Where Did the Somali Pirates Go?

In 2008, they hijacked 42 ships and earned about $80 mln in ransom. That year a Russian-born London obstetrician Denis Tsepov wrote on his blog: “A strikingly beautiful young woman from Somalia arrived to give birth tonight wearing black and large diamonds. She was accompanied by a group of about seven cheeky fellas in Comme Des Garçons suits. After I helped her birth a beautiful boy, I got bolder and asked: “So guys, what do you do for a living if I may ask?” They said: “We are just sailors from Somalia, and why are you asking?”” No matter how fictional this story sounds, it is an accurate reflection of an early romantic myth about the Somali pirates that faded even faster than their trade was extinguished.

Coercion to Piracy

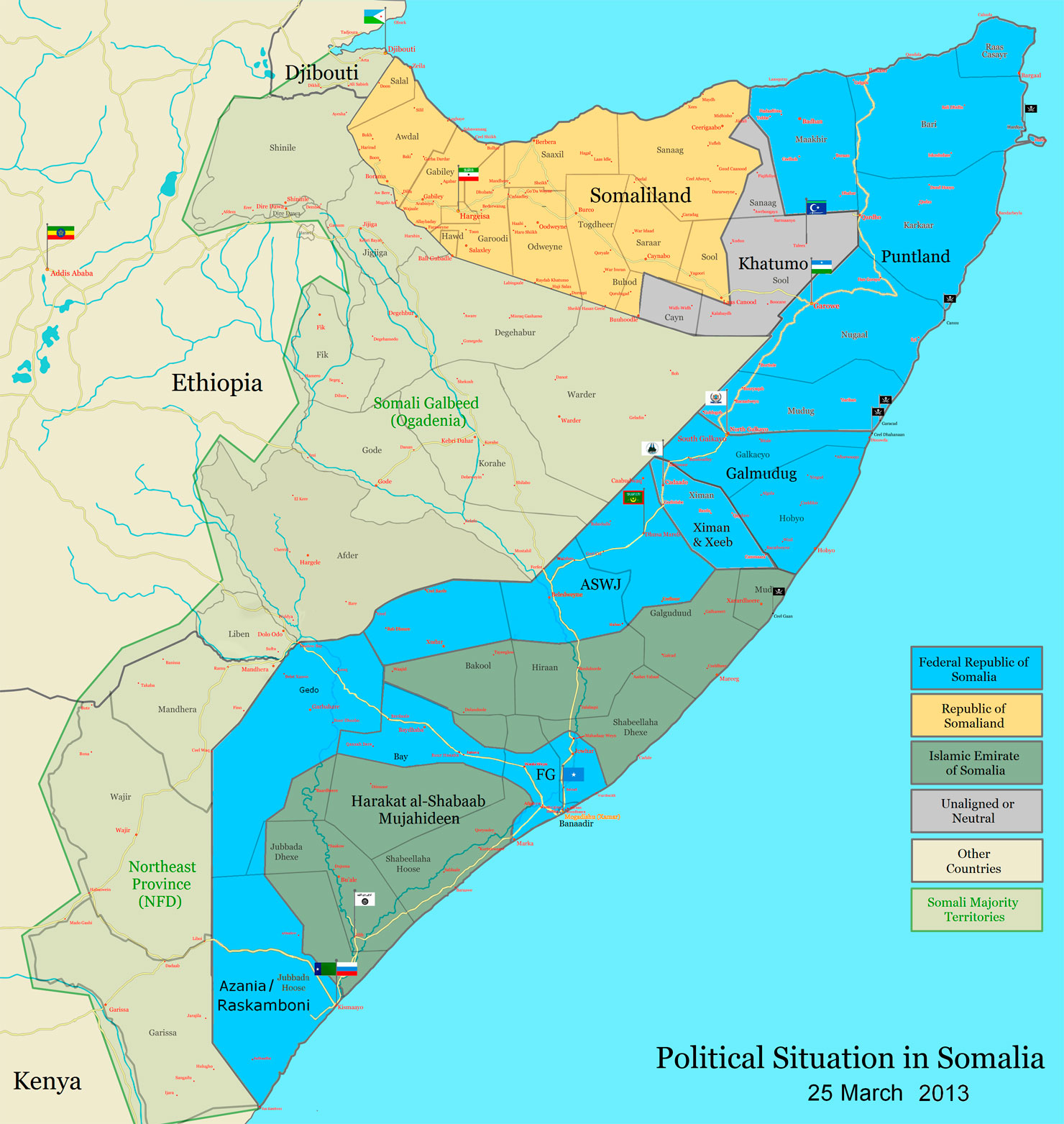

By 2005, when pirates hijacked the first big international vessel in the Gulf of Aden, the war in Somalia had been going on for 30 years. The war with Ethiopia was followed by a series of uprisings, which literally tore the country to pieces, controlled by rivaling warlords.

The poachers made use of the lack of coast guards. Trawlers from all over the world were scooping $300 mln a year worth of tuna, shrimp, and lobsters. Moreover, the companies with connections to Italian mafia started dumping toxic waste into local waters. This had a negative impact on the only source of income of extremely poor Somali fishermen. After several attempts to ‘tax’ the international waste-throwers and poachers, they started a really profitable business.

The Tactics of Attacks

Their equipment were walkie-talkies, and later GPS-navigators. Their intelligence was a bribe to the official in the Kenyan port. Two wooden boats with 60 hp outboard motors that speed up to 25 knots (about 46 km/h) and catch up with a freighter or a tanker in international waters.

To make the captain slow down, the pirates fire warning shots from their rusty Kalashnikovs in the direction of the deckhouse and show that they are ready to use the grenade launcher. They look for a deck that is low enough for them to throw up a ladder and climb on deck. They take over the captain’s bridge, and threatening with weapons, lead the vessel to their harbor. If the ship has a deck higher than 8 meters and can go faster than 18 knots (33 km/h), it stays unassailable.

It happened very rarely that the Somalis moved from threats to real violence. Between 2008 and 2012 when they hijacked 170 vessels with 3,400 crew members, they killed 25 sailors. Another 37 starved to death or committed suicide in captivity.

Business Model

2010 was the best business year — the ransom for 47 hijacked ships totaled in about $238 mln. The bigger part of the revenue went to the investors of the expeditions: local clan leaders and craft owners. A regular sailor received only $30,000–70,000 from an average ransom of $2.7 mln.

The negotiations with vessel owners went on for several months. During this time the pirate crew lived on the trophy, and the investor deducted the cost of food, prostitutes, communication, and kath, a local drug, from the crew’s share. Few ordinary sailors went ashore with over $10,000–20,000, but even this is a substantial amount of money for a country where the average annual income is $300. In 2009, The Washington Post, citing a Somali who was asked about the difference between pirates and militants in the internal areas of the country, noted that they appeared happy and healthy.

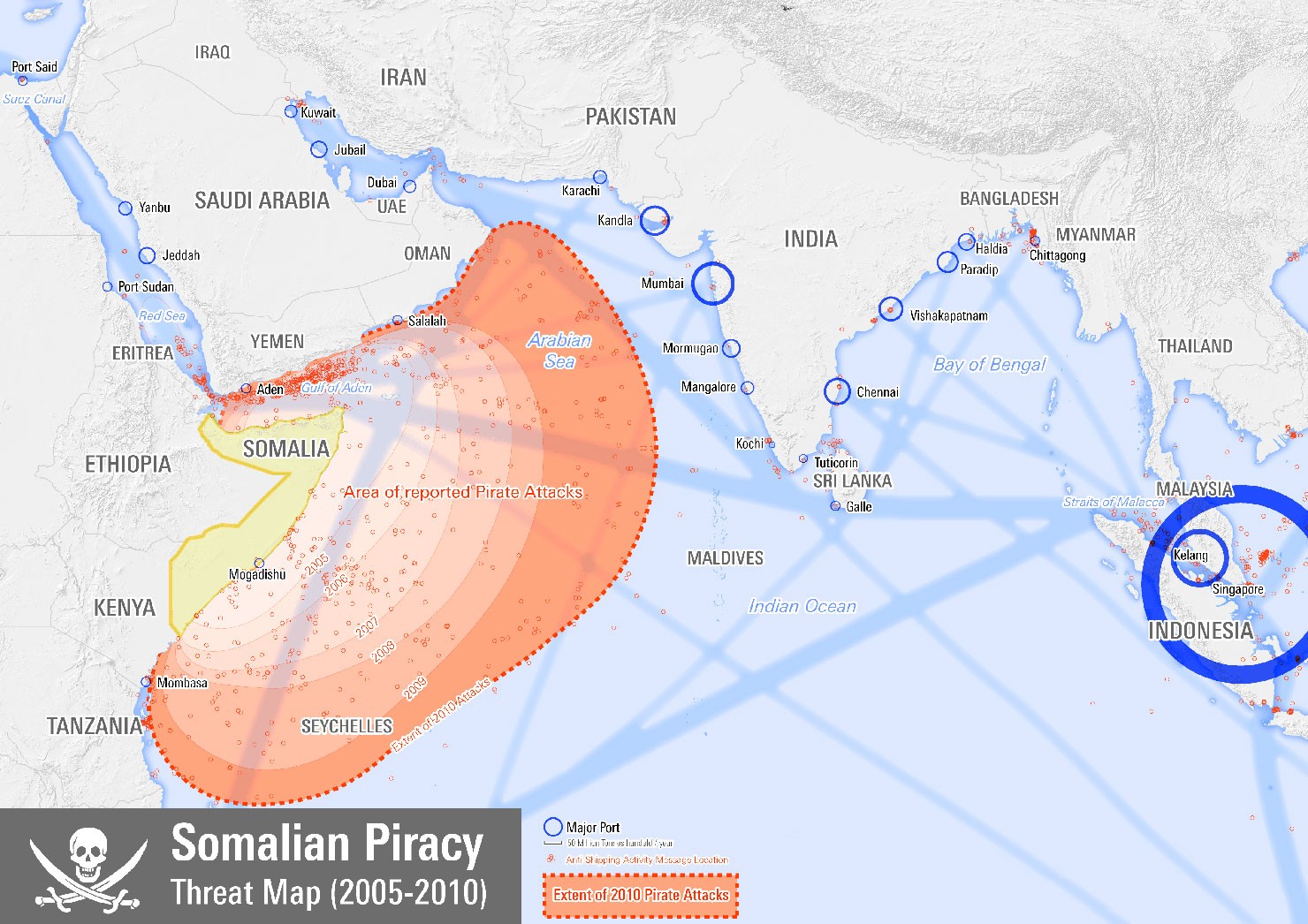

Losses for the Shipping Industry

42 hijackings in 2008, 46 hijackings in 2009, 47 in 2010, 28 in 2011 — each of them got a lot of coverage in the media, creating the impression of a serious threat to the international shipping industry. However, not fewer than 21,000 merchant ships travel annually from the oil states of the Persian Gulf to Europe and back past Somalia. Even in the best years the Somali pirates were a threat to only 0.1% of them, and the losses that the vessel owners suffered were mainly caused by fear.

As of 2011, the increase in the insurance value cost the maritime industry an additional $635 mln, creating routes that were further from the coast and additional expenses on fuel — $580 mln, expenses on fuel to speed up to the safe 18 knots — $2.7 bln, installation of protective equipment and hiring armed guards — more than $1 bln.

The Best Known Cases of Hijacking

September 25, 2008. Freighter Faina with a Ukrainian crew was on its way to bring 40 T-72 tanks, grenade launchers, and antiaircraft guns to Kenya. The ransom was $3.2 mln.

April 8, 2009. Container ship Maersk Alabama under a US flag. The crew locked themselves in the engine room, blocked the controls, and later took one of the Somalis hostage. The three others sailed away on a rescue boat with Captain Phillips as a hostage. The day after all of them were shot by the US Navy Seals snipers, and the captain was not hurt. In a movie made based on this story he was played by Tom Hanks. Two years after, the unit of special forces that took part in this operation will kill Osama bin Laden.

The figures present Google searches for ‘somali pirates’. The highest point is the story Maersk Alabama freight ship captain Richard Phillips.

November 15, 2008. 330 m supertanker Sirius Star carrying 2.2 mln barrel of oil valued at about $100 mln. This was the biggest ever catch for the Somalis, with a ransom of $3 mln.

May 5, 2010. Oil-carrying vessel Moscow University. The Russian crew barricaded themselves in the hold and called the military ship Marshal Shaposhnikov for help. The marines stormed the ship. The official version says that the pirates were placed in an inflatable boat with a small store of water and food, but they could not reach the shore without navigation. The unofficial version says they were shot then and there.

May 10, 2012. The hijacking of a Greek supertanker Smyrni carrying 1 mln barrel of oil. According to the pirate leaders, they secured a record $9.5 mln.

Military Operation

Somali piracy was a good reason to improve international cooperation to protect the merchants and at the same time ensure the military presence on an important oil delivery route: warships from 21 countries are now hunting for the bandits in the boats with outboard motors. This is the largest coalition of fleets of different countries in history and the first ever case when all the permanent members of the UN Security Council — US, Russia, Great Britain, France, and China — are all united against a common enemy.

It is hard to say whether the participants of the operation are reaching their unspoken goals, but the warships are not adapted to countering the near-shore piracy. In a year that they started patrolling in 2008, the number of attacks on merchant ships increased twofold. The balance of power was changed later only due to drone surveillance of the sea. Every success of the patrol was documented, which emphasized how unequal the forces were.

A Win on the Shore

A private initiative became a successful alternative to the expensive and ineffective effort of the state systems. In 2012, 80% of the merchant ships that passes by Somalia had armed guards on board. It is legally impossible to enter the ports with weapons, so private military companies have floating bases in the area, where the ships can take the guards on board and later part with them when they have passed the dangerous district. A team of 3 to 4 guards costs between $28,000 and $38,000, which is an order lower than a minimum ransom. The pirates have never succeeded in hijacking a guarded ship.

However, the main victory was achieved on the shore and was paid for by one family — the Al Nahyans, the ruling family of Abu Dhabi emirate. The oil sheiks took the threat to the tanker fleet seriously and became patrons of the Somali province Puntland with 1.5 million population, which currently lives as an independent state. Some time ago, the majority of pirate bases were located on the territory of Puntland.

The Al Nahyans had a failed experience of creating their own army — “Muslims don’t want to kill other Muslims” — they hired Erik Prince, a former CIA agent and the creator of Blackwater / Xe Services / Academi, a leading international military company, to advise them. He has been building the armed forces of the United Arab Emirates with Colombian contract soldiers. Since 2010, for the $50 mln provided by the sheiks, he has overseen a special unit called the Puntland Maritime Police Force special unit in Puntland. The instructors and commanders for the Force are mercenaries from South Africa, who are good at fighting the guerrillas and are known for their harshest methods of training and maintaining discipline — the UN inspectors have documented cases of beating and murdering of the cadets.

Their work resulted in creating one of the best military units in this part of Africa. A party of 1,000 soldiers who have crafts, light aircraft, and helicopters at their disposal managed to destroy the ground bases of the Somali pirates and their entire business operation in two years. Since May 10, 2012 they have hijacked only one vessel — an Iranian poacher, which nobody wanted to protect.

“This project was conceived by and executed by what we would call pariahs, people who are not part of polite society, but it remains one of the most efficient and productive solutions to the problem of piracy,” according to Robert Young Pelton, author of Licensed to Kill: Hired Guns in the War on Terror.

In 2010, the largest jail for pirates in the world funded by the UN, which can house 500 inmates, opened in Puntland’s capital Garowe. It is filled to capacity. Currently the waters of Nigeria and Guinea are considered the most dangerous for shipping near the shores of Africa.