Chernobyl: How the Series About the Tragedy Was Made

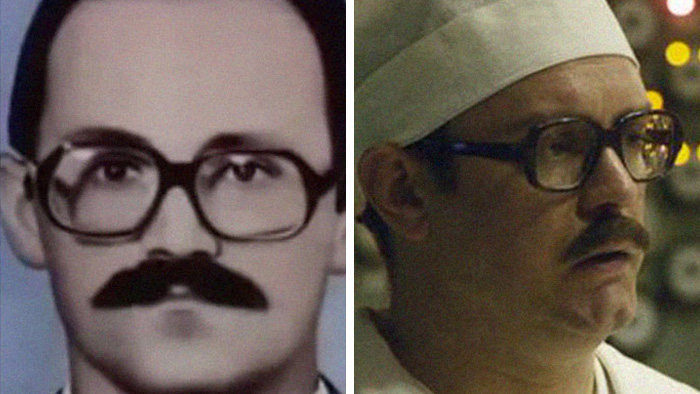

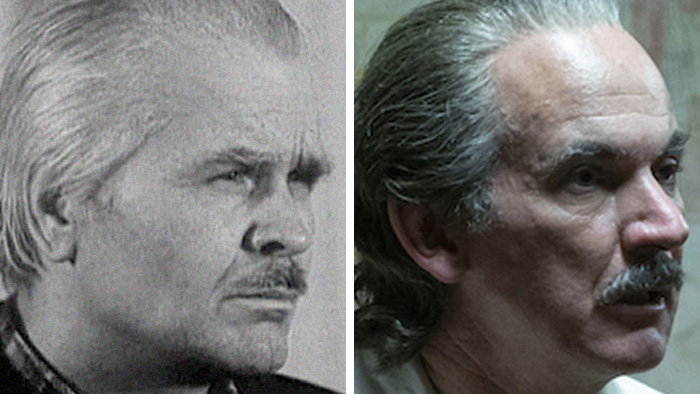

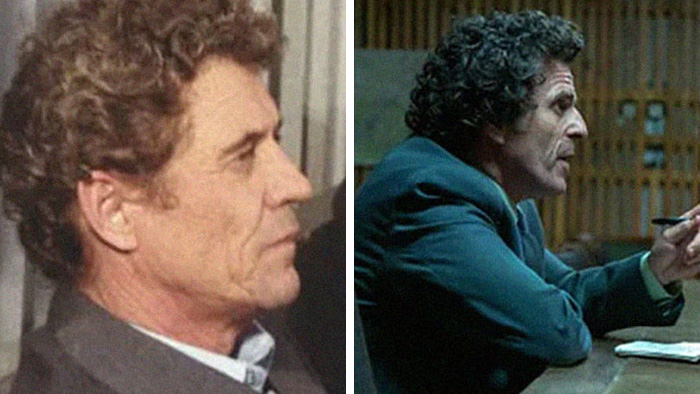

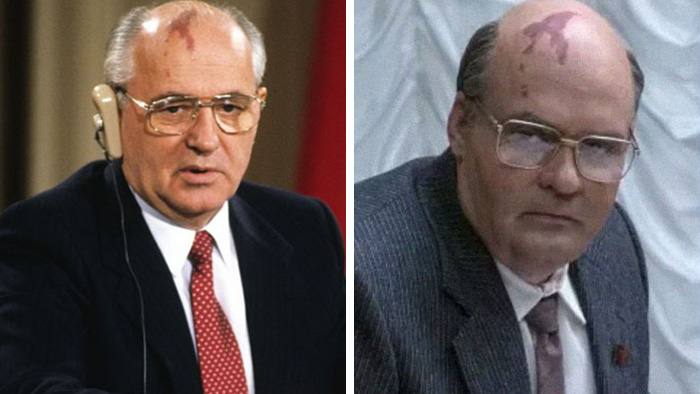

Chernobyl is a fictional series and not a documentary. However, the creator, screenwriter, and executive producer of the project, Craig Mazin, calls his child a docudrama: he spent hundreds of hours studying the documents, memories of the witnesses, accident reports, and documentary chronicles. It took Craig over two and a half years to do research and prepare for writing the script (this was not his only job). It is amazing how immersed he is in the project: he knows about the accident many times more than a regular Ukrainian — a person, directly impacted by it.

The miniseries was released over a little more than a month — five approximately one-hour episodes. The creators also have a podcast for each of the episodes where Mazin explains minor deviations from historical truth and artistic decisions. For instance, he deliberately placed Legasov’s suicide in the opening scene. He says that it was fair — for the viewer to be looking at past events and understanding that the protagonist is dead.

Where It Was

The series was filmed in Lithuania and Ukraine. Lithuania was chosen to decrease the budget: it is one of the countries where tax for filmmaking can be decreased if local professionals are involved — and there were enough of them there who were able to work on a show of such scale. For Mazin’s project, the tax was decreased by 20%. According to the creators, it was the lack of such conditions that resulted in only one third of the series being filmed in Kyiv and Pripyat. The fact that there is a partially closed Ignalina NPP in northwestern Lithuania with the same type of reactor as Chernobyl was an advantage — but it wouldn’t have been that important without the favorable taxation scheme.

In Lithuania, the tax was decreased by 20%.

Some of the events in the series took place in Moscow and Minsk, but going there for a couple of extra shots is additional spending (not only technical, but also on tax), that’s why Kyiv played the role of neighboring capitals. This is typical: the same happened in The Death of Stalin, a movie that is prohibited in Russia. And in BBC America’s hit, Killing Eve, Moscow scenes were filmed in Bucharest — the tax relief there was 35%.

The white building of Taras Shevchenko National University playing the Central Committee of the Communist party of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic is not an exoticization of Soviet reality or lack of respect to Ukrainian history, but a pragmatic solution that saved costs and allowed spending to be redirected for other purposes, such as detailed decorations and eerie sound design.

Details were important for the team: Legasov’s garbage bin, faceted glasses, the clothing of the Pripyat population — everything corresponds to the period. Kyiv flea markets were scoured for decorations — and this was where they found old clocks, ashtrays, and phones. Costume designers were worried about the accuracy of recreating the uniform of firefighters and first responders, but it turned out to be easier than they thought: for instance, there was just one version of firefighter uniform. It was also the one recreated in the series: tarpaulin work clothes, gloves, and helmet. Some clothes were sewn in Lithuania and some were purchased online.

Comrade Khomyuk

Meticulous historical research and fiction get mixed already in the first episode. The scene of the accident is recreated minute by minute and has well-placed documentary inserts — such as the real conversation with the firefighting service dispatcher or a news piece. And at the same time, we have Ulana Khomyuk.

The scene that introduces her is real: according to Mazin, this was exactly how the change in background radiation was noticed on one of the NPPs close to Chernobyl. However, Ulana herself is a collective image of scientists who helped deal with the aftermath of the accident. There were many more such professionals that it would seem from the series: according to Anna Korolevskaya, a consultant of the series and deputy head for science of the ‘Chernobyl’ National museum, up to 40 ministries participated in it, and each of them had an operation headquarters with a task force.

It is not an accident that a woman collectively represents those scientists. Mazin says that although

In scenes with Gorbachev, they show a woman several times, but she never speaks

The truth is, as usual, somewhere in the middle. It is not the best solution to create a noteworthy series in 2019 without a solid female character. And the character, though bearing traits of ‘female’ socialization, is well-written and well-played, which makes it smoother. It is hard not to empathize with comrade Khomyuk — this may be the reason why viewers get so upset when they find out that Ulana did not exist.

Naked Truth

Another highly discussed solution is the miners getting naked in episode three: the Internet jokes that it wouldn’t have been an HBO series without naked people.

Miners from Tula indeed dug a tunnel under Chernobyl NPP: 150 people from Novomoskovskaya and Nikulinskaya mines, as well as the Tulaugol association arrived in Chernobyl on May 14. And although consultants and government officials say that the miners couldn’t have been naked, first responder Sergey Trofimov said in his interview to E1: they knew very well that the uniform wouldn’t save them from radiation, so they took their clothes off. In the podcast, Mazin explains this is not artistic means, but a real depiction of events.

It is interesting how nudity is one of the chief accusations to the series and is perceived as something that undermines the honor of the miners. This is an interesting allusion to the main motive of the series — to lie about the scope of the accident, but to save the honor of your country. Is getting undressed in 50C heat really something so horrible and shameful?

Is getting undressed in 50C heat really something so horrible and shameful?

However, the series is not always physiologically accurate: in her interview to Iod, Korolevskaya says that the faces of first responders were made redder for bigger effect. Depending on the radiation dose, the skin could have turned not only red, but pale white, and the redness did not normally show so quickly.

Korolevskaya also said that it was not General Pikalov from Moscow who went to measure the radiation levels, but Aleksandr Logachev. They didn’t have to cover the vehicle for his trip with led, as there were ready solutions equipped with a dosimeter. There are other inaccuracies: for instance, the helicopter fell into the reactor much later than it was shown in the series (on October 2, 1986, during the construction of the sarcophagus).

The prevalent use of ‘comrade’ has mixed reviews — however, Mazin says it was included at the insistence of Ukrainian consultants.

Words from the Voices

It is interesting how director Johan Renck approached the presentation of the characters: he worked with the gait and posture of the actors so that they could show the weight of the past on the shoulders of the characters. Mazin speaks about a hundred years of hardship and grief that are part of Soviet identity. It is partially also conveyed through words — in the monologue of the elderly woman in episode four. She lists everything that she had to go through: from bolsheviks and holodomor to the new invisible threat.

There is a bit of a scandal surrounding this scene. Ukrainian screenwriter Pavlo Arie on his new Facebook page accused the creators of the series in plagiarizing the monologue from his play. However, there is nothing in common between the two texts apart from their general direction and mood, and the image used there is rather universal. Mazin wrote on Twitter that he had not read Arie’s plays, and the scene was inspired by one of the stories from Voices from Chernobyl by Alexievich. Like in the series, her character is milking her cow and refusing to leave her land and house.

The plot line of pregnant Lyudmila and firefighter Vasily is also borrowed from Voices. The creators of the series received permission to use the book, but the writer herself hasn’t seen HBO’s Chernobyl yet.

Chernobyl had an impressive ending: each episode had a higher viewing average than other HBO hits: specifically, Barry and Veep, which had much bigger advertising budgets. In addition, the ratings of the show grew from episode to episode, which is an exception for the ‘peak TV’ epoch, when a high start and drop in viewers over several episodes, and then an average number by the last third of the show is typical. The total rating for the series on IMDB is 9.7 out of 10.

It may be because the series with the slogan ‘The cost of lies’ was painfully honest — both in terms of accuracy and in terms of drama. Craig Mazin and his team managed to show the horror of the Soviet accident and its human faces.

Reuters already reports the increase in demand for visiting the exclusion zone among foreigners — so we will wait for tourists and study our history. It seems that we will still need to explain to our guests that vodka is a popular drink, but not a must.

All images courtesy HBO.

New and best