Misha Pedan: “Taking and giving to others is the logic of working in the art world”

Ukrainian artistic photography owes a lot to Kharkiv, the exact place where a distinct “school” - a photographers’ union - popped up and shot Soviet reality in a manner that was then considered unusual. One of the participants of that union was Misha Pedan who took up photography by accident and left to live in Sweden right before the collapse of the USSR.

Today, Misha is a teacher at Kulturama, one of the leading Scandinavian art schools, the director of the “Spine” international photobook festival, and the founder of the Ukrainian Photography Alternative. In October 2015, his book M landed on the short list for The Anamorphosis Prize, where it will compete with books by Alex Webb, Caroline Drake and Shawn Lee.

Photographer from Kharkiv, has lived in Sweden since 1990. Founder and coordinator of the Ukrainian Photography Alternative (UPHA). Has taught at the Kulturama photography school in Stockholm for ten years. Director of the “Spine” photobook festival since 2015.

How did you take up photography?

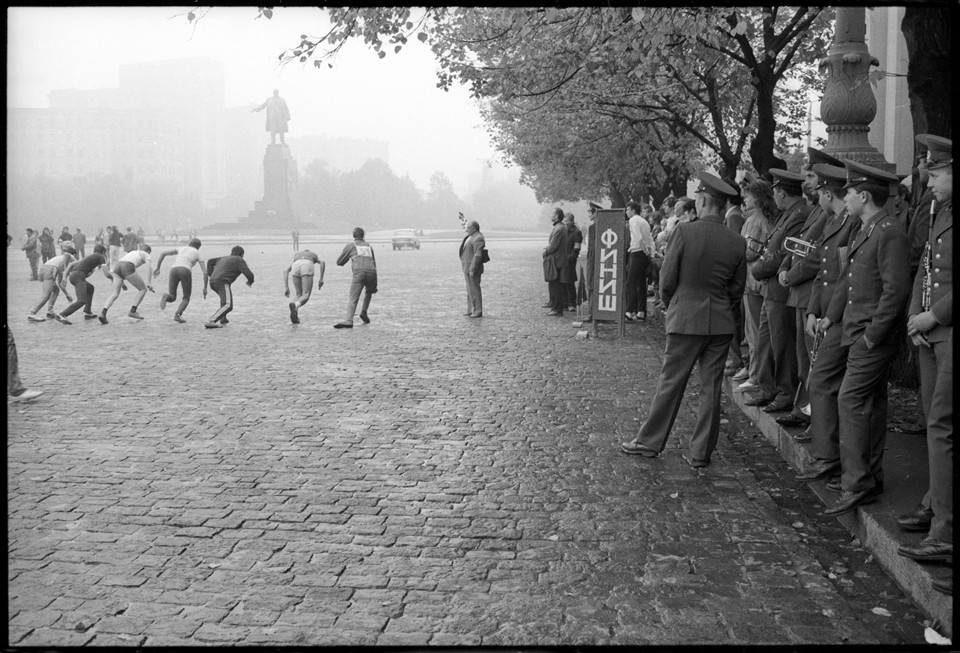

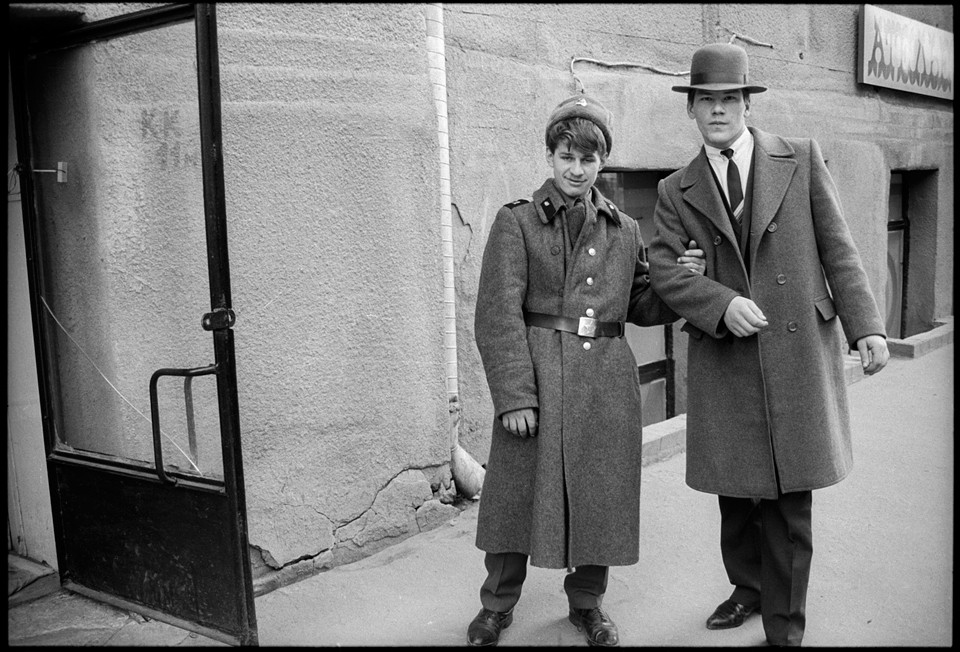

I started taking photos in the eighties while working as an art designer in the Kharkiv committee for sport. Some photographers shared a basement with me and we did some meaningless agitation together. Once, two of the three photographers were sick and I was given an offer to replace them. It turned out to be pretty easy and my pictures weren’t that bad. We all hung out in cafes in Kharkiv, in the same places where Oleg Malyovanij, Zhenya Pavlov and Bob Mikhailov were. Interested in what they were doing and because I already had a camera, I started doing my own stuff.

I remember the first time I showed my pictures to Mikhailov. He picked four out of two hundred and said, “These four are good, but the rest is shit.”

How did you end up in Sweden?

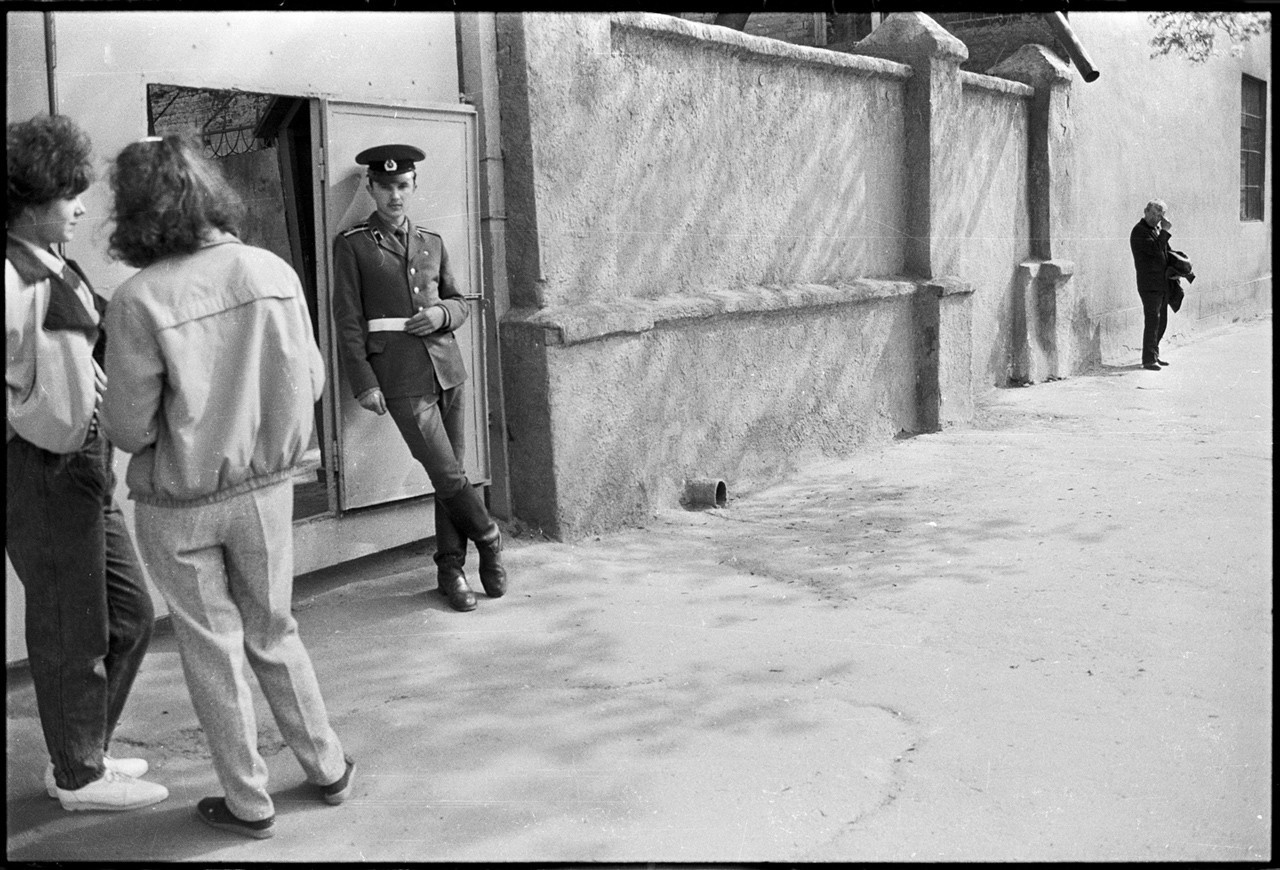

You can call me the “curator” of the first underground exhibition in Kharkiv (“F 87”). In 1987, we were able to gather the best Kharkiv photographers at the Students Palace: Mikhailov, Pavlov, Suprun from the group “Vremya,” Solonski, Pyatkovka, Okun, the group “Gosprom” where Pesin, Starko, Manko, Bratkov, Melnik, Redko and I all came from, and many others. It was a shocking exhibition at the time: 2,000 visitors per day, yelling, swearing, and the KGB who tried to shut it down. They managed to shut it eventually – “for fire safety reasons.” No one scared or intimidated me, but they did a search in the laboratory, took our fingerprints, bugged the phones and chased people from their jobs. I was the representative of the photo club.

When the “door to the West” was cracked open, we gradually started to publish and put on exhibitions.

In 1988, Roma Pyatkovka and I were doing an exhibition of our photos in Stockholm, but they didn’t allow it to go on. It turned out that the Swedes called the exhibition ‘prohibited photography.’

It went from the Soviet Embassy to the Kharkiv KGB and they really didn’t want to let us go.

Suddenly, after a month, I was called and told, “Misha, alright, you can go. Here are your and your family’s documents.” They let all of us out and later, in Stockholm, we were discussing whether to go back or not. My wife and children stayed in Sweden and I went back to Kharkiv to check on the situation. I went to the OVIR office to give back my passport (which we had to do back then), and they told me:

— Where did you come from? You came back?

— Yes.

— Wait a second, go speak to the manager.

I enter the office and the manager says:

— Misha, do you have an invitation to Sweden?

— I do.

— Then give me your passport, come back here on Monday, take it and leave.

I took my passport back on Monday. It usually took months to do this, but this time it was done in two days. I said, “See you soon.” The lieutenant colonel who worked there stopped me and said, “Misha, it’s not ‘see you soon’ – it’s ‘goodbye forever.’” I still, for the life of me, don’t understand such games. I need to go back to Kharkiv and find out if they’ve opened up the archives.

Sounds like a mystery drama. You can make a movie out of it!

It was a common occurrence at the time. There wasn’t any danger anymore: they weren’t shooting anyone or putting anyone in prison or in mental asylums. Let’s call it the remnants of luxury. The dying breaths of the system. It wasn’t much easier for those who only took landscape photos, but it was everyday life. We didn’t see anything strange in it.

Did it seem like it was all taken for granted?

Yes, but from another angle because everything was already falling apart. A week before our exhibition in Kharkiv there was a concert at the local house of culture where the group Grazhdanskaya Oborona calmly yelled into the microphones on stage, “Under communism, everything is fucked,” and the embarrassed Komsomol secretary there was burning up and tried to turn off the speakers. The adrenaline, of course, added some kind of joy; we didn’t exactly feel like heroes, but at least like we were participants in something.

You weren’t bored after leaving that scene?

I was. But old problems get replaced with new ones. While I was a Soviet photographer I was paid a lot more interest than a simple photographer from Sweden. If I had understood how hard it would be to break through, I probably wouldn’t have tried. I spent my first ten years in commercial photography. Then, however, the first financial crisis hit and there was much less demand for work. I spent the majority of my time staring out the window. My (new) wife, Anna, said, “Misha, why don’t you do anything? You won’t make any money by staring out the window. Take up your artwork again.” I started doing creative work again, putting on exhibitions and teaching. I also took part in the creation of the Ukrainian Photography Alternative.

I don’t understand. Why? As far as I know you all live well in Sweden. However, you took it upon yourself to create a community in Ukraine.

Life was too calm. I had an exhibition in Kharkiv in 2005, and while I was there they suddenly gave me a degree and made me an honorable member of the Ukrainian Photographers’ Union. I had conveniently forgotten about that and then later discovered this society’s website. I opened it and started looking through pictures of either naked girls in the snow, cats and flowers, or naked girls with cats and flowers. I was horrified by what I saw, but later I understood that there are young guys who are trying to do something but no one was listening to them. I offered to put on an exhibition and the then-chairman of the union agreed to arrange “Two Views on Ukrainian Photography.” It was obviously a bad move on his part.

I understood that the curator of “Spilka” would choose nice pictures of some landscapes, old ladies, sunsets and naked girls one-by-one. As for me, I gave the freedom to choose to photographers of the “Shilo” group and to a mixed team of photographers from Kiev and Lvov. I knew what they would choose, but I didn’t interfere in their decision-making.

It was an unbelievable event. A huge number of people from all over Ukraine showed up with their own moonshine, kissing, hugging, fighting, swearing and yelling. I said to my old friend from Kharkiv, Igor Manko, ‘I haven’t seen something like this in 25 years.’ He responded, ‘Us too.’

We decided to use this wave of strange enthusiasm to set up UPHA, which has grown to 150 members now. We don’t let just anyone in, we try to maintain a standard. I can say that, in the last few years of Ukrainian photography that is exposed to the outside world, 90% of the photographers are members of UPHA.

You haven’t updated your site in awhile, though.

We don’t do sites. What is the meaning of “Alternative?” It’s not about creating an organization or a site. Seeing that it is able to exist without financial support, we try not to make unnecessary steps. Most of the work goes into projects, so that people aren’t just exchanging information with one another, but are doing something together. There are curators that open exhibitions and choose photographers, whose work appears in galleries in different countries and begins to get published. Alternative has served as a catalyst of change.

These “Spilkis” and clubs are things that lived in the Soviet Union and to this day they try to exist by the same rules and using the same logic. They will inevitably disappear and die out – there is no need to struggle with them.

Limitations in photography, like in any other medium, serve to promote even more radical changes within it.

Of course. My students’ creative tasks often consist of limitations: “don’t go there,” “don’t look here,” “don’t use black-and-white.” I’m kidding, of course, but the point that creativity is borne from limitations remains the same, and it’s a common process.

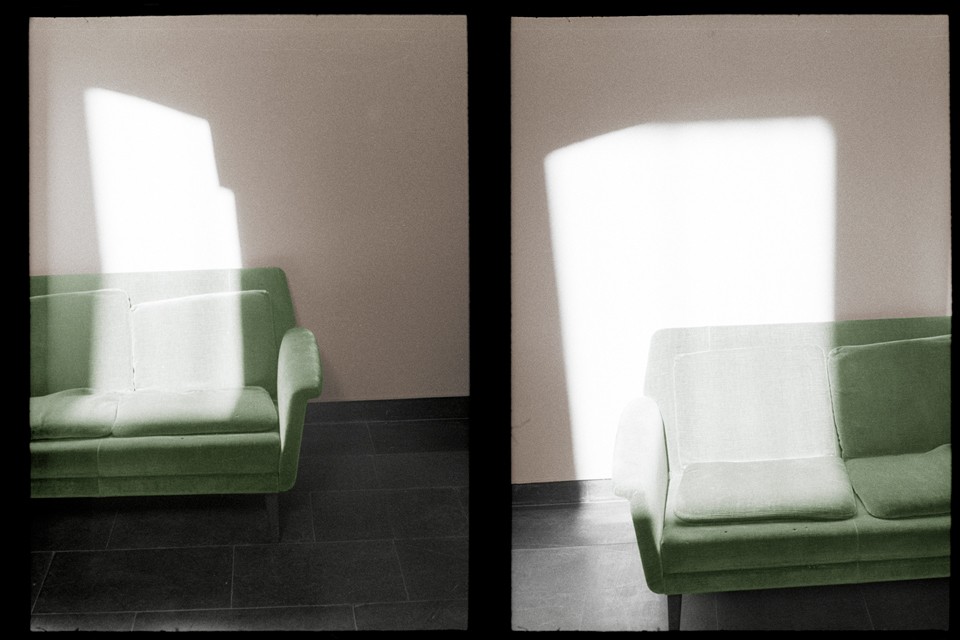

And do you limit your creativity?

I limit myself to certain aesthetic choices. That is, I don’t do photography at all. They say that now is the era of the project. However, there are photographers who do single shots and make a living off of it. That’s not very interesting, in my opinion. For me, a photo project that goes on for a certain number of years is like changing your way of life. It’s like a transition to another state where you can find yourself for some time, research it, try to live in it and then finish it. Finish it and then leave so that you can start something new – this is the actual logic of a project. And projects, for me, consist of limitations.

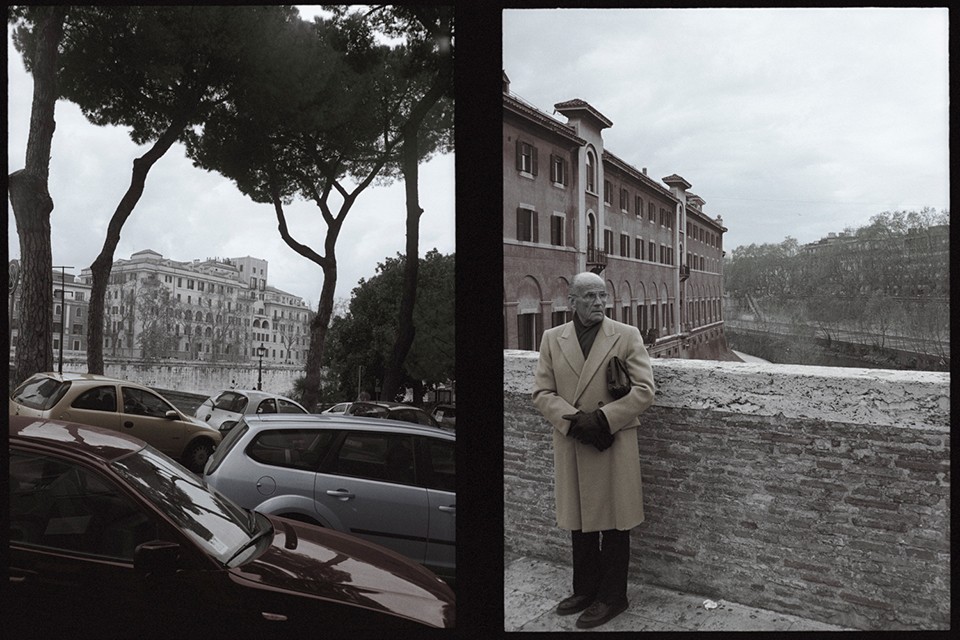

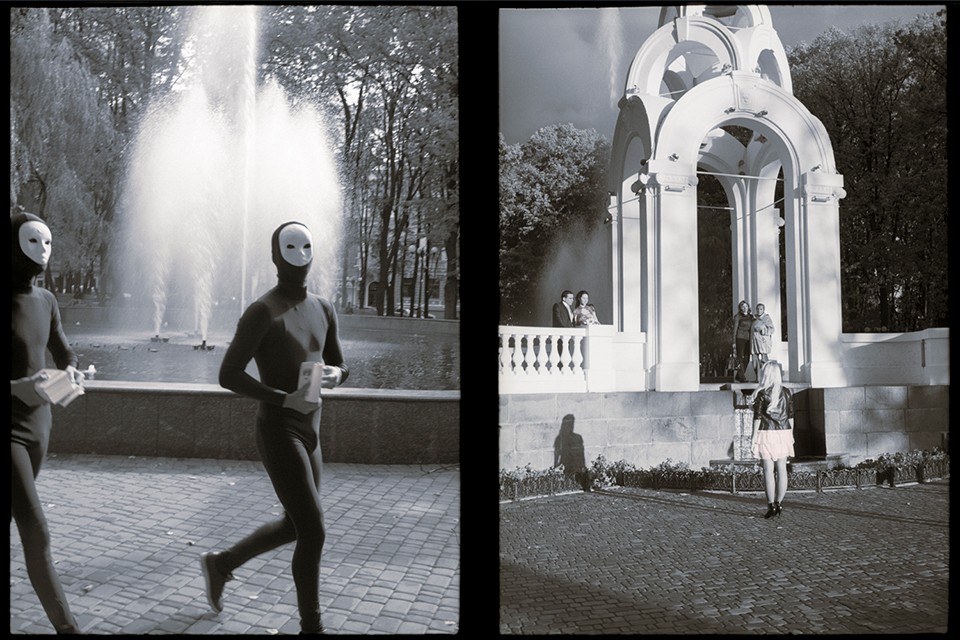

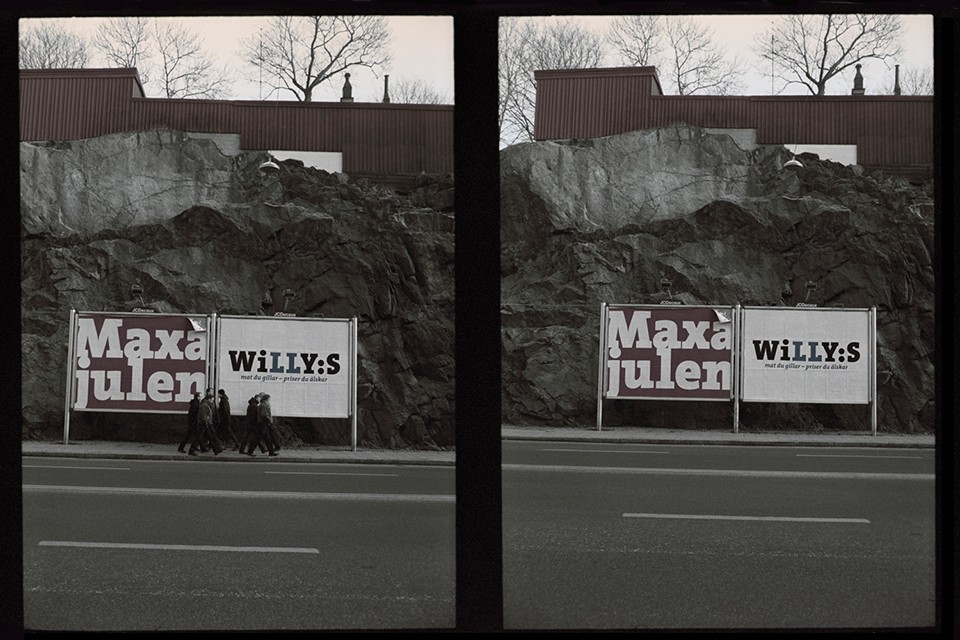

If we’re talking about books, it’s like “Star Wars” for me: the first movie is about what’s happening now, the second one is about what happened before that, and the third is the very beginning. My first book was “Stereo_typ”, a project that was made from double frames of an Olympus pen camera. After five-to-seven years of work, I understood that the only way to finish it was to make a book. After the book I had a slight hangover and I took about ten more shots, but I knew that I wasn’t going to make a follow-up.

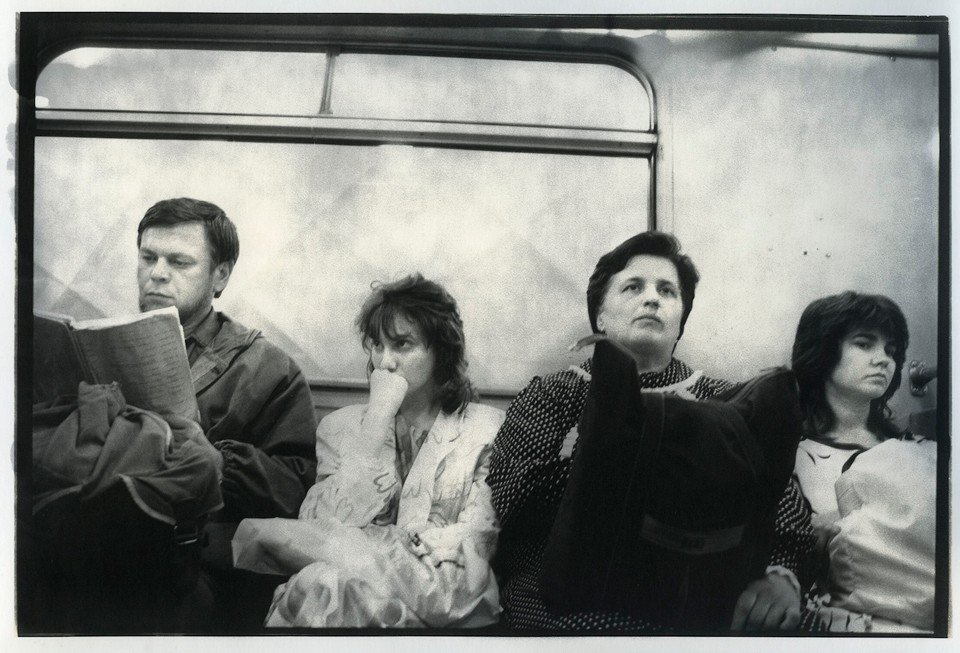

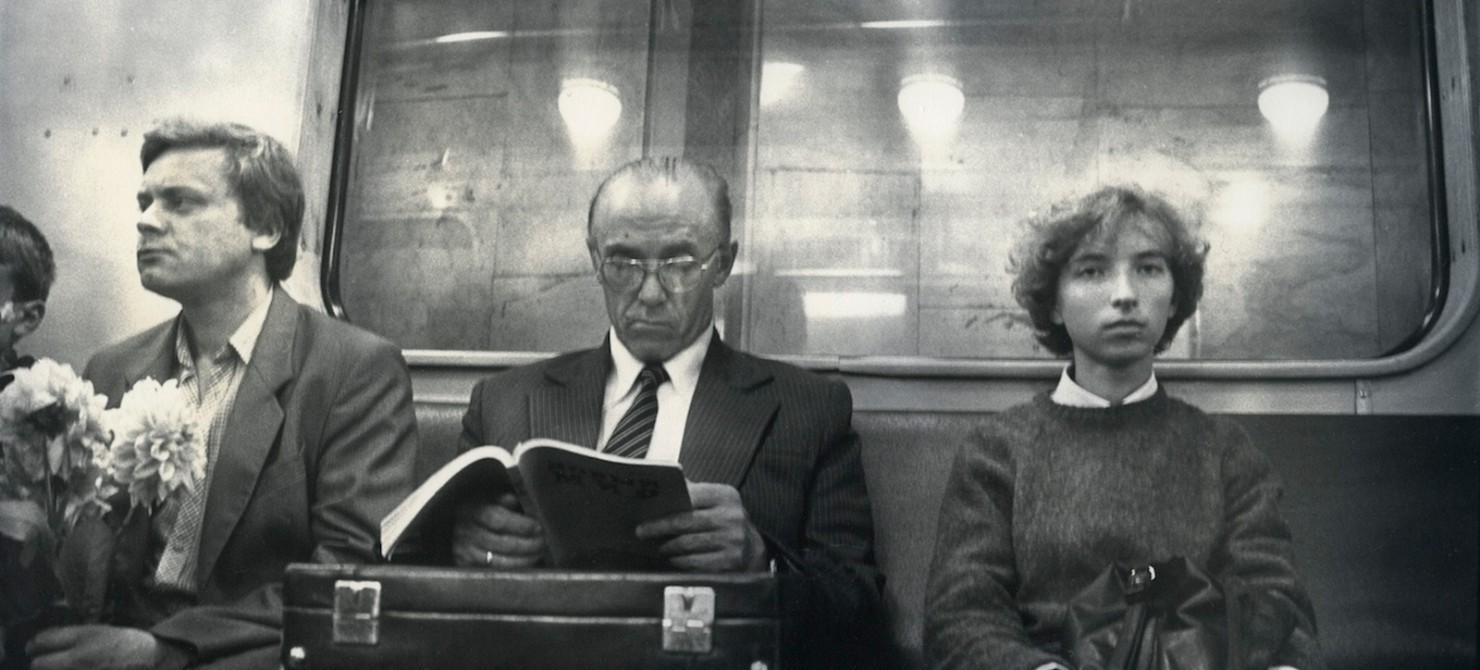

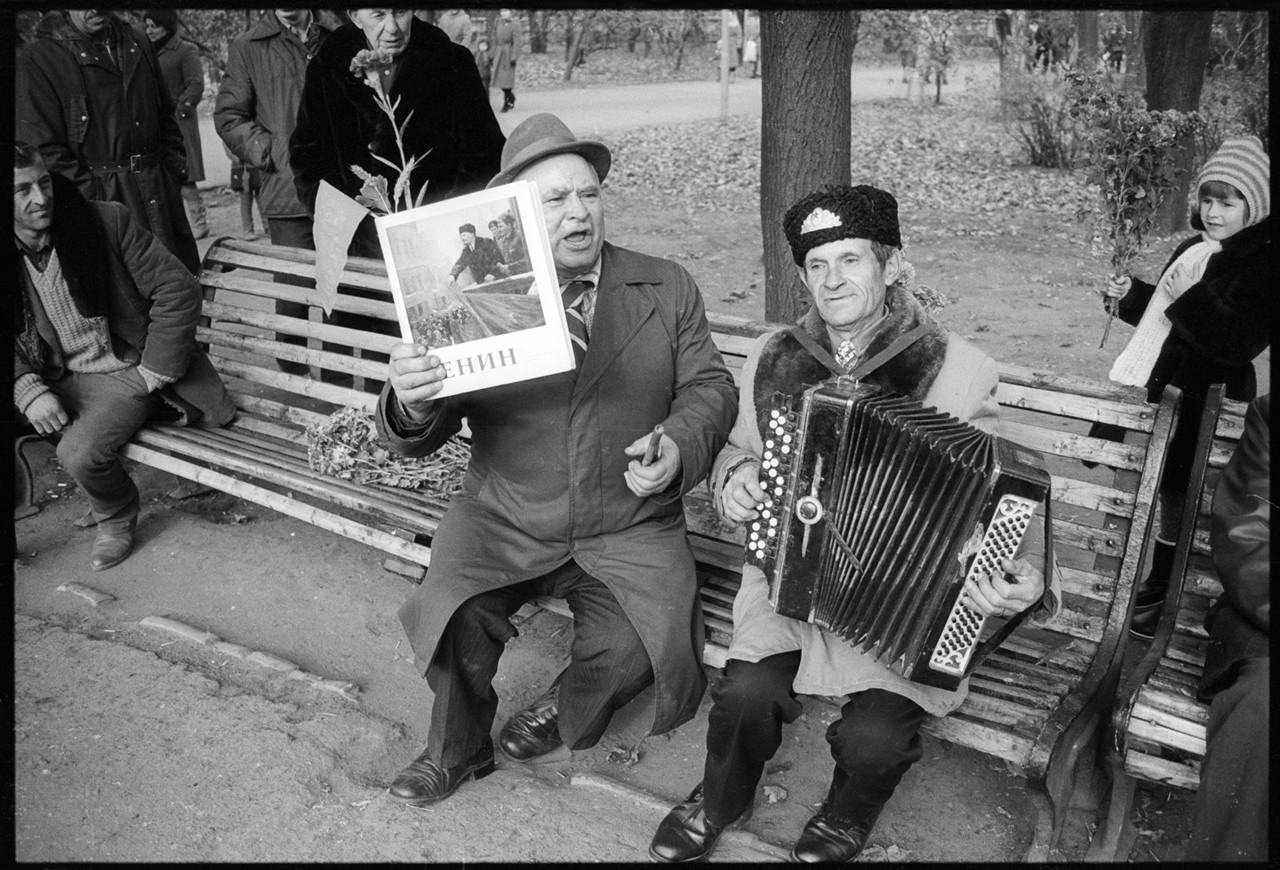

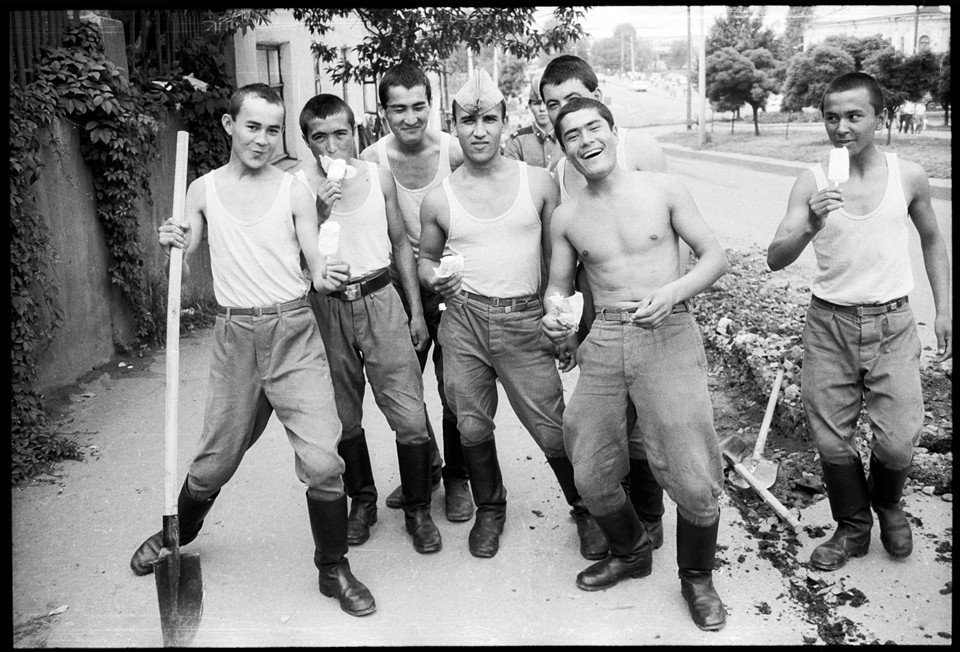

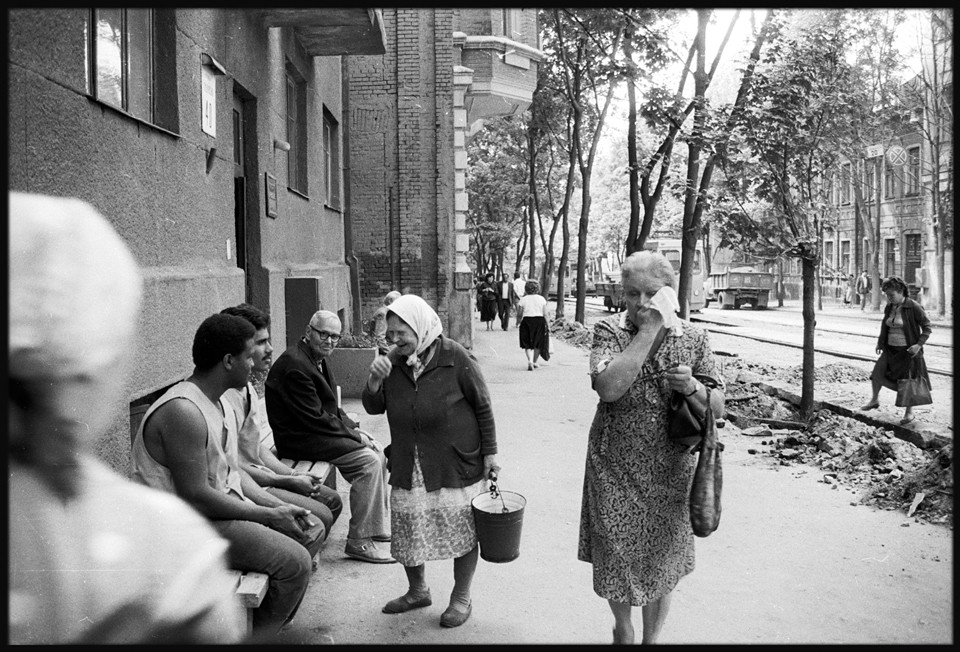

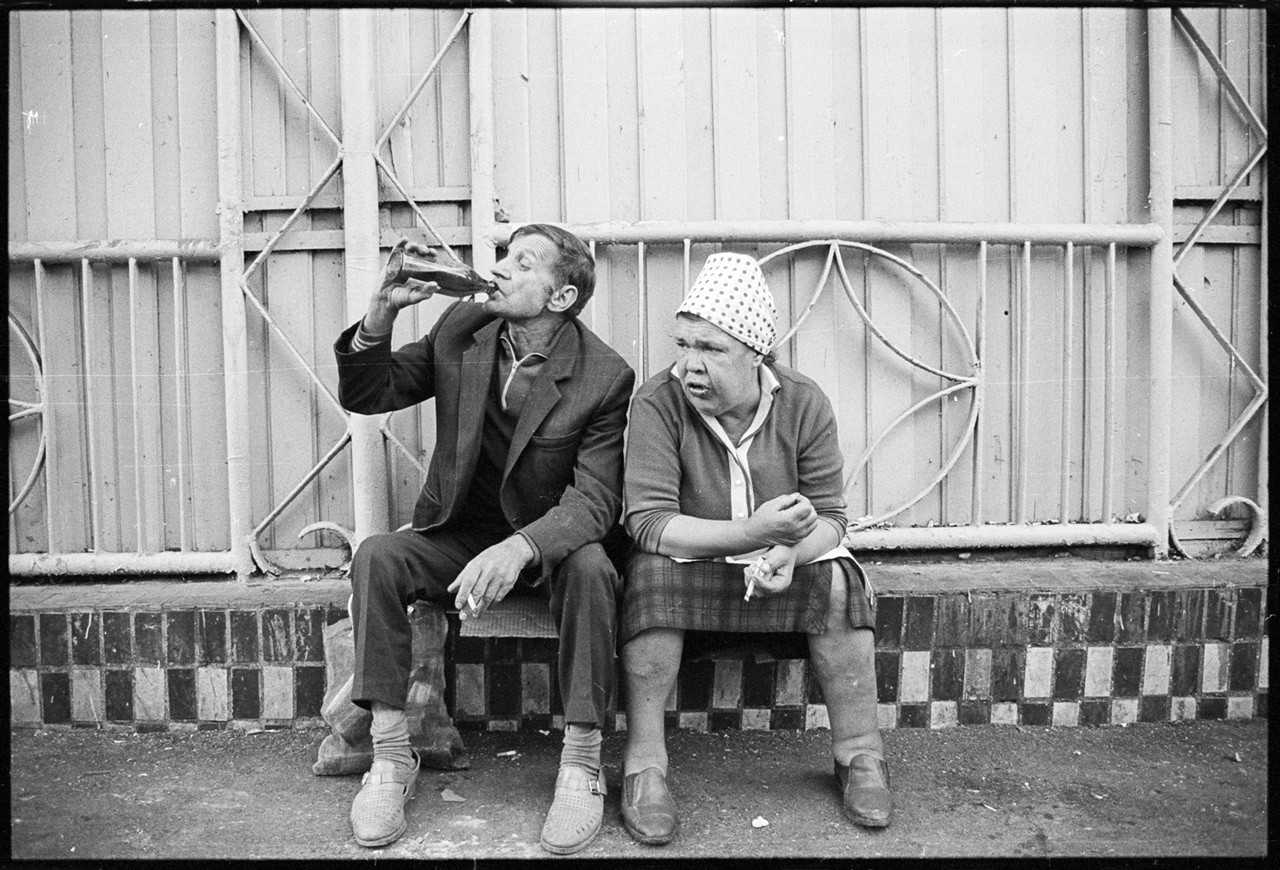

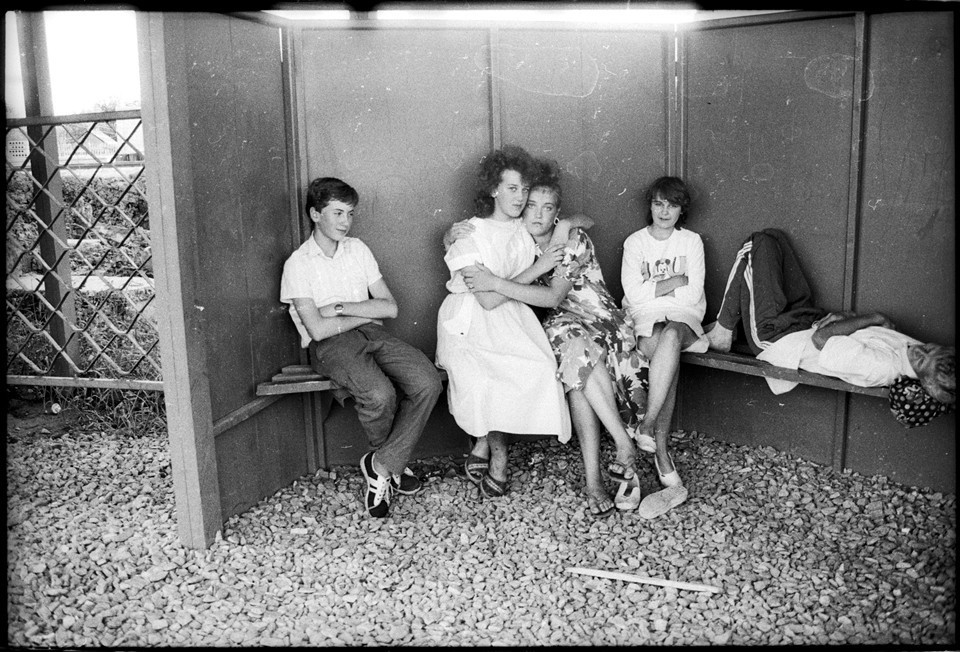

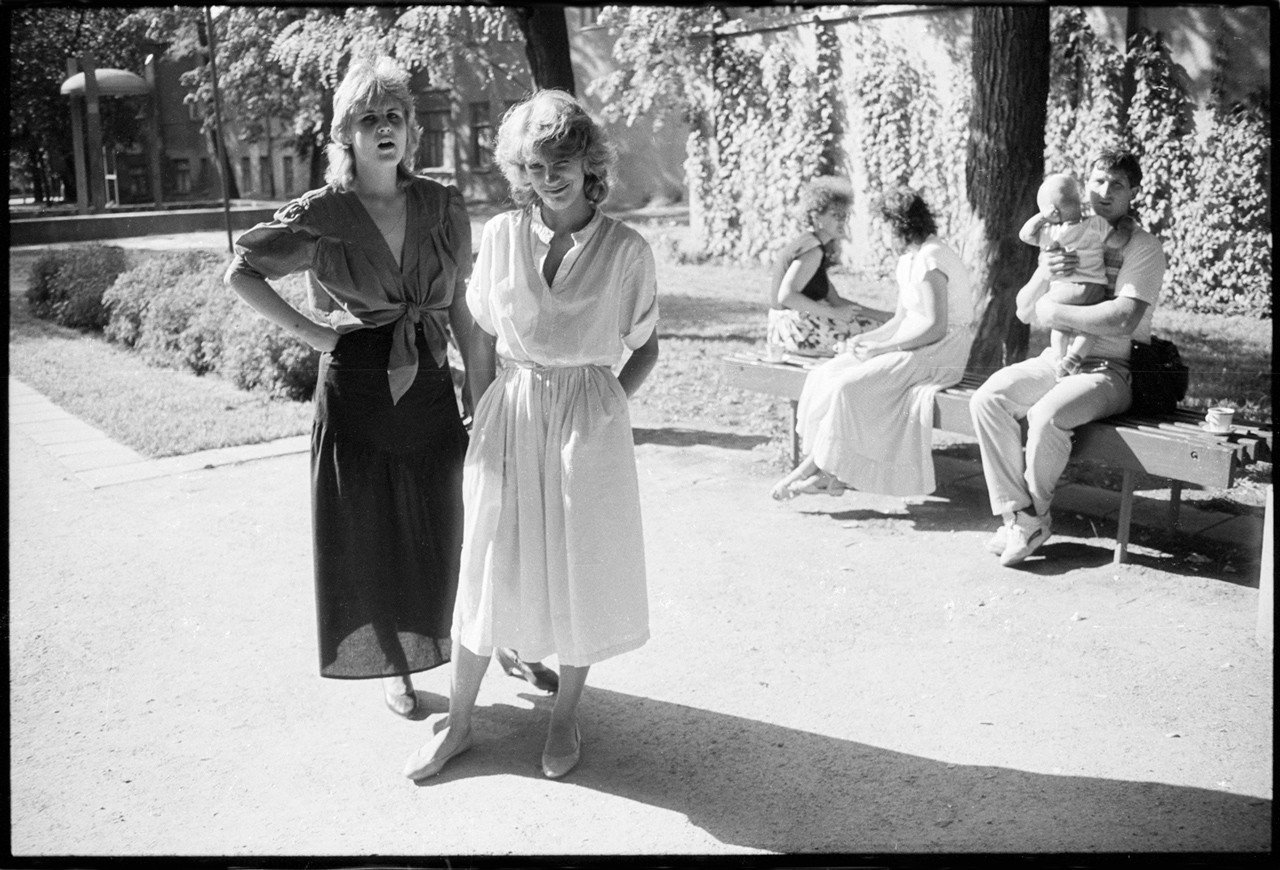

The post-Soviet book, “The End of La Belle Epoque,” for example, is me looking through my negatives from the 1980s and suddenly discovering that it was a magical time – it, of course, wasn’t magical by political or economic parameters. It was great being young and living among the good people of Kharkiv, where there was a large amount of beautiful girls and where you could walk from one cafe to another and do nothing, or do some photography.

This freedom, the first stage of freedom, was exhilarating. The book itself has a double-theme: at first it shows the Soviet exotic, but at the same time it’s a display of everyday life.

At the time, it seemed that there were hundreds of us photographers milling around and taking photos and that there should be, as a result, tens of thousands of photos. Now, you look and see five, maybe seven, books from that era. There they are on the shelf: Mikhailov and Mukhin. Not as many as you’d think.

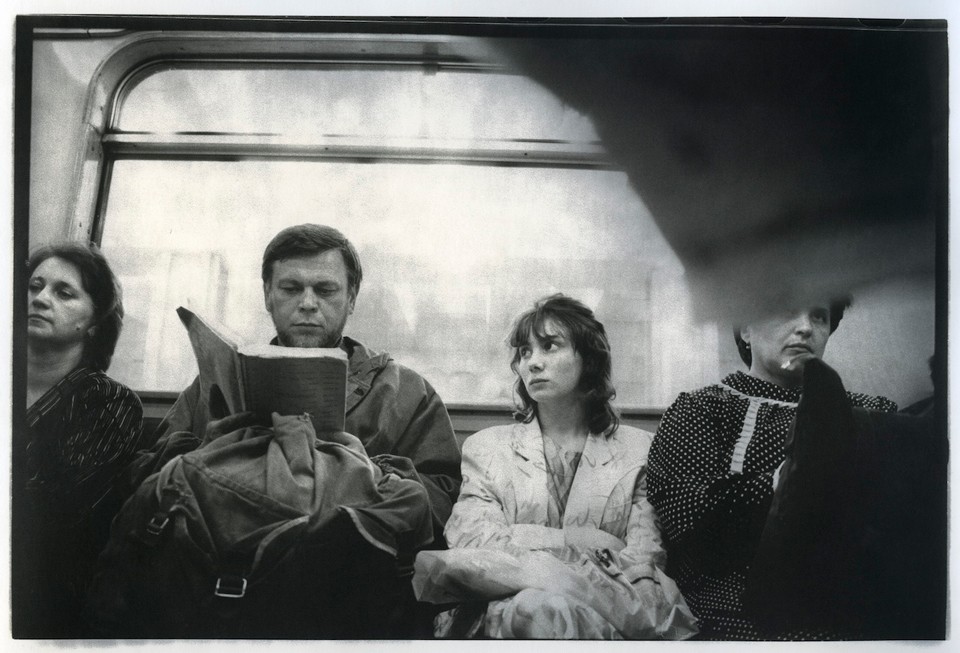

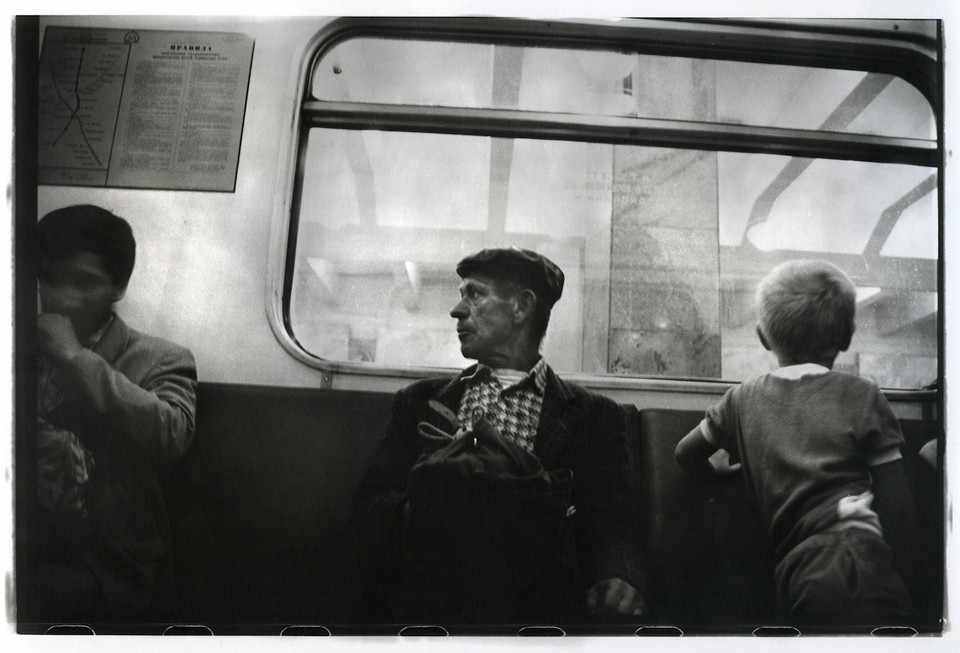

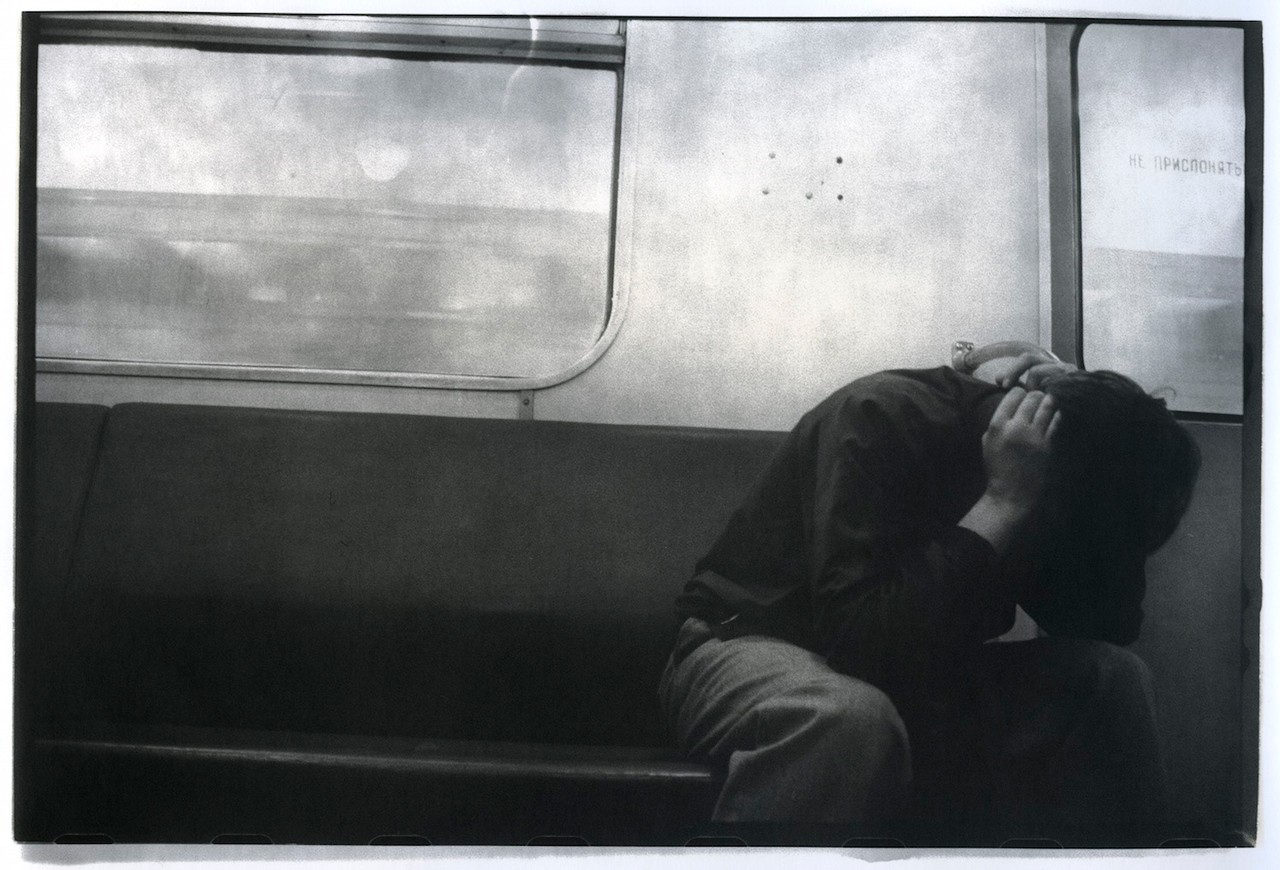

“Metro” has been a photo series for quite some time, but I never printed or published it in full. There is a very famous book about the metro by the American photographer Evans with the name “Many Are Called.” I knew that critics would tie my work to that book, and that’s why I consciously did it differently. My former student, a copyist, found photography paper from that time, 1984-85, and printed some shots. They look dark and dirty, and it was just the effect I was looking for.

The effect intensified the words of Vagrich Bakhchanyan.

Vagrich Bakhchanyan is an excellent artist and writer. His is the quote, “We are here to turn life into Kafka.”

He and I have been in the same exact places and spoken with the same exact people, except 10 years apart from each other. He left for New York 10 years earlier. He made some fantastic collages. His text about Kharkiv, however, is completely surrealist: he is the crooked mirror of the city that speaks only the truth.

I had wanted to publish that text in my book, but Vagrich, unfortunately, passed away about seven years ago, and I didn’t know how I could find who held his copyright. That’s why I called up Irina Sandomirskaya, the magnificent writer who wrote the text for my second book, “La Belle Epoque.” Irina gave me the contact info of a Russian writer in New York, and that writer led me to another writer, Aleksandr Genis, who introduced me to Irina Bakhchanyan, the widow of Vagrich. I described my project and she didn’t hesitate to give me permission to reprint the text. All of that, from the first call to Irina Sandomirskaya up to Bakhchanyan’s last word, took about an hour and a half, maximum.

I thought you were going to say “a year.”

Significantly more time was spent in search of a photo for the cover of the book. I terrorized my graphic designer. He suggested a ton of different options to me, all of which I didn’t like. In the end, I found Japanese paper that had to be delivered from Tokyo by plane. It was more expensive, but at least I liked the cover.

Are you such a perfectionist with everything you do?

Unfortunately, no. I do everything last-minute. At the same time, I don’t make compromises, and that’s not because I’m principled or something, but because I know how much you can lose with compromises. When you’re working and you finish up, and then you agree to do something just a little bit worse, all of your work goes for nothing. That’s why for me, as it is for lazy people, perfectionism is a defense mechanism against spending more time on things. Like my grandpa said once before, “We’re not so rich where we can afford to buy cheap things.”

So what’s going on now with photobooks?

The idea from several years ago that, because of the “digital age,” all of our books would now be electronic copies has gone in the complete opposite direction. It is precisely with the rise of technology that interest in photobooks as a physical object has risen higher than before. The same thing is happening with music: you can download mp3s from all over the world, but it will never fully replace live music and, in fact, will only raise interest in the latter even more. Changes in the publishing industry have taken place with the rise of computerization: we are now able to publish books on our own or at small publishing houses.

You’ll see fights breaking out over a 250-copy, limited-edition handmade book by the ‘Shilo’ group, and it’ll be a story about Cinderella.

There are always groups of collectioneers appearing, looking for new publications from new authors. A book is one of the main ways to quickly enter the international photography space.

Are there any distinctions between nationalities in contemporary photography?

We don’t have intellectual borders. There are distinctions within countries, but I can’t look at a Swedish photograph and a Ukrainian one side-by-side and say what exactly in each one is special relative to the other.

But in any case you do draw some influence from your native culture, right? Your last street photos were taken in a European style.

One very good curator, Irina Chmyreva, told me that I shoot the East as if it’s the West, and the West as if it’s the East. I can’t say that others in post-Soviet culture don’t shoot in the same style because, for example, Aleksandr Sliussarev was doing the same thing many years ago. There’s nothing new in that.

When I was a child and I was riding the tram or my bicycle, I got this feeling that the world isn’t real, like I was behind-the-scenes.

Sometimes it’s hard to believe that all of these straight lines in the city represent the real word. I think that Gaudi said that the Devil hides in plain sight.

In today’s abundance of straight lines broken down into squares, it’s often difficult for a person to find his place.

Is your last project connected to that?

What I’m working on now is connected more to my current aesthetic. I’m using the work of a famous Swedish artist, Jan Håfström. He has a series called “The Eternal Return,” pieces of which I put in my photos: a tank somewhere on the wall, a dinosaur somewhere in Brooklyn. These figures are like comic book characters, but they blend so well into our civilization that it’s practically impossible to figure out where they are in my pictures.

Jan Håfström often uses the work of other artists. This is a continuity: we are all located in one cultural plane. Taking and giving to others is the logic of working in the art world. Bob Mikhailov, looking at my book, said, “Misha, I don’t like it.” I said, “What do you mean?” He answered, “I don’t want to steal anything from you, which means, I don’t like it.” And that feeling – “I don’t want to steal anything from you, meaning, I don’t like it” – is common for me, as well.

Do you come to Ukraine?

Yes, sometimes. I always come to Ukraine with a great feeling of joy, and I always return to Stockholm with the same feeling. I don’t get enough crazy Ukrainian energy here. But, if I spend two weeks in Ukraine, I suddenly remember the phrase, “measure is a treasure.”

I was recently at a party where one young writer asked about nostalgia.

I told him that I have nostalgia, but that that nostalgia is for a country that doesn’t exist. It’s for a Kharkiv that doesn’t exist anymore.

It happens when you suddenly find yourself in a place that hasn’t changed at all. Life, however, has changed, the situation has changed and the mentality has changed. This country is not the same. However, as Vagrich said once before, “In Kharkiv, they’re giving children data that is unnecessary for sex education.”