Mari Bastashevski: It Is Important to Understand Why You Are Looking for Secrets in Connections Between the States and Corporations

Business on state security, cooperation of authoritarian regimes with global corporations, which are making money on military contracts, selling weapons and cyber spying — photographer Mari Bastashevski investigates not only these topics, but also the informational vacuum that surrounds them. Each of her projects is the result of years spent learning about the subject; it is investigative journalism, photography, and contemporary art.

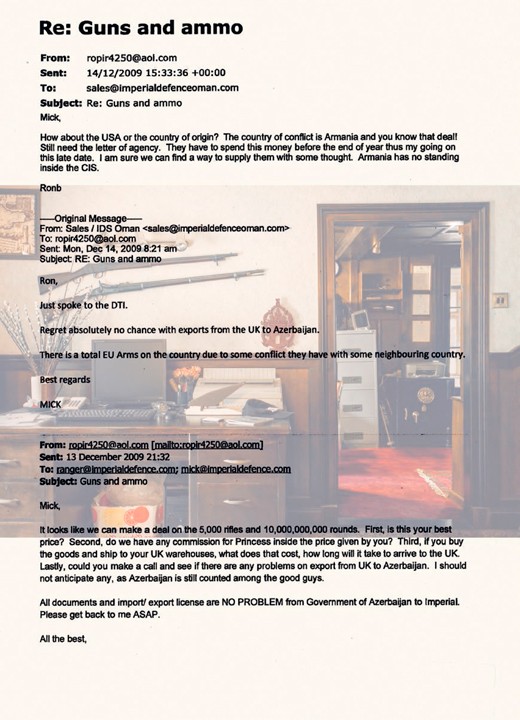

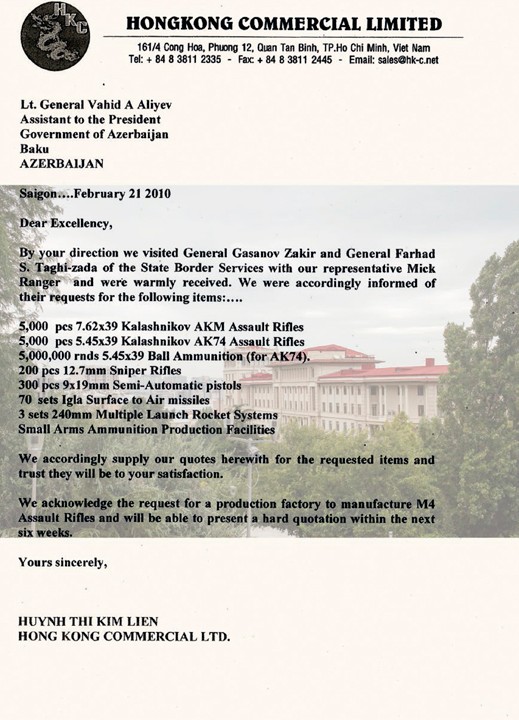

Bastashevski traveled around dozens countries, studied many hundreds of documents and sent countless information inquiries — all of this for the photographs, in which, it seems, almost nothing is going on. ‘Photographing the unphotographable’ — this is how Simon Shuster from the American magazine Time described Bastashevski’s method. There are no scenes of violence or military action in her project about international conflicts. “We can photograph men in business suits at some arms exhibition, and we can photograph children with Kalashnikovs somewhere in Africa. But a lot happens between these two points.” — Bastashevski explains.

In her Bird in Flight interview, Bastashevski talks about why she does not work at the frontline when covering conflicts, how she receives permission to shoot from officials who avoid publicity and why Ukrainian secret services do not spy on their citizens on the Internet.

Born in St. Petersburg, lives in Switzerland and Ukraine. Her works were exhibited in Elysée-Musée de l’Elysée, Art Souterrain, Noorderlicht, Le Bal, Open Society Foundations, Polaris Gallery and East Wing; and published in Aperture, Wired, Time Magazine, New Forum, The New York Times, Courrier International, Le Monde, VICE. In 2014, Mari was one of the finalists of Prix Elyse, and in 2012, she received a Magnum grant. She studied art history and political sciences in Copenhagen. In 2011, she spent a year in Cite Des Art residence in Paris.

The geography of your investigations extends to over twenty countries, but you keep coming back to Kyiv. When and why did you start working in Ukraine?

Ukrainian companies and state authorities are active players in the international network of military conflicts. This is why Ukraine often gets in my viewfinder. The first work visit in 2011 was related to arming both sides of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. A lot of details about successful cooperation of the European countries with the Yanukovych regime came up during the investigation, as well as information about the commercial participation of a number of Ukrainian companies and state institutions in conflicts in Libya, Sudan, Somalia, Mali, and Syria.

Has anything changed since then?

After my recent visit to Kyiv international military industry fair I can surely say that the business benefited from the war in Ukraine.

Your series called State Business is about the war, but there are no usual images of military action in the photographs. What is this project about?

Recently someone had a quick look at the publication and wrote on Facebook:

“Just some military guys having lunch, some office with some examples of antique armor, a corridor, a business lunch on the roof, and so on and so forth. These are all rather simple situations in the places, which we have all seen. Without connection these images do not convey the meaning.”

And this person accidentally nailed it.

So what do you answer when they say nothing is going on in your photographs?

My position as the author is somewhere at the edge of catastrophe and in situations where what is going on is not an event in the news journalism understanding of the word. My events lie on the surface, and at the same time they are not obvious. Photography allows for the creation of form for the invisible. This is something we pass by every day without taking notice. I am not looking for these situations on purpose, it is just that the decisive deals and meeting happen in these mundane spaces.

Do you consciously avoid shooting at the frontline, of direct military action?

The concept of the frontline is outdated. It may be applied only to some parts and episodes of the war. Where is the frontline, when a drone does not see its target? Many conflicts today last longer, but with are less intense, many turned into special operations, and the controlled territories change hands almost ritually, to enable all parties to have their share of the revenue.

How do you manage to obtain permission to shoot from people and structures, who avoid publicity and prefer to stay in the shadows?

Very often I do not. It is intellectual masochism. In response to every refusal I ask those who prohibit me to shoot about the extent of their prohibition: if I can’t shoot here, can I shoot at the door? How about behind the door? 25 meters from you? The question usually confuses my counterpart, distracts them from their official curtseys and creates a window for spontaneous dialogue. This question allows the hero of the story to define their perimeter of power, whether it is imaginable or legal. When I exhibit my works, I expose these secrets, mentioning the type of the source, and the allowed shooting distance.

You investigate secret processes. Does the general public really need to know it all?

Everybody has to decide for themselves, what they need or do not need to know. Rather than passive knowledge about some secrets, it is more important to understand how and why to look for information about the business of states and corporations, their connections. This process is sometimes called culture hacking, and may be applied to different scenarios, for instance to broaden the rights and possibilities of civil society.

Is there a lot of classified information, which you discover as you work, left off screen?

A couple years ago I started a folder of ultimately sincere ‘do not open before my death’ letters. This resulted in the whole archive of secrets, divided by category: ‘do not open before my death A’ and ‘do not disclose before immigration B’.

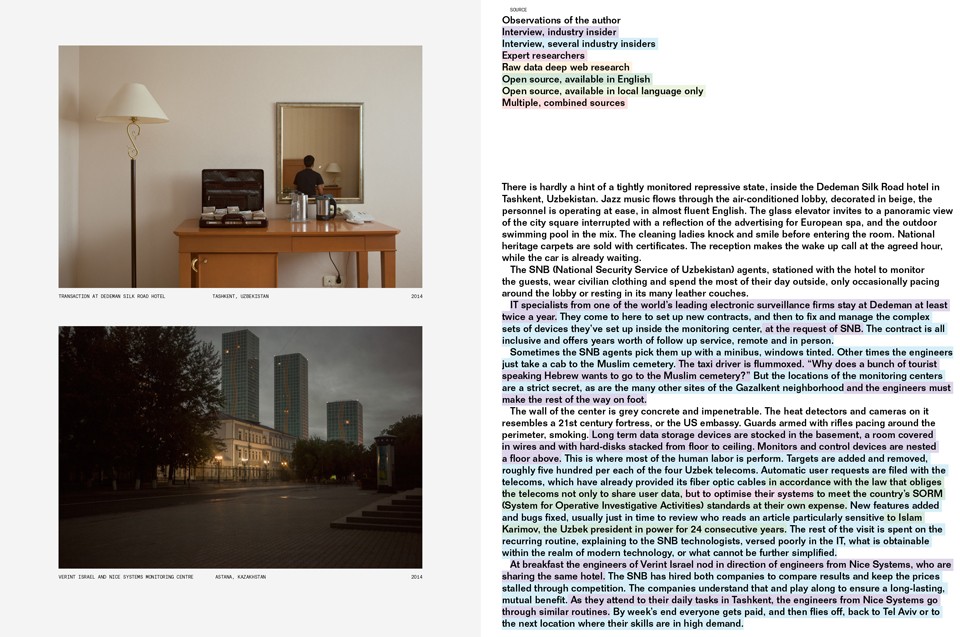

However, I procure a lot of information for my works from open sources. For instance, some of the information about the contracts of Alcatel Lucent, a French company, about providing SORM (or Law Enforcement Support System [LESS]) in Central Asia may be found with the help of basic Google commands. All advertising catalogues from It’s Nothing Personal project are also easy to find, using the instrument ‘search for text files’ on the servers of the companies. All of this information is in open access. And of course, a lot is accumulated in social networks. For instance, a European consultant for a large American company in Russia, who was at some point responsible for a deal between Rosneft and TNK-BP, which was very important for Putin, even left several of his home addresses on the web.

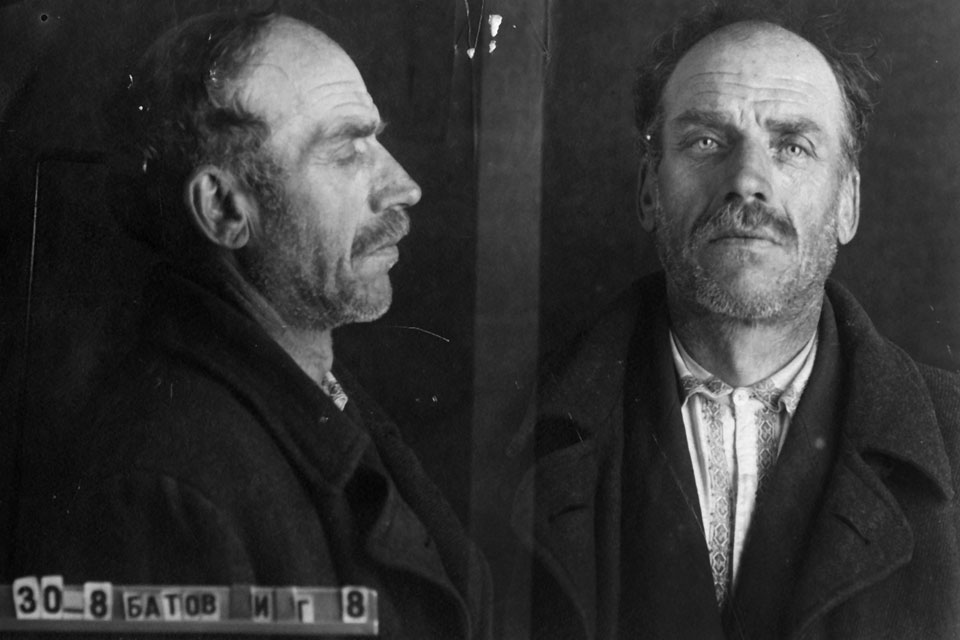

After your project about people kidnapped by the military and secret services in the North Caucasus — Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan — you were prohibited from entering Russia. Did you expect this?

No. In the mid-2000s, many journalists and photographers worked in the Caucasus, it was slightly easier back then. Yes, there were cases of detainment, especially in Dagestan. But at that time, when human rights activists Stanislav Markelov, Natalya Estemirova and Gadzhimurat Kamalov were alive, it was hard to imagine that an exhibition of the photographs of empty rooms in New York City and France would cause such a reaction from the FSB. Looking back — yes, it must have been predictable.

What were you looking for in Libya, when the Gaddafi regime was collapsing?

I was in Libya by chance, and the war, or rather, war theater, started as soon as I got there. What is still interesting about Libya — Gaddafi’s close relationship with the Western politicians, who suddenly noticed that Libya had huge problems with democracy. Before his regime fell, the CIA and MI6 used Gaddafi’s help to manage secret prisons, and they very well knew about the torture in them. In the mid-2000s, BAE and Finmeccanica companies helped the regime to install Internet monitoring centers and procure weapons. The regime returned the favor by contributing to the budget of Union for a Popular Movement, a party, which supported Nicolas Sarkozy, during the 2007 election in France, and invested in private property and business in Italy via the state investment fund of Italy LIA.

Your latest work is about covering the activities of companies, which provide mass Internet spying services. Who are their main clients? How are the systems they supply used? Do you know anything about Ukraine?

Their clients are the CIA, FSB, Vatican, Europe, as well as all dictatorships of the world, except maybe North Korea. It is not about who the clients are, but what mechanisms exist to control those who are using these technologies against their people. Ukraine used to buy something minimally from Verint Israel, but, as far as I know, total Internet surveillance is not yet in place here. Most probably it is not because they respect the private space of their citizens in Ukraine, but because there is not enough money to work with a large amount of data of a big country.

What does the Hacking Team cyber group do?

Hacking Team did not invent anything ingenious. They buy information about vulnerabilities of popular applications in the open market, minimally process it, and then sell them under the name Galileo as viruses for millions of dollars. Galileo is a product aimed for a certain device (unlike mass surveillance systems). The virus gets into the user’s computer through baits such as fake iTunes and Adobe family programs updates. This system was used by law enforcement to spy on dissidents in Bahrain, Central Asia, Ethiopia and many other countries. On July 5, 2015, Hacking Team were hacked by the hackers for their grandiosity and impudent lies to activists and hackers who tried to counter them.

Why do you stick to documentary practices?

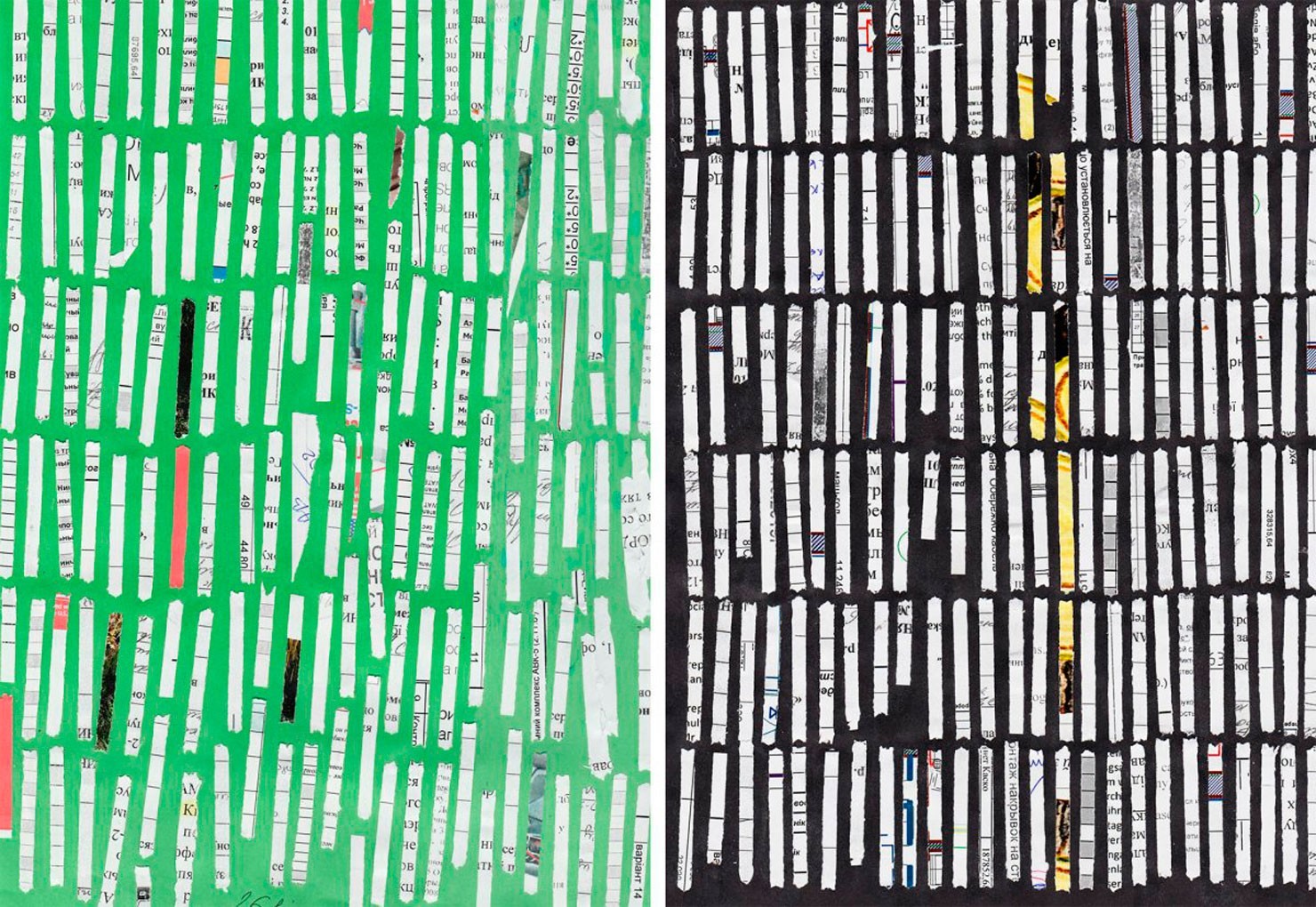

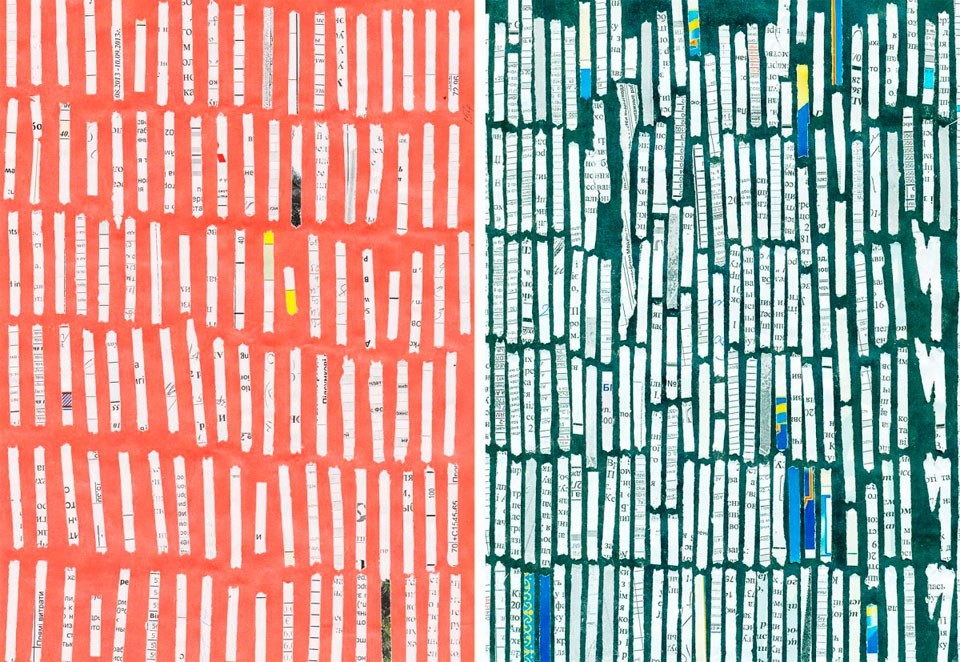

I am not sure I stick to them. When journalists were working on the shredded Kurchenko archives (Ukrainian businessman Serhiy Kurchenko is considered to have managed the finances of the Yanukovych family; he fled the country in February 2014. — Ed.), they did it with the clear intent of finding out the truth and restoring justice. I use the same pile of documents in my installation as an object. And it is more interesting for me to understand the motivation for the effort to reconstruct these documents. Why do both those who destroyed the documents and those who glued them back together still have this unwavering trust in the legal system, knowing very well that it does not work?

Ukrainian artists, photographers, journalists — do their works live up to the bar, which is set by the scale and complexity of events?

The only bar, which the scale and complexity of events set, is to survive. Everybody has a different understanding of survival.

And yes, journalism here often suffers from the wish to help.

But it is impossible for a journalist to be objective, if the conflict, sometimes literally so, occurs in their backyard.

And it is counterproductive to demand that you be detached and objective in this situation. Perhaps, at some point transparency can replace objectiveness.

The situation of the artists here, and I am talking about a narrow circle of people who are doing contemporary art, is absolutely undefined. There are absolutely no guarantees, and the perspective for professional survival or confidence about what to do in the context of the external conflict with Russia (the pre-war lexicon lost its meaning, as did the connections), and in addition there are many internal confrontations. On the one hand, there are commercial organizations, which identify themselves with the world of art and survive by measuring their input in this sphere in kilograms and in kilometers (and if it could be ignored earlier, now under the current circumstances it looks grotesque). On the other hand, there is reactionary vandalism, which sometimes turns into direct violence. This existed before, but in the context of the conflict it became more apparent, and it seems impossible to preserve the status quo.

You balance between the role of an investigative journalist, an artist and a photographer. Isn’t it time to choose one?

What for? I use journalistic methods in my investigations, as well as academic research methodology, these languages are convenient for me, and if I want, I can make the material into an article or an academic report. But how I present the completed work and what questions I am trying to ask most often leads to exhibitions in the format of contemporary art. The very possibility to combine these roles and think about their boundaries is the privilege of the artist. The investigation informs the art, the art informs the investigation. And in this constantly ongoing process they are merged into one for me.