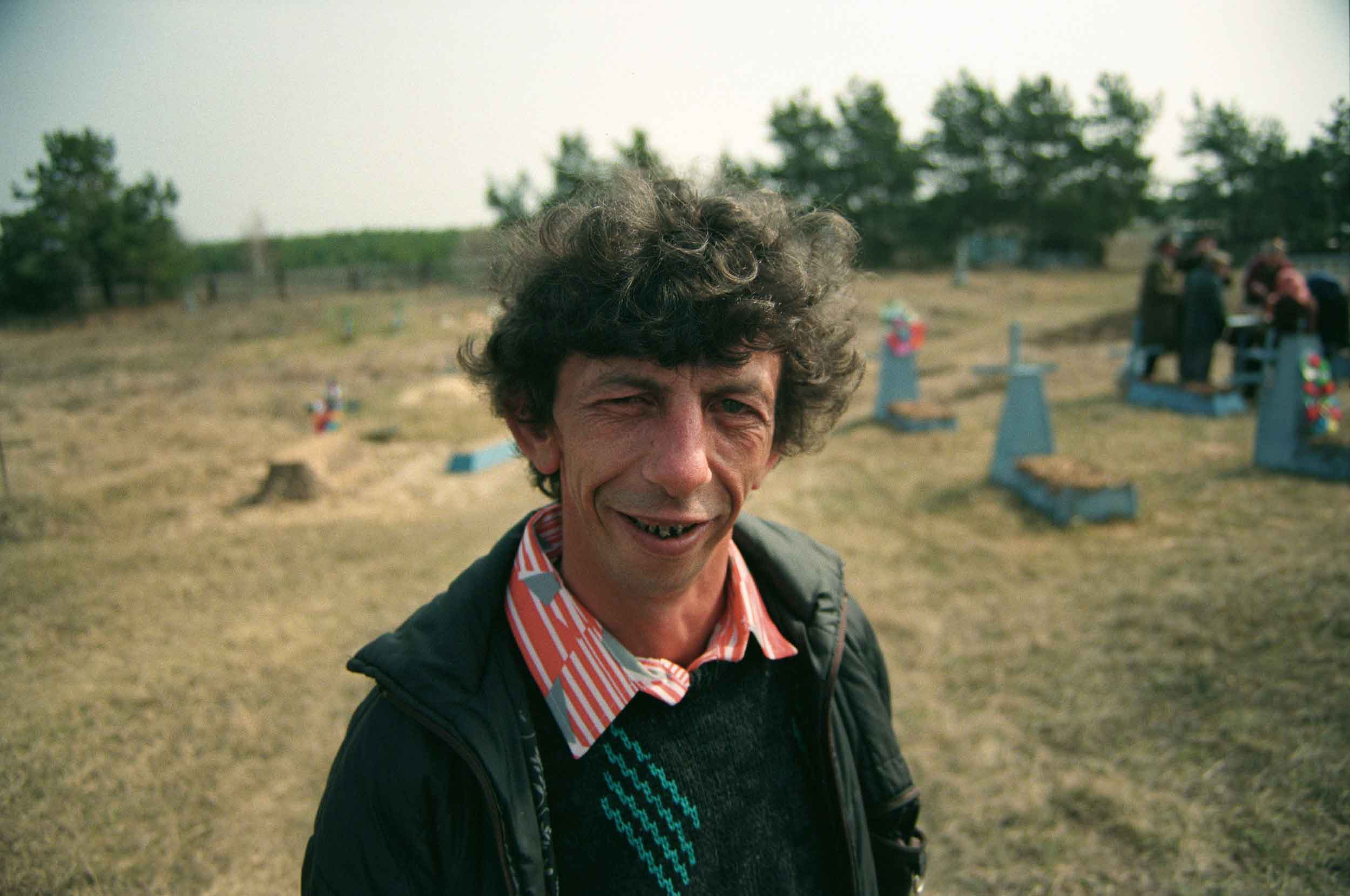

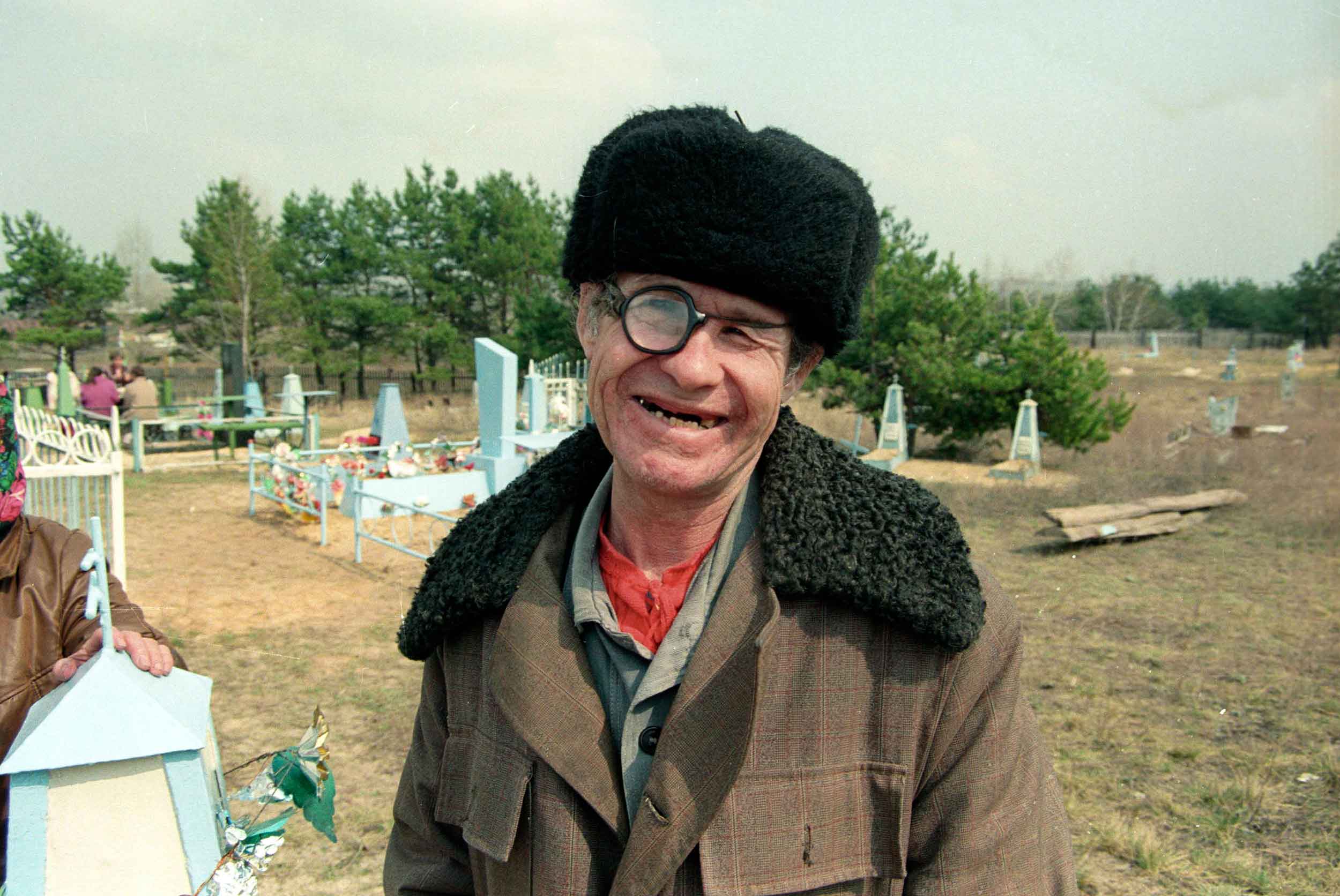

Donbass in the 1990s: That is How We Celebrated Easter in the Cemetery

My first memory of Easter is associated with something forbidden and the police. It was the 1970s in Luhansk, where I lived at the time. On the evening before Easter, the Peter and Paul Church in our district was surrounded by a police cordon. They stood in a tight circle and only let old people into the service. However, no one else was eager to get inside. As my parents explained to me, going to church was a personal matter and it was harmful.

My godfather said to me once, “I’m sorry, Sanya, when we baptized you, we didn’t go inside the church. Baba Vira, our neighbor, took you in her arms and brought you inside. That’s who baptized you.”

In the 1980s, I grew up and wanted to repent. The Perestroika was in full swing, and you could walk freely to the church, without police cordons, and weddings had become popular. While I was thinking about what to repent for, the priest hastened the procedure and asked, “Do you watch TV?” “Of course,” I replied, not understanding the essence of the question, and heard, “You’re already a sinner!” That was the end of my repentance.

To me, it seemed wild. Instead, it was natural to see bottles of vodka and tables with food at the cemetery on Easter, as it was customary in my hometown in the Donbas region. Everyone would greet each other, kiss and treat each other at the graves of their relatives. Some would drink until they were nearly dead to resurrect the next morning.

When I arrived in Kyiv, I decided to film at the cemetery on Easter, just like at home, and was surprised that no one showed up.

In the 2000s, priests on TV called for people to commemorate the dead during the week after Easter, known as “Chervona Hirka” or memorial week. People listened and started going to the cemetery on Easter and during the memorial week. There, at the cemetery, everyone met and continue to meet while still in this life.

Photo: Alexander Chekmenev.