The Revitalizing Effect: 7 Photographers Who Dabble in Film

Photography is similar to cinematography in searching for images, noticing small details, and experimenting with light and composition. Thus, it isn’t surprising that many directors, before finding themselves in film, searched for these images and details in still photos, wandering through the streets with a camera. At the same time, others returned to photography after having tried things out in film. Bird In Flight chose seven photographers who, having shot their first films, left photography for film and became better for it, if at least not worse off.

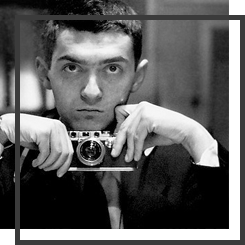

Stanley Kubrick

Cinematic realism on the verge of documentary reporting turned Kubrick into a star in the 1970s. “If you want people to believe your story, only use natural light. And remember that the most expressive thing is a spontaneous moment.” He shot several cult feature films that will always be admired. A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange caused loud responses when they were released; no one had ever touched on the themes of man and the universe and of man and violence as skillfully as Kubrick.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_01.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A scene from the film, A Space Odyssey.” }

Agnes Varda

Her first film, La Pointe Courte (1955), is about the fishermen of a coastal village and was taken to with great admiration by French youth at the time. Varda thought everything out from start to finish — geometrically well-formed frames, actor selection and adjustments of each replica. Despite this, at that time Varda was looking for inspiration from a dozen other films. Modern critics call her the grandmother of the French New Wave — her first film looks like nothing that had been seen in French cinema prior, but this is not quite true. She was certainly close friends with the chief rebels of the “wave,” Godard and Rivette, but later she admitted that the structure of her films was different than that of her husband’s films, Jacques Demy (director of Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, which is also included in the “wave”).

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_02.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A shot from the film, La Pointe Courte.” }

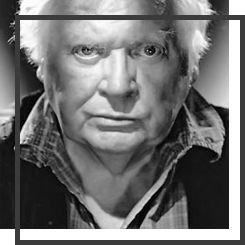

Ken Russell

port cafe where everyone was doing the jive or the teddy, boys and girls of the 1950s who fancied themselves as “pre-war lords.”

“I also wanted to shoot for fashion and so I arranged a photo shoot with my friends who were dancers. A woman’s hat, a stroller, a bath and everything was in business.” Later on, his surrealism and eccentric images (for example, as an experiment he portrayed ballerina Frances Pidgeon as a turtle with a bathtub on her back) successfully migrated into his films. Russell showed his first short films to producers at BBC and he was offered a job at the station in cultural programs.

Many critics reproached him for vulgarity, and it’s true for his first two pictures. In the early 1960s, his work went virtually unnoticed. However, Women in Love was praised for its brightness, rhythm and violence. If there was someone that Russell didn’t like, he showed no mercy. His fiery personality is visually represented in his films. For example, in the biopic-parody Lisztomania (1975), he turned the character of Wagner into a risen-from-hell Hitler because of his distaste towards Wagner’s music.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_03.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A shot from the movie Women in Love.” }

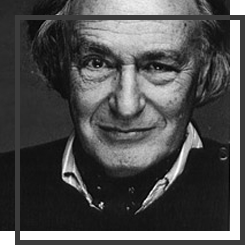

William Klein

His documentary debut (shooting neon signs on Broadway) became the complete opposite of his street photography (motion blur, high contract, capturing accidents — all violations of the taboos of his time). His first feature film, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo, was of course about what he knew better than anyone else — a satire on the world and behind-the-scenes of fashion. After all, in addition to “street photo projects,” he shot for Vogue for ten years.

When he became known as a pioneer in street photography in the late 1980s, having influenced a generation of photographers in Europe, America and Japan, he again returned to the world of photo art. However, he continued to experiment more in the field of graphic design.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_04.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A shot from the film, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?” }

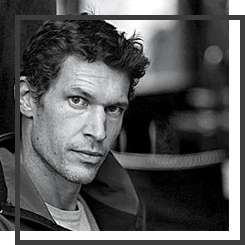

Anton Corbijn

In one interview he admitted that the first film he did was made as an experiment, as they say, just do it and relax. But after the success he signed a contract with the studio Focus Features for his second film and George Clooney starred in the main role. The move to film became a move forward for Corbijn, “I’m constantly in the middle of searching, and that’s probably how I’ve avoided creative crises.” Today he remembers with nostalgia how reporting from street concerts gave him a special charm for his next job, “Focusing around while shooting gives a sense of community, and an undedicated singer in the foreground against a coarse grain of film gives texture and physical palpability.”

Corbijn’s fourth film will already hit the shelves at the end of 2015. Life talks about the friendship between actor and rebel James Dean and photographer Dennis Stock and both person’s road to stardom. Today, a portrait of a 24-year-old Dean in Times Square, taken by Stock not long before Dean’s death, is considered a classic of photojournalism.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_05.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A scene from the film, Life.” }

Tim Hetherington

“People who have never been in a war imagine it to be like the news or Hollywood. This is a barrier to understanding. It was important to show the humor, boredom, and confusion inherent in fighting.” Therefore, everything in the movie is the brutal truth: depression, existence, enemy fire, trenches and bullets ripping through bodies, and it doesn’t matter under which flag you are fighting. Restrepo won the Grand Prix at the Sundance independent film festival. Hetherington was killed in 2011 during a fight in the Libyan city of Misrata.

{ “img”: “/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/moviephotographers_restrepo.jpg”, “alt”: “”, “text”: “A scene from the film, Restrepo.” }

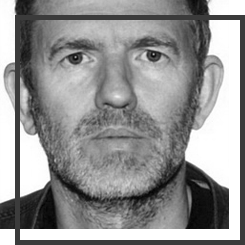

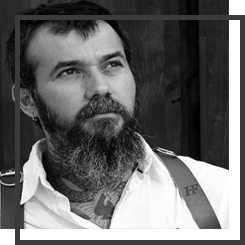

Pep Bonet

Practically every one of his photo projects, be it on the war in Sierra Leone or the life of transsexuals in Honduras, has won a prize at a major photo exhibition. His short film “In the Shadow” (2013) about migrant workers in Johannesburg and how they fight for housing, work and food, also attracted international award bodies, including the World Press Photo Multimedia Contest.

Today, when every person has a camera, Bonet is convinced that photography can not be a simple hobby: “You need to understand your responsibility and take it upon yourself. After all, a photo is something akin to the relationship between car and driver.”

Teaser for the short film, “In the Shadow”.

New and best