Needle, Yoga, Chess: The Life of Nepal Drug Users in a Project by Sergei Stroitelev

Photographer from St. Petersburg. Worked for National Geographic Russia, Vokrug Sveta, Lenta.ru, Meduza, Nevskoye Vremya, LensWork, Wall Street International Magazine, Vice UK/USA, RIA Novosti, Kommersant, Getty Images. Received Jury’s Special Award at Humanity Photo Awards 2015, and awards at Young Photographers of Russia and Zolotoye Pero.

It rains when I arrive in Hetauda — the monsoon is in full swing. Every third male citizen here has an addiction — mostly, crack or heroin. You can’t tell between the slums and the downtown here: the same slaughterhouses, half-ruined houses, unfinished concrete constructions.

‘Sorry’

I check into the only hotel in town, into a room with a hook for a fan on the ceiling and wooden planks for a bed. In the morning, a knock on the door wakes me up: I am greeted by a woman from BIJAM, an organization that runs HIV and drug addiction related programs in town. Neelam, that’s the woman’s name, got a call from the hotel’s reception desk — they told her that a foreigner with a camera had arrived. She offers me a typical Asian barter: her help and information in exchange for my photographs. We agree that I come to the organization’s office tonight to meet an active drug user.

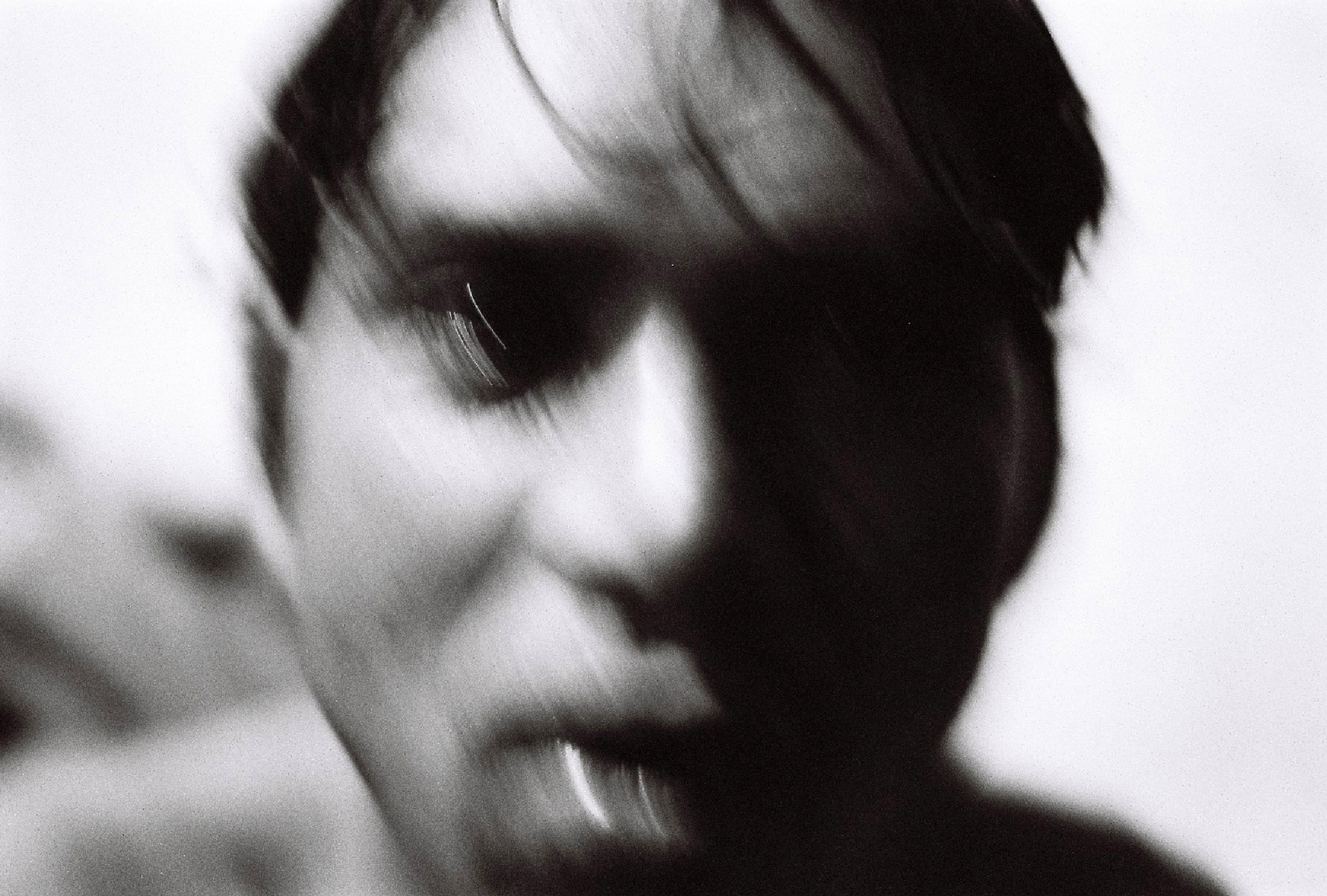

At night, a man of about thirty-five comes up to me, limping, gives me his hand and introduces himself as Babu. With the help of an interpreter, he tells me that he has been using drugs for 10 years — alternating between crack and heroin, which is rare in Hetauda. When I ask if I can take his photograph, he refuses and quickly leaves. However, when I go out to the street after talking with the employees of the organization, I meet Babu again: he changed his mind, and decided to invite me to his place.

On the way, he hums a jolly tune. As soon as we get inside, Babu sharply closes the door and grabs a metal rod; he swings it at me and demands that I give up my camera. When I explain that it’s a cheap film camera that he won’t be able to sell to anybody, the drug user scratches the back of his head, puts the rod down, smiles, and says: “Sorry.”

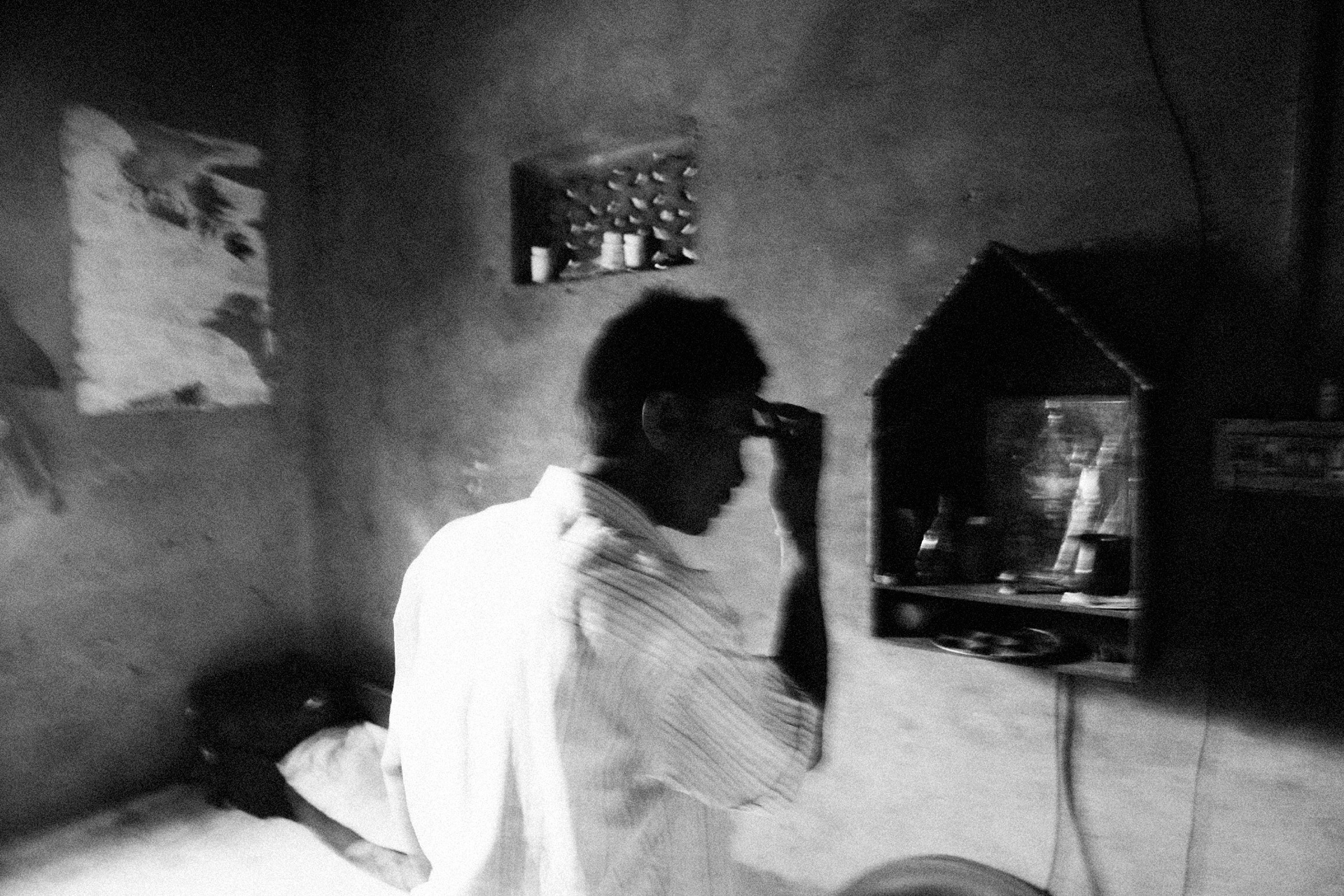

As we smoke and drink tea, I look around. The room has a light bulb, a bed, a leaky ceiling, and some posters. Under the bed, there is a spoon and a plate for drugs. Babu’s legs are rotting. He invites me to visit him at work tomorrow.

Chop for a Dose

The next day, we meet near the house, where his friends are already waiting for him. One of them is holding a package with white powder. Babu explains that it’s crack that they are going to smoke right now: it makes working easier.

In a stuffy 3×3 meter room, the man passes the crack around, while the new dose is being prepared on a tray. I hear tobacco crackle: when someone is high on crack, they usually want to smoke. The eyes of the users turn into bright dots, shining with excitement and the desire to do something. One of the men offers me a crack pipe.

The hype subsides, and everybody falls asleep for about forty minutes. We wake up from the sound of the rain on the roof, and head to a small slaughterhouse, where they сut bulls for local restaurants. If the guests saw these conditions, they would hardly eat there. Babu, who is still high, enthusiastically cuts meat with an ax, and his friend, who has a strong smell of alcohol on his breath and doesn’t wear any gloves, is busy with the insides.

After several hours of work one usually earns 10 dollars, but Babu receives 12: exactly as much as a crack dose costs. All the money goes for buying another smoke for the night. And every day is like that.

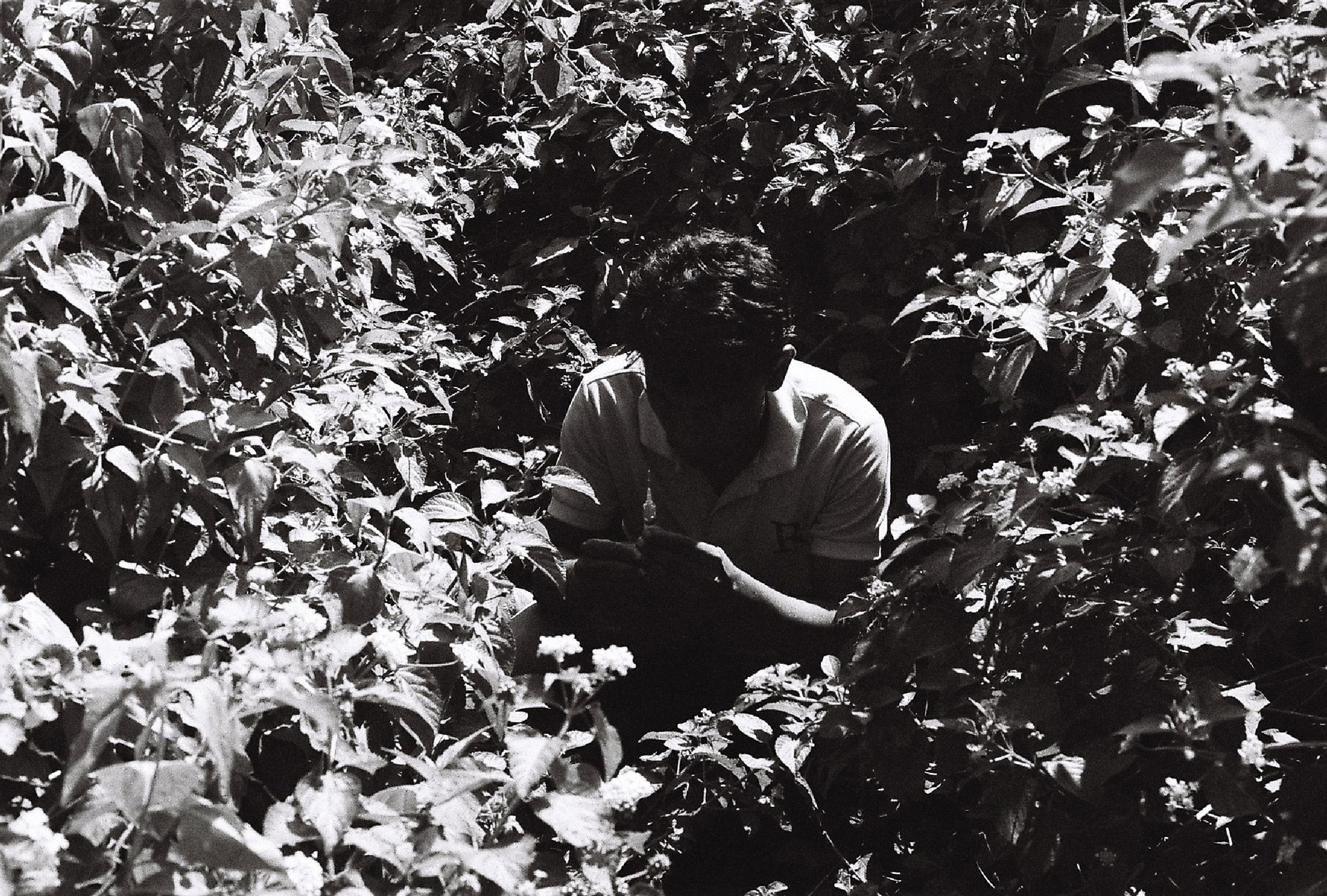

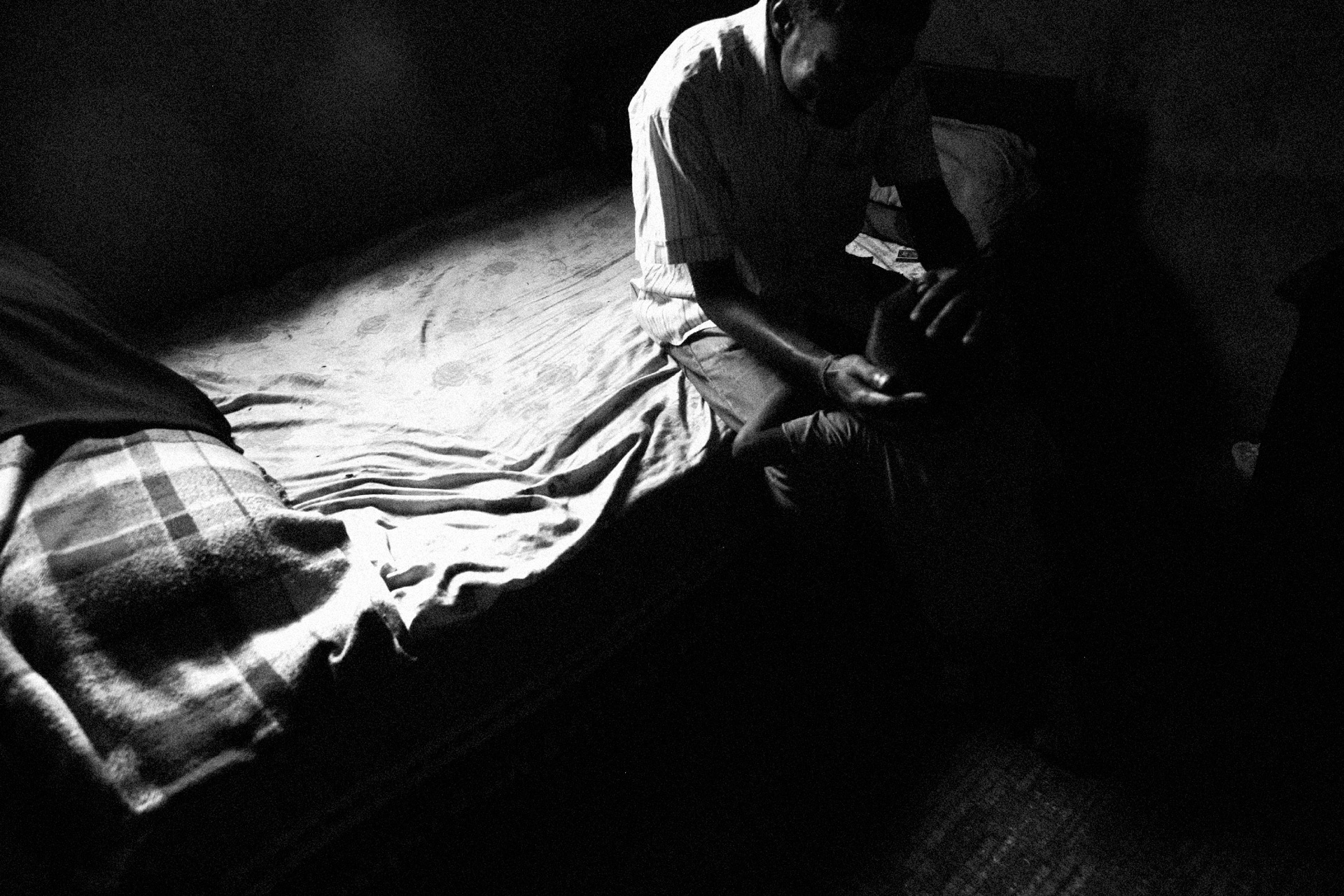

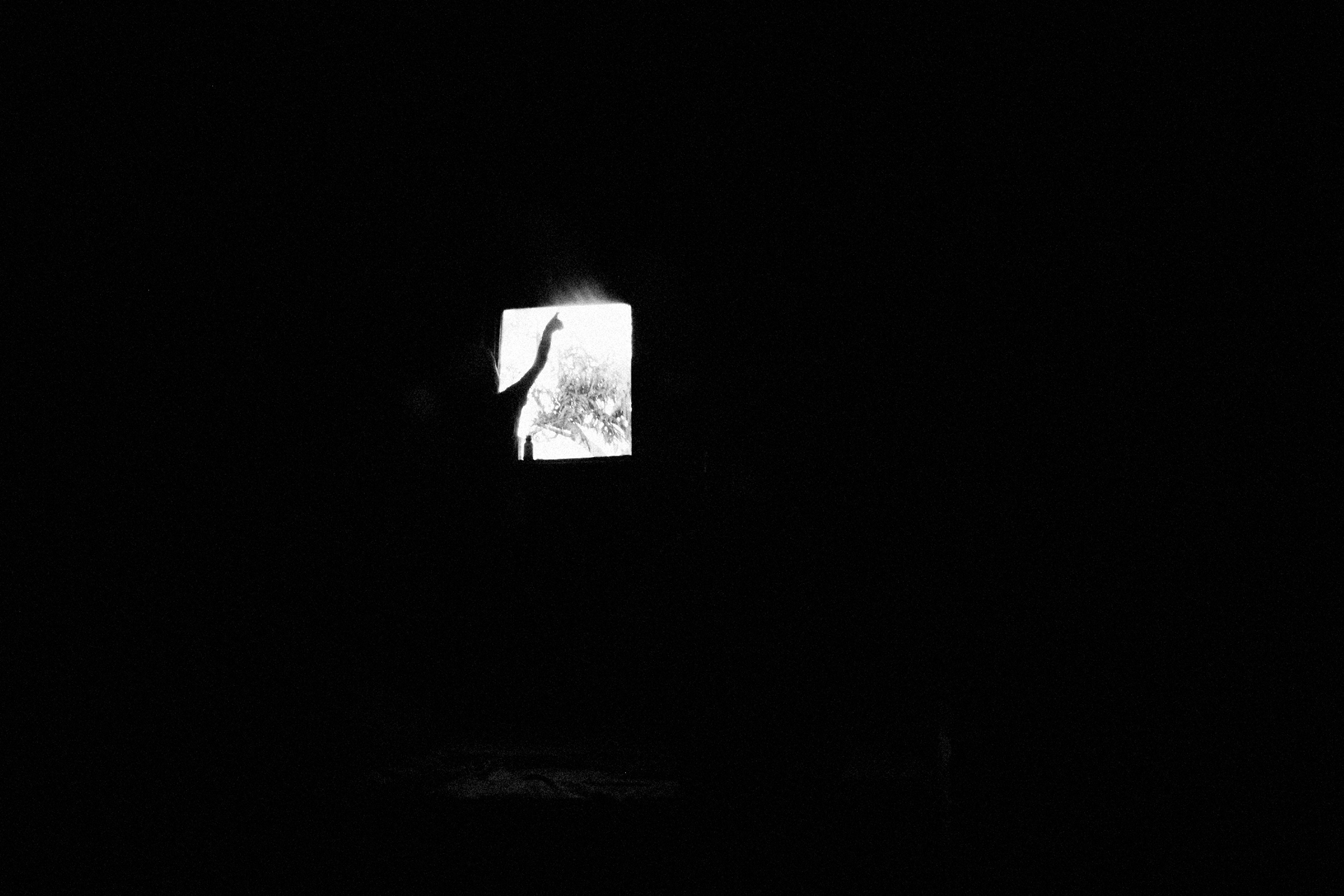

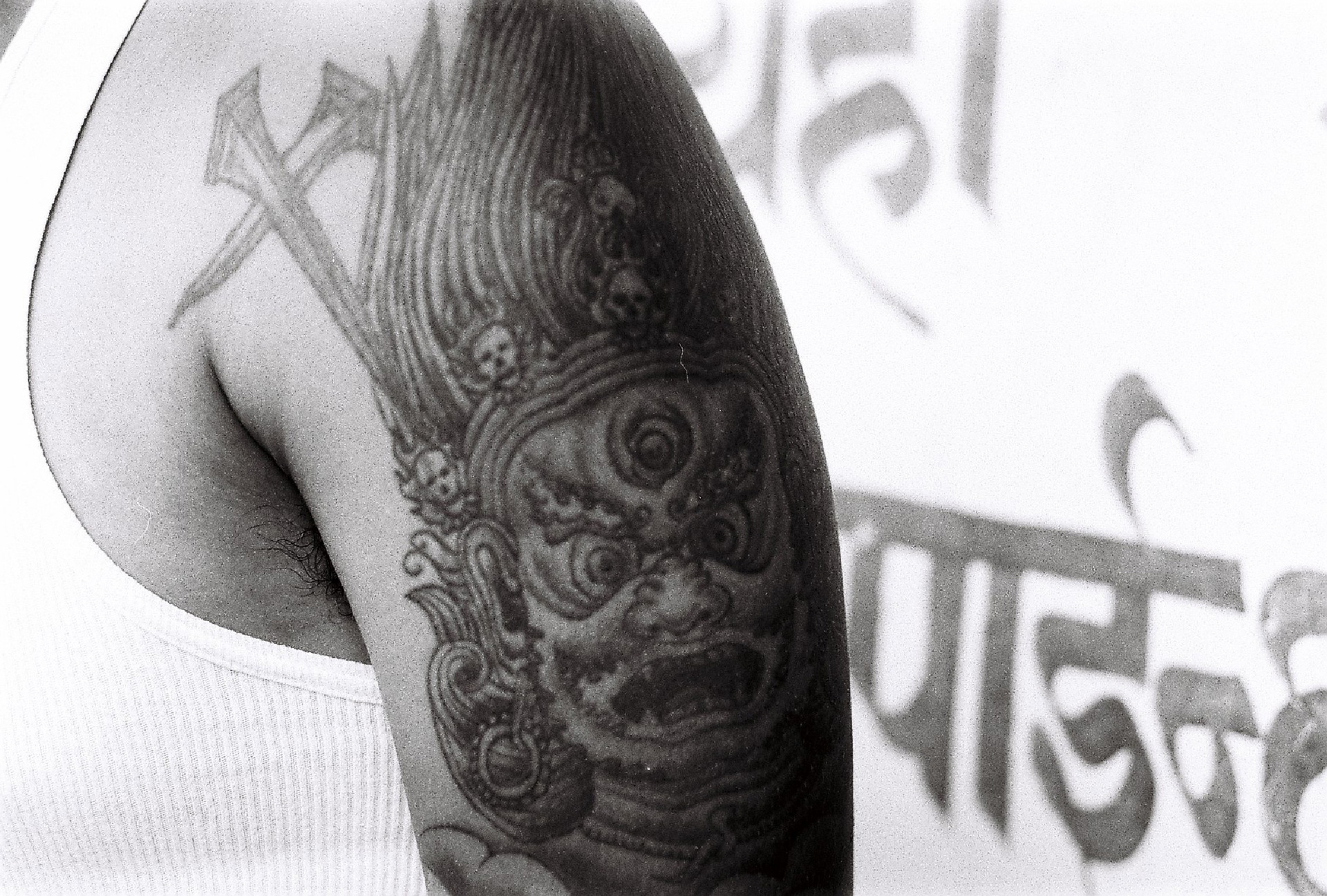

After meeting Babu, I started seeing the city in a different way. A man on the side of the road is anxiously waiting for his dealer: he says he wants to shoot it one last time, and after that he quits and becomes the king of the city. A man on a motorcycle stops by him, puts a package with heroin in his hand, and hurries away. The man runs into the bushes to shoot a dose. The next day, he will be lying back on the side of the same road, with the same hungry eyes.

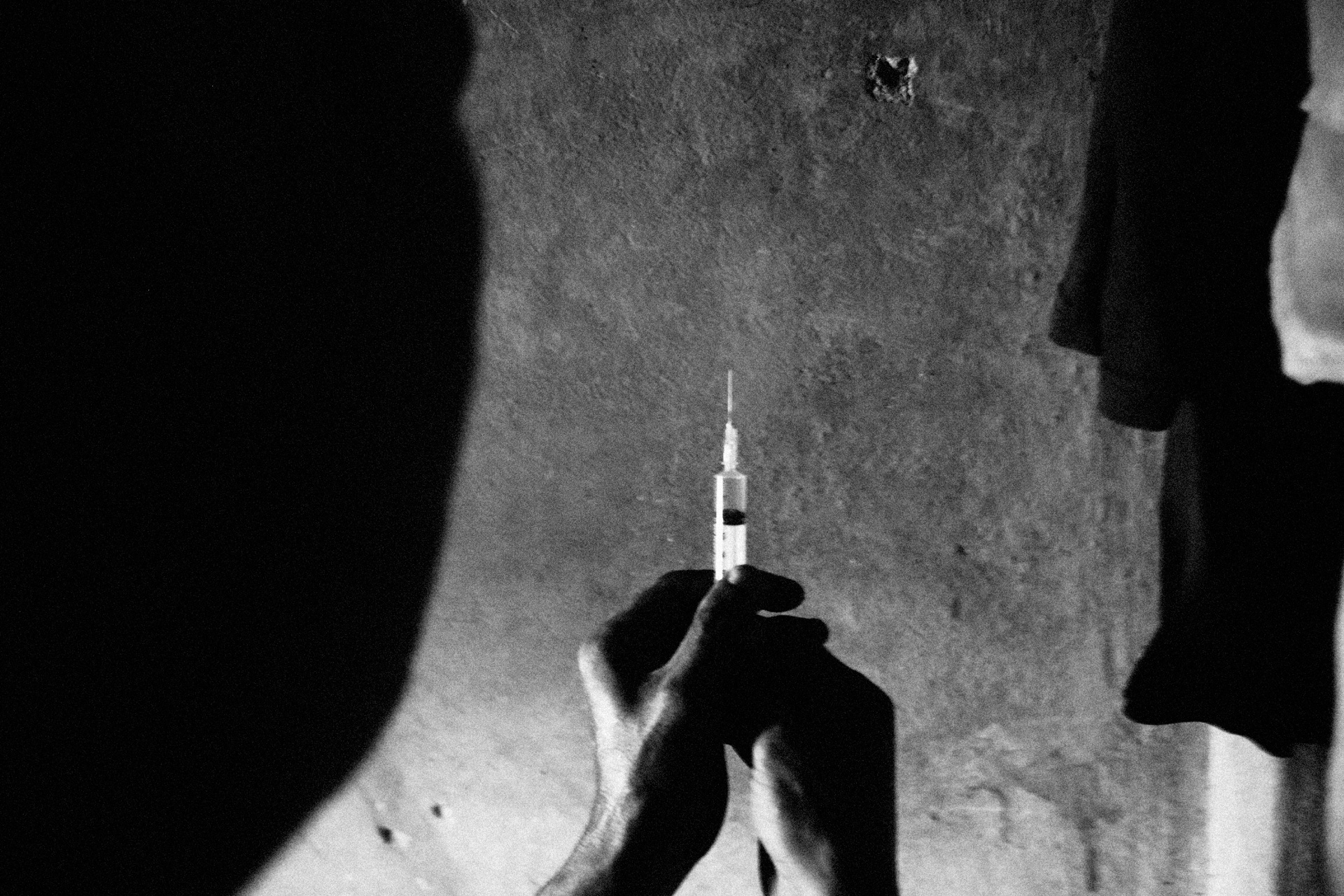

We walk on a dusty road to see another man. Kedar, skinny and with crazy eyes, who explains in broken English that he waited for me to shoot drugs. “You need to capture this — my tragedy and my happiness,” he says.

Without a word, he points to his wife and his six-year-old son at the door. For about 15 minutes, he plunges the blood with heroin from the syringe into the vein and back, extending the pleasure. Then he relaxes and lets his family back in. The woman silently cooks rice; Kedar’s father, who lives in the same room, comes for lunch.

Needle — Yoga — Needle

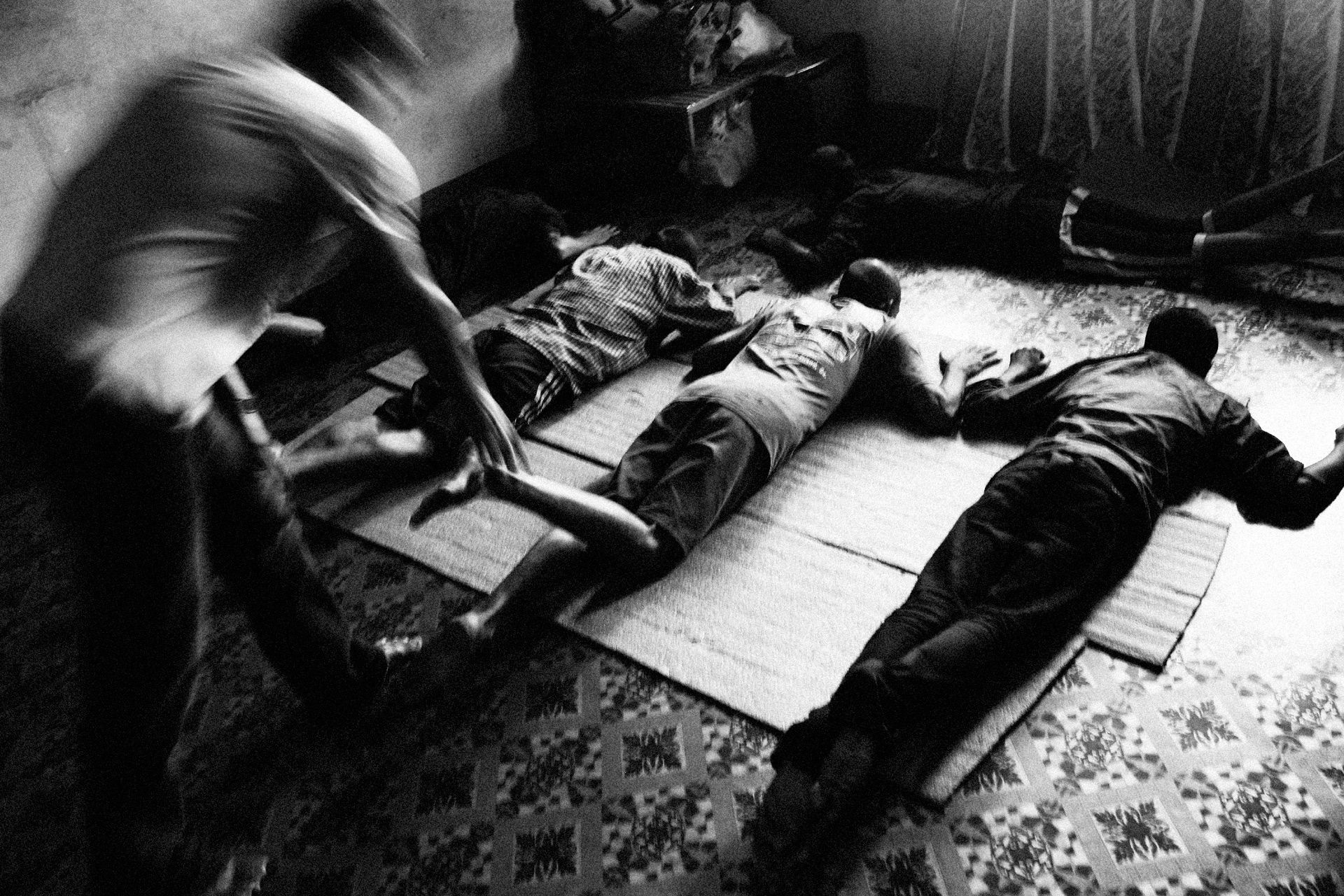

I visit an unofficial center that helps drug users, founded by a former addict. People come here for counseling and exercise therapy.

They are not very happy to see me. On the porch, Mohan, a thin, withered man, examines me head to toe, and asks multiple times where I come from and why I am interested in this topic. When I confess that I used to be a user myself, he relaxes.

Mohan tells me that he organizes a rehab on his own money, and got into debt. The center has big problems — the locals think it’s a den where they sell drugs. That’s why Mohan got stressed when he saw me with a camera.

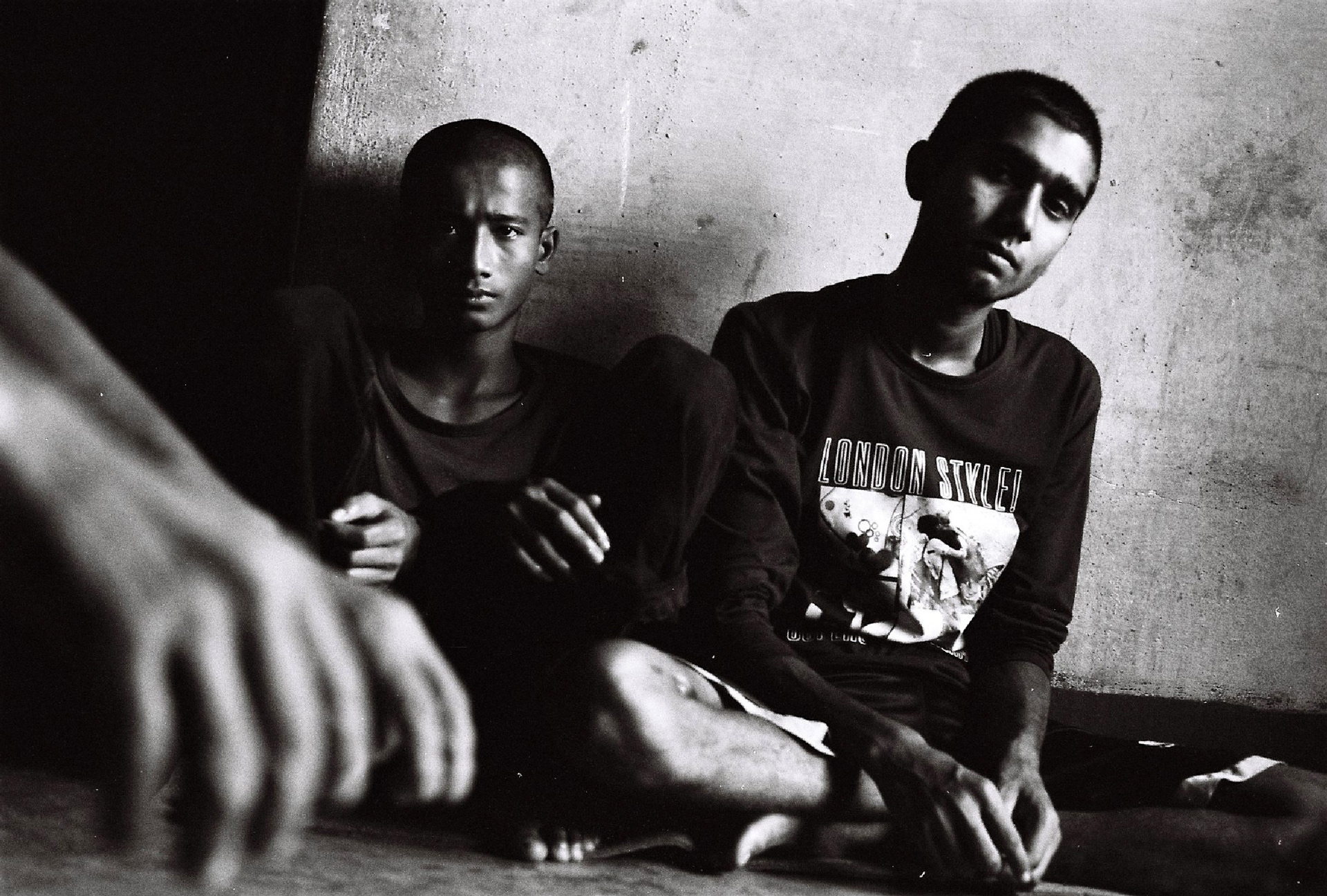

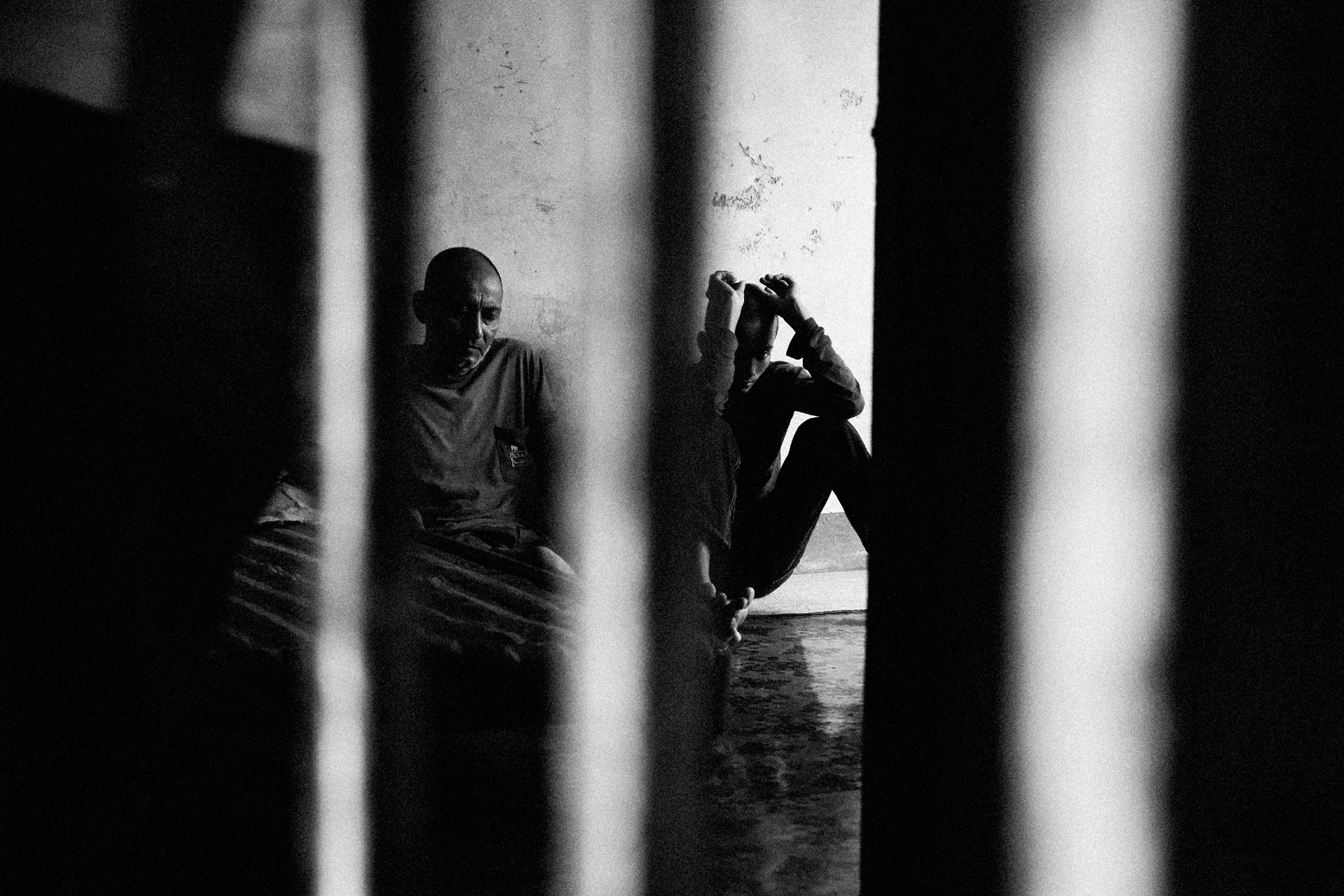

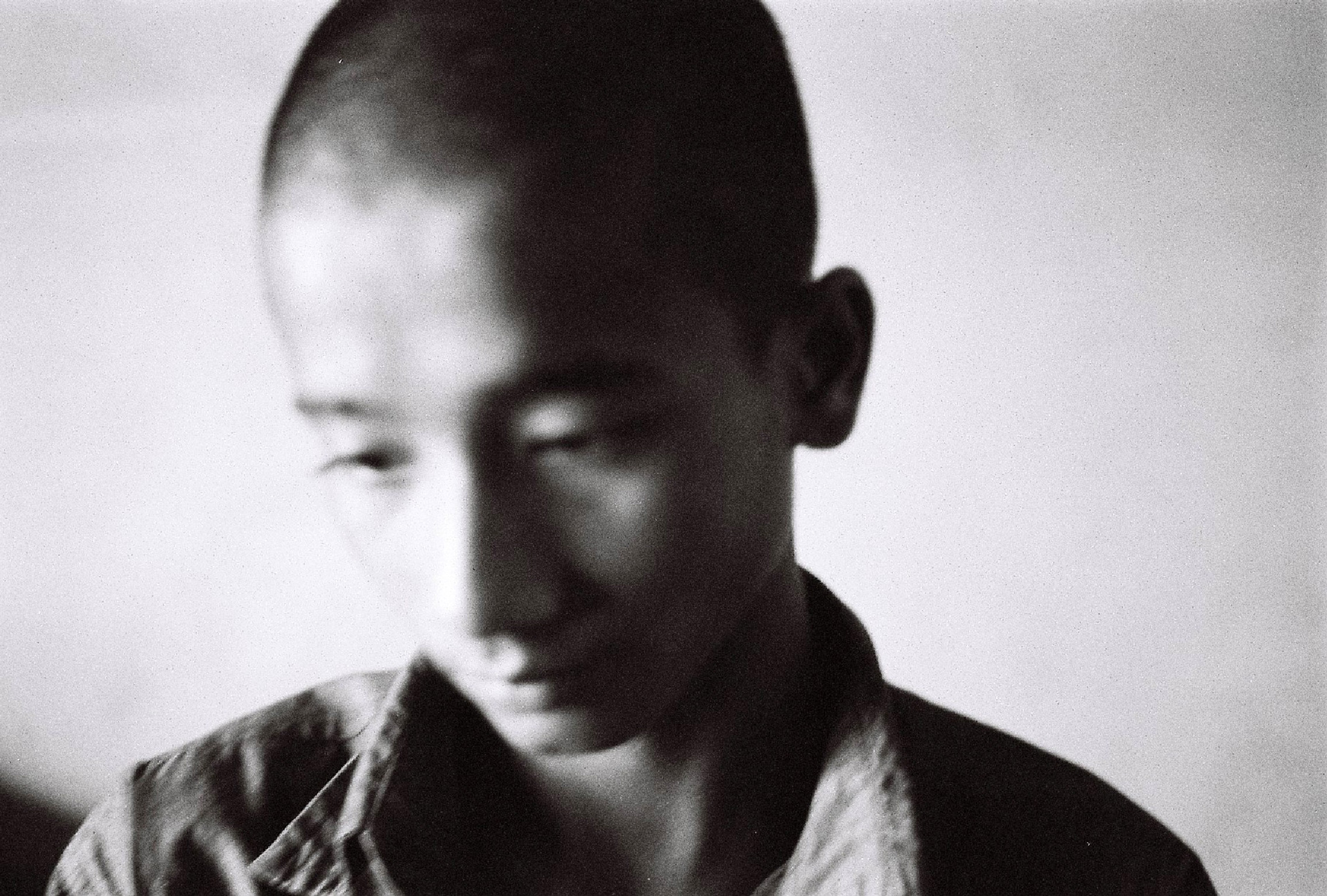

The interior is similar to a prison. There are many underage guys who were brought here by their addiction to smoking substances; some of the older teenagers are already on crack and heroin. Nobody here is sober, there is no light in their eyes. I see Kedar in the crowd.

I come in time to witness a yoga class; an instructor shows simple breathing exercises. There are also some board games and chess to help the addicts distract themselves from withdrawal at least a little. At the end of the day, Mohan gives an instructive talk about Buddhism and inner harmony. People are barely concentrating on what he is saying.

The center doesn’t take anybody in permanently: people come here for some time, and then go back to the streets. Mohan says that he manages to talk some of them out of the addiction. He criticizes BIJAM: he says that the only thing that the organization is doing is distributing clean syringes to the addicts, and this is not enough.

I think though that a cycle of ‘needle — yoga — chess — needle’ isn’t enough either, but it’s admittedly better than nothing.