been coming to Ukraine almost every year and staying with my relatives. We have become very close. I was impressed by how quickly the country began to develop after the collapse of the Soviet Union. By 1994, you could see how refined Ukrainians had become. They quickly embraced the European culture that they always aspired to. Sometimes my cousins would tell me something about fashion or music, and I didn’t understand what they were talking about. They had surpassed me so quickly – I didn’t even have time to catch up and became the clumsy relative from America.

After 1994, one could see how sophisticated Ukrainians had become. They quickly embraced the European culture they had always aspired to.

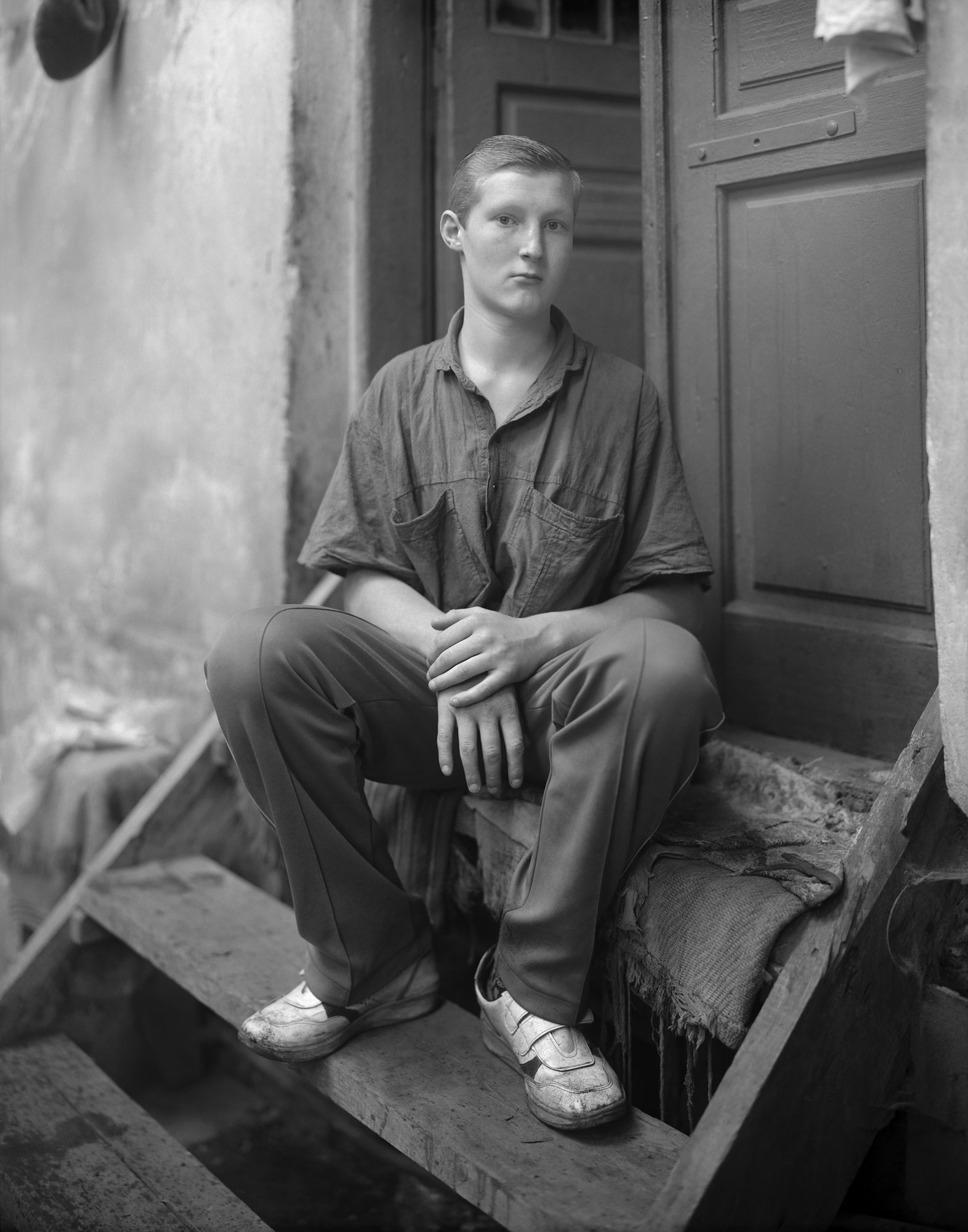

I always stayed for a long time, a month or more. I work with a large format and a big camera, so I need a lot of time to take a photo. It’s not at all like photojournalism, where everything happens quickly. Here, conversation, understanding, and acceptance are required. Sometimes it seems to me that the process of shooting becomes like meditation. Of course, I often photographed my family, but I was also interested in strangers, especially women. Perhaps it’s a stereotype, but I feel that women hold families together, and I wanted to see how their lives were changing during such a difficult time for the country. I looked at them and imagined what my life would be like if my grandfather hadn’t emigrated to America. I doubt I would have become a photographer. It would have been too expensive of a hobby here.

I imagined what my life would be like if my grandfather had not emigrated to America. I doubt that I would have become a photographer.

Among my photos, there are many images of nuns. Partially because my mother once wanted to become a nun, but also because I was interested in their life choices. I think they joined the church not only because of their spiritual calling, but also to have a more stable and secure life amidst the chaos. I also often photographed children. In the 1990s, they were sent to camps every summer to recover after the Chernobyl disaster. Their childhood was not easy, but they still looked happy and carefree.

In the 2000s, I had the opportunity to visit Crimea, travel along the southern coast, visit Odessa and the eastern part of Ukraine. My last trip to Ukraine took place just before the COVID-19 pandemic. And then a full-scale war began. When this happened, I did not think about my photos. My thoughts were with my loved ones, I cried every day. Only later, I looked through old files and realized that these photographs should have been posted on social media. I wanted them to somehow balance the images of violence and pain that filled the photos from Ukraine. But I doubted whether to publish them. After all, photojournalists had taken so many important photos – more important than my work at the time. Eventually, I decided that we all should speak about Ukraine in any way available to us.

So my photos got a second life. I compiled them into a book called “From Where They Come” and reissued it in 2023. In the preface, there is a story written by Sofiya Andrukhovych. Actually, I had to persuade her to write the text, but it was worth it. She has a very deep understanding of the history of Ukraine in all its complexity and imperfection. I wanted my photos to also reflect the history as it is – complicated, but gentle, calm and full of love.

I wanted my photos to reflect a history that is complex, yet tender, peaceful, and filled with love.

Currently, I keep in constant contact with my family. I invited them all to come to America when the full-scale invasion started. Yuri refused – he returned to work at the opera. And Roman emigrated to the States many years ago. She passed away from cancer before the start of the war, and we brought her body back to Lviv and buried her at the Lychakiv Cemetery. When my time comes, my ashes will also be buried there, next to her and our family. So one day, I will return home forever.

The book by Catherine Turczan can be purchased at the link.

New and best