Gastronomy Front: How Food Helps Nations Win Wars

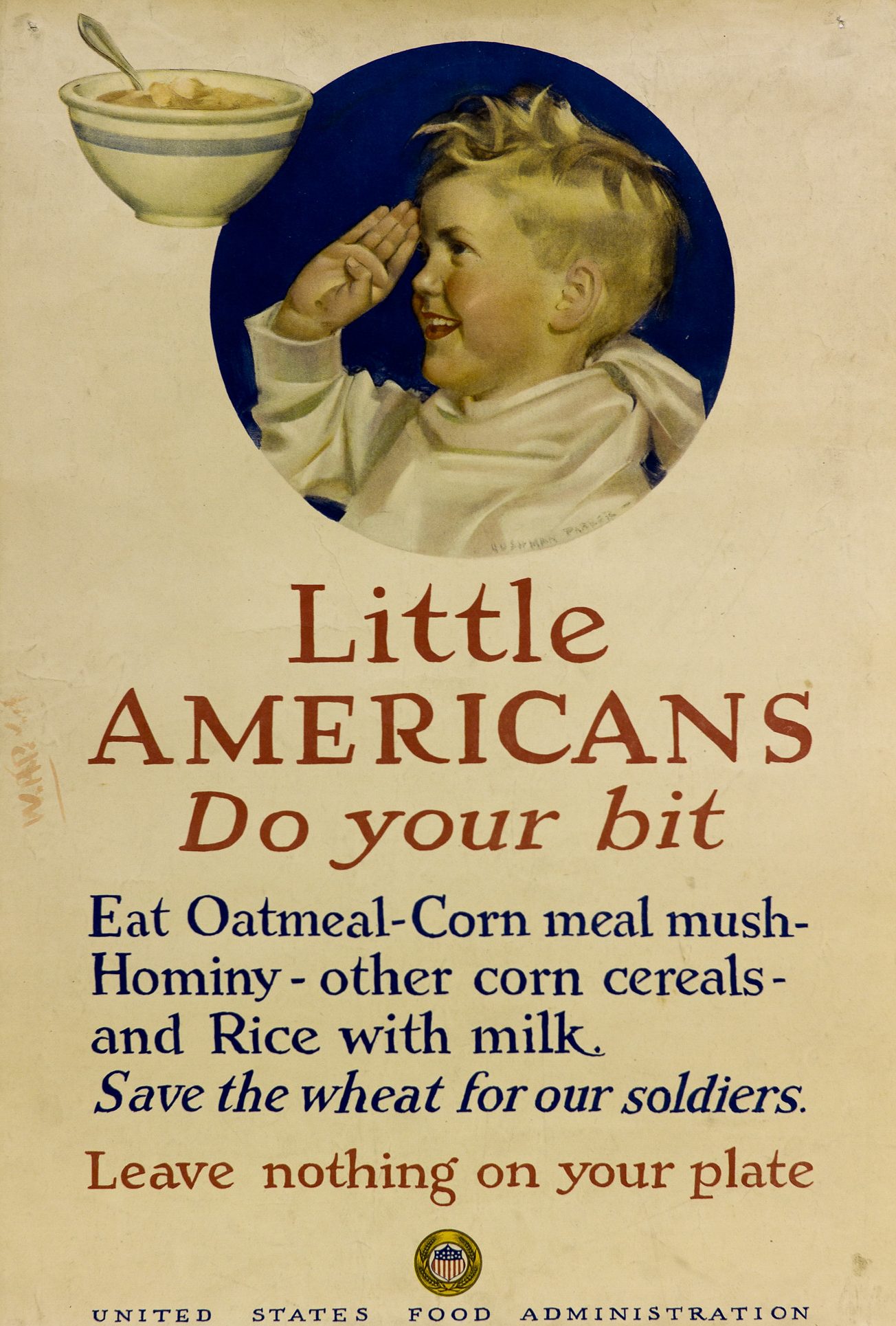

In an American World War I poster, a boy gives a salute, enthusiastically eyeing a dish in front of him. He fulfilled his civil duty and picked corn mush over a sandwich, saving a bit of wheat for soldiers on the frontlines. During World War II, Doctor Carrot — a character from the 1940s UK comics — and his friends urged children to eat more carrots. They said carrots were essential for night sight, which helped identify saboteurs more effectively.

WWI-era poster: “Little Americans, do your bit. Eat Oatmeal-Corn meal mush-Hominy — other cereals and Rice with milk.” Save the wheat for our soldiers. Leave nothing on your plate.” Image: Archives of Ontario

After both world wars, thousands of food-related posters, photos, and videos were left. Primarily, they show how exactly people changed their food habits. After all, millions of mobilized soldiers had to be fed. The home front had to cut back on wheat, mean, and sugar consumption for the military to maintain the mandatory 5,000 kcal intake. Also, civilians had to see about getting or, better yet, growing the substitutes themselves.

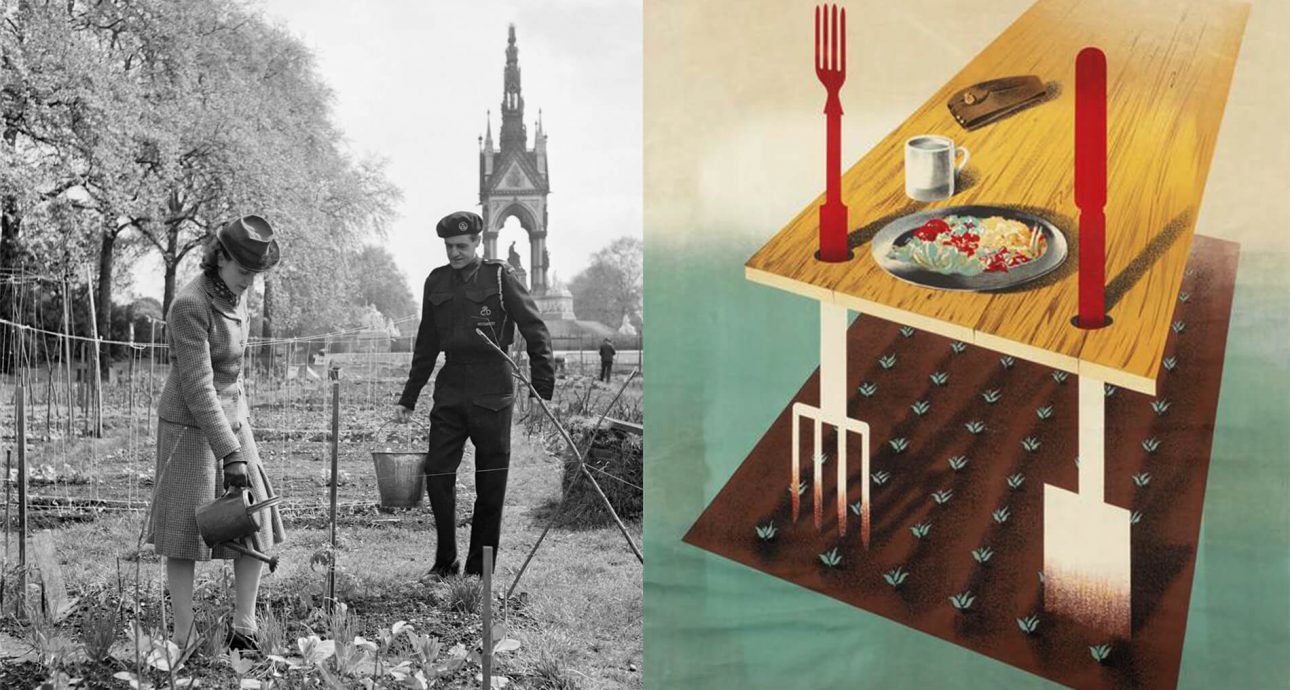

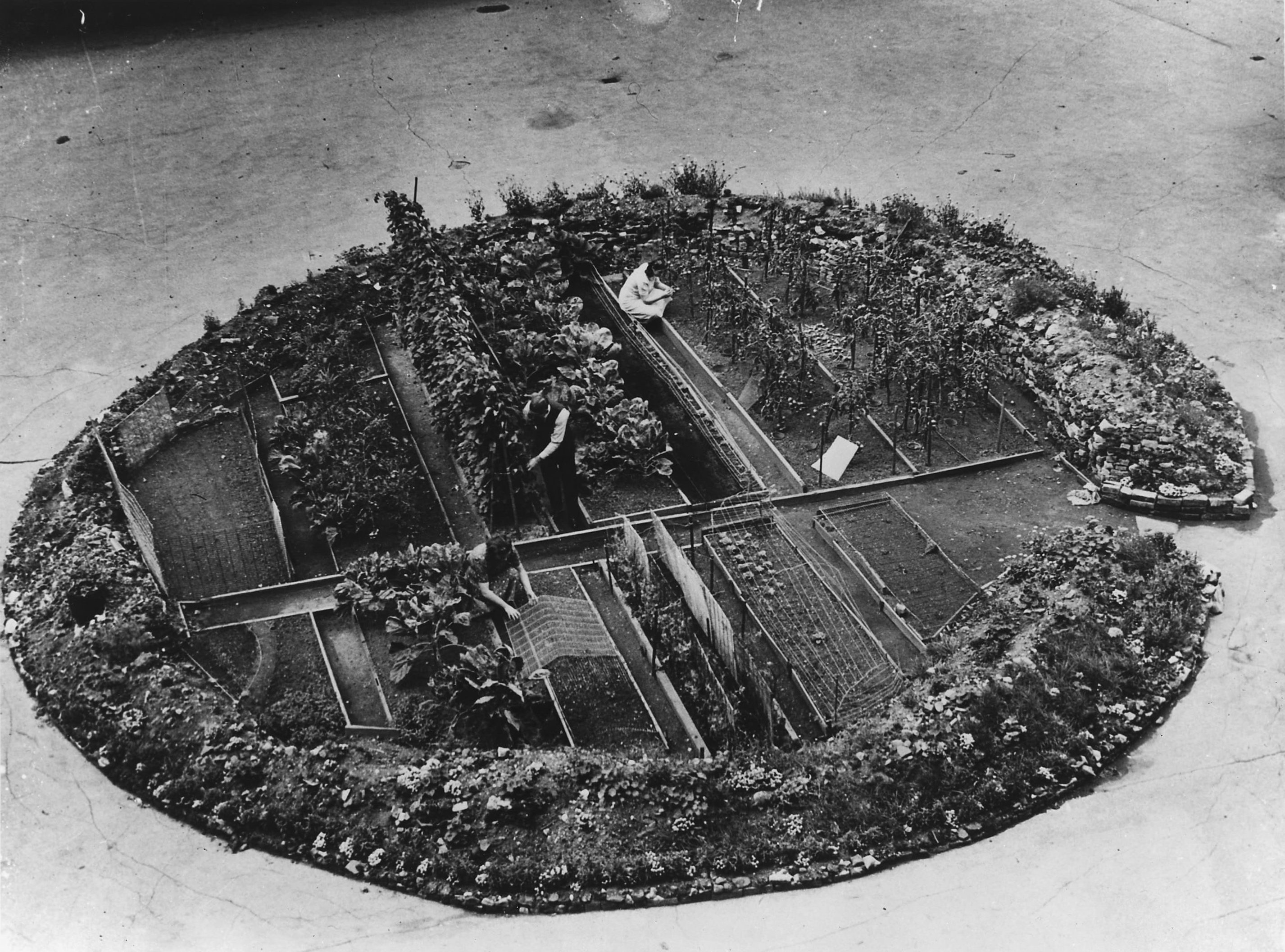

The photo of London half-ruined by incessant bombing shows the people working in a cabbage patch right in the shell crater. The smiling and vigorous housewives in the posters of that time urged to “can all you can”.

A garden planted in a shell crater. London, 1943. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ukraine faces similar challenges nowadays. The temporarily occupied territories, mined fields, lack of fuel, destroyed food warehouses, and changes in supply chains all threaten domestic and global food security. Like a hundred years ago, Ukrainians are recommended to plant “victory gardens” and consume food rationally. Also, people work together at volunteer kitchens, hold Ukrainian lunches all over the world, bake Chornobaivka bread, and prepare the dry Kolomya borscht for defenders. Let’s take a closer look at the “gastronomy front” as it was and is now.

Carrots for ice cream and Meatless Tuesdays

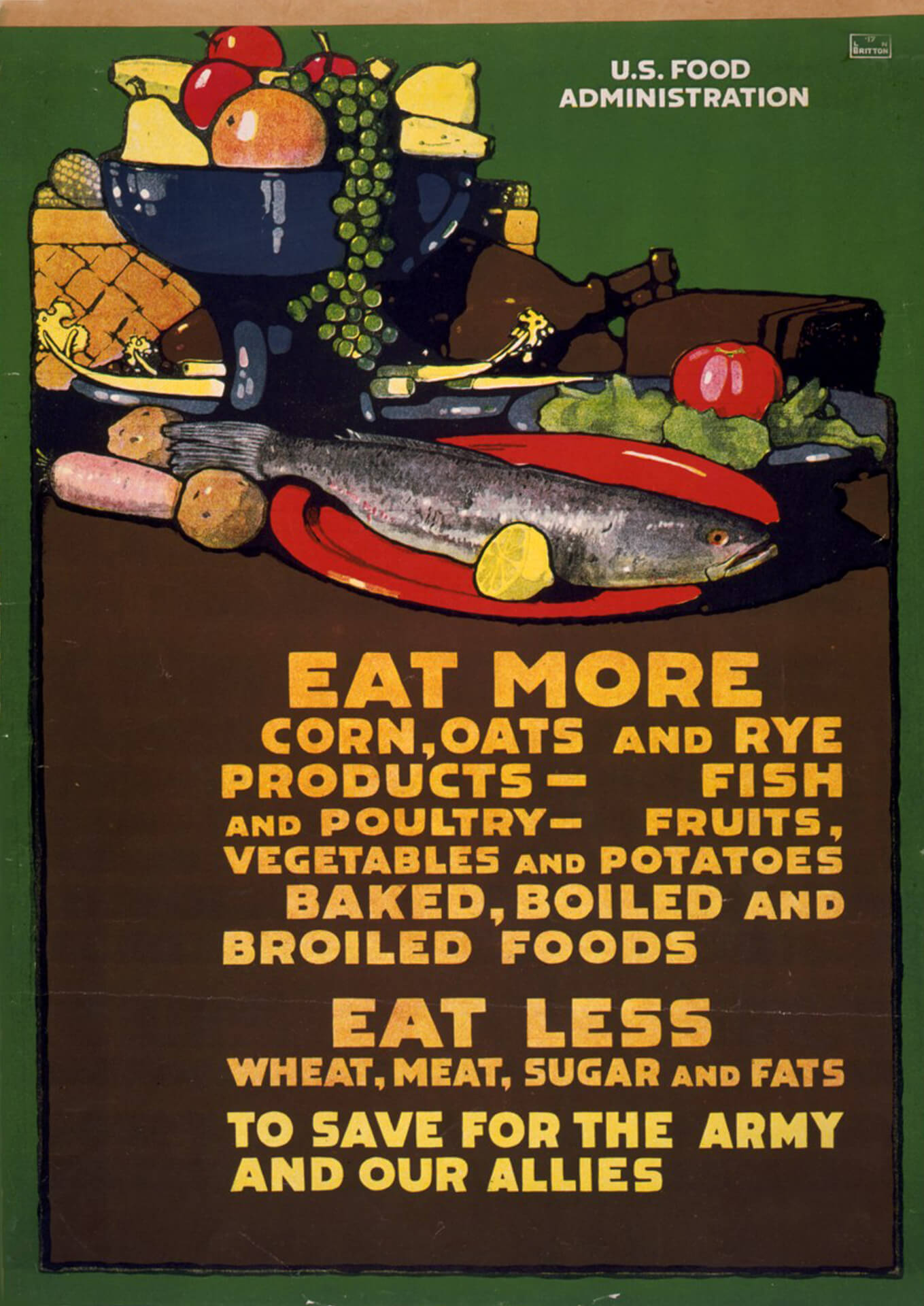

The USA entered World War I in April 1917. As a result, the Americans had to drastically change their food habits to feed the army and support their allies. The responsibility for that was assumed by Herbert Hoover, the future president of the USA and Director of the United States Food Administration at the time. The organization made over 1,500 posters and countless brochures explaining what to eat and how to American families.

As a result, half of the American families changed their consumption habits over the first six months of the war. The campaign was successful because it didn’t call on people to fast or consume unsavoury things but urged them to switch to a more diverse diet and eat more consciously.

The number one priority was just to cut the amount of wasted food. The most common slogans at the time were “Food is a weapon. Don’t waste it! Buy wisely — Cook carefully — Eat it all”, “Be patriotic. Sign your country’s pledge to save the food”, and “Sir — don’t waste while your wife saves. Adopt the doctrine of clean plate — do your share”.

WWI-era poster: “Eat more corn, oats and rye products; fish and poultry; fruits, vegetables, and potatoes; baked, boiled and broiled foods. Eat less meat, wheat, sugar, and fats to save for the army and our allies”. Image: US National Archive

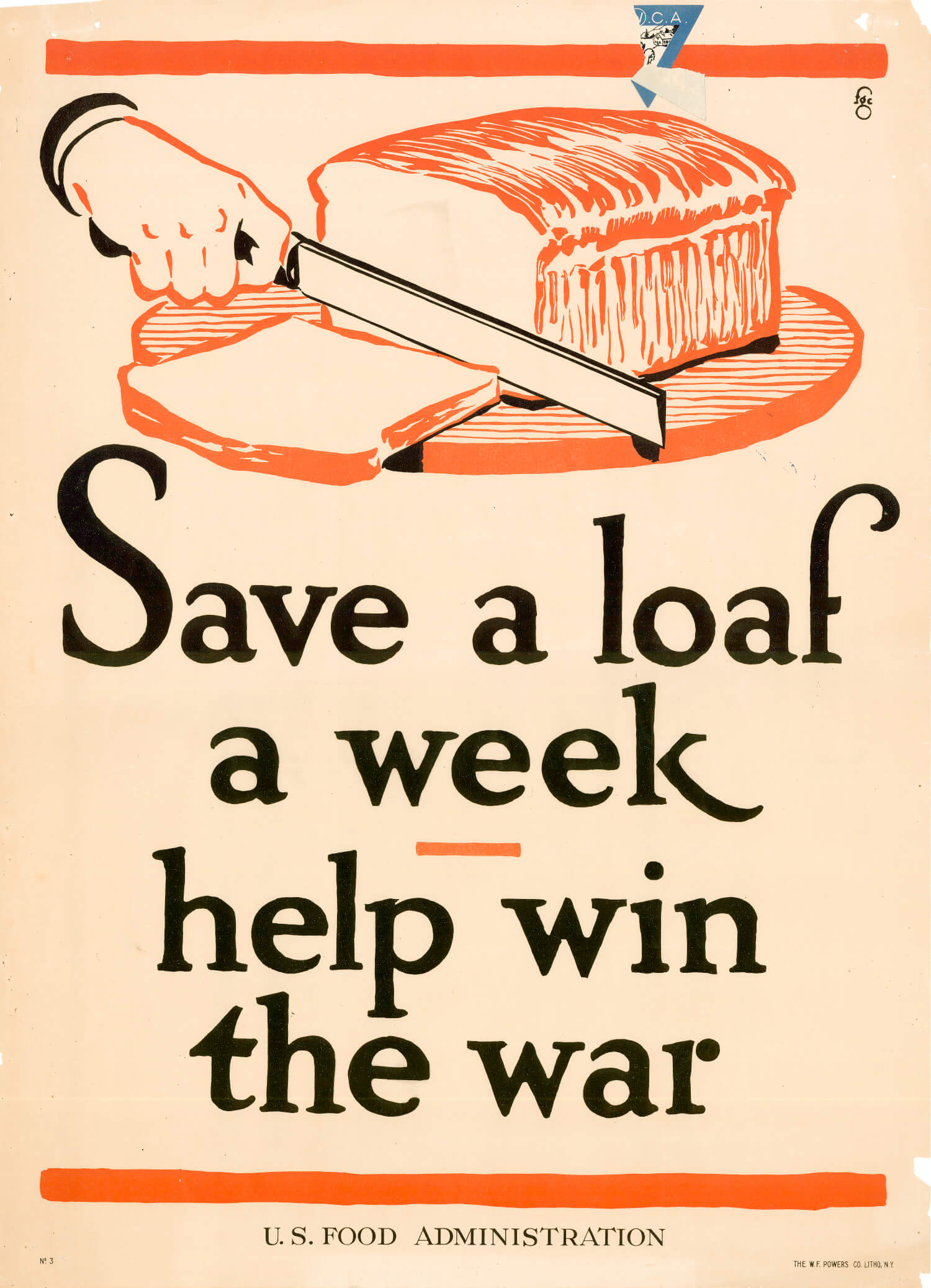

WWI-era poster: “Save a loaf a week — help win the war”. Image: University of North Texas Libraries

Making people consume less wheat flour, meat, and sugar, was more challenging. It took launching a campaign to promote the consumption of substitute foods: corn and potato flour, fish, and various syrups. In particular, the Americans were told that corn was “the food of the nation” and advised to use corn flour, corn starch, corn syrup, or corn oil in everyday cooking.

An advertising campaign for substitute foods was launched to make people consume less wheat flour, meat, and sugar. The Americans were told that corn was “the food of the nation”.

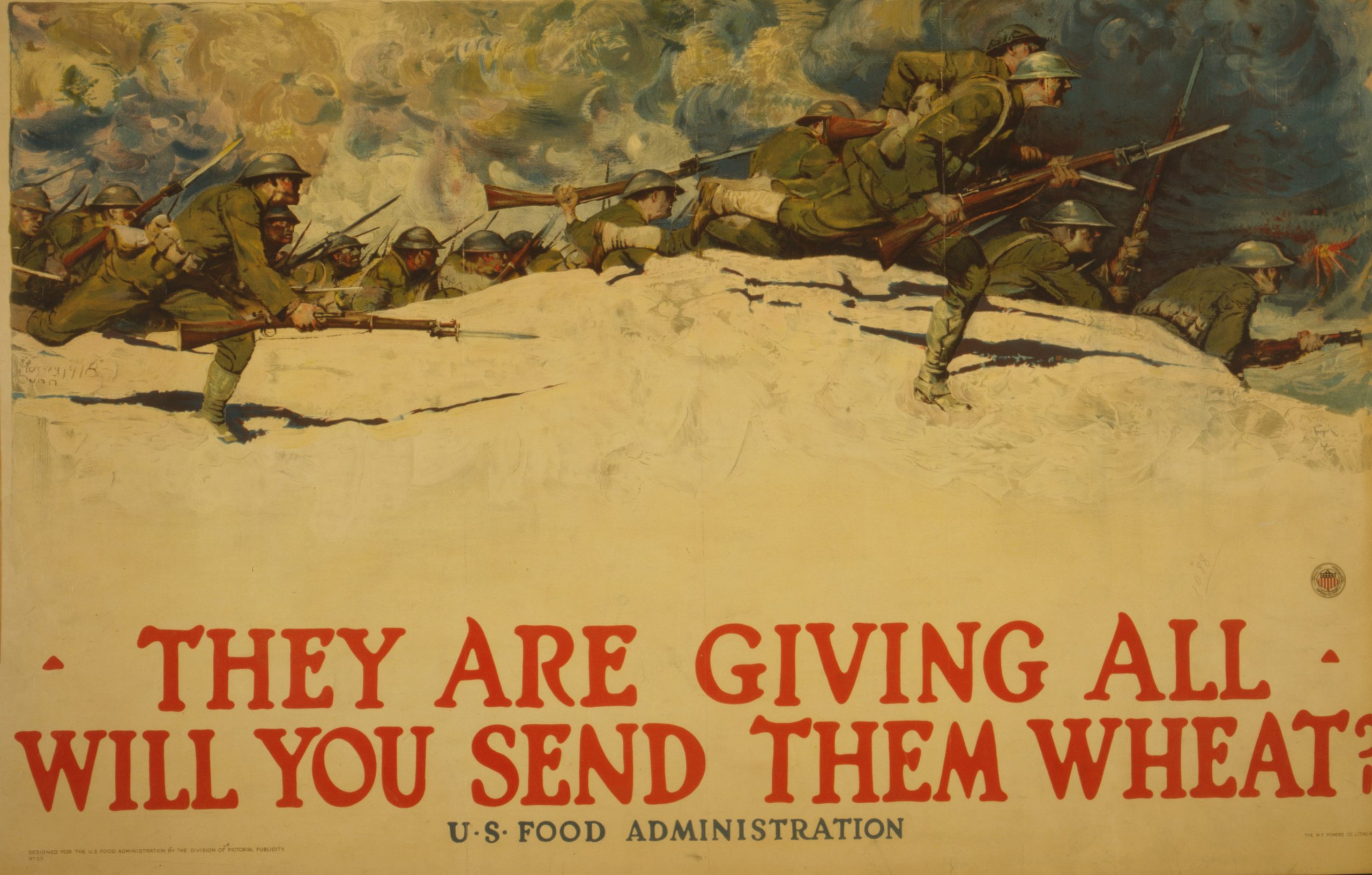

As the war went on, the rhetoric became tougher. A famous 1918 poster depicted soldiers charging into battle and a slogan: “They are giving all. Will you send them wheat?”

In addition, nationwide actions took place, during which people were recommended to refrain from eating specific products on certain days. The Meatless Tuesdays were the most common, but there was also a schedule for the entire week: Mondays and Wednesdays were wheat-flour-free days, and Saturdays were no-pork/bacon days. You could even play a “food bingo”, refraining from meat, wheat, or sugar for one or multiple meals per day to get at least nine for the week.

WWI-era poster: “They are giving all. Will you send them wheat?” Image: Library of Congress

Curiously, influencers started promoting Meatless Mondays in the 2000s. Although inspired by the World War I initiatives, they had a different goal — making the people’s everyday diet more healthy and balanced.

Besides imposing limitations during the war, the American government tried to suggest alternatives. Magazines and culinary books recommended baking “victory bread and pastry”, which had four-fifths of wheat flour and one-fifth of substitutes, e.g., oats. The potato bread “helped win the war”, too. In fact, it was considered a superfood because it was healthier, puffier, and tastier.

Alcazar cake was especially popular with housewives — it was made from potato flour and almond. “Victory muffins” were made from bran and wheat four and cannoli — from almond paste. It was recommended to replace sugar with treacle, honey, maple syrup, raisins, fruits, and chocolate while making pastry.

WWI-era banner: “Save food — 120 million allies must eat”. Image: US National Archive

WWI-era bread. Image: US National Archive

As a result of the campaign, the Americans halved their consumption of essential foods. Also, the USA increased the amount of wheat, sugar, and meat dispatched to ally countries by 15%.

The measures taken during World War II were more drastic. The countries went beyond recommendations, introducing food stamps. As early as 1939, Great Britain started preparing for the potential isolation from the international trade to rely exclusively on domestic resources. Although it didn’t happen, the situation was tense for a long time. Bacon, butter, and sugar rationing were introduced first in the early 1940s. Soon, meat, tea, jam, biscuits, cheese, eggs, and canned fruits were added to the list. The foods were distributed to local stores, where designated people could exchange their stamps for some amount of them. Even children were taught to use food stamps. Some instructional photos and videos for children showing how to buy sweets have even been preserved.

However, sometimes signs “No ices, buy yummy carrots” appeared in the shop windows. Carrots were put on sticks and given to children instead of ice cream. An entire campaign was even launched to make the relatively freely available vegetables — carrots and potatoes — popular among children.

However, sometimes signs “No ices, buy yummy carrots” appeared in front of the shops. Carrots were put on sticks and given to children instead of ice cream.

Thus, Potato Pete and Doctor Carrot came to be. The characters were put in posters, books, and educational videos. In one case, Doctor Carrot said that carrots improved sight so much that they made it easier to see in the dark, which was especially important during blackouts and while looking for saboteurs in the city at night.

Ukraine has not resorted to adjusting its people’s food habits yet. Still, the humanitarian crisis is already felt in some cities and towns in the temporarily occupied territories and the zone of hostilities. Therefore, bloggers and influencers have started communicating about it themselves. Chefs create dishes from the simplest foods and encourage people to cook them. Meanwhile, journalists share tips on the economic consumption of foods and rational stockpiling.

Some of the latest recipes you can find on the Instagram page of chef Marco Cervetti are: «stale baguette breakfast» (a good way not to waste bread), Swiss hash browns (require potatoes and butter only), apple sweets, sides that need no cooking (relevant for the cities with frequent electricity outages and meat shortages). Also, he advises people to stockpile long shelf life foods: flour, groats, beans, canned foods, and tomato paste.

The content on Ievgen Klopotenko’s website also changed after the war broke out. Most recipes rely on simple and widely accessible foods with a long shelf life. Also, there are many tips on baking bread and homemade pastry. Among the most popular are varenyky filled with canned beans, homemade stewed meat, oat bread, and definitely palianytsia — the bread that has become a gastronomic symbol of the Ukrainian national resistance.

Victory gardens 100 ago and now

The “victory gardens” have been one of the first food-related ideas to gain traction in Ukraine. People are already sharing pictures of their vegetable gardens on their houses’ grounds, balconies, and windowsills.

The first “victory gardens” were planted in the USA in 1917. The idea was to involve city dwellers in agricultural production, converting parks into vegetable gardens and planting foodstuffs in flowerbeds during the crisis.

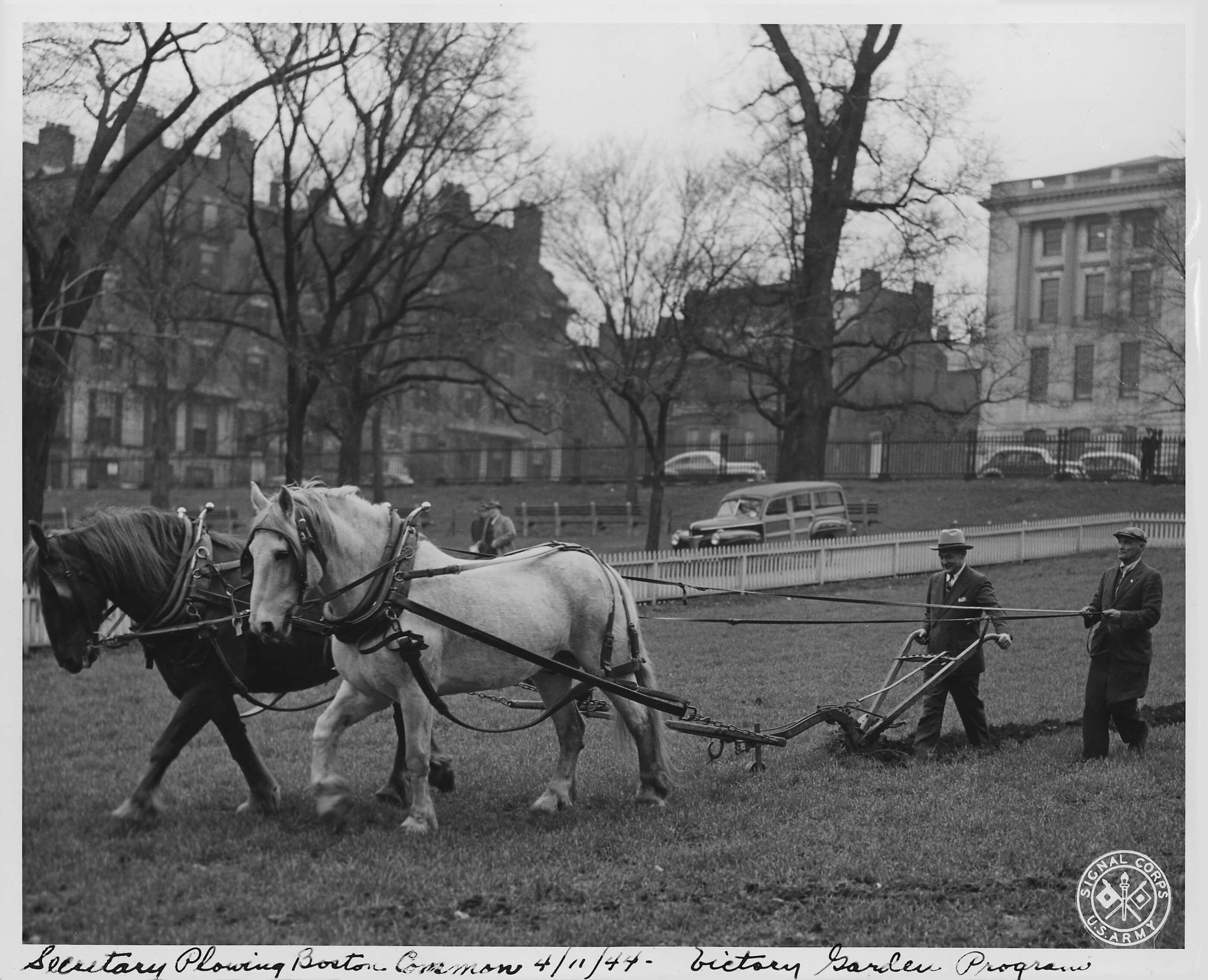

Secretaries are ploughing a public space in Boston under the Victory Gardens programme, 1943. Image: Wikimedia Commons

One of the public victory gardens in the USA, 1943. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The results were staggering. Five million vegetable and fruit gardens were additionally planted in the country, and they produced $1.2 billion worth of foodstuffs. During World War II, 12 million Americans grew enough fruits and vegetables in their victory gardens to cover their commercial turnover in the USA.

Similar programmes were also introduced in other countries: Great Britain, Canada, and even Australia. Numerous posters with the slogans “Dig on for victory”, “Sow the seeds of victory”, etc., were printed to promote the idea. The War Garden Parade short film shows a triumphant parade of people with carts full of produce they grew themselves instead of soldiers, guns, and tanks.

During World War II, 12 million Americans grew enough fruits and vegetables in their victory gardens to cover their commercial turnover in the USA.

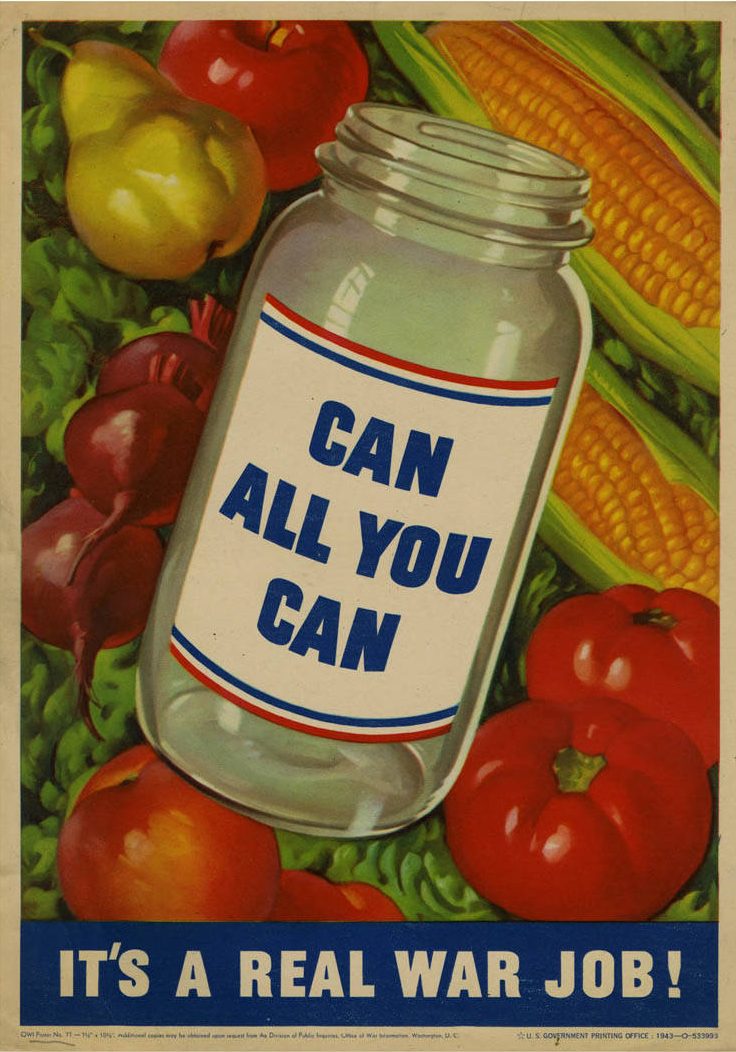

Numerous gardening masterclasses were held for housewives and children. To spread the word about the movement, a part of London’s Hyde Park, New York’s Riverside Drive, and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park were cultivated in the 1940s. Eleonora Roosevelt even planted a vegetable garden herself in front of the White House. The next step was a call for people to ensure long-term storage of the vegetables and fruits the people grew, which gave birth to the slogan “Can all you can”.

Researchers point out that vegetable gardens boosted civilians’ morale in addition to tackling the food crisis. People on the home front felt they also contributed to the victory as they harvested what they had grown, talked while working in the community gardens, and sent canned foods to the front.

WWII-era poster: “Plant a victory garden. Our food is fighting. A garden will make your rations go further.” 1943. Image: Wikimedia Commons

“Can all you can” poster, 1943. Image: Tennessee State Library and Archives

In Ukraine, the «Victory Gardens» national programme was launched back in March, as experts believed the country could lose up to 42% of crops, 68% of tomatoes, 71% of aubergines, and more because of hostilities this year.

The programme includes numerous seminars and masterclasses, e.g., Become a Farmer and Grow Your Own Borscht. Also, it involves providing all necessary seeds to communities. The Victory Gardens website has a calculator to count how much of which foodstuffs a family might need and how large a land plot it takes to grow them. Also, working in the victory gardens is seen as a means of integrating internally displaced persons into local communities, as manual labour and shared results are known to bring people closer together.

A victory garden in London, 1942. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Borscht, charity, and culinary diplomacy

There are also full-cycle projects in Ukraine, such as «Kolomyia Borscht», launched by Anna Yankovets from Kolomyia and Olesia Yarovska from Kyiv. They assembled a community of a few dozen women who donate ingredients, dry, crush, bag them and then make dry borschts and soups for the frontlines and sale. It has grown from a volunteer start-up to a full-fledged business project that provides jobs and helps displaced women in the city.

Private farms also need support — the assets of some were destroyed by hostilities, and others are short of fertilizers and animal foodstuffs. Multiple initiatives target such producers, including #theVictoryMenu. Ihor Mezentsev and the Ukrainian chef community have developed several Ukrainian cuisine recipes using many locally available foods. The Ukrainian restaurants that keep their doors open amid the war are advised to include these in their menus, support and promote local farmers, and hold thematic lunches to raise money for Ukraine’s humanitarian needs.

Many Ukrainian lunches and Ukrainian cuisine masterclasses held all over the world now have a charity aspect to them. Also, British food writer Olia Hercules launched the #CookForUkraine challenge, in which thousands of people are already participating. Restaurants and chefs worldwide serve borscht, hrechanyky, varenyky, and pampushkas and hold charity streams to raise money for Ukraine. The project has already raised over EUR 1 million, and Olia Hercules and food blogger Alisa Timoshkina got The Champions of Change Award for that.

Perhaps, every professional community in the gastronomy industry has launched a challenge to support Ukraine: #BrewForUkraine (brewers are offering special-edition beers GLORY 2 U, Common Enemy, Bayraktar Dry Stout, From San to Don), #BakeForUkraine (a bakers’ fundraiser launched by American pastry chef Paola Velez), #MakeDrinksNotWar (Italian barmen got an idea to make cocktails to support Ukraine), #DrinkersForUkraine, #FermentForUkraine, and more. They urge everyone to cook borscht, roast coffee, drink cocktails, make sauerkraut, and generally do anything to support Ukraine.

Brewers offer thematic beers: GLORY 2 U, Common Enemy, Bayraktar Dry Stout, and From San to Don.

The members of #ChefsForUkraine are raising several million dollars for World Central Kitchen — a non-profit founded by celebrity chef José Andrés, which has deployed a humanitarian mission in Ukraine and funds Ukrainian restaurants involved in volunteer efforts.

Ksenia Amber has become the first Ukrainian female chef to speak at Madrid Fusión, the world’s largest gastronomy congress. She spoke of Ukrainian restaurateurs’ volunteer kitchens and cooked green borscht with fish and mushrooms. Now Ksenia holds charity Ukrainian dinners in various European countries. Photo: Rodrigo Diaz

Ukrainian chefs are also making every effort to promote Ukrainian cuisine and raise money. Yurii Kovryzhenko, for instance, has held dozens of charity events in London already. Among them is Cook For Ukraine Supper Club at Jaime Oliver HQ and Lunch 4 Ukraine in Grosvenor House JW Marriott’s Great Hall, attended by a thousand people.

All this work is not in vain: Ukrainian cuisine is gaining prominence and traction. La Bourse et La Vie, a famous French restaurant, has recently changed its name to Le Borscht et La Vie. Until the 31st of May, it will serve carp in aspic, varenyky with potato and bacon crisps filling, honey cake, hrechanyky, and, naturally, borscht — all cooked by Ukrainian chefs.

New and best