Five Top Scientific Discoveries of 2016

Waves of the Year

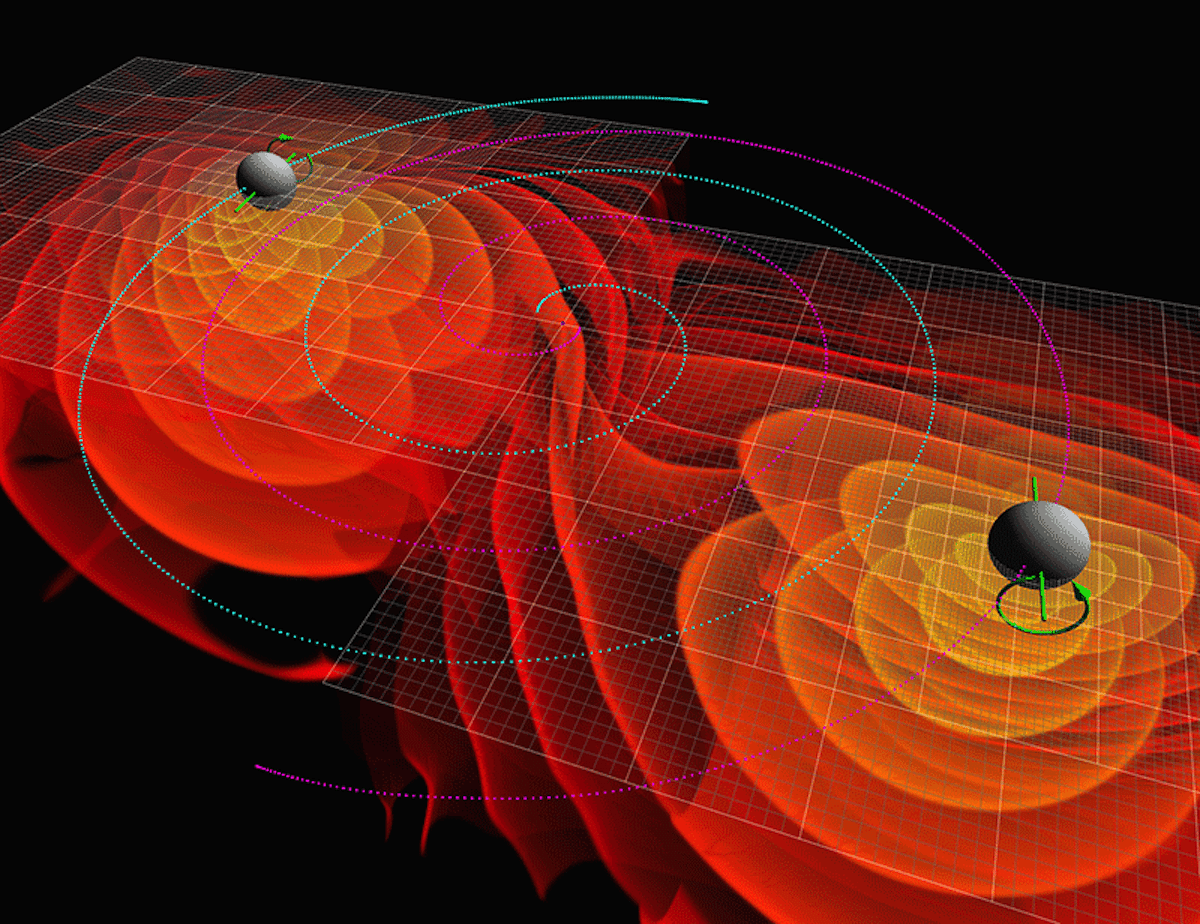

I bet that many centuries later our descendants will remember 2016 not for celebrity deaths or political turmoil — 2016 will remain in history as the year when one of the most important predictions made by Einstein one hundred years ago was confirmed: it turns out that the moving masses cause space–time disturbance that exists independently from initial masses.

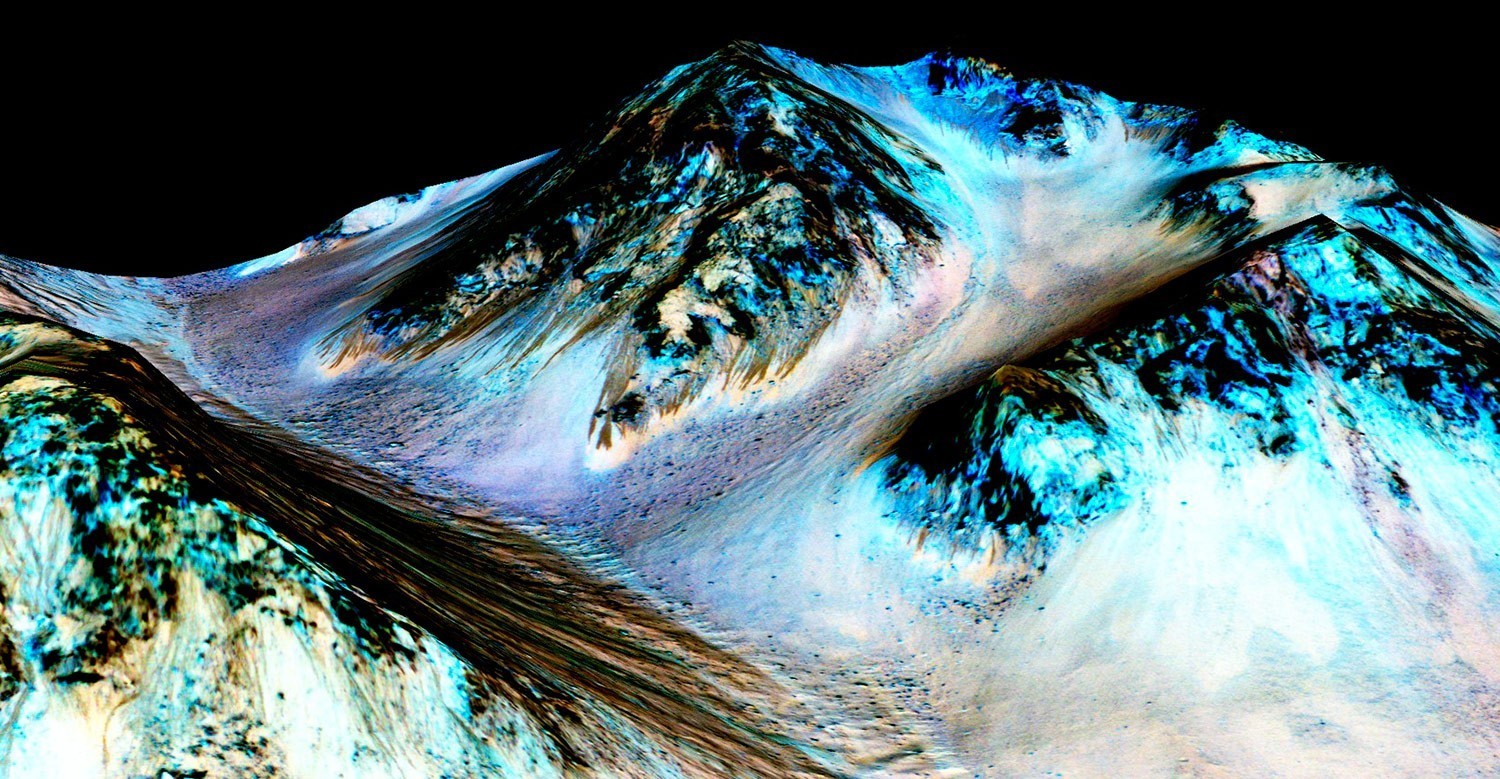

The established scientific term — gravitational waves — is rather metaphorical and allows common people to understand a complicated scientific concept through their everyday experience. Imagine that you are throwing a stone into the water — in our example, it represents a mass, such as the collision of two black holes. Falling into the water, the stone causes ripples on its surface — these waves that represent the rippling of space–time spread regardless of the object that caused them.

Gravitational waves spread across the Universe at the speed of light — the source that caused the wave, which scientists detected in autumn 2015 and made known to the public in February 2016, is located 1.3 billion light years away from Earth. At the time when the merger of two black holes that we noticed only now happened, the life on our planet existed only in the form of unicellular organisms that have not even yet mastered sexual reproduction. The scale is cosmic indeed.

Experimental confirmation of the existence of gravitational waves proved that humanity understands the processes that take place in the universe more or less correctly, which means we are on the right track, and new wonderful discoveries are waiting for us ahead.

Number of the Year

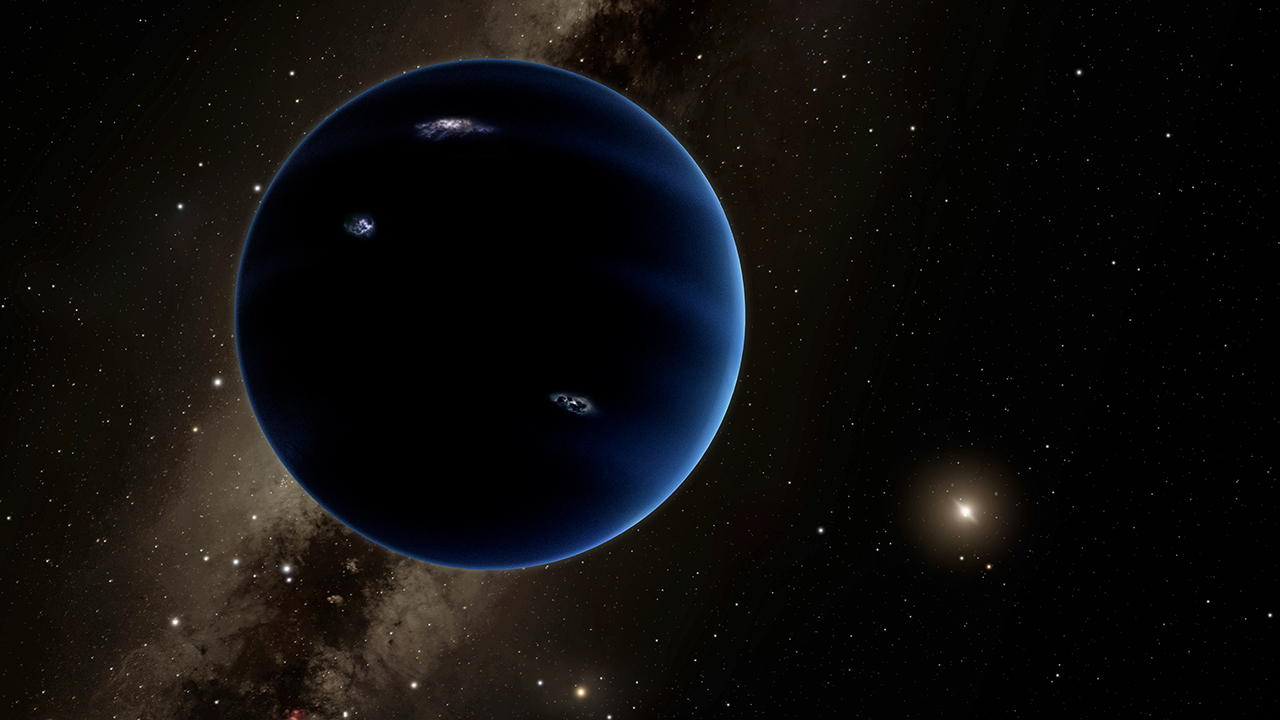

Speaking of the cosmic scale, how many planets are there in the solar system? If you are thinking nine, you either have missed all the important astronomy news of the past decade, or have followed them very closely in 2016.

For the most part of the 20th century, we considered Pluto to be the ninth planet from the Earth. However, in 2005 astronomer Michael Brown discovered a new object beyond Neptune’s orbit, which was later named Eris. Eris turned out to be either slightly bigger than (or at least comparable with) Pluto. After that, more

that orbit the Sun at a greater distance to it than Neptune

However, scientific thought did not stop at this: there were anomalies in the remote parts of our star system that suggested that a ninth planet does exist. In 2016, the same Michael Brown and his younger colleague Konstantin Batygin hypothesized that there is a planet with a mass much bigger than the mass of the Earth, that is located 20 times further from the Sun than Neptune. The calculations of the astronomers look persuasive, but to confirm their hypothesis we need to directly observe Planet X, so we can list the Brown—Batygin hypothesis as one of the discoveries of the year only in advance. In any case, news such as this one draws the public interest to astronomy and might inspire the next generations of researchers.

Exoplanet of the Year

Unlike the hypothetical ninth planet of the solar system, Proxima Centauri b, which was discovered in 2016, is a very real

And so far, Proxima Centauri b triggers bold hypotheses about the possible life forms on it. In particular, the scientists suggested that to protect themselves from ultraviolet flares of the star that is more active than the Sun the living organisms on the planet must be using fluorescence like some coral polyps do.

a planet that orbits not the Sun, but a different star

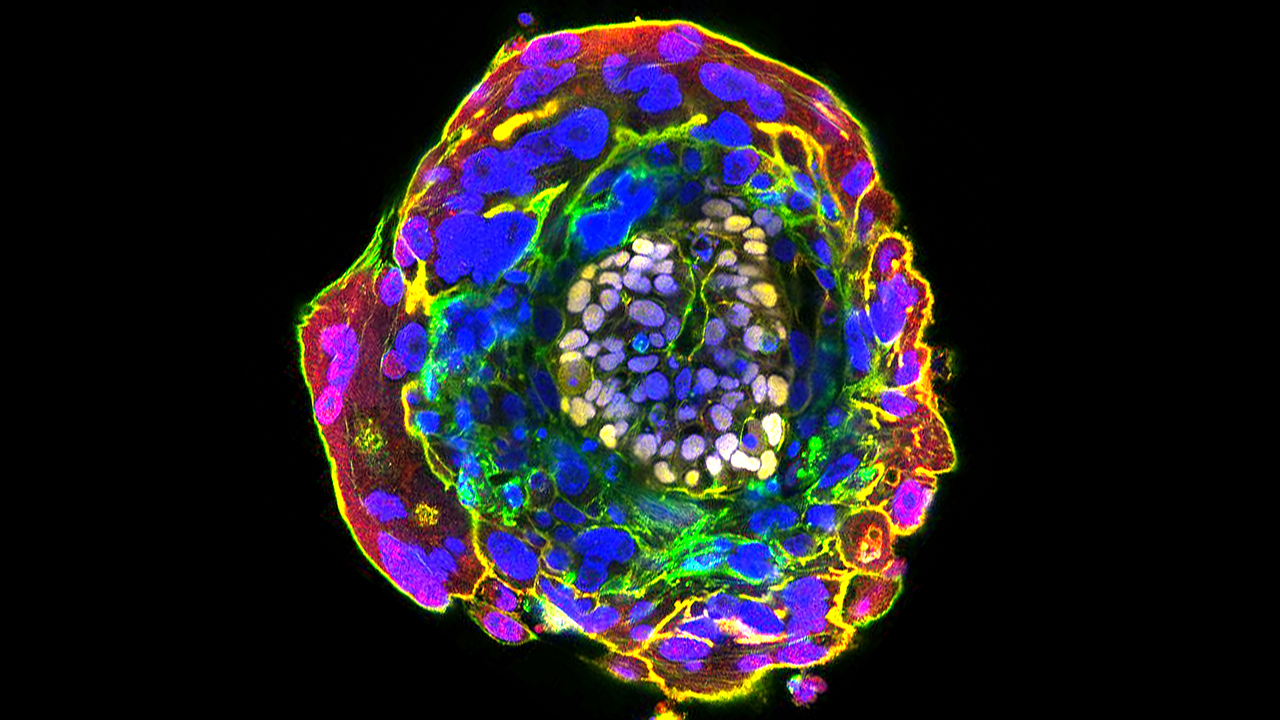

Embryo of the Year

In 2016, researchers from Cambridge University kept a human embryo alive in vitro for 13 days. This life expectancy of the embryo exceeds the previous results almost twofold. Why is this important? Earlier, scientists needed to implant the embryo into the uterus no later than seven days after the fertilization of the egg, which did not allow them to directly observe the development of the fetus at later stages. By doubling the in vitro life of the embryo, researchers receive the opportunity to study the changes on a cellular and molecular level that happen to it. The results of such observations will allow for improvement of the efficiency of in vitro fertilization in the future.

The achievement of the British scientists has already caused an ethical debate. British law currently prohibits keeping an embryo alive in vitro for over two weeks. And while the researchers did not have instruments to prolong its life in vitro for over a week, this limitation was not a concern, but now the suggestions to extend the limit might arise. In its turn, this might raise questions on whether it is ethical to experiment with human embryos that are over two weeks old.

Surprise of the Year

In 2016, researchers spent a lot of time studying monkeys — I suppose, they got too disappointed in humans. One of the most interesting experiments combines the elements of biology and a reality show, asking difficult questions about human uniqueness along the way.

For a long time scientists considered that the so-called theory of mind, that is, the ability to perceive the mental states of other beings as your own, is a typically human feature. We think about what other people are thinking: what their intentions, expectations, and beliefs are, including also if those are wrong. And it turns out, monkeys also have this quality. This was visualized best in 2016 by a Japanese/American team of scientists.

In 2016, researchers spent a lot of time studying monkeys — I suppose, they got too disappointed in humans. One of the most interesting experiments combines the elements of biology and a reality show, asking difficult questions about human uniqueness along the way.

For a long time scientists considered that the so-called theory of mind, that is, the ability to perceive the mental states of other beings as your own, is a typically human feature. We think about what other people are thinking: what their intentions, expectations, and beliefs are, including also if those are wrong. And it turns out, monkeys also have this quality. This was visualized best in 2016 by a Japanese/American team of scientists.

Video: Youtube

In another 2016 study, researchers proved that the macaque’s vocal apparatus can reproduce the sounds of human speech. So it is not the anatomy that prevents monkeys from speaking — it must be the lack of neural mechanisms that provide control over the vocal cords.

It turns out that monkeys are much closer to us than we expected: our last common ancestors must have had both the anatomic ability to speak and the ability to perceive the mental states of others.