Cities That Aren’t: Oleksandr Ranchukov’s Archive

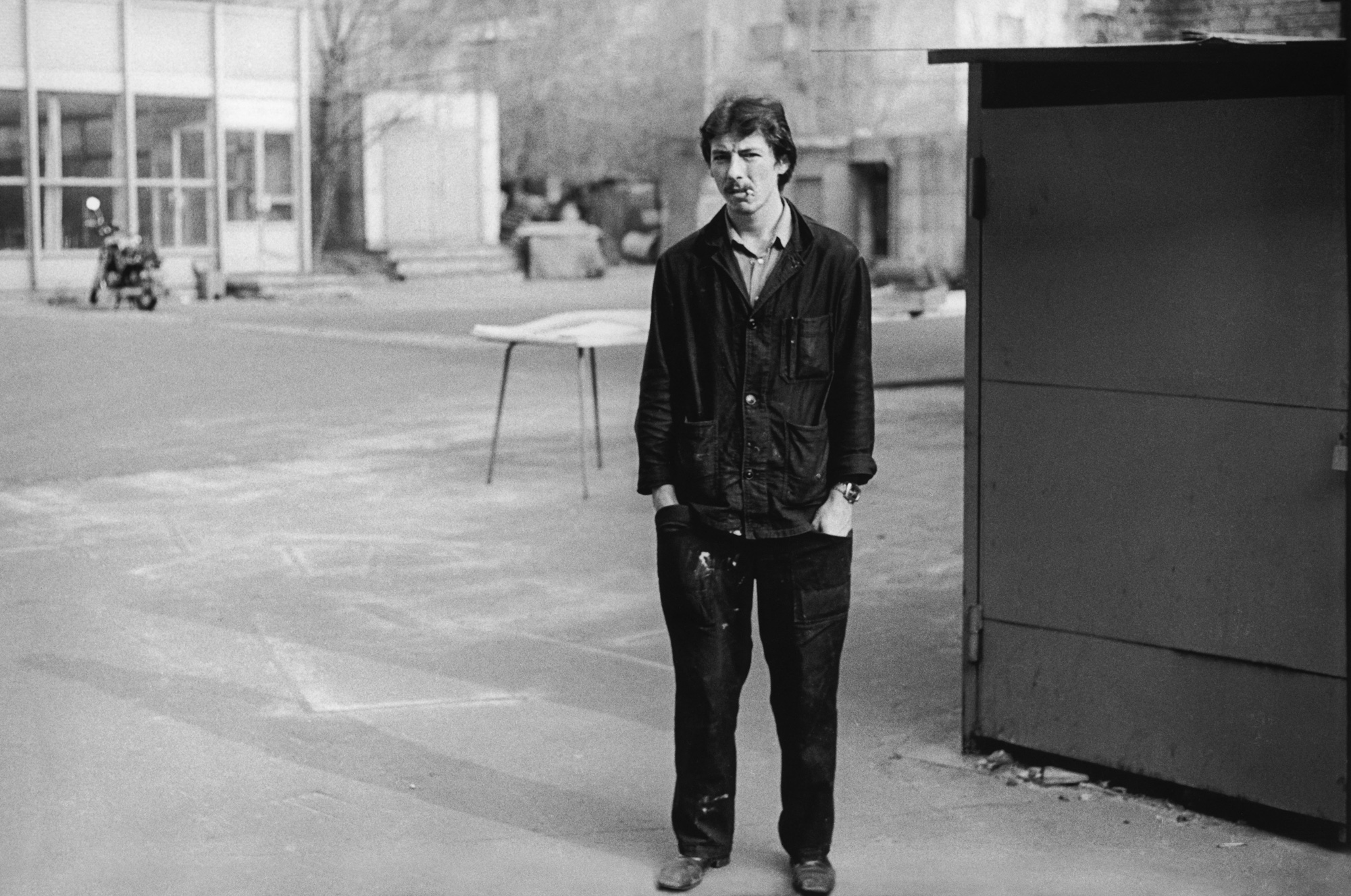

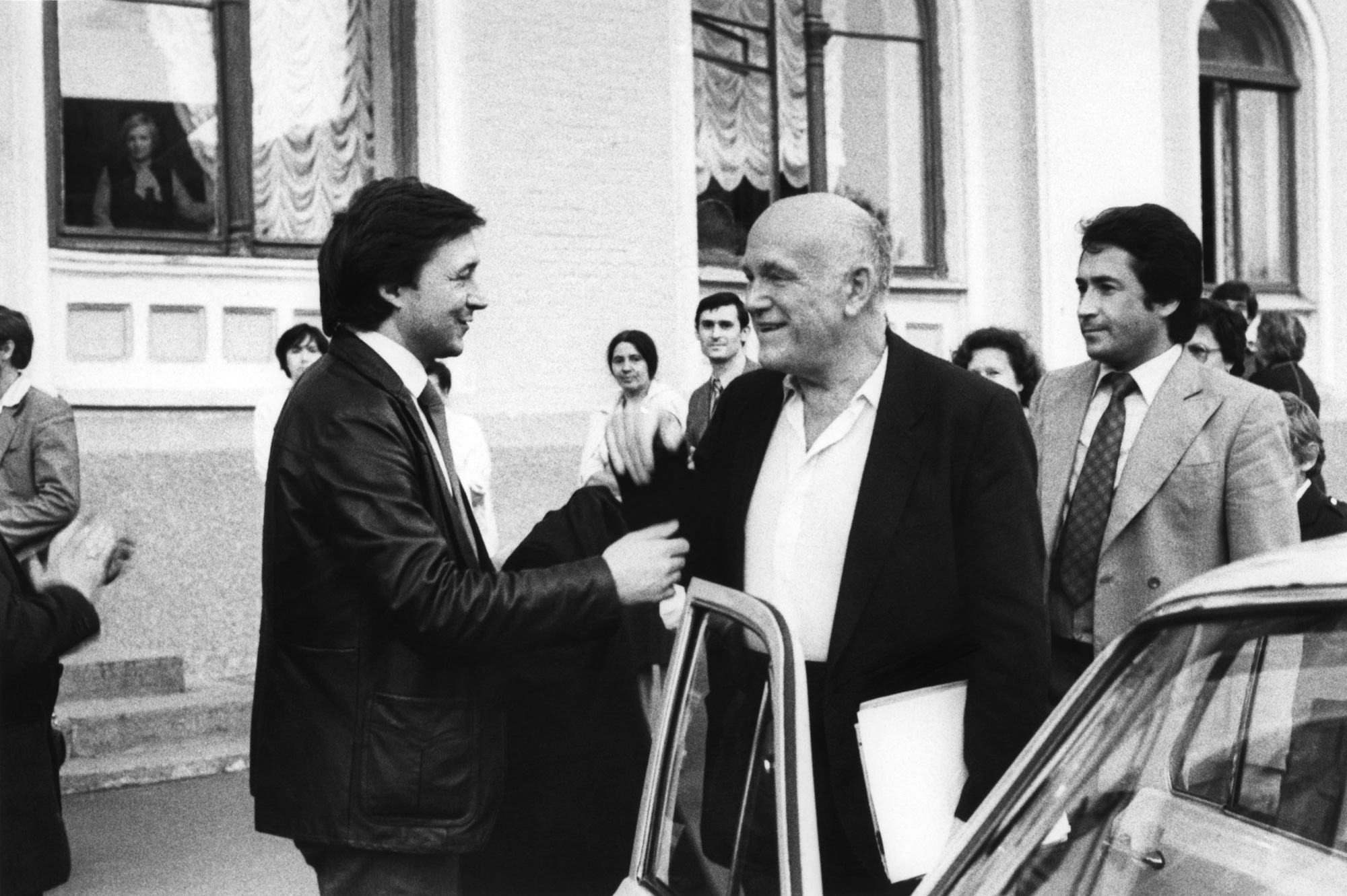

Oleksandr Ranchukov is an author of several books about Kyiv and numerous photographs of the city. He was active in the photographic movement: in the years of perestroika, Ranchukov initiated Pohliad (‘Outlook’) association that had a lot of influence on the development of documentary photography in Ukraine — and included Efrem Lukatsky, Oleksandr Gliadelov, and Rita Ostrovska. Pohliad exhibitions were closed by the KGB and party authorities, and some patriots wrote in the comments book that the participants should be shot.

Ranchukov fought to preserve the historical and architectural heritage, theoreticized in creative photography, and was a thinker. As a photographer, he became the chronicler of Ukraine of the times of the former USSR.

A Viscous Time of Sad Faces

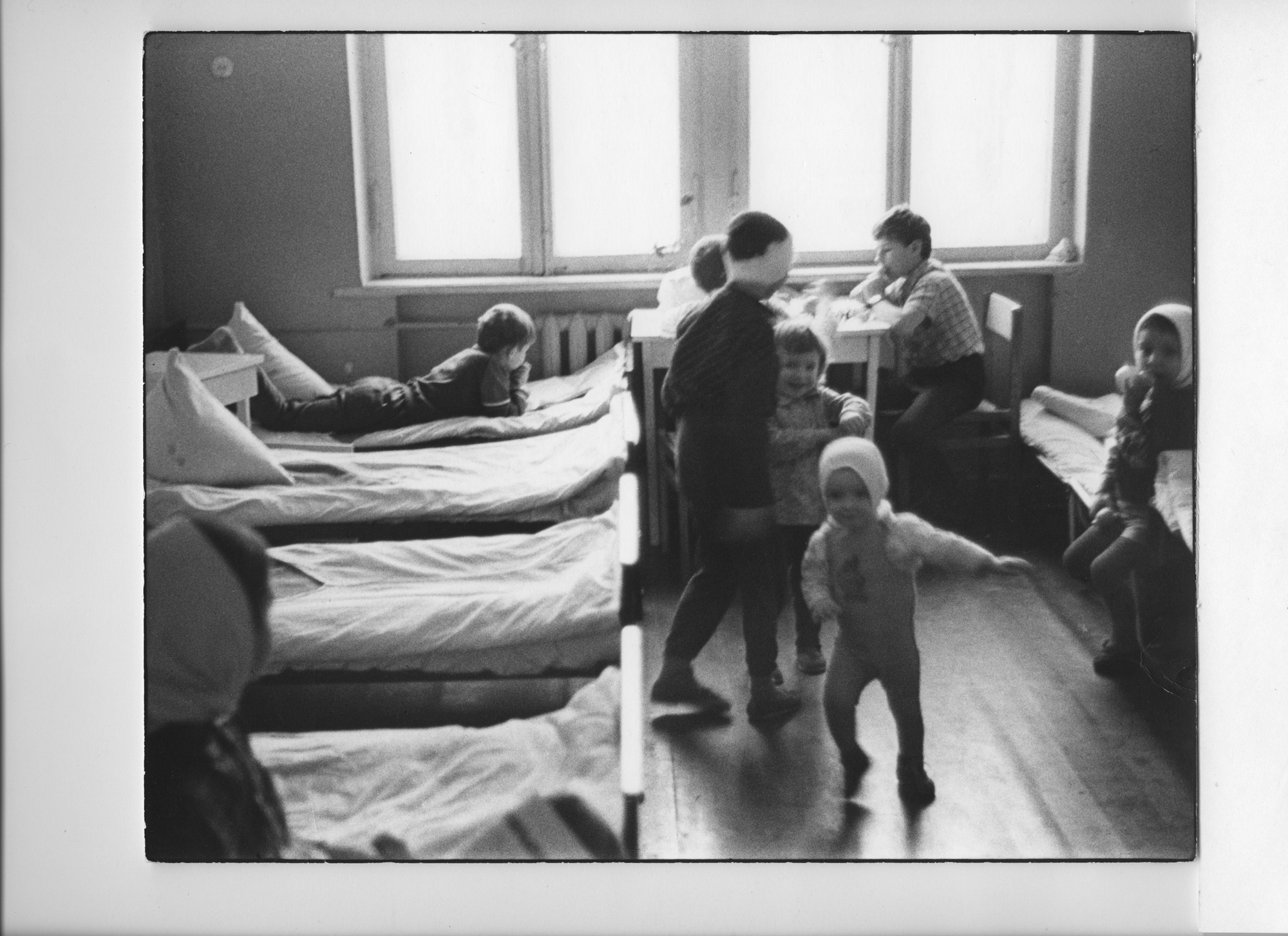

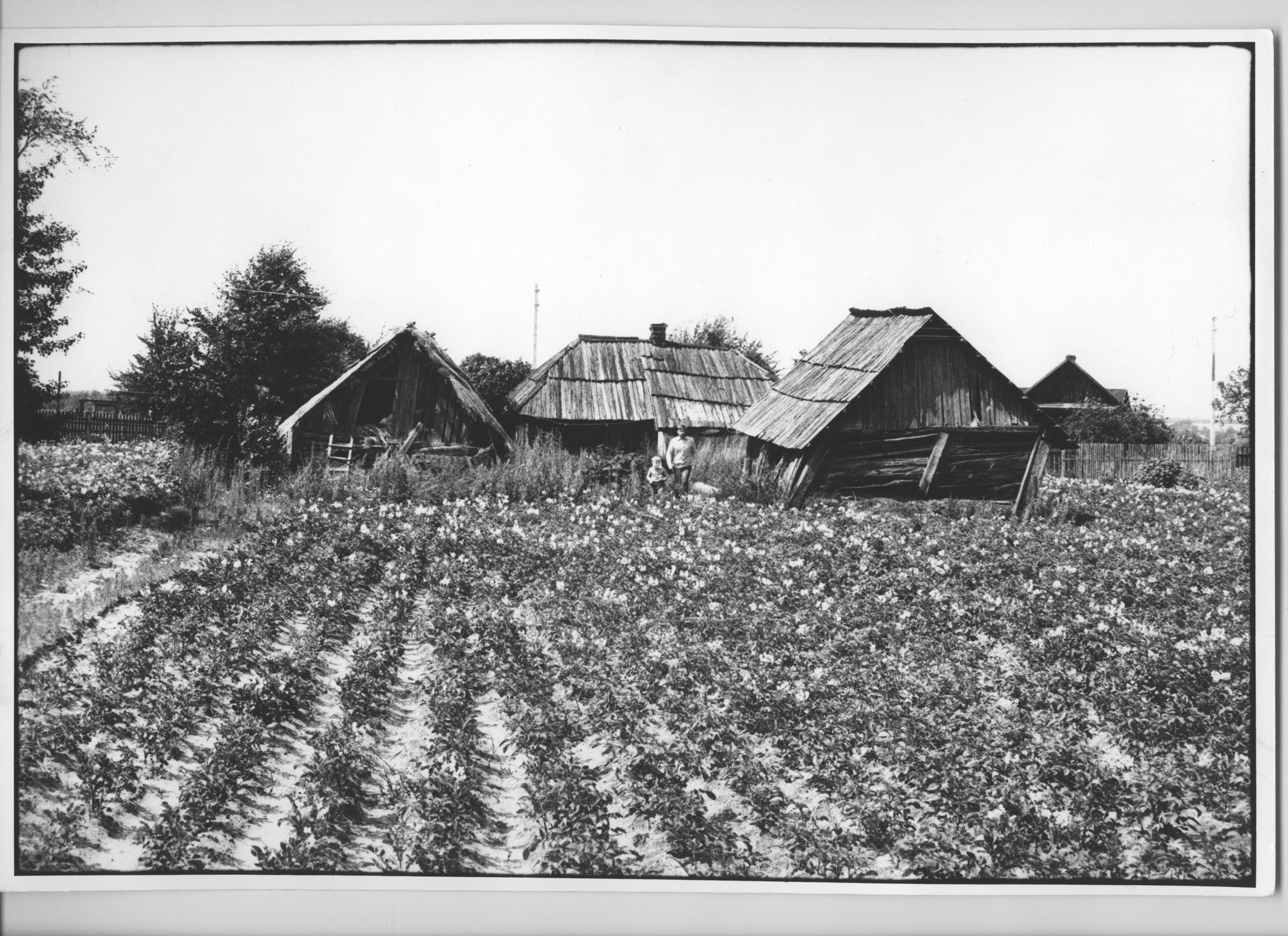

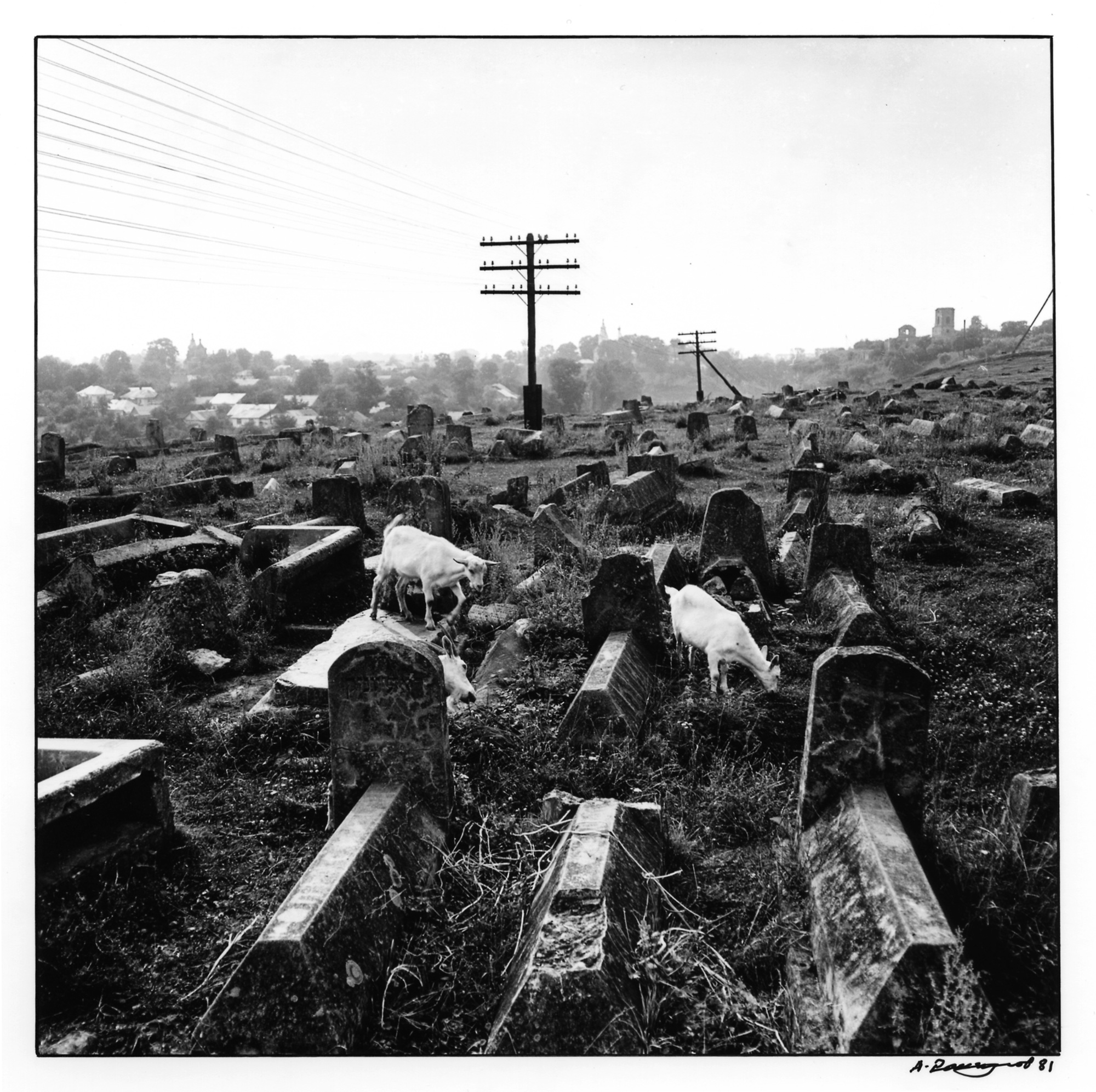

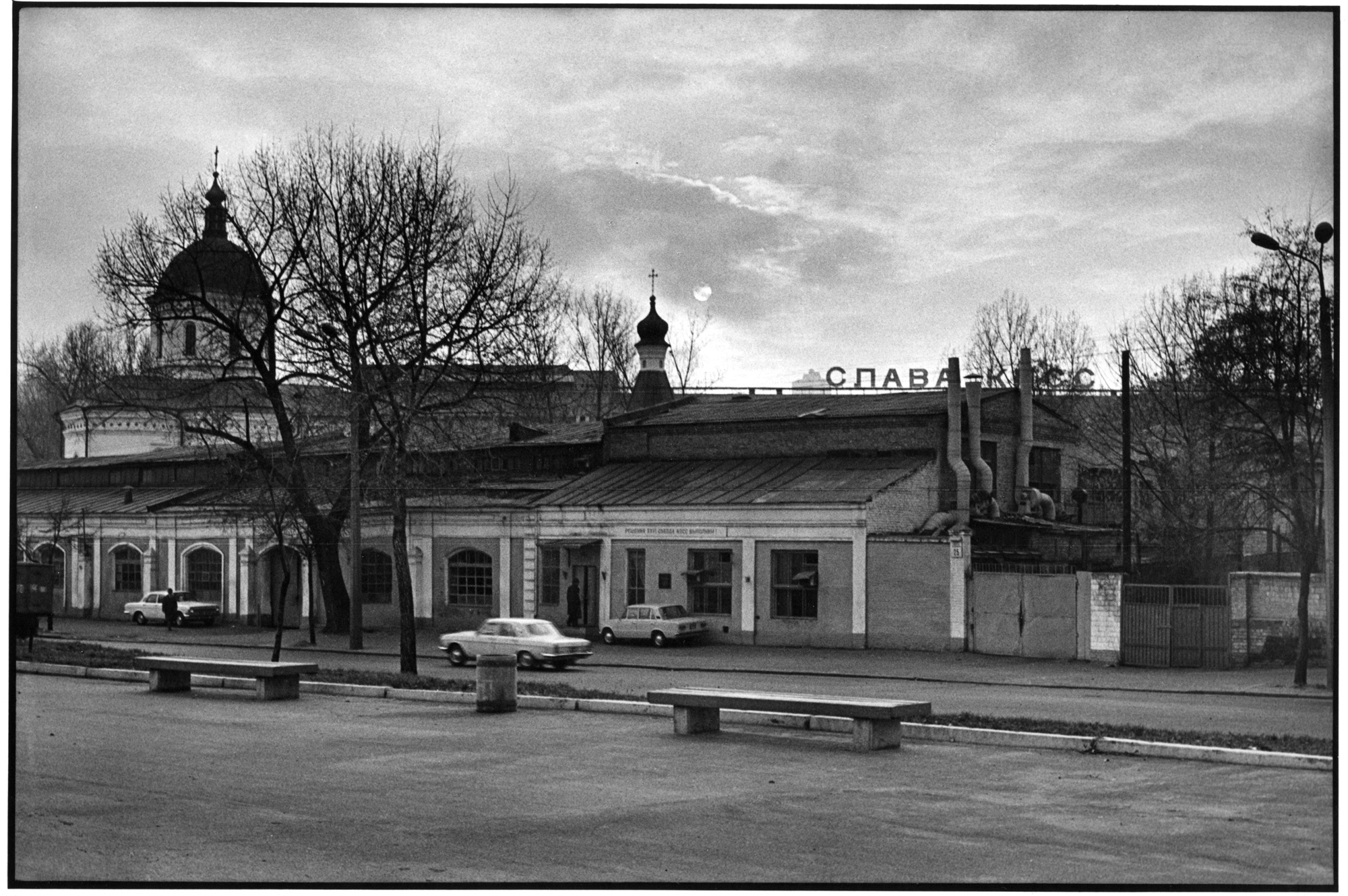

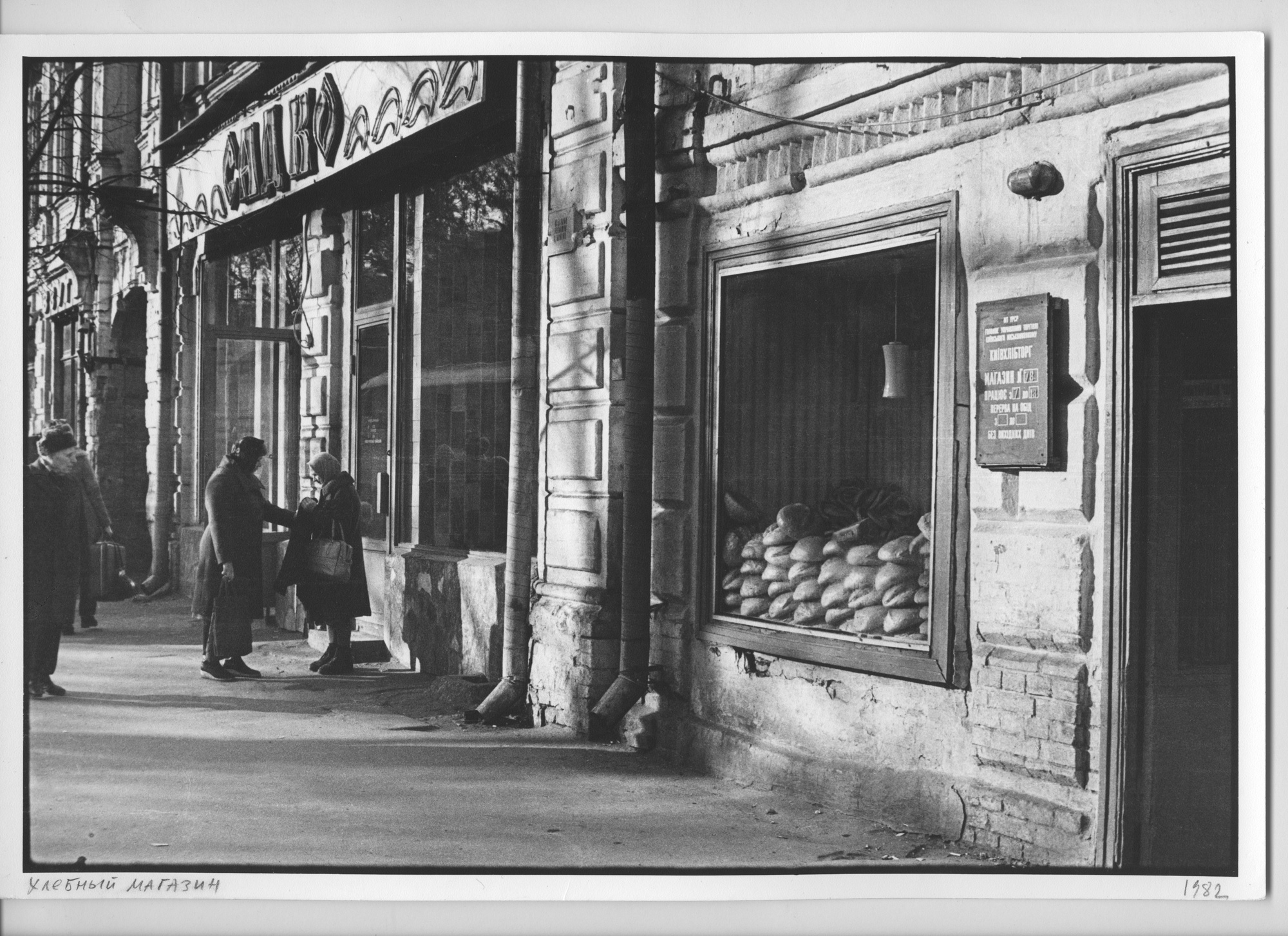

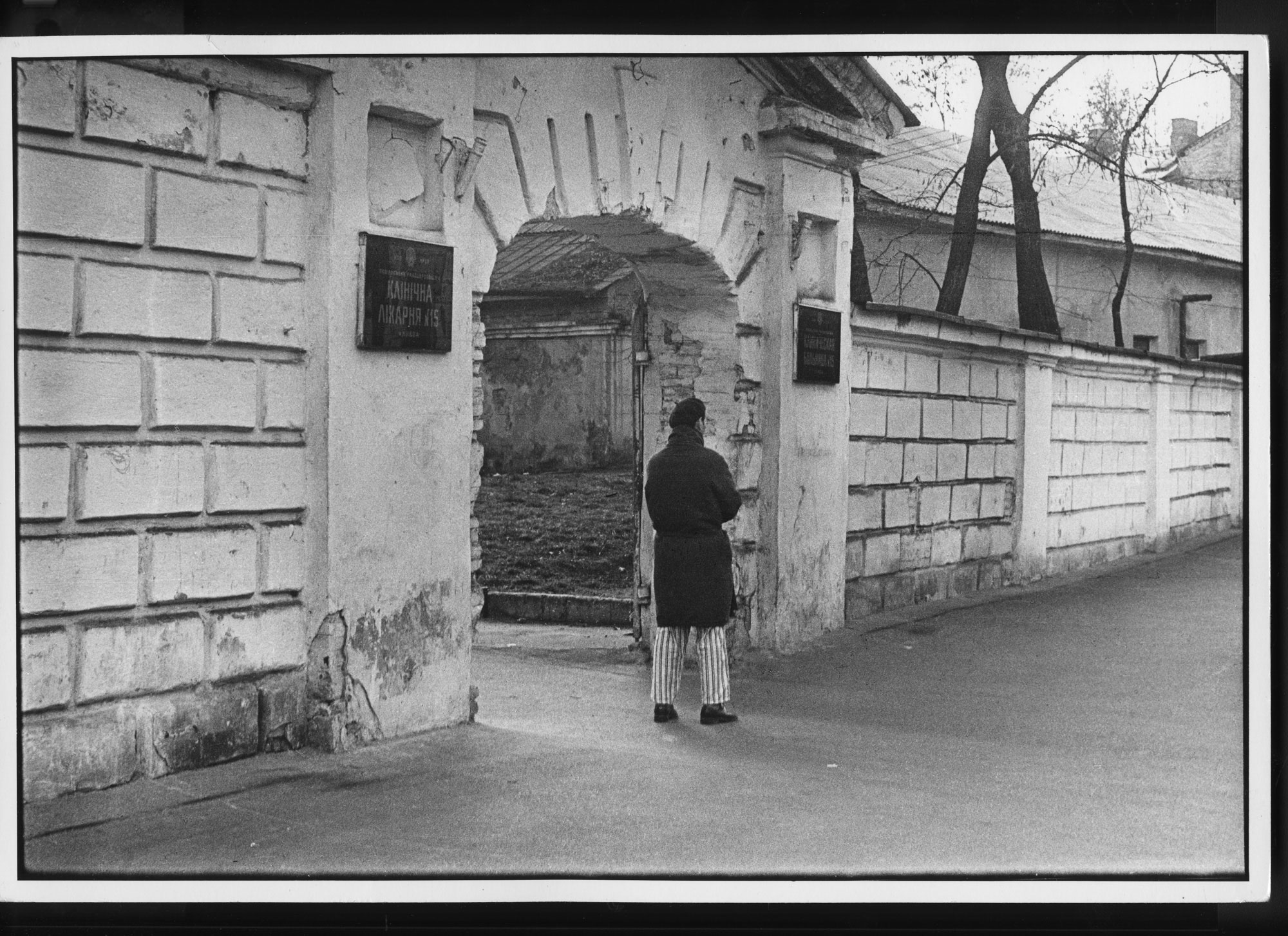

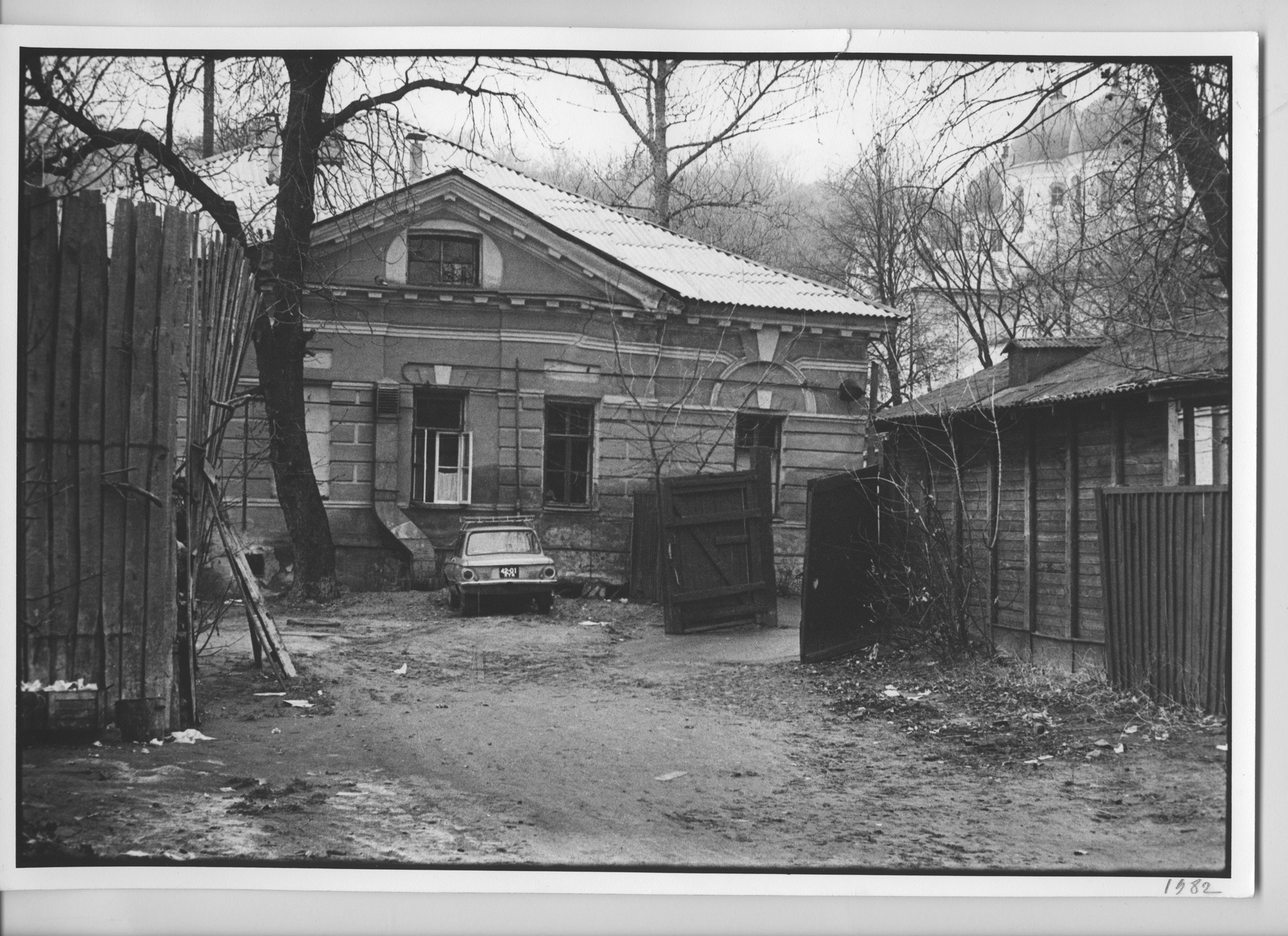

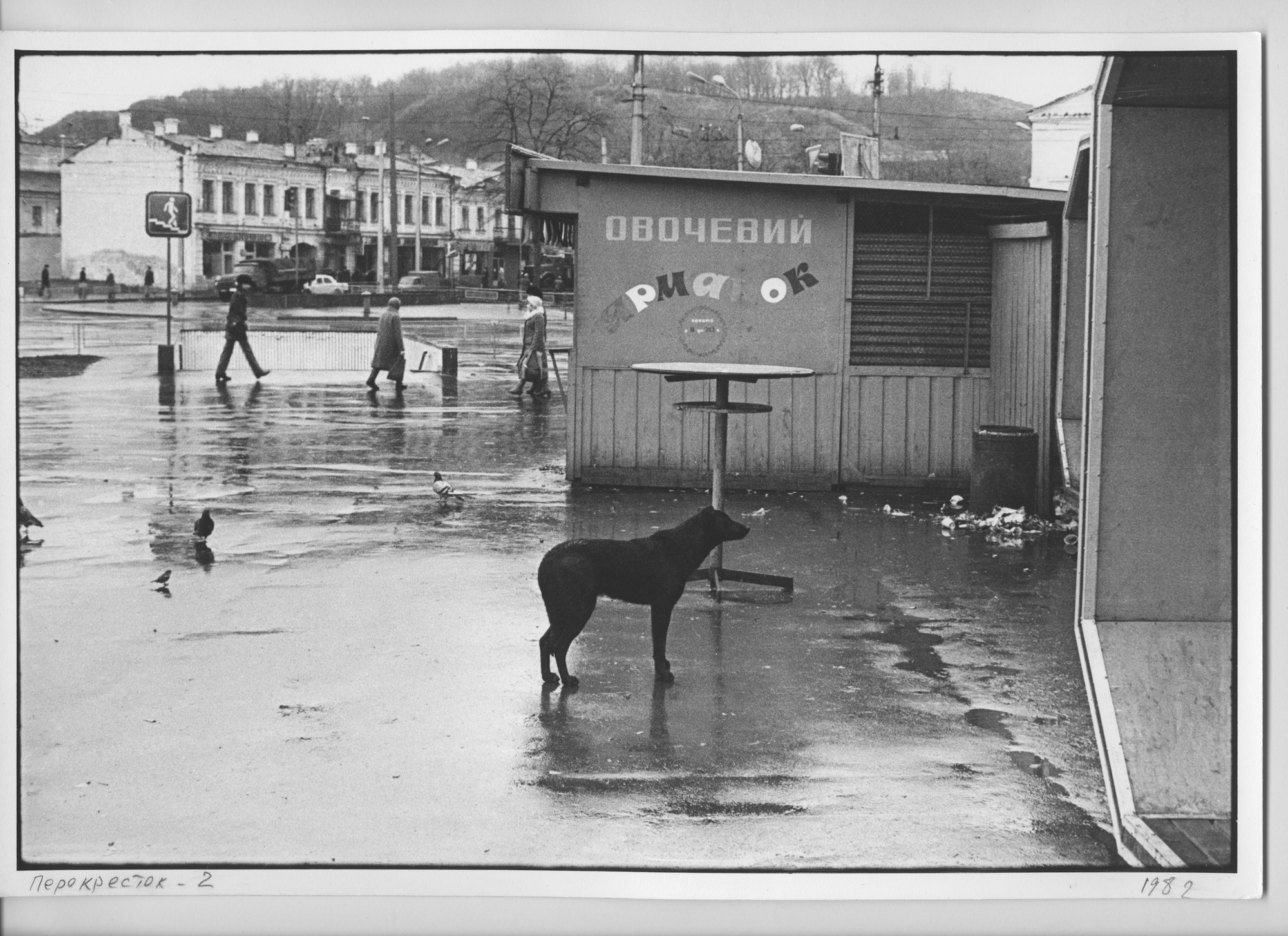

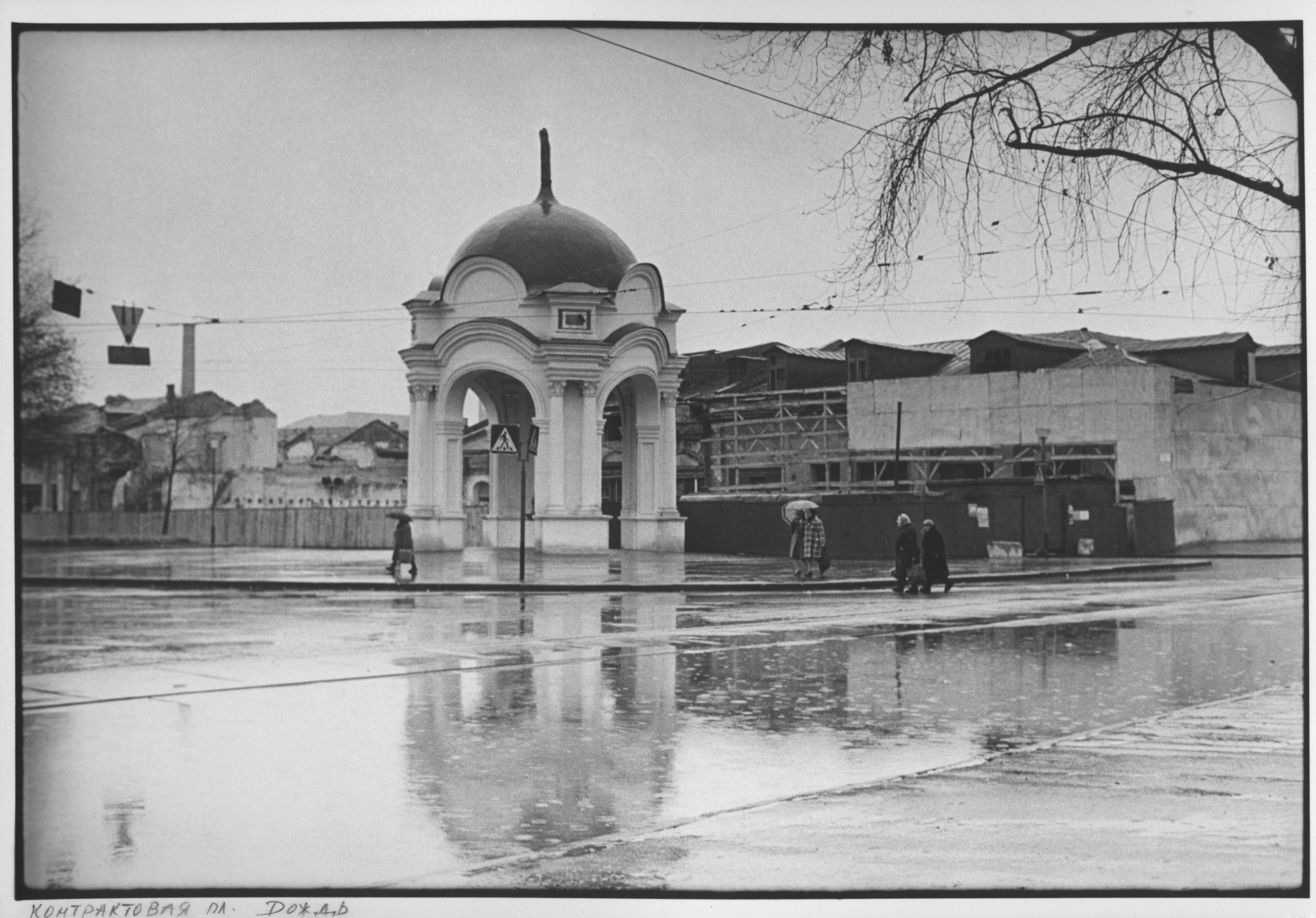

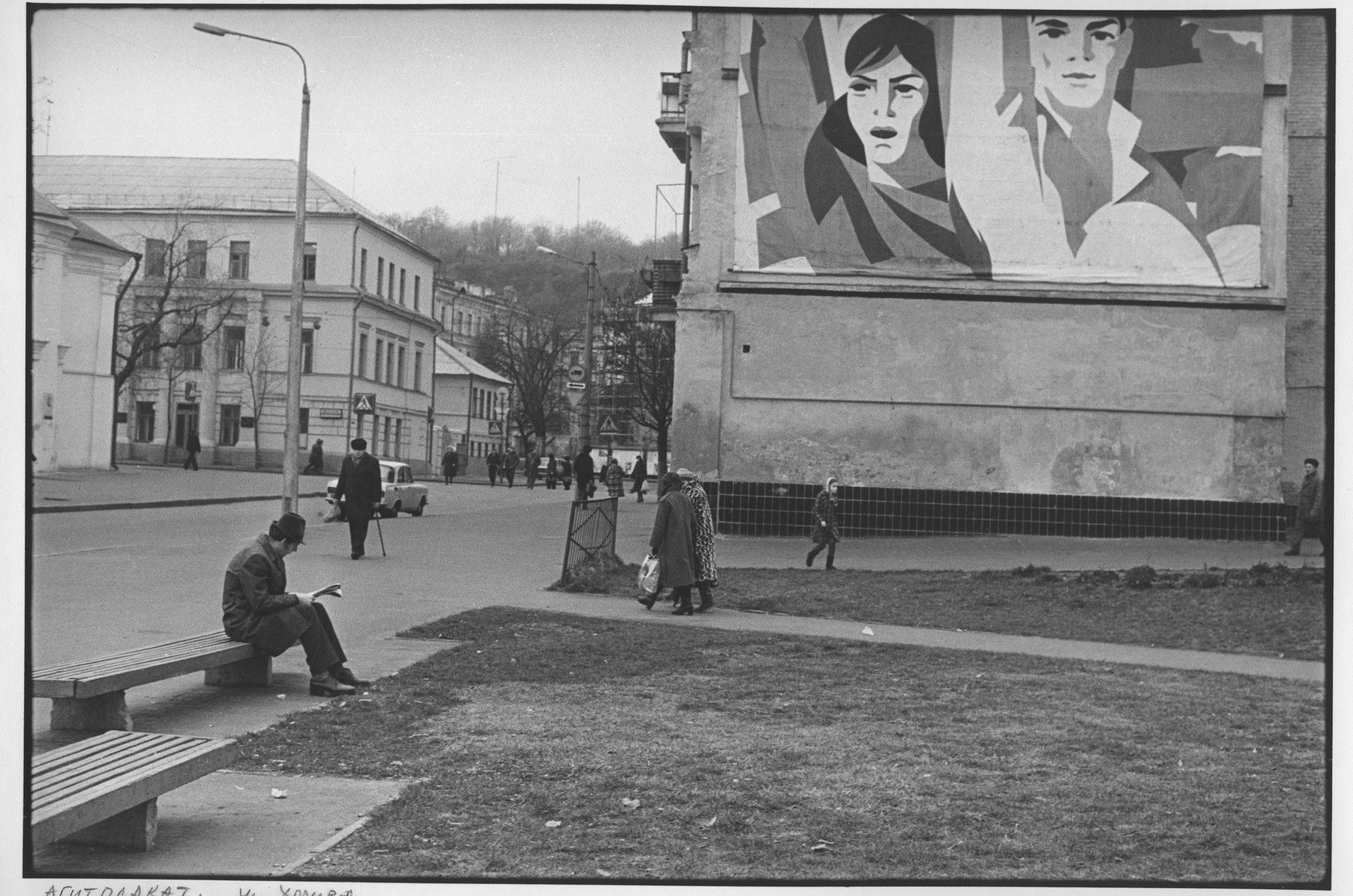

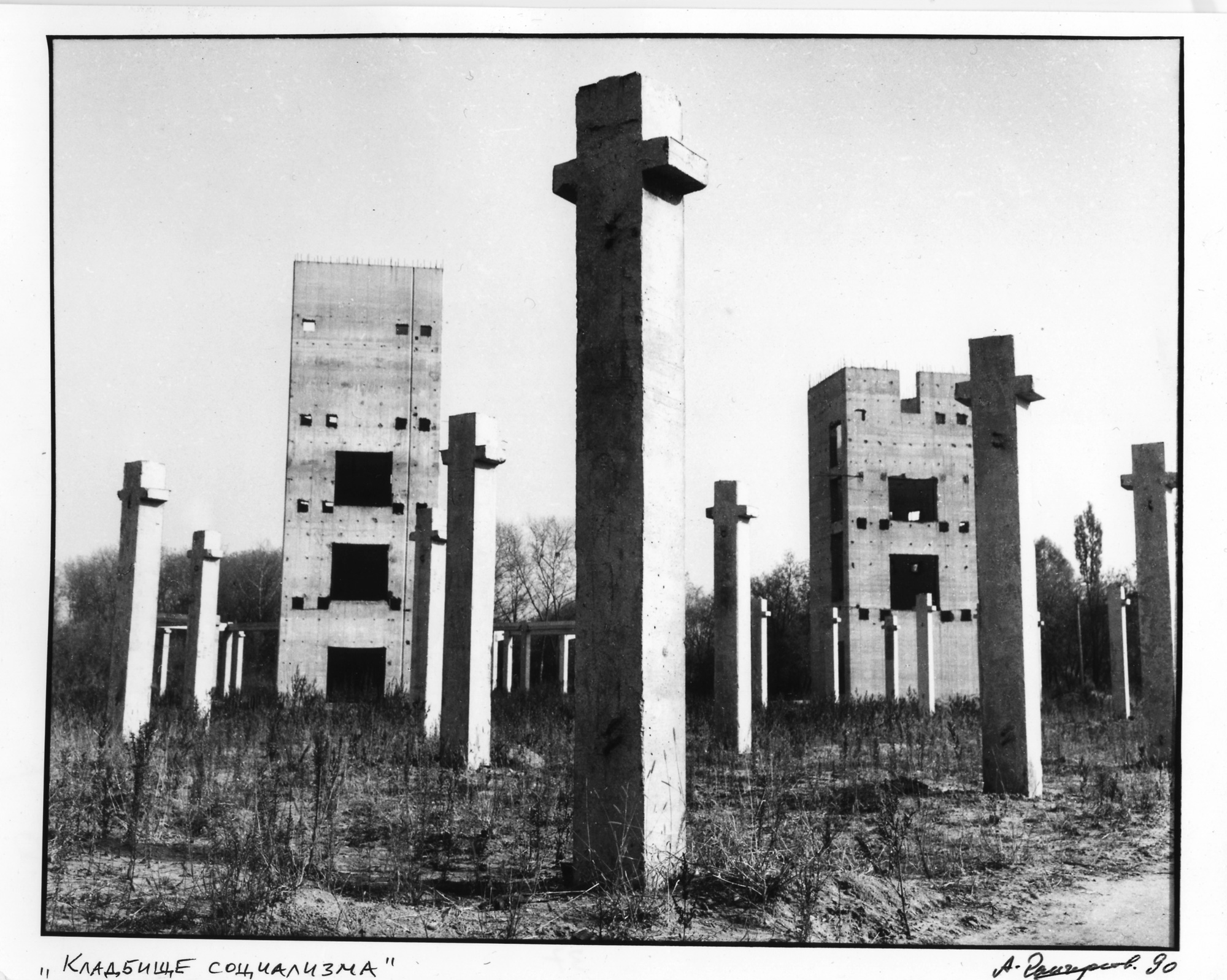

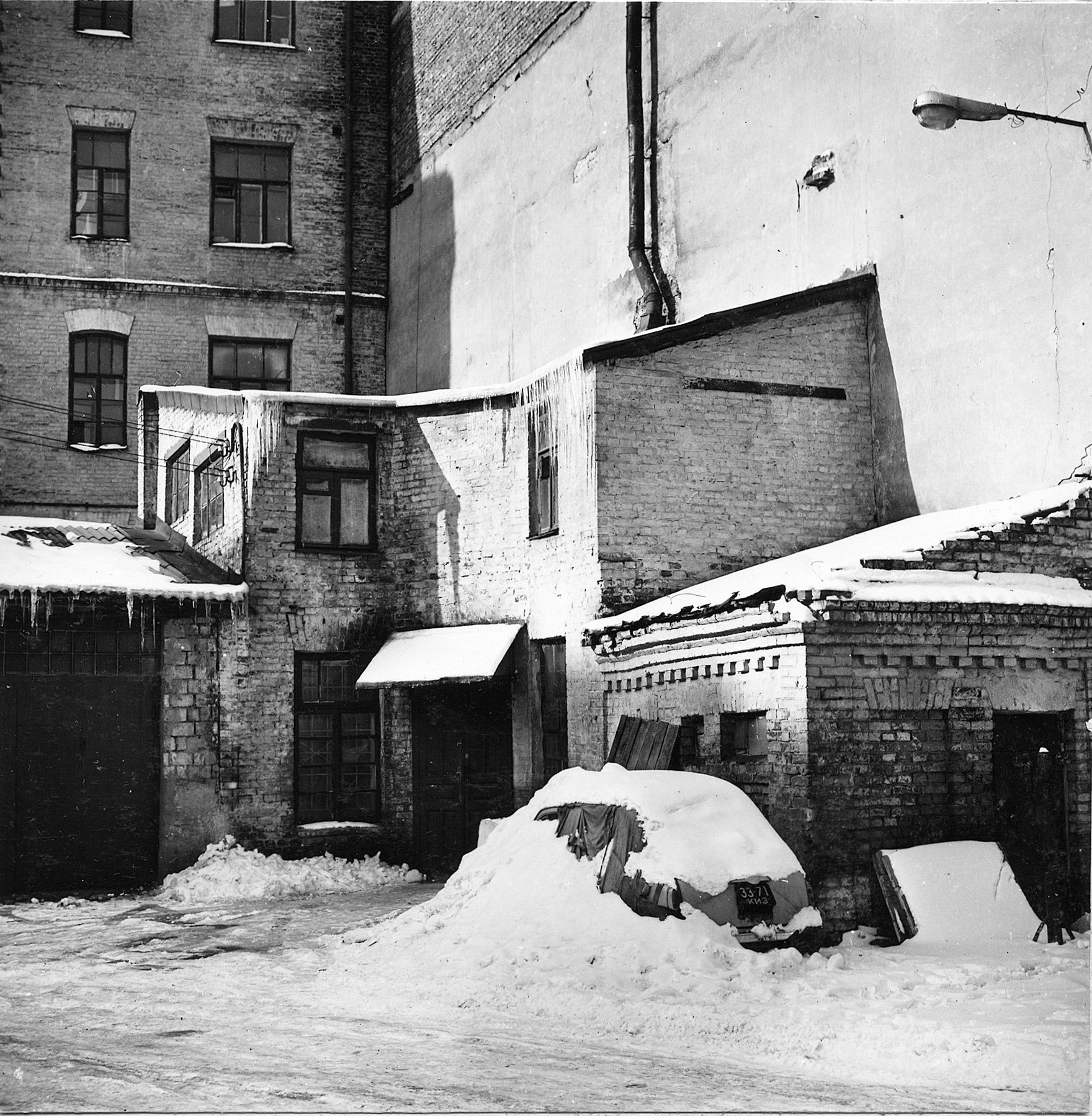

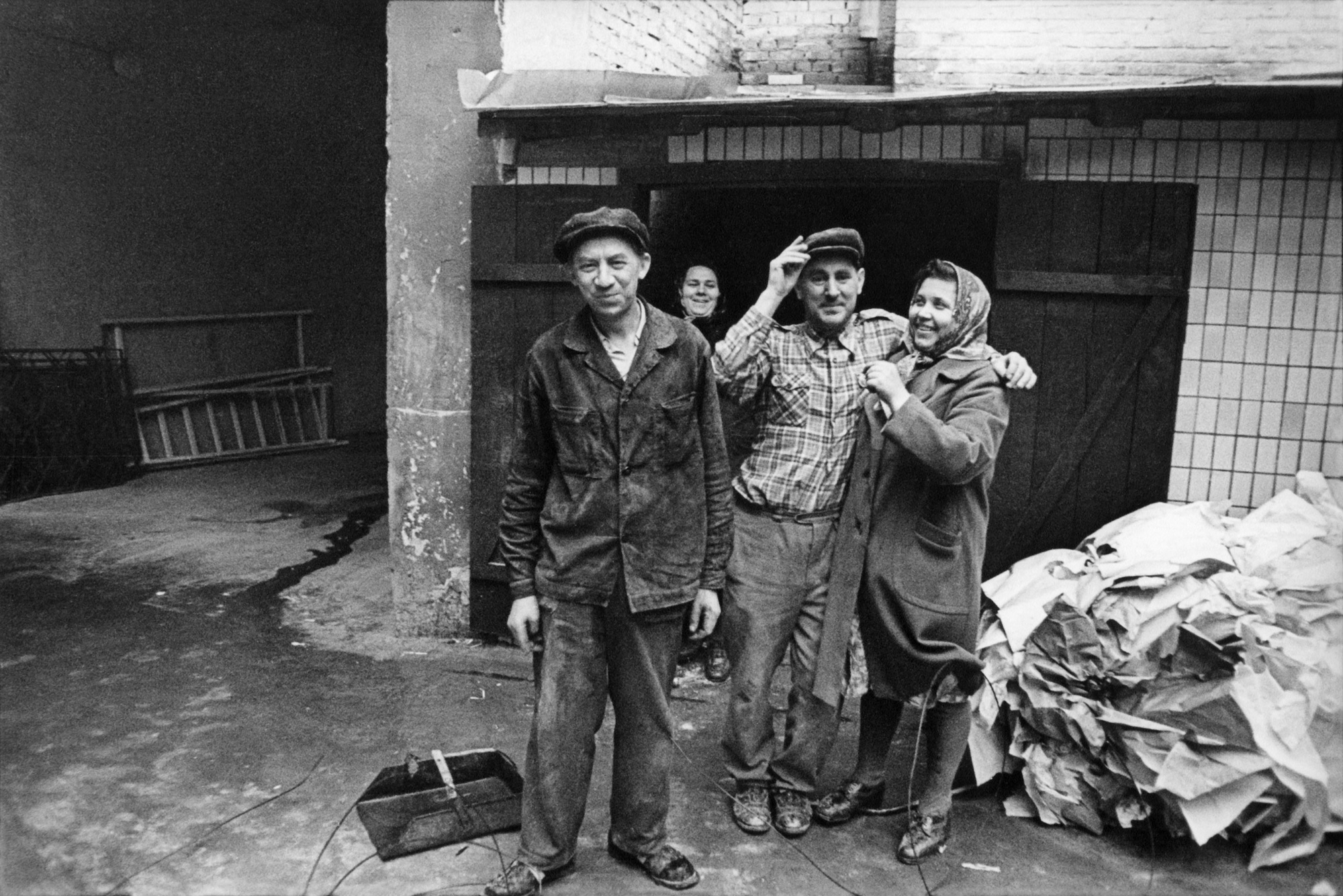

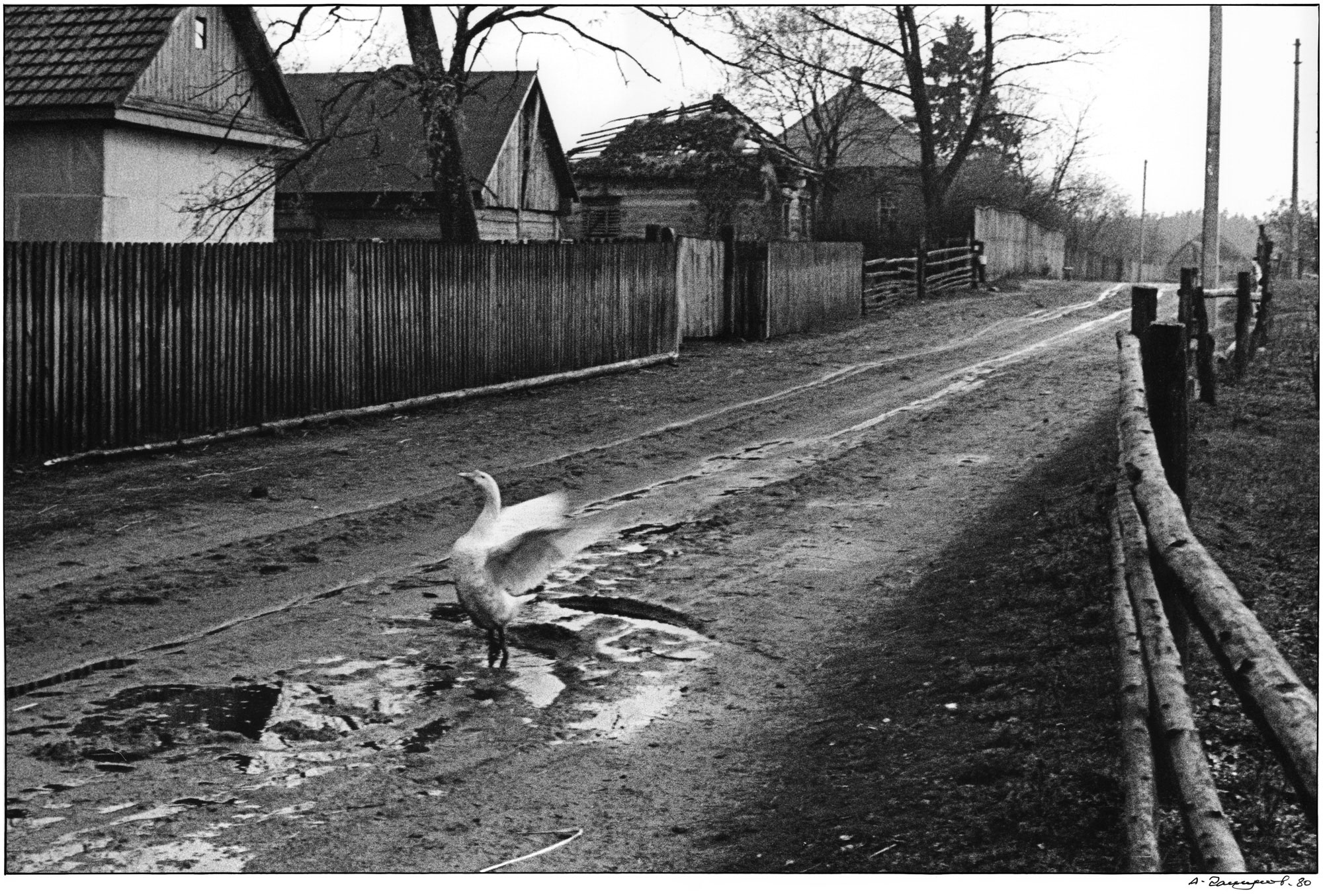

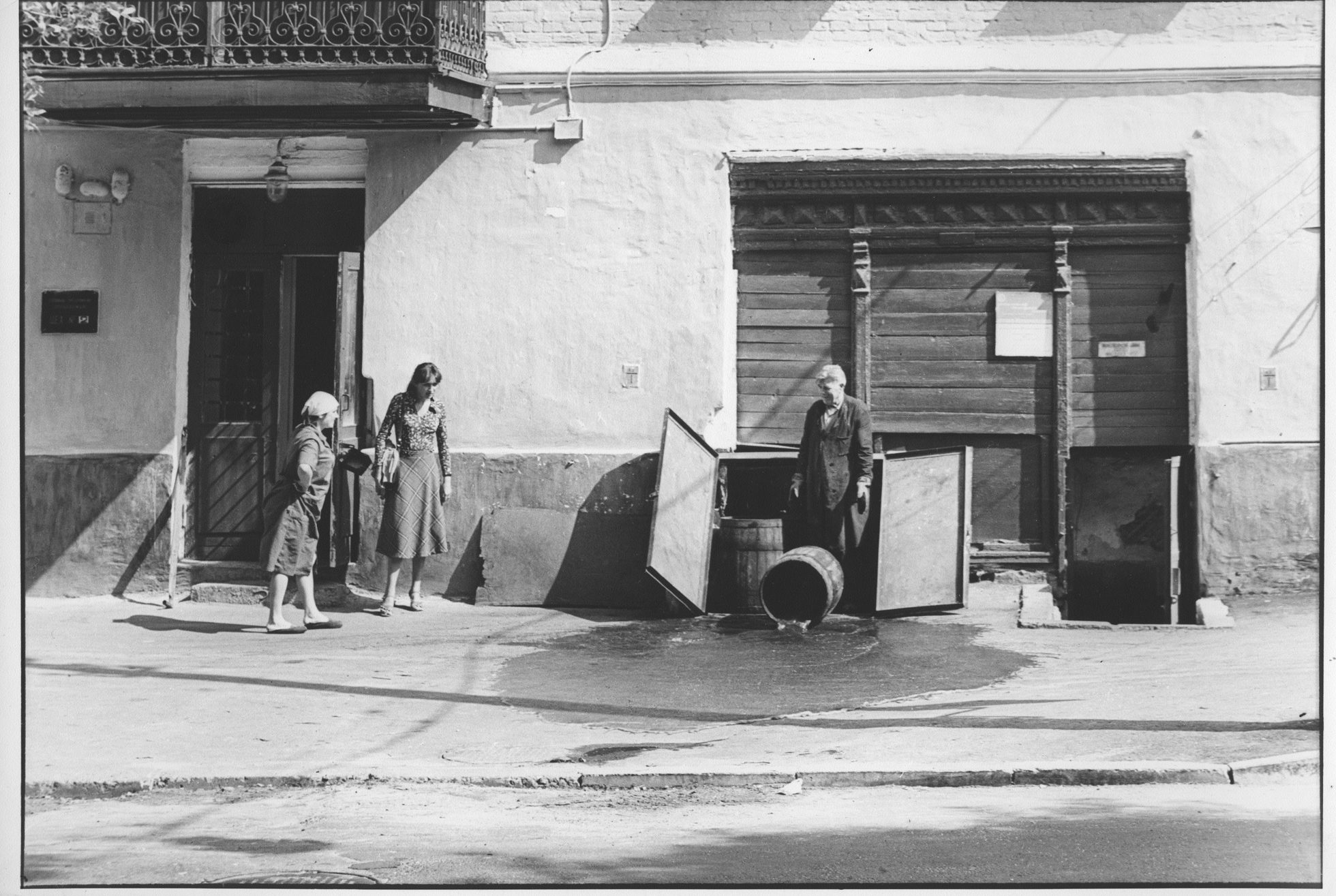

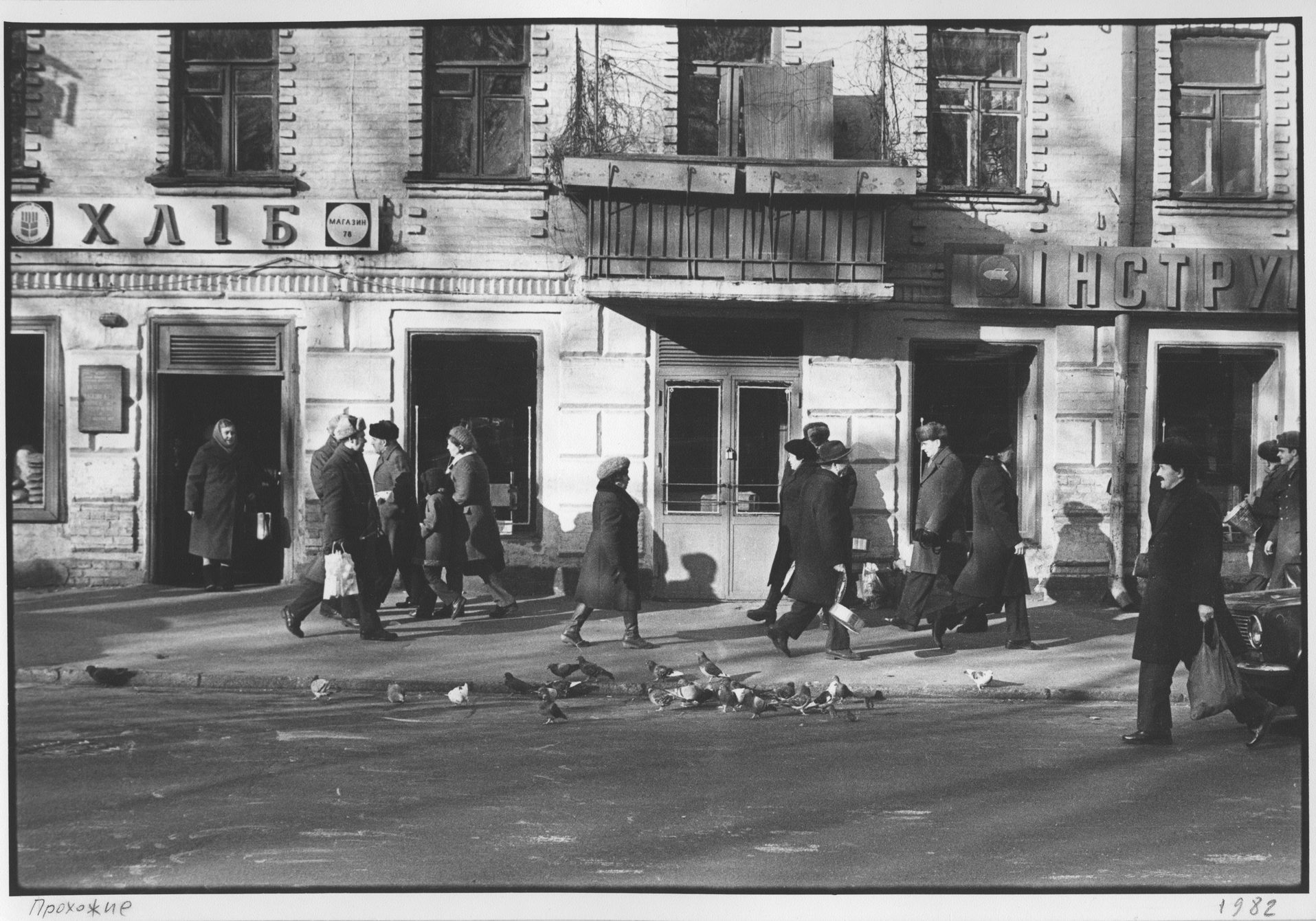

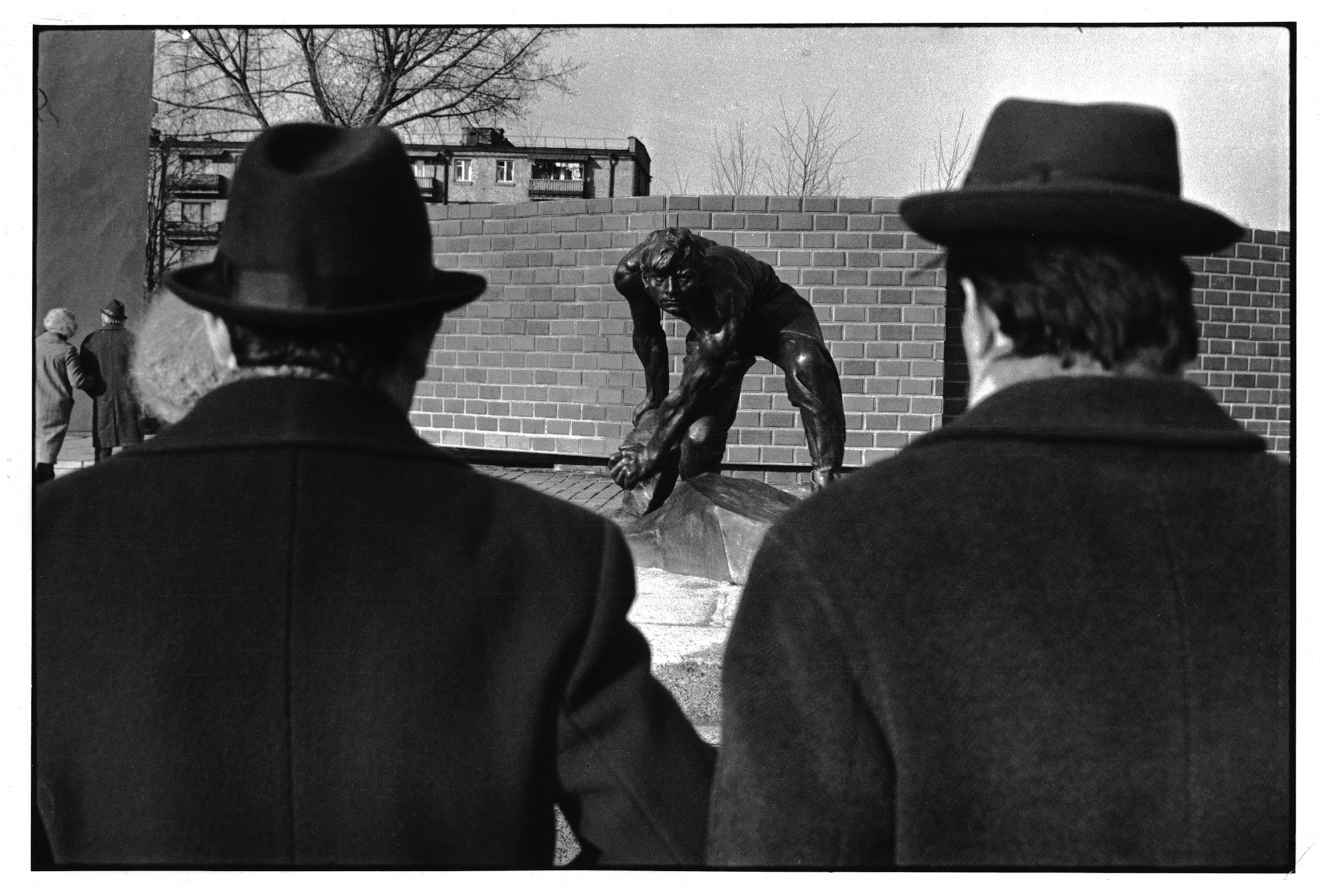

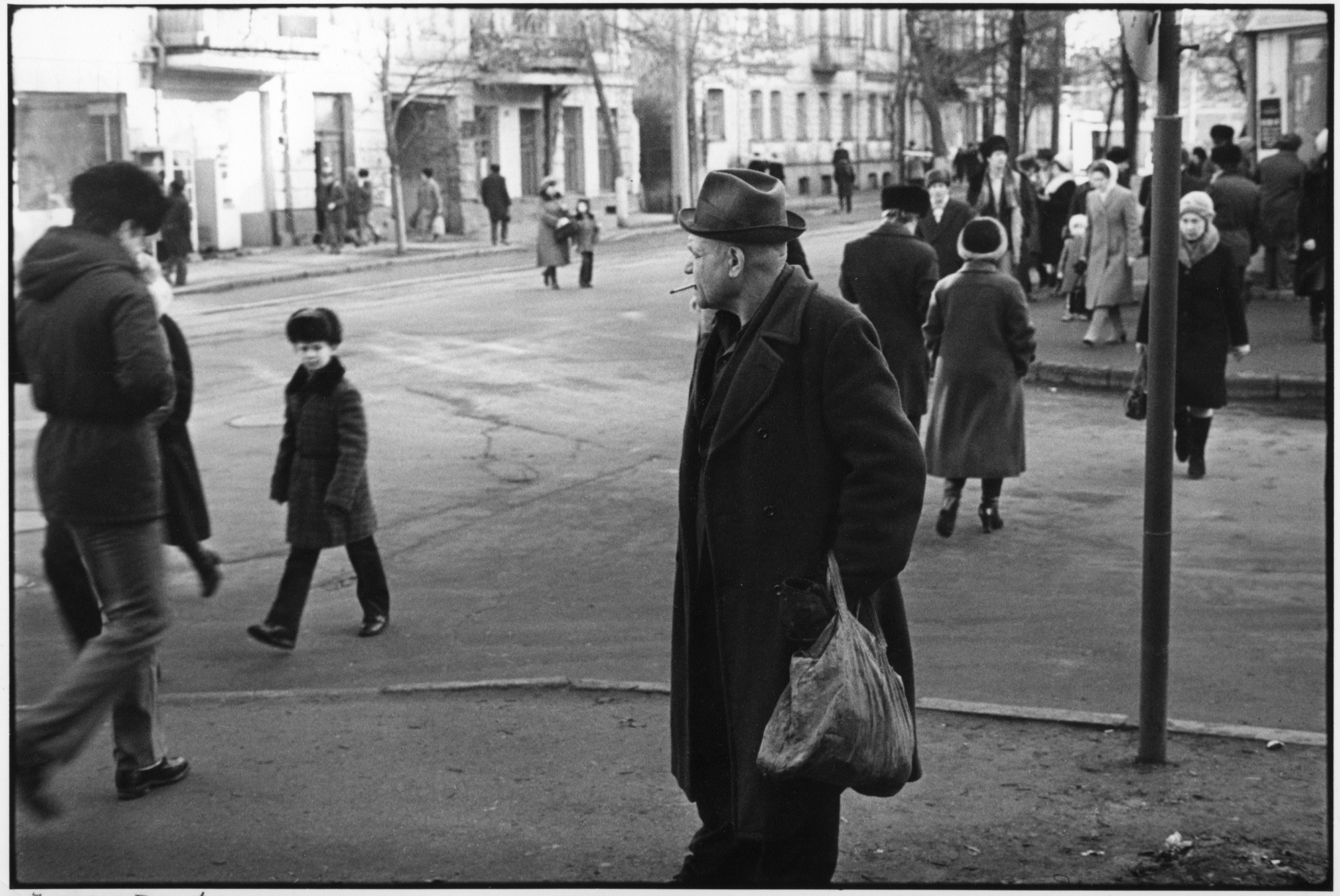

Ranchukov was a street photographer, but he had almost no interest in the aesthetics of street photography — hunting for the moment, looking for the right composition that exists for a split second. He was interested in the typical things, in the things that link people of his time in different cities of Ukraine. Ranchukov painted the picture of Soviet everyday life — dull and inexpressive, even dead: identical grey streets, unsightly clothes, street vendors, puddles, and dirt. In his photographs we see a bitter, hopeless void. Ranchukov doesn’t stop the moment, he documents the time that has already stopped and sticks to the photo film emulsion.

Ranchukov painted the picture of Soviet everyday life — dull and inexpressive, even dead.

Philosopher Vadim Skuratovsky described his work very accurately: “O. Ranchukov’s cycle reproduces the dead historical cycle. That here is running absolutely idle. That is to be more exact imitating that work. Life here froze, it stopped, and in some weird way corresponds to the poetics of photography itself.”

Oleksandr shot at eye level — the passerby outlook — and didn’t acknowledge color photography: “Color provides the superficial look on the object. Today, a person may be wearing a red shirt, and tomorrow they may be wearing a green shirt. You can paint a building brown today, and green tomorrow… You can’t grasp the object in color. It is defined by volume and texture. Color distracts, and a black-and-white photograph helps reveal the essence of the object that I photograph.”

Colleagues didn’t always understand why Ranchukov documents ‘bland nothing.’ You can’t boast this work on contests or receive a gold medal at the exhibition. The photographer himself didn’t believe that the work will be valued and be in demand while he is alive. He deliberately took photographs ‘for himself’ — but he gladly showed them to everyone who was willing to look. “If a photograph is a success, somebody else might be interested in it. This way, photography is my way of communication with the world, with other people.”

Colleagues didn’t always understand why Ranchukov documents ‘bland nothing.’

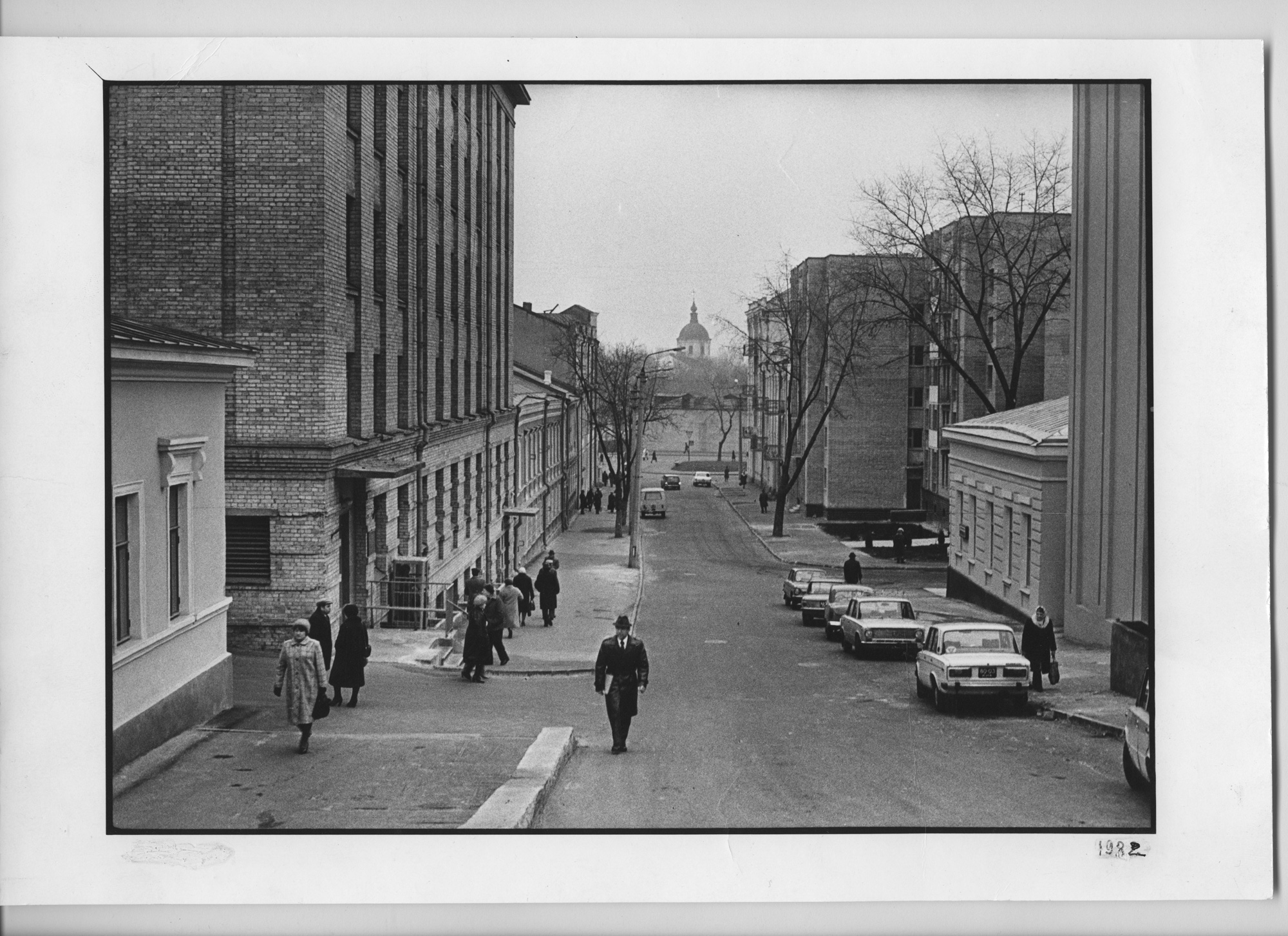

He confessed to me that he works as a chronicler: later, after many decades, these black-and-white prints will complement the story of the sad end of the USSR, the dull streets of the city showing its decay very well. Ranchukov believed in the bright future of the country and said that young people who will live in the satisfied, well-fed, and rich Ukraine will be able to see how things were there before with the help of his photographs.

He wanted to show this young generation the faces of Soviet people — in a way very different from how they are presented on posters. Ranchukov inserted the face of the passerby into the environment, not contraposing them, not adding anything, but stating that they are the same: the faces of the passersby look like pedestrian sidewalks, house walls with peeling paint, dark windows with ‘unkind’ looks of muddy glasses. Skuratovsky wrote: “Those faces have sad and difficult thoughts imprinted on them. About their being some kind of eternally doomed to the numb and petrified world?.. Moreover, they, those faces, bear some kind of a gloomy dignity. Dignity of a person who bears his cross along with the pitiful purchase, until the end.”

City, Nature, God

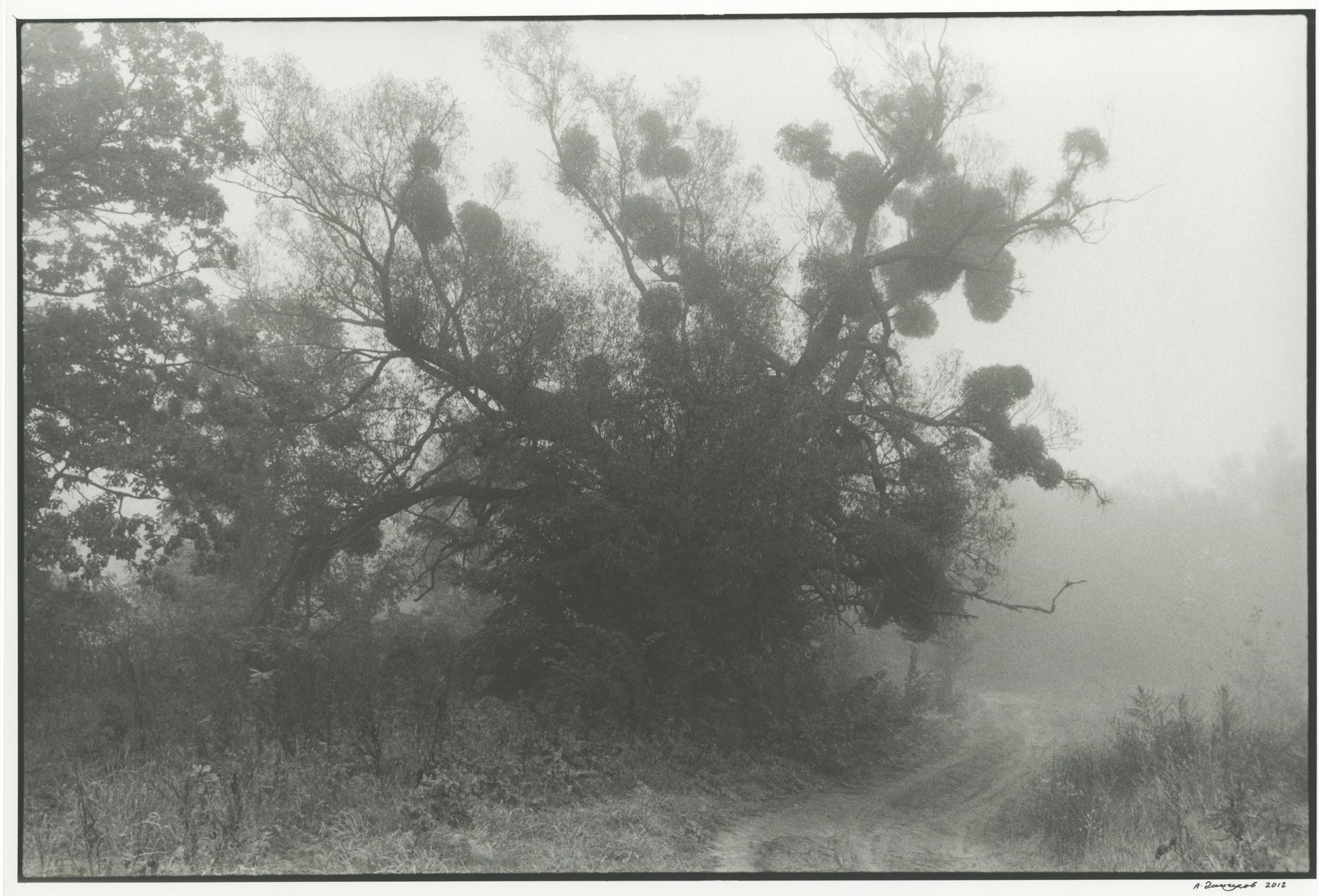

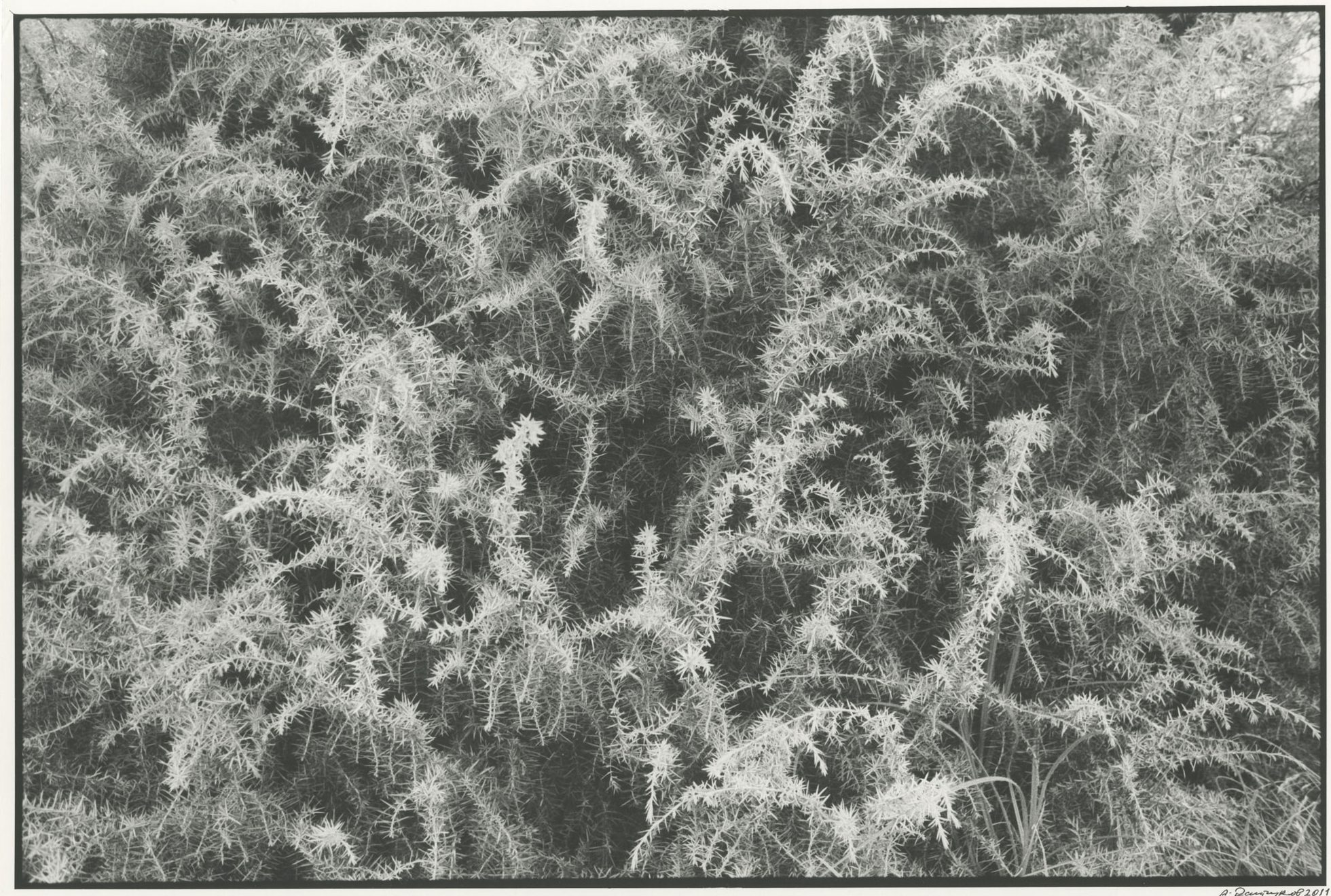

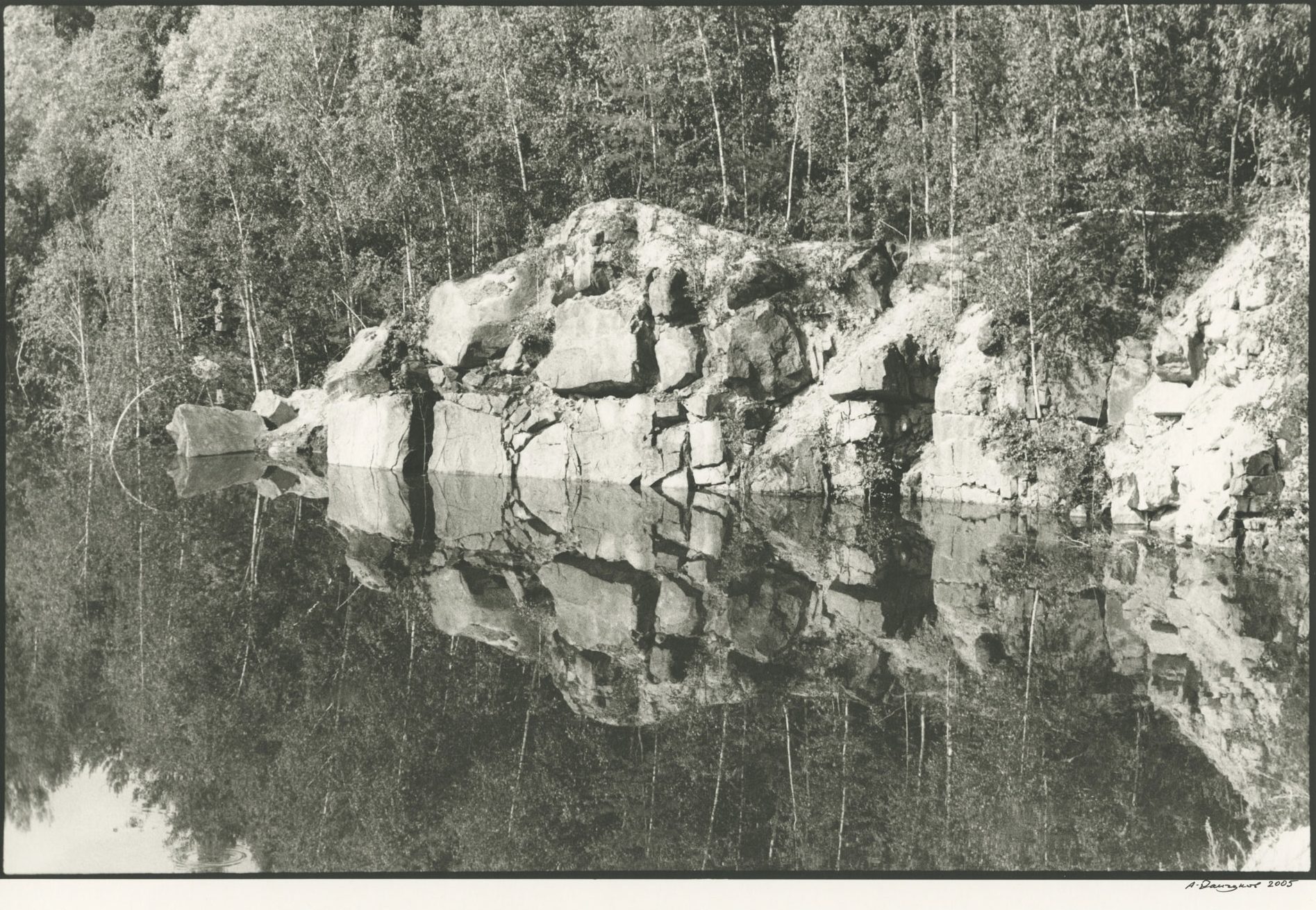

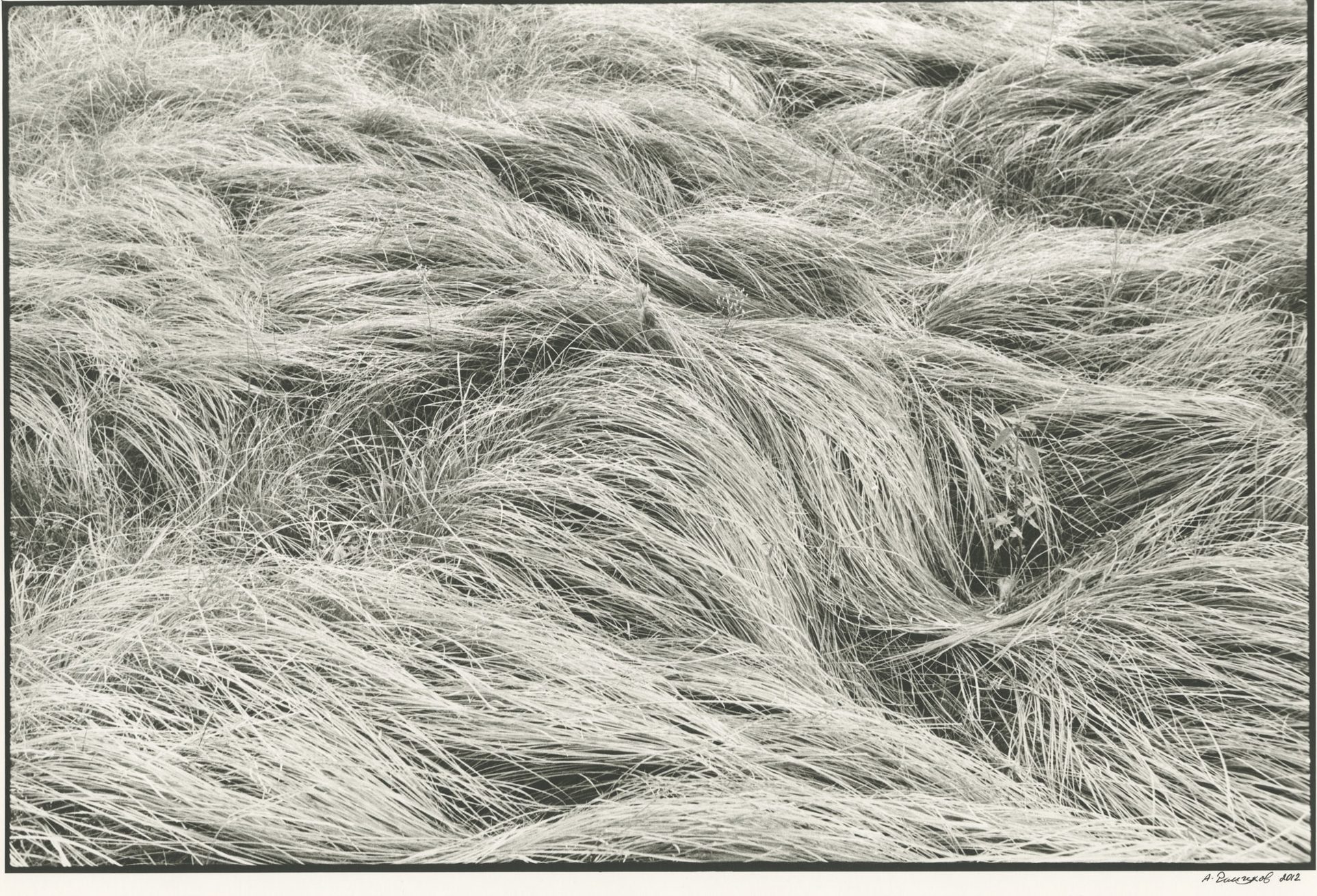

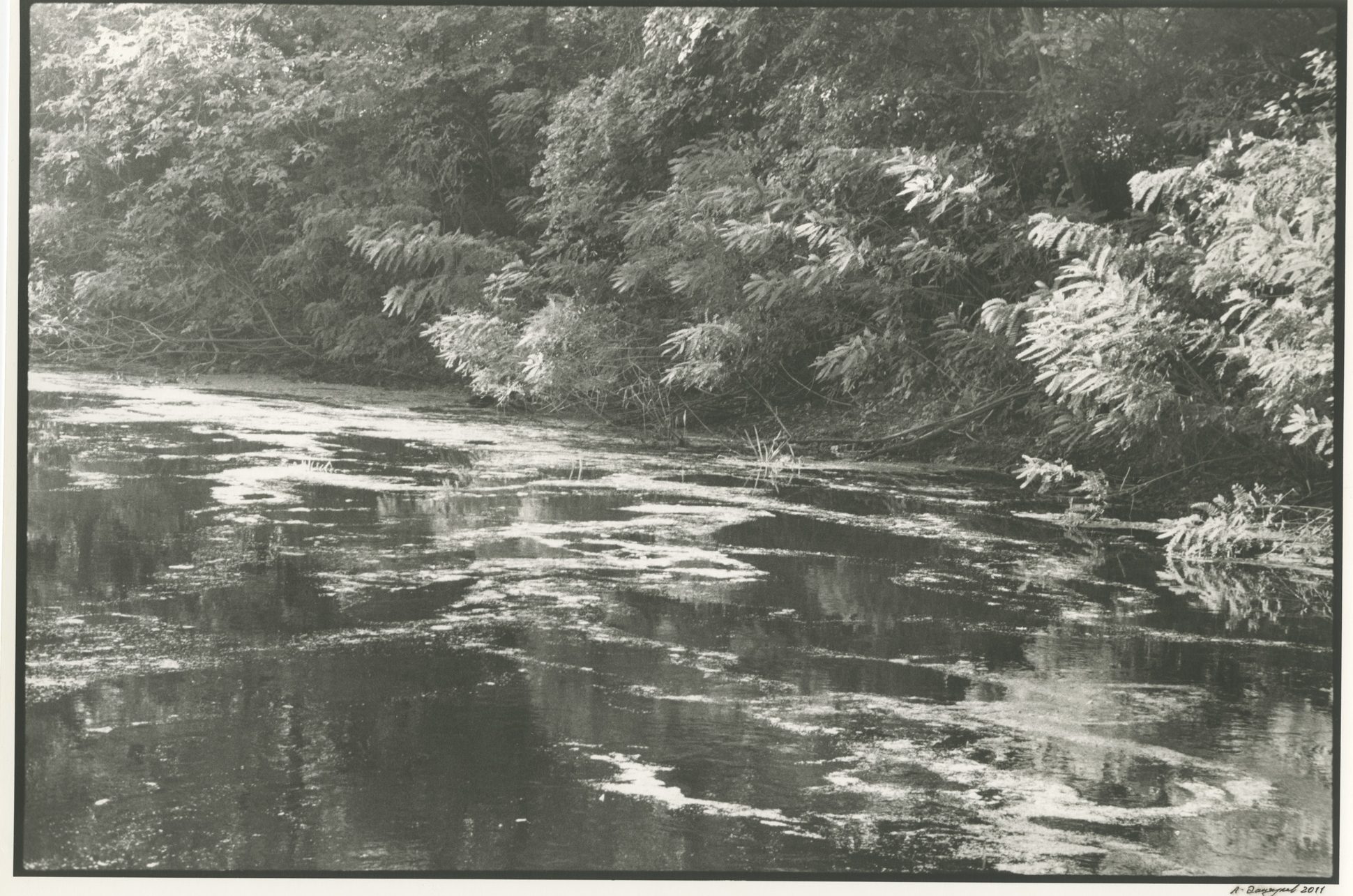

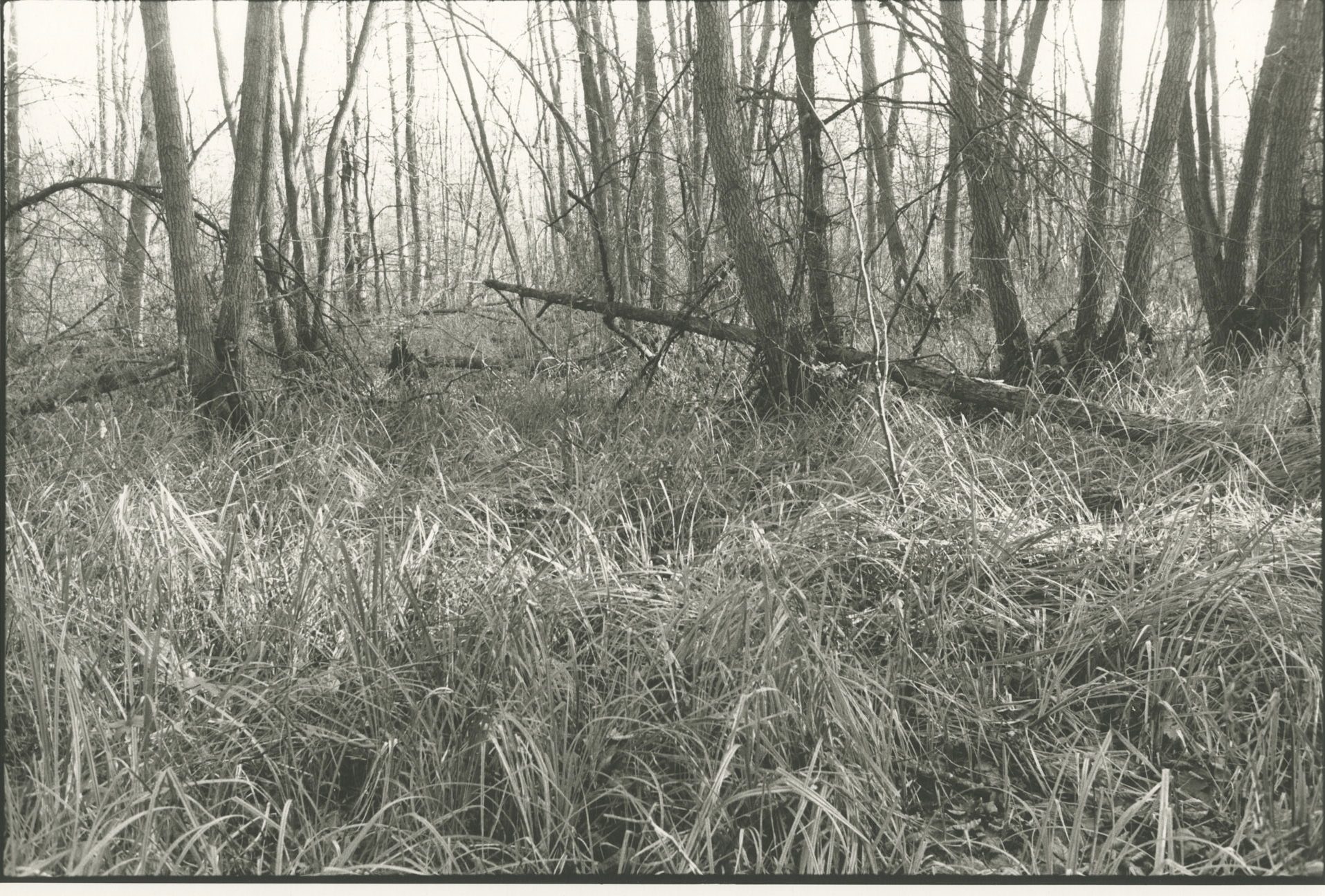

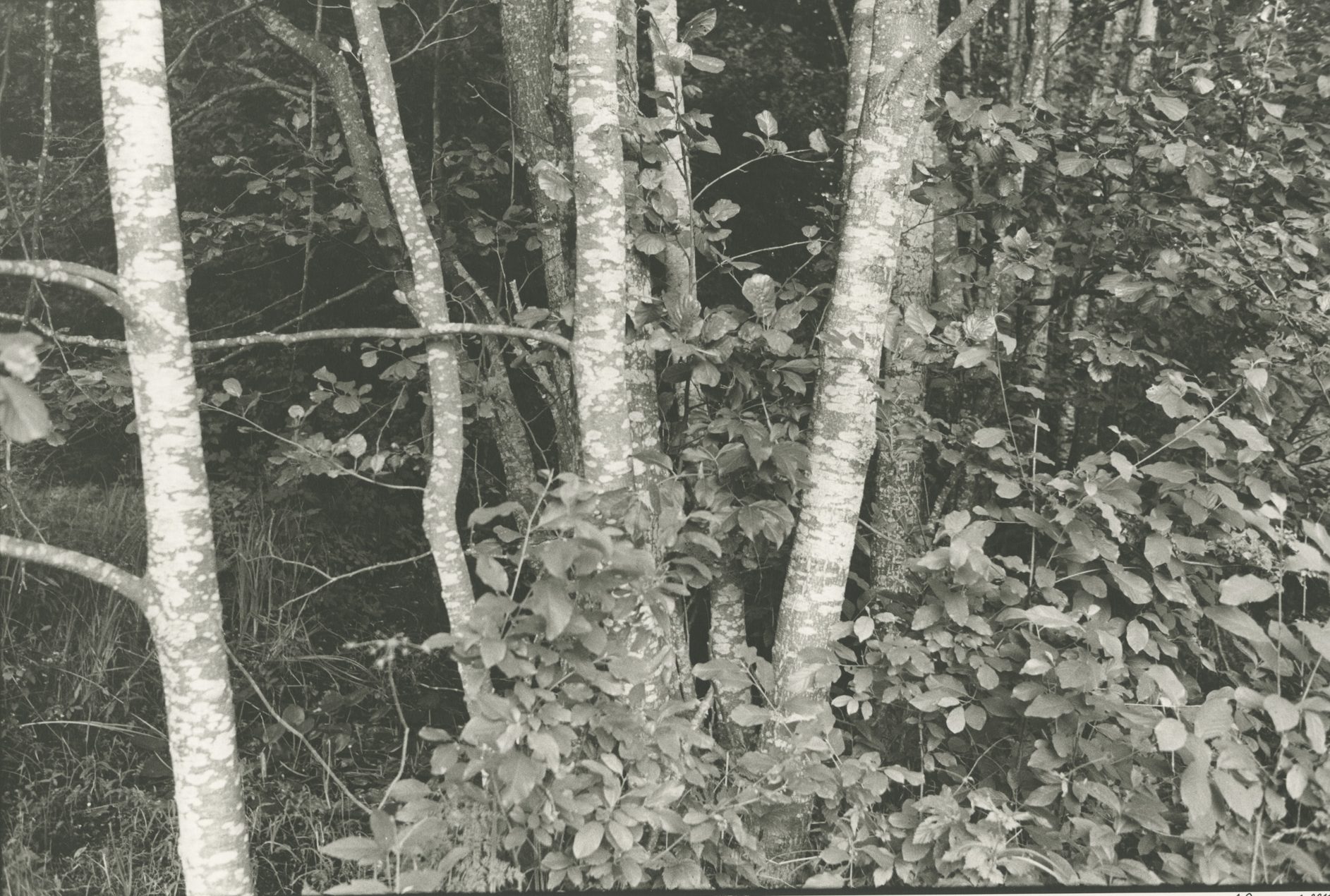

Ranchukov was a man of nature. He took a tent, sat on a bike and went to the forest. He found places where other people didn’t go and lived there for weeks on end — trying to blend into the environment, become a part of it. He didn’t kill mosquitoes that drank his blood. One time, the photographer found a hornet’s nest and a venomous snake rookery near his tent. And they continued living side by side, not troubling each other. “After several days in the forest you get the feeling that you are an inseparable part of everything that surrounds you, meaning the natural world, natural relations devoid of conventions and everything else that gets in our way when we live in the city. I reevaluated the values that I learned under the influence of the generally accepted social norms, points of view, and way of life. I discovered a new worldview, and of course, took some new photographs.”

Oleksandr photographed city landscapes with the same passion: he took pictures of the streets early in the morning, wrapped in fog — wandered the deserted quarters trying to capture something superreal. One time, he photographed a bench by Saint Sophia’s Cathedral and called it “A place to talk to God”: “…you can come and sit on this bench — no one will bother you — and think: about life, about yourself, about something important… For some of us, it is ‘a conversation with God.’ Or meditation.”

He took pictures of the streets early in the morning, wrapped in fog — wandered the deserted quarters trying to capture something superreal.

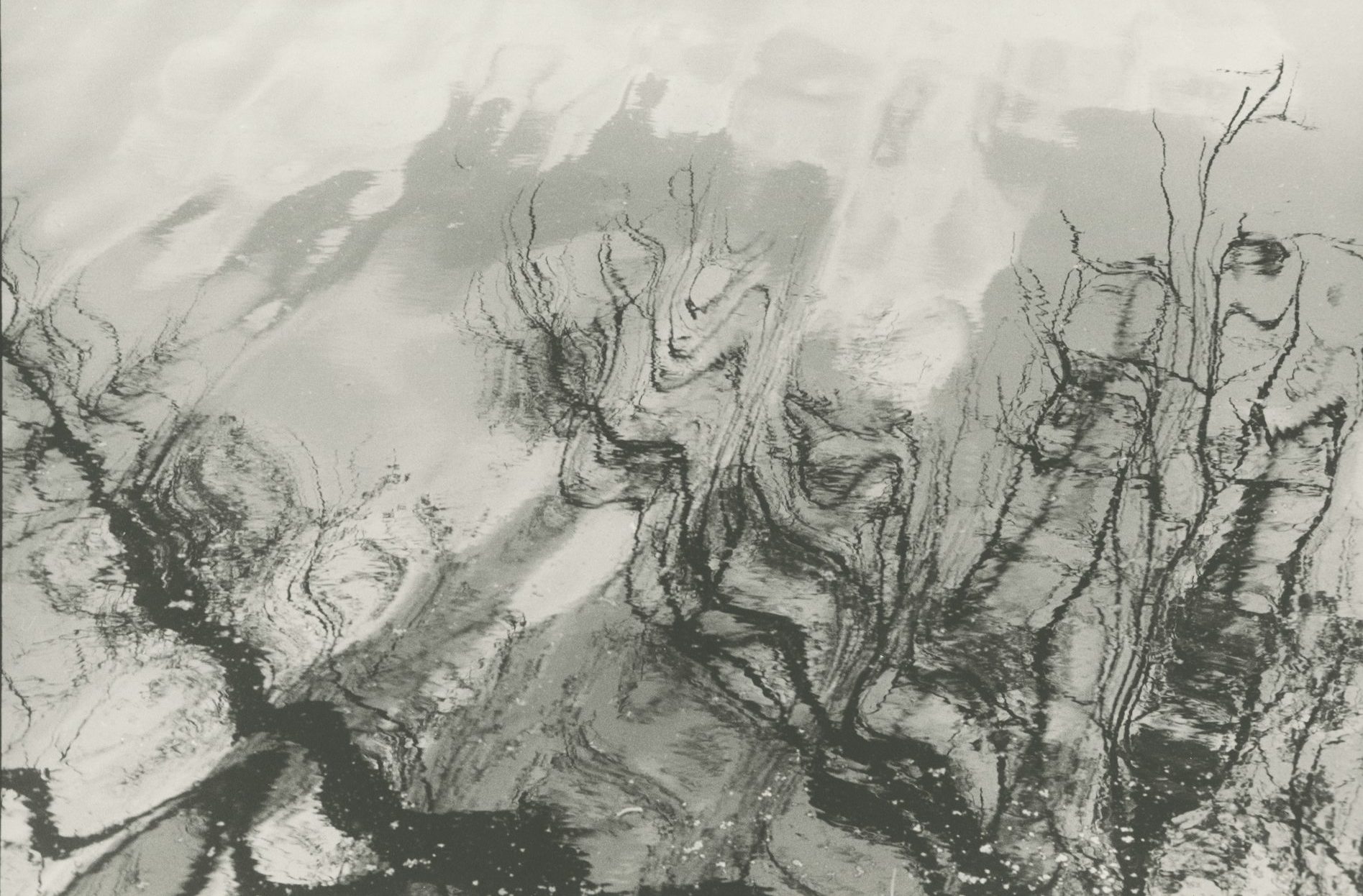

It is interesting how Ranchukov, while being an absolutely non-religious man, has often connected his photographs with the name of God. He was deeply impressed by Borges’ The Writing of the God — one time, he read me aloud the piece that impressed him while we were having a shot of cognac: “I imagined to myself the first morning of time, imagined my god entrusting the message to the living flesh of the jaguars, who would love one another and engender one another endlessly, in caverns, in cane fields, on islands, so that the last men might receive it.” One time, in the texture of tree bark, in the traces left by beetles he saw some signs that reminded letters or hieroglyphs. Atheist Ranchukov photographed them time after time, taking hundreds of photographs — he was deciphering the writing of the God. The eyes of the photographer were shining, he was saying that he almost understands these messages and will soon explain them.

Ranchukov’s landscapes are very complicated: it is not being raptured by fog and sunrise, it is deciphering messages and signs, the game of life and death, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images. For him, they were the reflection of some global processes, impossible to grasp with a human mind. Ranchukov admired Ansel Adams and his ability to convey the greatness of nature — however, Adams was a ‘pop’ photographer: he admired and marveled, but didn’t explore. Ranchukov combined admiration with the understanding of what is hidden, with the offer to the viewer to read the image, find a hidden message and follow it. Ranchukov is a camera light chronicler, creator of subtle intricacies of the image plot of the photograph. His camera worked like a microscope.

Ranchukov’s landscapes are very complicated: it is not being raptured by fog and sunrise, it is deciphering messages and signs, the game of life and death, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images.

A City That Wasn’t

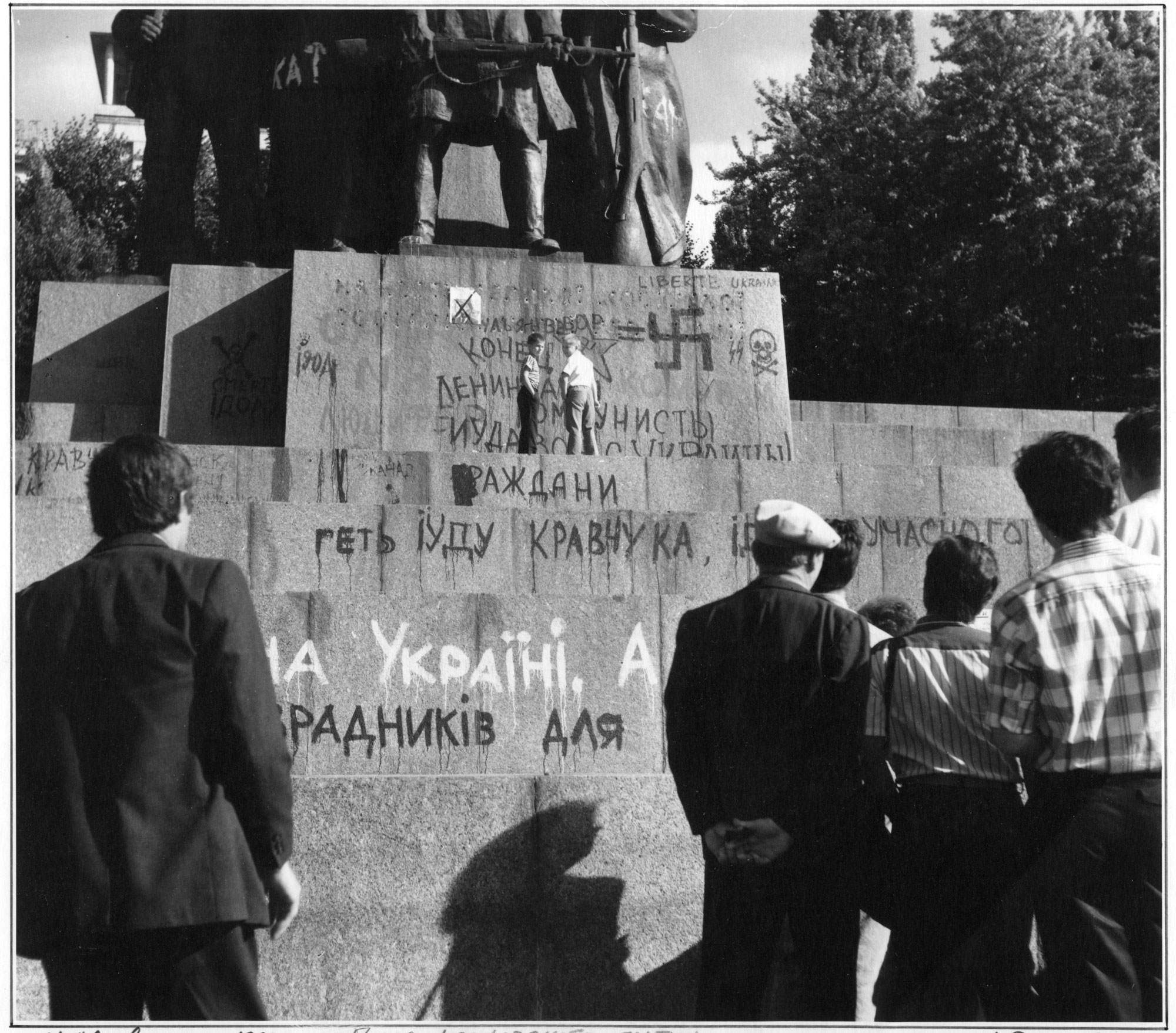

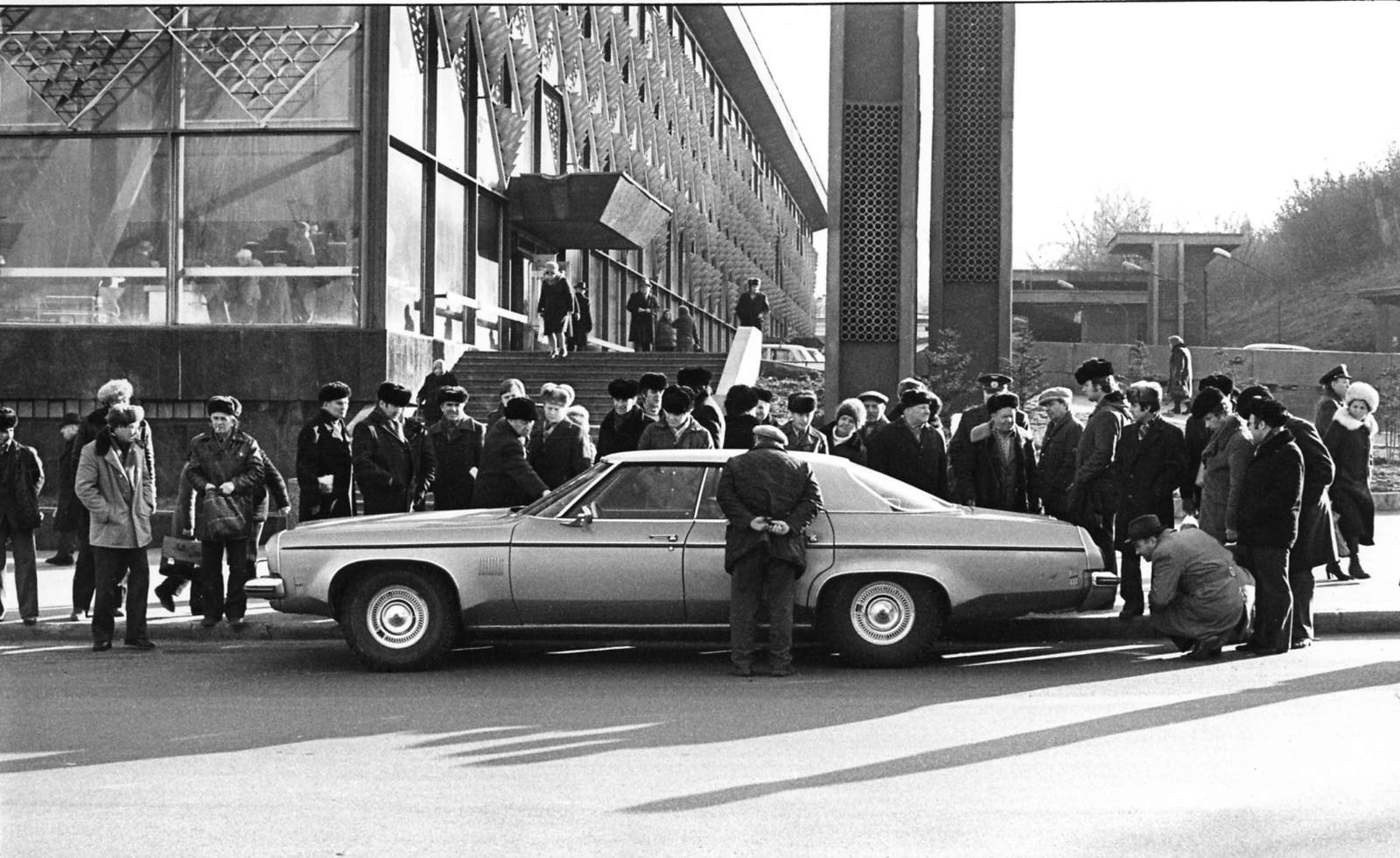

Ranchukov was sometimes himself surprised by what his camera saw, by its sudden sarcasm. When in the early 1990s he was selling his photographs on Andriyivskyi Descent, the one that sold especially well featured a group of poorly dressed Soviet men looking at an American car with surprise and awe. They reminded Australian aborigines who saw the self-moving technical novelty for the first time. Such plots were attractive for customers. Ranchukov was in despair from their tastes and despite the success of his trade soon gave up on it.

Ranchukov was sometimes himself surprised by what his camera saw, by its sudden sarcasm.

Towards the end of his life, he would run away to the forest more and more often — he hid there from the city that was falling into pieces itself and was destroying the idea of harmony in the photographer’s mind. Working at the research institute for theory and history of architecture, Ranchukov took photographs of Kyiv and other cities of Ukraine far and wide: facade details of old buildings, views of the streets and squares. When several years ago I visited him at home, we took a long time to look at Kyiv’s photographs — he noted bitterly: this house isn’t there anymore, this street isn’t there, in this place everything is different.

One time, he showed his photographs to the students of one of Kyiv’s universities: all of them were born in Kyiv and thought that they knew and loved their native city. As they looked at his works, they suddenly asked: what is this city? Ranchukov was astonished: “This city isn’t there anymore, and neither are its citizens.” He gathered the photographs, said goodbye, and stepped outside to smoke. Only one person spoke at Ranchukov’s funeral — it was Oleksandr Gliadelov. He said a short phrase: “The old Kyiv that Ranhukov loved and photographed had died, and Ranchukov went together with it.”

However, he left behind an enormous photographic archive — and I wonder, what it’s fate will be.

New and best