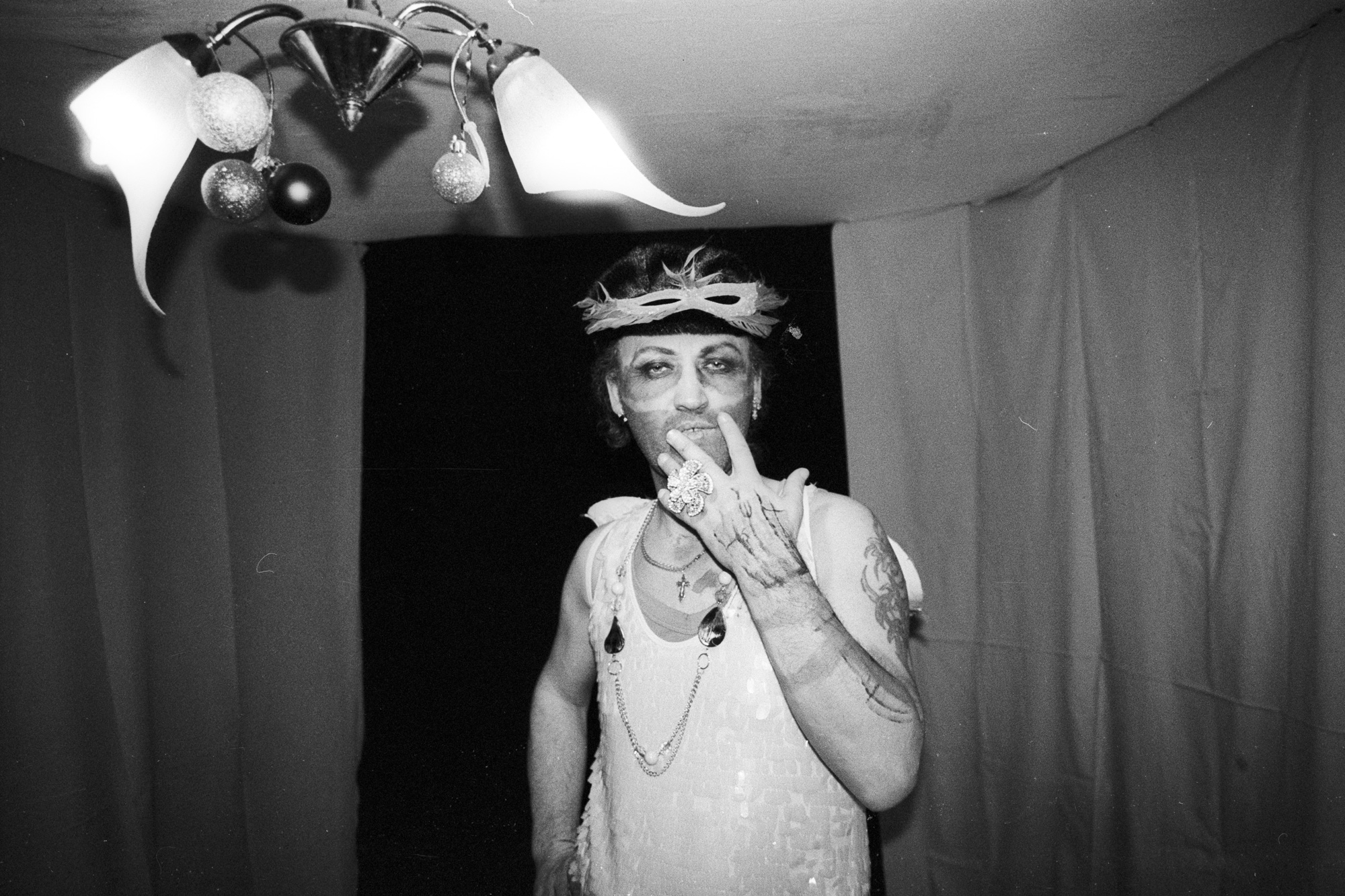

Mikhail Koptev: “Some Were Too Ashamed to Sit in the Audience, So They Watched My Show from Behind the Curtains”

Photo: Andrey Boyko, especially for Bird in Flight

In 1993, Mikhail Koptev organized a theater of provocative fashion Orchid in his native Luhansk. It had nothing to do with either theater or fashion. Young women with heavy makeup dressed in transparent clothes with cleavage ending somewhere at their genitals, stupefied people in the audience, dressed in sheepskin coats holding their beers — photo reports from Koptev’s shows were making the social networks that were just gaining popularity explode.

One of the curators for Visual Culture Research Center saw contemporary art in Koptev’s work, and invited his theater for the 2015 Kyiv Biennial — Kyiv School. Thanks to this invitation, Koptev got out of the village near Luhansk where he was living and waiting for the war to end, and gathered the new cast of Orchid. And a year later, at the invitation of the Austrian curators Georg Schöllhammer and Hedwig Saxenhuber, the Orchid performed in the WUK cultural center in Vienna.

Koptev told art critic Anna Tsyba how the shoe factory worker had the idea of becoming a fashion designer, where he finds models for his shows, and why he took up performing again after a long break.

How do you define the work that you do?

I am a multilayered pie of contradictions. I can’t be described in one word. Am I fashion designer or a stripper? I work between genres.

In my understanding, what you do is contemporary art…

Yes, I am an artist. My canvas and paints are models and people in the audience, hair brushes and makeup, costumes and posters.

Fashion business is a joke to me: fashion designers make up explanations for their new clothing, all serious and pompous, but in fact keep showing the same thing for 20 years. I want to tell them to drink some moonshine and say something funny for the cameras, and not make fools of themselves, giving serious comments with clever faces.

At some point, you renamed Orchid from theater to Provocative Fashion Circus. Why?

When my theater became popular, new fashion theaters started popping up in Luhansk every week. All of them were similarly pathetic and modest: no erotics and bad music — just the hits that you can hear on the radio. I realized that I need to distinguish myself contra those theaters. Out of spite, I renamed Orchid into a Circus and made a corresponding logo.

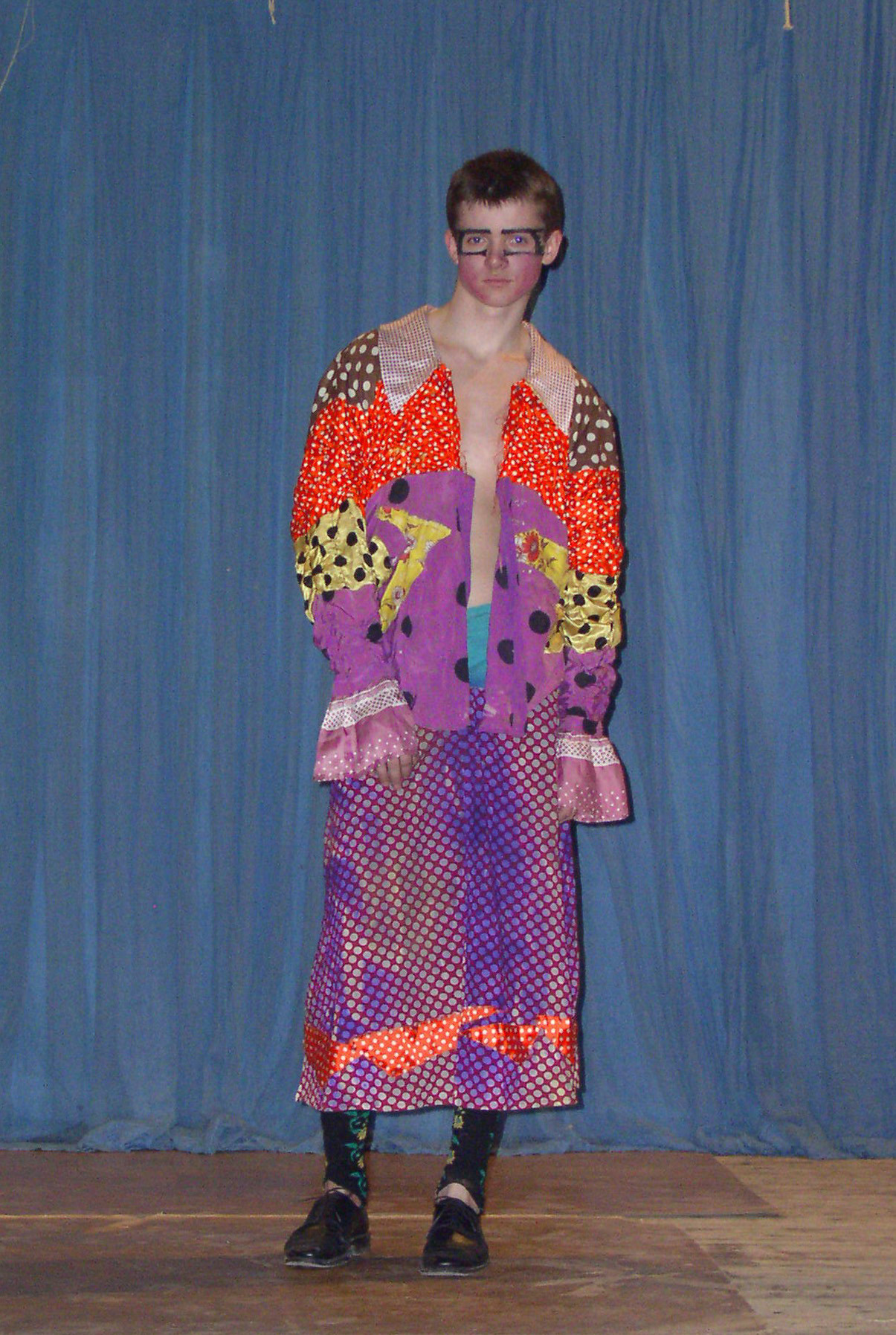

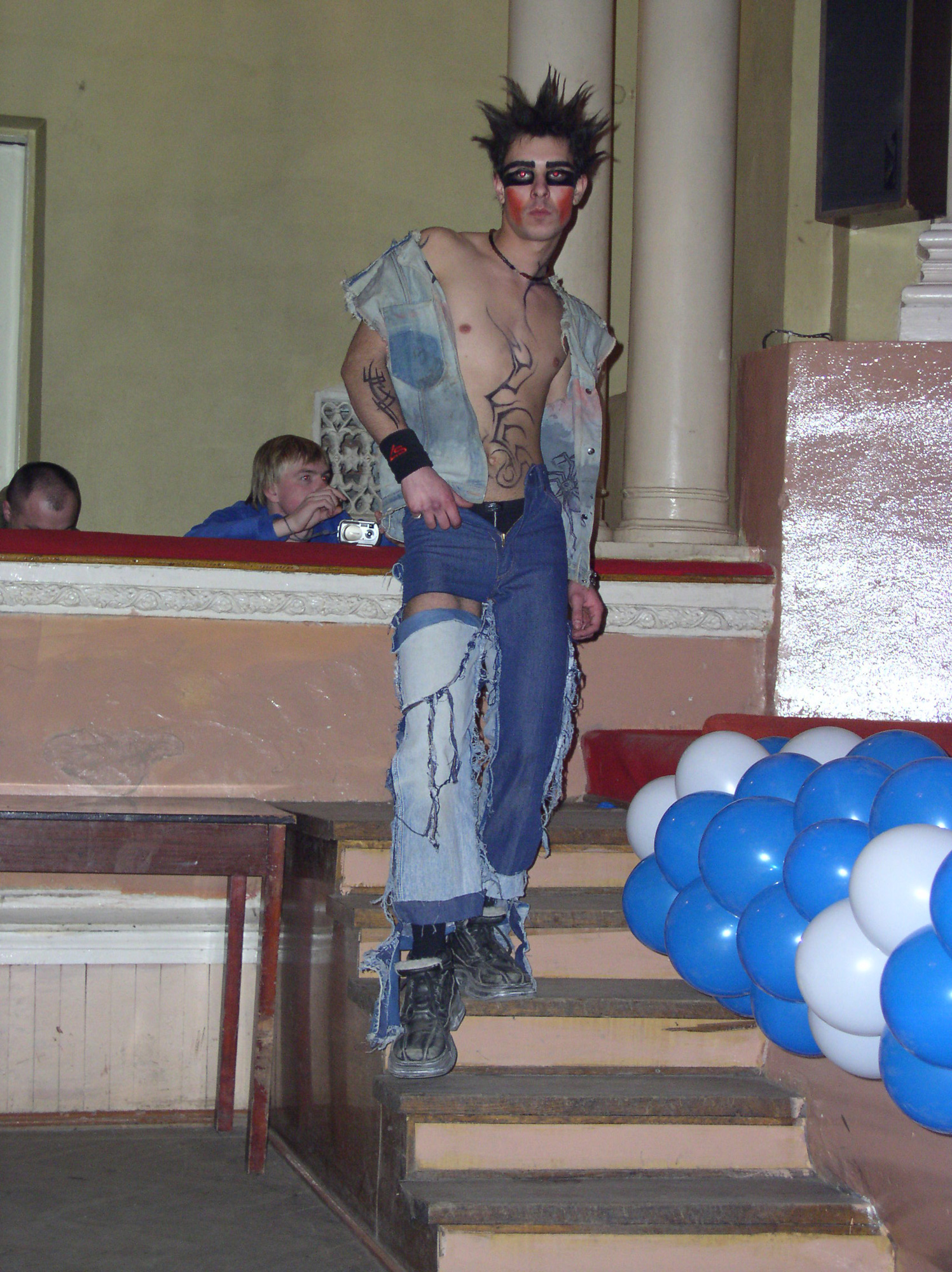

Image from Mikhal Koptev’s archive

How did Orchid come to life?

As a young man, I was working at a shoe factory in Luhansk, and at some point I heard about a fashion theater. You could pay to go to study there, which I did. We studied defile, history and theory of costume, ballroom dancing, manicure and pedicure techniques. We also worked as models, showing the clothes made by the theater founder — some terrible geometrical nonsense made from coarse cotton. We were children, we wanted to model, to shine on the podium, dress up, wear crazy makeup, and our hair crazy.

Later, I became an executive director of this theater. I was paid a salary to cast models and work with them, organized shows. With time, I got bored with that place. I decided that I would be showing something different and left, and many models tagged along. I created my own theater, the Orchid.

In December 1993, we had our first show — in the house of culture in Luhansk. I didn’t have any money at the time, so I asked models to bring their clothes that we could either remake into something else, or just show as it was. I cut some blouses and slips, added cleavage, made skirts shorter, so that everything would be flashing. My style was showing back then — working on those old clothes, I was turning them into something worthy.

The show of Provocative Fashion Circus Orchid. Luhansk, 2009. Photo from Mikhail Koptev’s archive.

How did you get interested in fashion and working in this industry?

I guess, from fashion magazines that you could already buy back then. I gave my entire salary to get Vogue and Madame Figaro. People at the shoe factory thought I was an idiot. But these magazines had real beauty in them. I looked at advertising attentively, marveling at how people in the photo were sitting, how beautiful they all were, the surroundings, the mise-en-scenes. I looked at all that and thought how rich it all was, and how I wanted to be a part of that world.

My entire education is fashion magazines and shoemaking vocational school. I didn’t want the fashion that I saw in the streets. I was fed up with it. Everybody wearing the same jeans, mass market clothes. And I would always make original clothes for myself, traded things in second-hand shops, talked people into giving me things, added sequins that were just impossible to buy. I have a thing for sequins since those times, because I lacked them so badly when I was little.

It is hard to imagine a better time for your theater to appear that the 1990s, when after the collapse of the Soviet Union people were striving for liberation and freedom. Today’s society is much more conservative — both in Ukraine, and in Russia, and in the US.

In the Soviet Times, you couldn’t live without looking at anyone. You had to have a job, to correspond to all those requirements. Freedom is more important for me. Freedom is tastier than bread and drunker than wine.

And in the 1990s, the times were special: impunity, mismanagement, and hungry mouths everywhere. People who didn’t have cable television were buying tickets to my shows like hot cakes. Corruption flourished, and director of the house of culture made the offer herself that I make unaccounted payments to her for renting the premises. I started making shows that were commercially successful and raising my ticket prices, and she wanted to work with me, because she knew that the audience hall will always be full.

Did you start undressing models because you realize that was what people wanted? Are you now consciously overusing it?

I felt that. But most importantly, I realizes that erotics was my thing. I understood that it is expensive to dress a model in something exclusive head to toe: so that she would have a hat, shoes, accessories, and a dress. When I read that Yves Saint Laurent’s collection cost a million dollars ten years ago, I think that I could have done it better for $100,000. Colors, combinations, and silhouettes, I can do it all. But I can’t invest so much money in my shows, I just don’t have it. I am used to cheap and angry decisions.

I realized that it was easier for me to undress the models, not dress them. And because I don’t have image concerns, I can allow myself to implement everything that I feel like doing. If I want naked models — well, they will be naked then. You have a talk with a model, pour her a shot — and she undresses, what other choice she has.

I sometimes have completely dressed models, too. I try to be very meticulous in what I do: I carefully select models, and I create exclusive things.

Photo: Andrey Boyko, especially for Bird in Flight

I saw your show in Vienna and I noticed that in process you poured vodka not only to models, but also to people in the audience. Do you always do this to make people feel at ease? And does the public always have the same reaction to your shows?

Vodka helps everyone relax. Of course, modern public, European public is more tolerant. There used to be the times when people screamed during my shows, tried to touch the models, handed them cans of beer. And I used to take a bottle of vodka and pour over them, like priests pour holy water.

My first shows in Luhansk when the tickets were cheaper were mostly visited by young people. With time, as they became more popular, and prices started rising, the audience also changed — CEOs and MPs, various heads of organizations started coming. Some of them were too ashamed to sit in the audience, so they watched the show hiding behind the curtains. There were regulars who knew which aisle seats to get to see and photograph everything.

The show of Provocative Fashion Circus Orchid. Luhansk, 2009. Photo from Mikhail Koptev’s archive.

How often did you do new shows? Was the income from selling tickets enough for Orchid’s participants to make a living?

We held new shows in Luhansk twice a year — in autumn and in spring. Between them, we toured around the region, performed in nightclubs in Kyiv, Poltava, Odesa, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. It was enough to make a living, but only for me. I paid very little to the models, but they were interested in touring around other cities — of course, I paid for their tickets and accomodation. And I could make a living for myself, and until my daughter turned 18, I always could support her. Now, my daughter Ania turned 10. In 20 years, it only probably happened once or twice that I had to get employed elsewhere.

And it lasted until the LNR (unrecognized Luhansk People’s Republic) appeared? Tell us, what changed?

The war started — electricity was cut off, water stopped running, trains stopped, people left wherever they could. Windows in the Luhansk house of culture were shattered with blast waves and it was closed. Everything either became expensive or disappeared. It became impossible to buy even cat food. I had no more models, no venue, and no audience for my shows.

When a shell hit my house in Luhansk, I decided to escape to the village, hoping that there would be less shelling there. I bought a house from my friends 20 kilometers away from the city. I spent a year there: used water from a well, had farm animals, went fishing. I went up to Luhansk only once, after I heard more rumours about the entire city being shelled to ashed and everybody dying. The buses didn’t run, so I had to hitchhike. An LNR guy in uniform picked me up. He looked at me closely the entire time, and I got scared. It turned out though that he recognized me and just wanted to take a picture.

The rumors were wrong — my mom still lives in Luhansk together with my brothers and sisters. She is 80 already, and sometimes I think that if the war doesn’t end, I won’t be able to make it to my mom’s funeral. On the other hand, it’s not that important: it doesn’t make sense to cry over a dead body — you should love a person while they are alive.

I may go to Luhansk some day to visit relatives, but right now I am probably an outlaw there. I gave interviews here and abroad, and spoke about the things that I saw in LNR, including Russian soldiers, and I saw many of them there.

Did you have to face a lot of aggression because of your sometimes very extravagant appearance and behavior? Where did you experience more of it — in Ukrainian Luhansk, in LNR, or in Kyiv?

I didn’t really have an opportunity to observe LNR in the village, so I didn’t experience a lot of their ways. In Luhansk I was often attacked in the streets with homophobic slurs by regular guys and chavs. But I always fought and protected myself, and usually someone would pull us apart. I didn’t have to fight in the streets in Kyiv yet, because with age I took to dressing neutrally.

How about during your shows?

During the shows, I always had guards. I hired them for the atmosphere and to prevent a drunk audience from making too much trouble. But I never felt any danger, on the contrary — after the shows, my hands were full with notes from men and women with offers and requests to meet, go to the sauna with someone.

How did you get to Kyiv and what’s it like here for you?

With time, living in the village became unbearable, too. I lived in Mykolayivka, a hundred meters away from Siverskyi Donets river, and on the other bank of the river was Ukrainian government-controlled Stanytsia Luhanska. There was shooting back and forth all the time. The LNR guys were shooting at me, so they I would swim in the river — they may have thought I was a saboteur. They did dynamite fishing in the river, not thinking how bad it is for the ecosystem. I kept thinking: “God, when will all of this end?”, but it didn’t. And it probably won’t ever — if Russia clung to this territory, it will just become another Transnistria.

And then, Lesia Kulchytska, curator from the Visual Culture Research Center, invited me to the Kyiv Biennial. I told her that I had neither costumes nor models. But she replied: “Come, we’ll find everything you need here and make new ones.” I took two models and two bags with some bits and pieces with me. And in Kyiv I was met by a million old friends, human rights activists. And they convinced me to move here, promised to help me settle here. And I thought, I am 48, and if I wait till the war ends, my life will just end without any creative work in it.

I moved here, and I don’t regret it. I rent a room in the suburbs. I make costumes all the time, sew sequins on them like a bee. I sell my ties and costumes on the Internet — I don’t sell many, but they are expensive, because each of them have 60 to 200 hours of handiwork behind them. I already have my modeling school. The latest show was in December. I am sure that being a great manipulator I’ll somehow sell 300 tickets to them. What else do I need?

Photo: Andrey Boyko, especially for Bird in Flight

When did you understand that you don’t need much to live comfortably?

I realized that people who have a lot also give a lot. And I don’t want to wake up with an alarm clock. What’s the point of living then? Why do you need those thousands of dollars, if to earn them you have to work at 6am, smile to everyone around you, and wear a ‘dress code’? I like it better waking up at 10am and doing what I like.

I was lucky to be born in a large and friendly family, and although my brothers and sisters were fighting for a piece of bread at the table, our mom subscribed to magazines for us, such as the Young Naturalist. We grew up in poverty, but also in love. I had this vaccination during my childhood, and now you can’t scare me with $100 a month.

Did you ever feel you were a loser?

Never. I just don’t look up to anyone. I think that people need to try to fit in less, because psychiatric disorders, depression, suicide often happens because people are striving for some ‘normalcy’, and don’t value or love themselves. “Ivanova drives a Porsche, and I ride a bike. I am a loser, I will kill myself.” — what kind of bullshit is this? Life is full of beauty and ends quickly.

I sometimes look at myself and this: “My God, I climbed out of such a hole, I am an entirely uneducated person, but I have already traveled all over the world, all magazines write about me — how did I manage this?”

I know that I have more than I deserve, because I don’t put any effort in it at all. This means that there is an alternative way.

Are you trying to show this way to other people, to your daughter?

My daughter is studying to be a lawyer — she followed in her mother’s footsteps. She wants to earn more, the way her mother taught her (in everything else, my ex-wife and I have the same views on raising children). I know that I can’t make people earn less. Nobody will listen to me. But I want to at least show them that you can live on $100 a month and be happy.

Are you afraid to change with age?

I think that to be an old experienced hyena is gorgeous.

Tell me about the people you are now doing Orchid with.

They are entirely random people who come to me after reading an ad and have no idea what they will be doing here. I post ads on the Internet and in newspapers that I need people for fashion theater. 90% of those who come have no idea what it is and have never seen my shows. I have to break each and every one of them, cheat and economize on truth. But I am used to this. Only for one of ten models my theater is a conscious choice. They are, for instance, artists who now take part in fashion shows: Ania Shcherbina, Valia Petrova, and Antigona.

What are your plans?

I will be doing creative works, whatever it takes. I will be selling my costumes, create images and give them to the world.