“The Post-War Temporary Housing Wasn’t Much Different from Concentration Camps”: A Historian on Rotterdam’s Reconstruction after World War 2

The Netherlands surrendered with the destruction of Rotterdam by the German air forces in 1940. Having signed the capitulation, the Dutch hurried to rebuild Rotterdam. The reconstruction aimed to turn what used to be an industrial city into a modern megapolis. Local authorities had to sacrifice historical architecture and the rights of certain social strata to succeed, though.

Dutch scientist, Dr. Stefan Couperus, studies the history of city planning and politics in Western Europe. In his interview for Bird in Flight, he explained why the Dutch still celebrate the anniversaries of the Rotterdam reconstruction but prefer to keep some things about it to themselves.

Judging by your articles, you are studying city policing and planning of the 1920s–1970s. Why this period?

I also specialize in Western Europe. I am interested in everything that has to do with the period that researcher James C. Scott calls “high modernism”.

What is it?

It’s a kind of social engineering. According to Scott, the authorities used high-modernist projects to build a society rooted in rationalism, making people live under the banners of liberty and democracy.

Can you provide some examples of such high-modernist projects?

In the 20th century, the Europeans took an interest in city planning and started creating city makeover plans. The documents show that the designers created not just city spaces but social patterns, meaning they wanted people to live in the city in a certain way. Most of those projects targeted the middle class. The post-war reconstruction of Rotterdam is an excellent example of one such project.

Let’s talk more about it. The reconstruction of Rotterdam started immediately after the war, but the Dutch still hold exhibitions and celebrations to commemorate it. What makes it so special?

For the Dutch, Rotterdam is an iconic specimen of post-war reconstruction. The reconstruction of the city’s port heralded the start of the country’s restoration.

The Industrial Revolution affected some European countries in a bad way. Warsaw, for example, had ugly, chaotic development with tangled streets devoid of greenery. What was Rotterdam like before the war?

There were no urban development regulations in 19th-century Europe. Rotterdam, Warsaw, Birmingham, and Marseilles were all alike, with medieval-era quarters in the centre and residential areas for workers in the outskirts.

Central Rotterdam before the war. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Would a modern city dweller feel comfortable in the pre-war Rotterdam?

They would be surprised by space, odours, and sounds. The streets of Rotterdam were narrow and tangled, without any trees or separated carriageways. The air reeked of sewage and smoke from factory furnaces (judging by the archives, locals weren’t very fond of them). Meanwhile, there was less noise than in today’s cities because there were no cars in Rotterdam at the time. The factory bruit was heard only in the industrial quarters.

Why did the Germans bomb Rotterdam more than other Dutch cities?

To punish the Netherlands for resisting and shock the people. Bear in mind that Germany attacked the Netherlands despite the country’s neutrality. The Dutch started fighting back, so the Germans resorted to the “hit them where it hurts” tactic. They destroyed the country’s primary port and industrial city. Their plan worked: the Netherlands surrendered the very next day after the bombing. They struck at Coventry for the same reason — the city was a major British industrial, cultural, and historical city.

The Germans razed the country’s primary port and industrial city, and it surrendered the very following day.

Why did the Germans destroy only the central part of Rotterdam?

I believe the reason was twofold. First, they wanted to destroy the city without damaging the port, which they needed. Second, they wanted to strike at the Dutch urban identity because central Rotterdam was a typically Dutch place.

The central part of the city immediately after the bombing. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An aerial photograph of the city after the removal of rubble. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Which buildings and city elements were lost for good?

The 17th–19th-century development was utterly destroyed, including the city hall and the nobility’s houses. However, the slums, where the working class and beggars lived, suffered the most.

The Germans destroyed over 25,000 buildings, killing 850 people. How did city authorities manage to avoid substantial civilian losses?

I can hardly answer this question. From where I stand, however, it’s about interpreting the word “destroyed”. Most of the affected buildings were only partially destroyed. The Dutch themselves demolished them later.

As provocative as it may sound, the bombing was a blessing in disguise for local authorities. Before the war, they wanted to clear the centre from slums and poor people. The bombing finally enabled them to realize their modernist plans of making Rotterdam a world-class port city.

The bombing of Rotterdam was a blessing in disguise for local authorities.

The first Rotterdam reconstruction project was designed a mere two months after the bombing. I read that Dutch architects didn’t want the Germans to impose the Third Reich style on the city, hence the rush. Is that true?

It is, but their fears were not the only reason. The discussions about rebuilding the city began before the war, and architect Witteveen, who authored the first reconstruction plan, actively participated. I believe he already had an idea of how to do it.

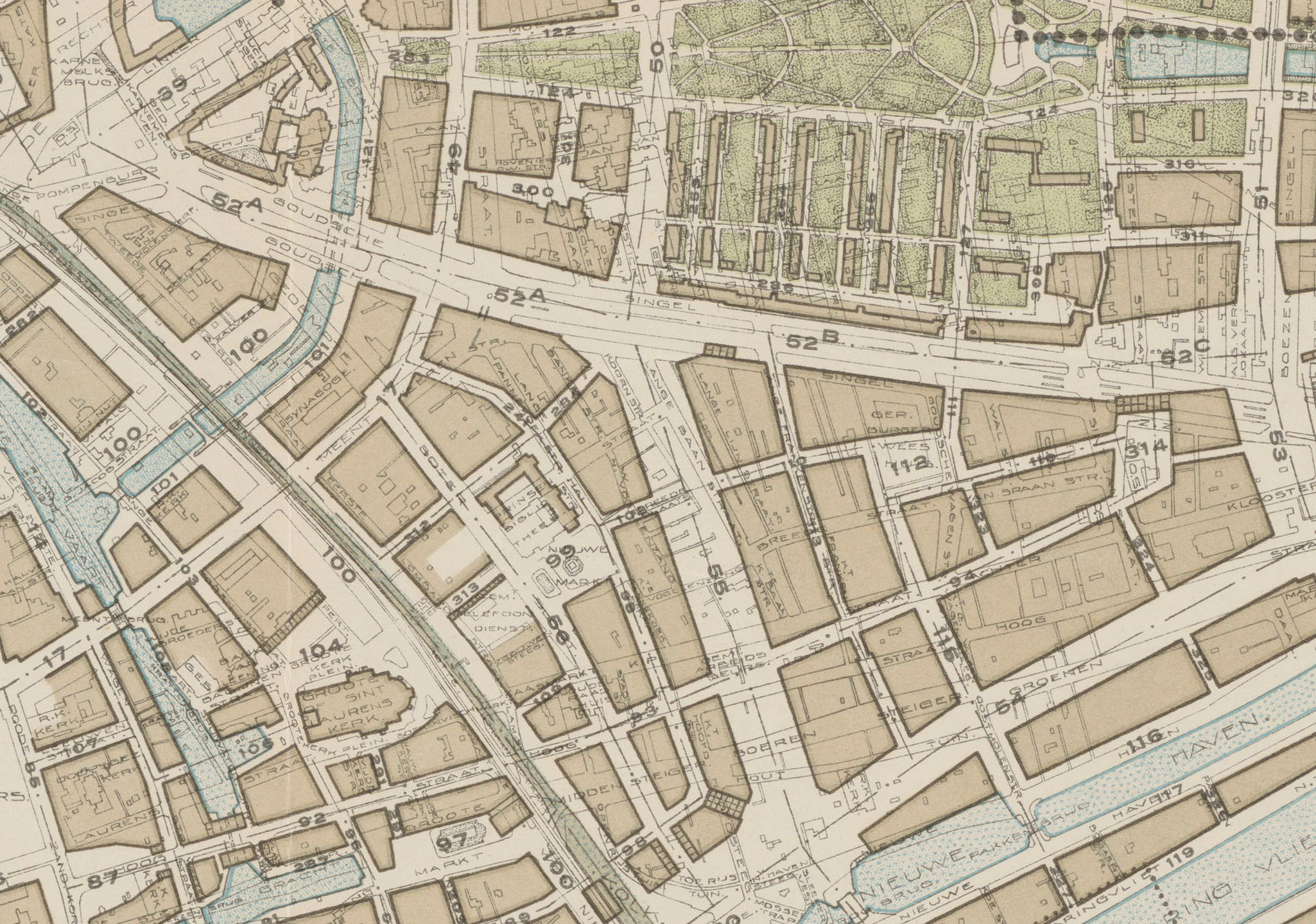

A fragment of Witteveen’s plan. The new quarters (in colour) are not aligned with the old city plan. Photo: Adviesbureau Stadsplan Rotterdam / Wikimedia Commons

In short, what was the plan?

They had a modernist vision for reconstructing the inner city, dividing the space into single-use zones, moving residential quarters from the central part of the city to the suburbs, and building shops, banks, and cultural and administrative buildings there instead.

How can you rebuild a city while under occupation and without an understanding of the occupiers’ plans and, more importantly, when and how the war will end?

As I already said, the plans to rebuild the city were made before the war. Besides, the Germans didn’t immediately appoint their people to the key positions in the Netherlands. Life was bustling here in the first years of the war. The industrialists, politicians, and architects discussed the future of Rotterdam with doubled enthusiasm. The institutions kept working from the first days of war and weren’t Nazified until mid-1942, but even then, the discussions of the city’s post-war development continued, even if underground. And then the Germans started losing the war.

I know that the first plan was turned down. Why?

Local elites wanted to break with the past. In their eyes, Witteveen wanted to preserve too many old buildings. He wasn’t modernist enough for them. Besides, the Germans approved of the first plan, and local authorities feared Nazis would take over the reconstruction.

The second plan, dubbed the Basic Plan, was created by Witteveen’s assistant Cornelis van Traa. In contrast to his former superior, this architect was more forward-looking. It took Cornelis van Traa two years to develop his plan.

The reconstruction of Rotterdam began in 1946. The ruins in the central part of the city had been removed by then, and vegetables and crops were planted in their place to feed people. Did this idea work?

It did. The winters of 1944–1945 were harsh, and those vegetables helped the locals survive.

A cornfield in central Rotterdam in 1943. Photo: Centraal Fotopersbureau / Wikimedia Commons

What makes the reconstruction-period architecture stand out?

Many standard buildings and even neighbourhoods appeared. Many of them mixed various age and social groups, multi-storey and private houses, housing for older people, etc.

The nationalization of land sped up the reconstruction of Warsaw and Coventry. The authorities there didn’t ask landowners for permission to demolish or reconstruct buildings. How was this problem tackled in the case of Rotterdam?

The land in Rotterdam was a municipal property even before the war, so there were only problems with real estate. The authorities set up a scheme to compensate owners for demolished buildings.

Why did they decide not to reconstruct the historical buildings and streets?

Again, the decision was ideologically-driven. The investors believed in modernism. They wanted the future, not the past.

In Ukraine, attempts at contemporary architecture in historical neighbourhoods always lead to scandals, with the people saying you cannot just break with history. How did the Rotterdam residents react?

Nobody asked them. The authorities, modernist architects, industrialists, and port entrepreneurs made the decision themselves. The reconstruction was accompanied by a sprawling campaign. Tours, exhibitions, leaflets — it all had to convince locals that everything was done in their interests. I studied the propaganda of that time. It spoke of making joint efforts and the fortitude of Rotterdam residents. However, nobody asked what was their lives like and what they wanted.

They didn’t even protest, did they?

The conservatives organized a protest movement, but it didn’t develop into activism. They managed to preserve the Grote of Sint-Laurenskerk church and a few other buildings in the central part of the city, but that was all. In the 1950s, residents started feeling nostalgic about medieval streets, landmark buildings, and even slums. But nobody walked out to protest.

The thing is that the middle class was fond of the new neighbourhoods and housing. They had spacious, warm dwellings with toilets and gardens. The shops were nearby. Everything was in order.

The reconstruction of the Grote of Sint-Laurenskerk in 1952. Photo: Daan Noske / Anefo / Wikimedia Commons

So, we have discussed making convenient and practical streets and planting vegetables in the empty central part of the city. I don’t see any social engineering in the reconstruction of Rotterdam so far. Where is the “high modernism” that you spoke of in the beginning?

It’s about what the local authorities did to slum dwellers. The thing is that besides workers, the slums were full of the unemployed, prostitutes, and the homeless. When the slums were bombed, all those people were moved to the city outskirts to live in shacks made of wood or rubble. It may seem like an act of benevolence at first sight. But it wasn’t so.

The Dutch government attempted to solve the problem of fringe groups even before the war by setting up correctional camps for them in Utrecht and Amsterdam. After the capitulation, the settlements for displaced persons near Rotterdam had a similar use. City residents were often put there against their will to be overseen by social workers. Also, men from those camps worked for the Germans.

Reminiscent of a concentration camp, isn’t it?

A writer, who published a novel about these settlements, said that the only difference between them and concentration camps was the lack of barbed wire. I studied this aspect myself, too. It turned out that the government mulled over sterilizing the residents there. But it was toward the end of the war.

Talking about the restoration of Rotterdam after the war, people often focus on the achievements, preferring to keep the correctional camps to themselves. There were achievements indeed: the development of the middle class got a boost. However, less well-to-do city residents were confined to those camp settlements and excluded from city life. We are talking about 8,000 Rotterdam residents. It is yet unknown how many people left the city, fleeing the camp life.

What happened to those settlements after the war?

The settlement in the Noorderkanaalweg neighbourhood, where the most problematic people were put, just disintegrated. By the end of the war, its residents took it to pieces, selling furniture to feed themselves and turning shacks into firewood.

In other ones, people lived until the end of the 20th century — one of them was demolished only in 2006. The tragedy is that those camps were intended to last only 5–10 years.

A temporary settlement that was still inhabited as of 2005. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Do you mean that temporary housing for displaced persons is a bad idea?

It is a necessity sometimes, but the authorities need to ensure it doesn’t become permanent. Otherwise, this kind of stigmatization is unavoidable. By the way, some Rotterdam residents still perceive the former residents of the settlements, which were set up in the city’s outskirts after its reconstruction, as socially inferior.

In the 1960s, the city authorities revised the reconstruction plan again. What didn’t they like about it again?

The plan remained, but the city life changed. In the 1960s–1970s, the architects moved from the concept of a technocratic city to that of the sociocratic one, starting to cater to the city residents’ needs and desires. The planning became more flexible. Urbanists said, okay, so here is how people live; now, how can we make their lives more comfortable?

Which elements of the plan didn’t withstand the test of time?

It’s hard to tell. The modernist ideas of the 1940s–1970s solved some problems but gave rise to other ones. Single-use zones, residential neighbourhoods in the outskirts — those didn’t work out. The residential areas in the south of Rotterdam are now the poorest in the country. I wouldn’t say those were wrong decisions to make; it’s just that living standards have changed.

Ossip Zadkine’s sculpture The Destroyed City in present-day Rotterdam. Photo: Depositphotos

Was Rotterdam’s reconstruction experience used in any other city?

Hardly, because all cities were rebuilding at once. The standard quarters first erected in Rotterdam were later built all over the country, though.

I know that giving advice is ungrateful. Still, what would your advice be for the architects involved in the post-war reconstruction of Ukrainian cities?

I should stay humble and reserved here, but if I have to say something. First, the architects and authorities need to ensure that the temporary housing doesn’t become permanent. As I said, it will lead to stigmatization of the people living there. Second, they should create inclusive projects and involve the residents in the design process.

New and best