“I Still Can’t Believe I Was There”. Yevhen Maloletka Talks About Mariupol and His Photos That Shocked the World

Documentary photographer Yevhen Maloletka is one of the most prominent Ukrainian photojournalists. He documented the Revolution of Dignity and hospitals during the Covid-19 pandemic. He cooperates with Associated Press. On February 24, together with Mstyslav Chernov, he was in Mariupol, documenting the life of a city during the escalation of the military conflict in Ukrainian Donbas. The two photographers spent three weeks there, capturing the beginning of the war and the Russian military shelling of one of the hospitals. Maloletka’s photos became the symbols of Russian full-scale aggression and turned him into a star.

In this interview, Yevhen describes how the war has changed his career, how he escaped the fear of death, and what one has to do to cope with things they saw in Mariupol.

You were named a photographer of the year by the Guardian. Does it make you feel happy?

That’s very pleasing to me. It’s good to know that Ukrainian photography has finally found its place in the world. Ukrainian photographers proved themselves to be no worse than international ones and can now reap the rewards of their work.

There was no acknowledgment before the war, wasn’t there?

Back in the day, it was hard for Ukrainian photographers to make their way into the international market. We’re living on the outskirts of the world, we don’t have big and well-known media outlets in our country. But there are many photographers here, military photographers in particular, so the competition is intense. My photos became known because of Mariupol. They stand out because they represent unique footage of historical events. That’s what pushed my name to the top of the list.

Every great photographer has their main topic. It’s what they are known for and remembered postmortem. It seems like Mariupol is your big topic.

I would really want to have more than one topic, it’s always good to have some room to grow further. And Mariupol is not only my main topic but my personal excruciating pain.

I have this feeling that international outlets usually send foreign photographers to document the war instead of hiring Ukrainian photographers. Do you agree with that?

It’s hard to say. I received requests from international media long before the war. And now, quite a few editors of international media asked me to recommend a Ukrainian photographer.

Who did you recommend?

Kostia Liberov, who is a great photographer and who is not afraid of getting right into the eye of the storm. If a photographer wants to take photos, they will find a way to do it. And sooner or later, international media will come to them and offer cooperation. But photographers have to show what they can to make it happen. And it does not necessarily mean putting yourself in danger. War has many sides and angles that photographers can document.

Another thing is that documenting the war is an expensive pursuit. You’ve got to fill the tank of your car with something, you’ve got to pay for your hotel. In that sense, things are easier for Ukrainian photographers now, because we’re working in our home country. We can go without fixers, hotels, and even without a car. It saves us a lot of money.

If you chose not to put yourself in danger, which sides of the war would you document?

I would show the deceased, the tortures, and the war crimes. There are a lot of topics. But I’m not encouraging people to work on a specific topic. I think what matters most in our job is personal motivation and photographers’ interests. This is the reason why editors often ask photographers why they decided to capture this specific event or story.

How do you answer that question?

I started documenting the war eight years ago. It’s what I know and it’s what I can do the best. My photos are my mediators to speak out and tell the world what’s going on here.

Mariupol, March 2022

A funeral of the photographer, Max Levin, Kyiv, April 14, 2022

President Volodymyr Zelensky interviewed by Associated Press in Kyiv, April 9, 2022

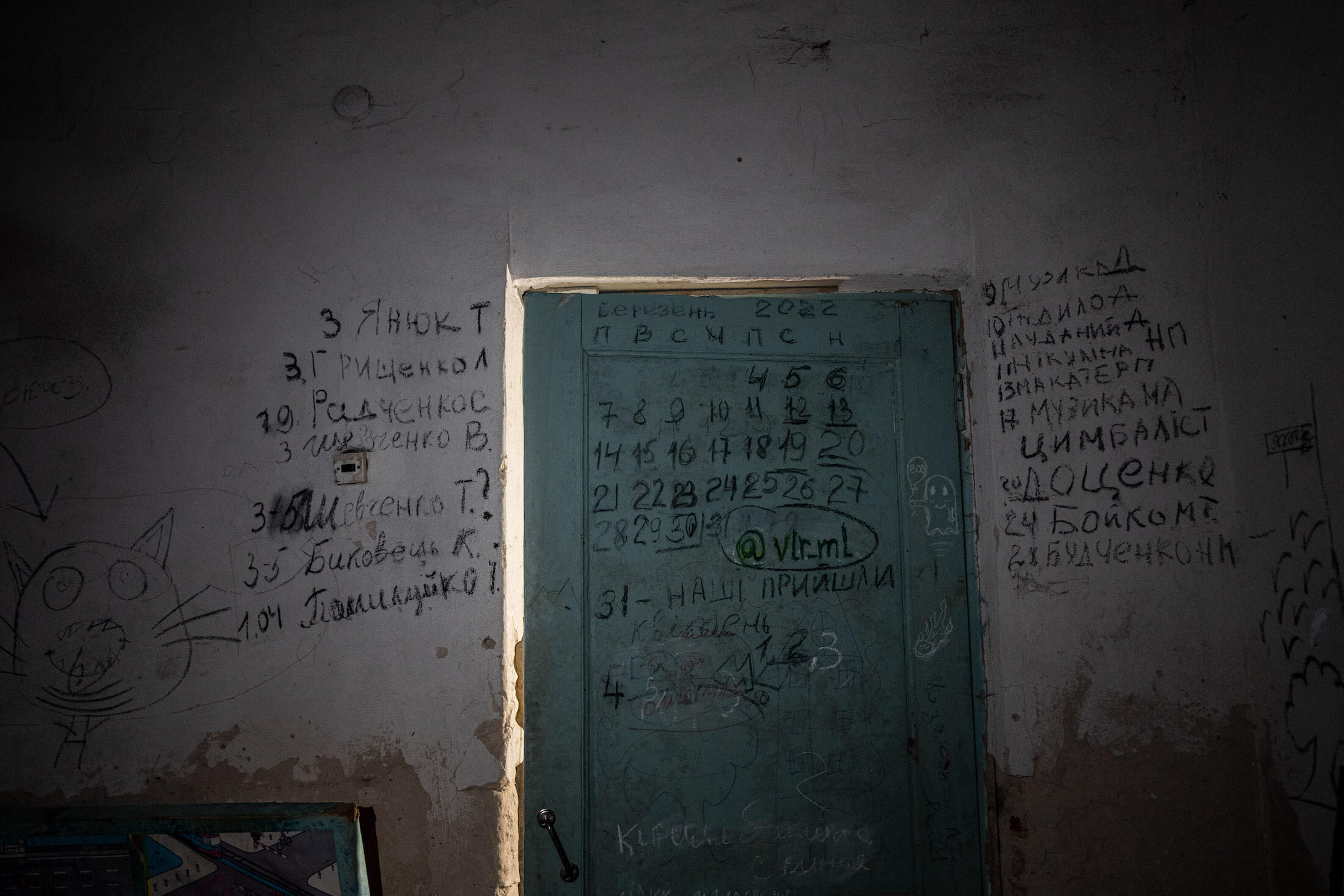

Almost all the residents of the village of Yagidne, which is about 350 people, were kept by the Russians in the school basement. Local residents made an improvised calendar on the door and wrote 10 names of people who died in this basement. Yagidne, April 12, 2022

A school principal Iryna Khomenko walks down the school’s corridor, which was damaged as a result of an air strike. Chernihiv, April 13, 2022

12-year-old Danik Rak holds a cat in his arms, standing on the ruins of his house, which was destroyed as a result of shelling by the Russian military. After the shelling, Danik's mother's leg was amputated. She also suffered abdominal injuries. Chernihiv, April 13, 2022

If you chose not to put yourself in danger, which sides of the war would you document?

I would show the deceased, the tortures, and the war crimes. There are a lot of topics. But I’m not encouraging people to work on a specific topic. I think what matters most in our job is personal motivation and photographers’ interests. This is the reason why editors often ask photographers why they decided to capture this specific event or story.

How do you answer that question?

I started documenting the war eight years ago. It’s what I know and it’s what I can do the best. My photos are my mediators to speak out and tell the world what’s going on here.

What do you call yourself, a documentary or a military photographer?

A documentary photographer.

Can documentary photography be objective or is it a utopia?

I try to be objective in my work. But, in general, documentary photography can’t be objective or subjective. It documents a fact that has already happened.

Ukrainian photographer Maksym Dondyuk thinks that documentary photography is still manipulative at its core. When taking a picture, a photographer cuts off what’s left behind the camera and shows only things that he wants us to see. What do you think about it?

For sure, a photographer can’t take a 360-degree picture. Every image has a frame and we only see what’s inside. If we are talking about objectivity in a wider sense, it was possible eight years ago. Back then, photojournalists were documenting both sides of the war. First, they took pictures of Ukrainian soldiers, then they crossed the frontline and photographed those from the so-called People’s Republic of Donbas. Every international media did that. But we can no longer do it now, so photojournalists capture only one side of the frontline on their camera. Now, what’s the difference between journalism and non-journalism? A journalist documents facts, but never interprets them. Russian propagandists interpreted even our photos from a maternity hospital in Mariupol.

What was your reaction when they accused your photos of being fake?

I laughed at it at first, but then I realized that their propagandistic machine is now up and running in full swing. They pushed the narrative about staged images with every instrument they had — through their Ministry of Foreign Affairs, embassies, Facebook, and Instagram.

That’s not the first time they do it. During the war in Georgia in 2008 a photographer named Glib Garanich captured an ambulance driver who held his brother’s dead body in his arms. And the Russians launched an information attack, targeting Glib. They published discreditable materials about him, claimed that his photos were fake. During the war in Syria, when the Russians used chemical weapons, somebody took a picture of a boy in a hospital. Russian propagandists found the photographer afterward and said that the photo was staged. What’s interesting is that they interpret videos a lot less.

What’s your opinion about the photographers who received accreditation from Russia?

If not for them, we would never know what was going on there. And it’s crucial to see and know.

It’s a difficult question. On one hand, it’s propaganda, but on the other hand, we only know about concentration camps and thousands of executed Jews during World War II because there were propagandistic photographers, who documented it all.

I’m just a photographer. I look at this question from an informational standpoint. Here I see a picture that shows what’s left behind after shelling. I can take something from it and that’s important.

A rescuer helps an elderly woman with a disability get on the evacuation train. Pokrovsk, April 26, 2022

Teenagers look at the crater after a Russian missile attack in the schoolyard. Dobropillya, April 28, 2022

People in a bus during evacuation from Liman, April 30, 2022

Nataliya Pototska from Vasylivka with her grandson Matviy cries in the car while waiting for registration at the immigration reception point. Zaporizhzhia, May 2, 2022

Ukrainian Su-25 aircraft after the attack on Russian positions. Donetsk region, May 10, 2022

Rescuers are sorting through the rubble of a school destroyed by a Russian strike. Kharkiv, July 4, 2022

Let’s talk about Mariupol. How long you and Mstyslav Chernov were there?

Twenty-one day.

Were you scared to go there?

No. We came to Mariupol an hour before the war started. Back then, it was hard to imagine what was going to happen there. I mean, people didn’t believe that the war was coming. We felt that something was happening but we were not ready for the scale of it.

Were there times when you said your goodbyes to life?

What’s the point to say goodbye to life? It’s better to try to figure out, how to get yourself out of this shit and keep taking photos. Sometimes, I was really terrified. The city suffered under enormous artillery fire. You would spend half an hour lying on the ground, hearing projectiles exploding around you and aircrafts roaring above you, and having absolutely no idea what to do next.

The scariest moment was when we came to the hospital to check how pregnant women and women in labor were coping there. The building next door was captured by the Russians, the street was filled with tanks. When we were in the hospital, we were sure that our troops would fight off the attack and kick the Russian soldiers out of the city. We were wrong. Russians remained in that neighborhood and we happened to be encircled. There was no way to run. The only thing we could do was to wait. We were lucky that a special police group came for us the next morning. They took us out.

Who stayed in the hospital?

Doctors and patients.

How did you feel about leaving them behind?

Russians wouldn’t have hurt doctors, but they would have taken us captive because we were informational enemies for them.

Were they looking for you?

That’s what a police officer told us. It’s impossible to check this version but I strongly believe that they would have hunted us down if we stayed in Mariupol. They would have looked for us at every checkpoint. We left the city in one of the first waves of refugees and we went through minor checkpoints. That’s what saved our lives.

What would they do to you if they caught you?

Well, it would have been no fun for us. I think they would make us record a video and “confess” that our photos were fake.

You’ve spent three weeks in Mariupol. I think you were under a lot of stress. Did it impact your health in any way?

That whole time I was operating on sheer adrenaline. But when we came back home, I had to pull myself together. I started to realize everything that happened in Mariupol. It’s a long process.

How does it go?

You always keep an eye on what’s going on in Mariupol. You recognize streets that you’ve walked and locations where you’ve worked. You try to figure out which buildings have been seized by the Russian troops by now and where the fight still goes on.

We kept in touch with the guys who stayed in Mariupol, asked them where they were, who has left the city and who has stayed. Mariupol doesn’t let me go. But I still can’t believe that I actually was there.

Have you considered that you might have PTSD?

PTSD symptoms take time to show, I don’t have them yet. But it’s important to take care of yourself and watch your emotional state. You need to talk to people, to tell them what you saw and heard in Mariupol. If you bottle your feelings up, you will end up having bad depression, that’s for sure.

Do you talk about those things enough?

Yes, here I am talking to you. It’s not the same thing as talking to a psychotherapist but it’s something.

I already get overwhelmed by my thoughts sometimes. I see young men dying every day, I see civilians and kids getting killed under shelling. I don’t understand what’s the point of it all. What motive does Putin have? What does he want? I have no answer.

When we talked in spring, you were, let’s say, quite pessimistic about the end of the war. How do you feel now?

I am pro-reality. And I think we should be ready for the worst. I’m not a military expert but I talk to a lot of people and know what’s going on. I know what’s going on in the army, what number of casualties we have. I know that ten bodies are buried in Kharkiv cemetery every day. And that’s only Kharkiv. How can I feel about it? We pay an enormous price for every win that Ukraine achieves.

Ukrainian paramedic Yulia Paevska, better known as Tyra, poses during an interview with the Associated Press (AP). A well-known Ukrainian paramedic was captured by Russia on March 16. She was released on June 17. In March, AP journalists managed to get video tapes out of the city, which showed Tyra and her team rescuing local residents and wounded soldiers, including Russian ones. Kyiv, July 8, 2022

Ukrainian servicemen fire from a Bulgarian SPG-9 during exercises at the training ground. Kharkiv region, July 19, 2022

Sabina cries over the body of her husband Artem Pohorilets, who died after the Russian attack on the Barabashovo market. Kharkiv, July 21, 2022

A Ukrainian serviceman with the call sign Peter rests on mortar shells on the front line. Kharkiv region, July 22, 2022

Vitaliy Kim, the head of the Mykolaiv Regional Military Administration, is talking on the phone. Mykolaiv, August 5, 2022

Father Andriy prays for the unidentified dead killed by the Russian military during the occupation. 21 bodies were exhumed from the mass grave. Bucha, August 17, 2022

Do you follow up on what happened to the people from your photos in Mariupol?

Yes. We recently worked on material about an “OLIL” hospital. It’s a Mariupol hospital, which is now operating in Kyiv. Part of the staff are doctors from Mariupol. We met doctors and surgeons, with whom we worked back in March. They are like family to me. I gave them a photo of us together, which I took on March 11 when the hospital and the neighborhood around were already blocked by Russians. There was no way to bring the injured in, so the surgeons had some free time on their hands and that’s when I took that picture.

What happened to Marianna Vyshemirska, a woman in labor from your famous photo?

She caused us, the photographers, a lot of trouble. Russian propaganda used her to whitewash their own role in the story with the shelling of the maternity hospital. She gave an interview and she accused our side. We talked to her in the hospital, after the shooting, when I was working on material about her. I don’t judge people, but I made my conclusions about her. I think she did the same. When we were talking, she confirmed the fact that she was pregnant and was at that maternity hospital. Because in the beginning, Russian propaganda claimed that her pregnancy was also staged. When she told me that she “wasn’t into politics”, I had a weird feeling as though this phrase came straight from 2014. I told her: “It’s not about politics. We are at war and the building that you’d been in was demolished in pieces. Can you give a comment about this whole situation because people say that it was staged?”. When I walked out of the door I knew for sure that if Russians found her, she would tell them what they wanted to hear.

Now she has a Telegram channel, where she promotes the “Russian world”. But I think someone else writes the posts for her. It’s hard to believe that a person who said she “wasn’t into politics” suddenly got a hand in writing political news.

Do you think Russians pressured her?

I’m sure that they didn’t have to.

Mariupol, March 9, 2022

What happened to the husband of Iryna Kalinina, a second girl with a thigh injury, who died soon after the shelling?

It’s a horrible story. Iryna had thigh and stomach injuries. The doctors took out her baby and it was already dead. I talked to her husband in November. He spent a lot of time searching for Iryna among dead bodies in the hospital. When he found her, his neighbor helped him bury her. He lived in Mariupol until summer and then he fled the city because the situation became unbearable.

He is now in England, trying to start it all over. He told me that alcohol helps him wash out that horror.

Mariupol, March 9, 2022

Another photo that is impossible to forget is a picture of a father who hugs the dead body of his son covered with a sheet.

The father’s name is Serhiy, he is a sailor. I talked to him over the phone. His son was buried in a mass grave. Afterward, Serhiy took his family out to Canada and went to sea. He told me that he did it to distract himself and forget about his grief.

There was another picture of a young man and woman who ran into the hospital with an injured child. The child was injured when their house was shelled. The man, her neighbor, brought the child to the hospital, but the kid died anyway. Now they are in Vinnytsia. They have recovered a bit but not completely. Just think about it, they lost their son. It’s a horrible tragedy.

Overall, people from my photos try to forget what happened to them. They try to distract themselves from all this shit that is still happening. And many succeed in that. Life goes on, and you have to live it. There is no other choice. You see, I have the small privilege of talking about things that happened to me. It’s not only a privilege but it’s also a mission. As one person told me, people had to see the terrible things that happened in Mariupol. And we just were there by chance, although we had an opportunity to leave the city. I still regret the fact that we left early. We should have stayed longer and shown the theater of drama. But it is what it is.

Serhiy, the father of the teenager Ilya, cries over his son's dead body lying on a stretcher in the maternity hospital converted into a medical ward. Mariupol, March 2, 2022

How long could you have stayed in Mariupol?

Not too long. Hypothetically, we could have gone to Azovstal, but we had no contacts there.

Do you have a lot of unpublished material from Mariupol?

No, we published almost everything. To tell you the truth, we weren’t filming that much in Mariupol as one can imagine. It was dangerous to go outside and we spent most of our time indoors. Besides, we tried to save batteries and gas. Our photos show just a small part of what was happening in the city. Just imagine what was in other parts of the city.

They say, not everyone in Mariupol supports Ukraine. Is it true?

Yes, it’s is a complicated city in that sense. Picture this, we are under fire, people run out of their burning houses and cry: “Ukrainians are shelling us!”. Or another example. There was a fire in the nine-story building. People run for their lives and hide. One woman tells me: “You are taking pictures but you’d better go and bring the firefighters”. I tell her that no one is coming, firefighters got under Russia’s attack yesterday. And she says: “Ukraine is bombing us”.

Why do you think people keep believing that Russia is their friend despite Russian missiles flying above their heads?

It’s hard to say. Not everyone thinks that way. Some people just didn’t understand what was happening. They hid in basements and had no Internet and information.

People look at a house destroyed by Russian troops. Nikopol, August 22, 2022

A man rides a skateboard past destroyed Russian military equipment in the center of the capital. Kyiv, August 24, 2022

Exhumation in Izyum, September 16, 2022

7-year-old Veronika Tkachenko holds a missile fragment that hit her family's house. Izyum, September 25, 2022

Mattresses on the floor of a cell in the basement of a police station used by the Russian military for torture. Raisin, September 22, 2022

A cat on a chair in the kitchen in the Pishchan Monastery. Izyum, September 21, 2022

A military prosecutor examines fragments of Russian multiple-launch rocket systems that were used to attack the city. Kharkiv, December 22, 2022

A wife looks at the grave of her husband, Serhii Klymenko, a Ukrainian serviceman who died on the front line from Russian shelling. Kharkiv, December 23, 2022

Did world fame change anything in your life?

It changed a lot. Our photos got more attention. I received inquiries from people who wanted to help Ukrainians. They saw my photo of a child or read the capture and offered their help. I receive a lot of messages from abroad. I give them contacts of people in need and it all works out. It’s good to know that your work helps people who really needed that help.

Recently, representatives of the territorial center for providing assistance to socially vulnerable citizens asked us to buy them a generator. A donor gave us money, we bought a generator in Lithuania, I delivered it to Izyum. This is exactly why we do what we are doing. It’s not for the sake of seeing your photos in print. Everyone is interested in Ukraine, so our photos make it to print anyway.

Cover photo: Mstyslav Chernov. On photo: Evgeniy Maloletka.

New and best