“The Idea to Start Rebuilding During the War Was a Success”: An Architect on How World War 2 Improved Warsaw

The rebuilding of Warsaw in the 1940s is a prime example of post-war city reconstruction. After six years of bombing and the destruction at the hands of retreating Germans, the Poles managed to not only rebuild their capital but also rectify its pre-war architectural flaws. As a result, the reconstructed old city of Warsaw was included on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

This architectural feat was achieved by Biuro Odbudowy Stolicy or BOS (The Bureau for the Capital’s Reconstruction), an institution employing 1,500 people: architects, lawyers, journalists, and many other professionals. They set aside their ideological and political difference to make Warsaw “the best city in the world” over the next five years.

Grzegorz Piątek, an architect and the author of the book Best City in the World. Warsaw During the Reconstruction of 1944–1949, studies the work of BOS and the post-war reconstruction of the Polish capital. He told Bird in Flight how it took a mere year for the institution’s employees to create a plan to rebuild the city with a million-strong population, why Warsaw residents didn’t like them, and how the Poles’ post-war experience could be helpful to Ukrainian architects.

What was Warsaw like before World War 2?

Warsaw was a disaster in the eyes of modernist urban planners: with a population of almost 1.5 million, it had a population density of 15,000–20,000 people per square kilometre in the central part of the city and 10,000 people per square kilometre on average, three times higher than now. It had lots of low-quality housing and was chaotically developed. Nobody thought of it in terms of prestige or comfort. There was no electricity, gas, running water, or plumbing. There were no public spaces, national museums, galleries, and buildings to accommodate state authorities. There was much less greenery, with trees sparsely planted in the city’s parks. The streets were hard to navigate, with almost no way to cross the city from West to East or from North to South smoothly.

Why was it that bad?

The Industrial Revolution brought many people from the countryside to Warsaw. All those people had to live somewhere. The city was booming, but primarily low-quality housing was built.

A hundred years under Russian rule also took their toll. Historical buildings were not renovated but rebuilt to accommodate businesses. As a result, Warsaw became rather a large than a great city, and people didn’t perceive it as a capital for a long time.

How would you describe Warsaw after World War 2?

A sea of ruins.

Razed Warsaw ghetto. Photo: AKG

What was the scale of the destruction?

It’s still disputable, but it’s safe to say that at least 60% of buildings were destroyed beyond any sense of reconstruction. Others were partially destroyed or intact.

Were there any areas left intact?

The best part of the city on the Vistula River’s right bank was annihilated. Its right-bank part was less damaged because the Soviet army entered it earlier.

I need to point out that many cities were destroyed, like Rotterdam, Berlin, Dresden, Minsk, and Stalingrad. However, people think that Warsaw’s case is special. And there’s some truth to this. After the Warsaw uprising of 1944, Germans knew that the Red Army would enter the city within weeks, so they started destroying buildings one by one. They did it consciously.

The Germans consciously blew up buildings one by one in Warsaw.

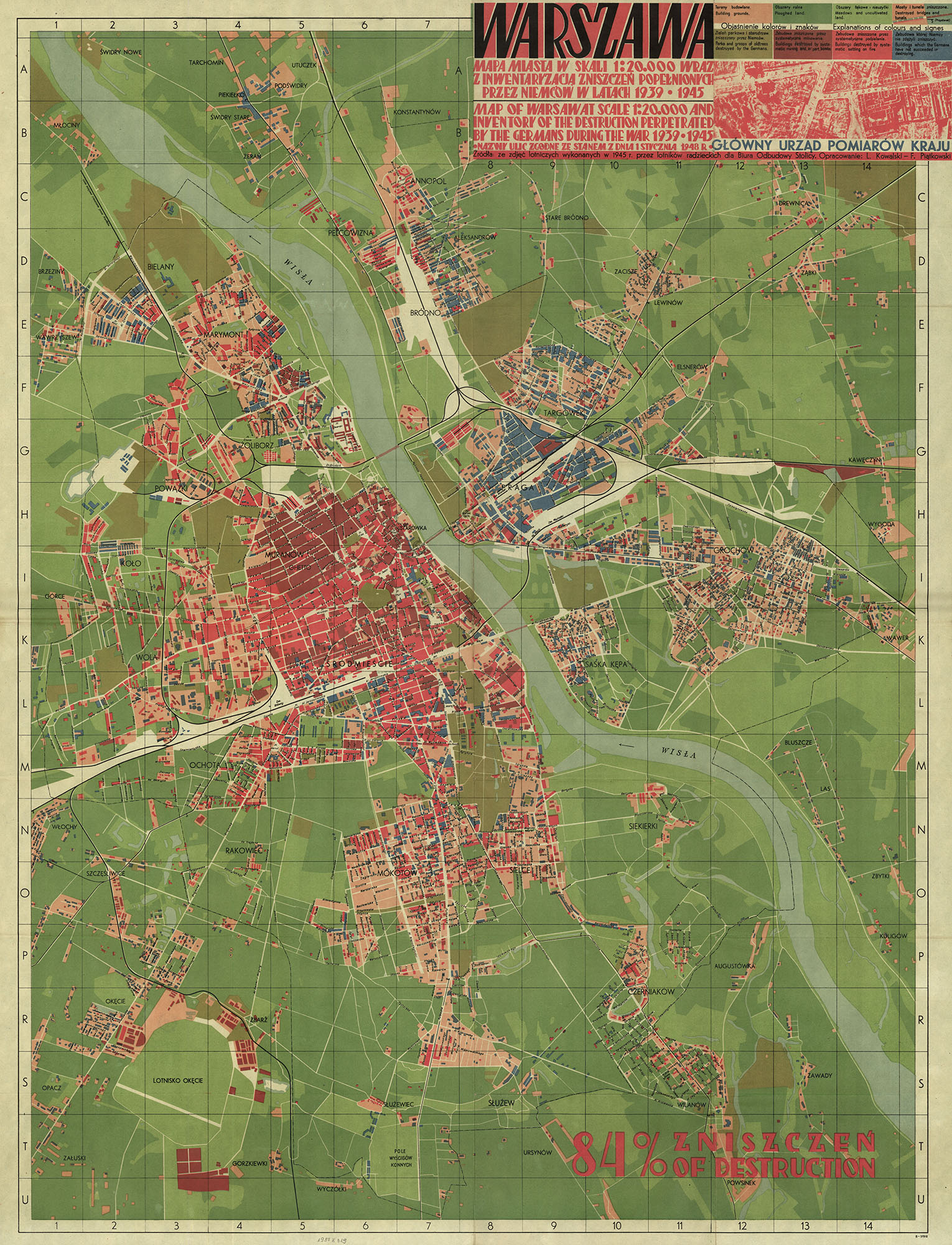

The map of destruction in Warsaw based on the aerial images produced by Soviet pilots in 1945. The intact buildings are marked in blue, and brown shows the damage (the completely destroyed installations are marked in dark brown). 84% of buildings were damaged. Photo: polona.pl

The authorities planned to leave Warsaw in ruins as a war monument at first. Still, it was eventually rebuilt. According to some researchers, it was done by order of Stalin. Others say locals just started rebuilding the city on their own. Which one was it in reality?

It’s a rare occasion when things start from the bottom up and from the top down and meet in the middle.

From a purely economic point of view, it didn’t make much sense to rebuild Warsaw. There were no building materials, not to mention money. Some believed it would be better to make the de facto seat of government in Lodz, which suffered less destruction, keeping Warsaw nominally as a capital. And it would have happened if not for the people returning to the city. The authorities tried to stop them for a few days by setting checkpoints at the entrances to the city, but it was impossible. People just started to remove the rubble and rebuild their houses.

People started returning to Warsaw immediately after its liberation, beginning to remove the rubble. The authorities couldn’t stop them.

Meanwhile, Stalin ordered to launch the reconstruction of Warsaw as soon as possible. He believed that people would not treat the government in Lublin or Lodz seriously.

Biuro Odbudowy Stolicy (BOS) was established to restore Warsaw, and the organization was unique in many ways. Tell us about it, please.

It was a “super-institution” that had all kinds of responsibilities, from removing rubble to urban planning and charting the city’s development over the following 50 years.

BOS included 1,500 people. Who were they?

In addition to architects and engineers, there were artists and photographers who documented the destruction and the reconstruction. Also, there were lawyers, economists, and journalists, who promoted the project via their own newspaper.

Curiously, BOS included architects with different political backgrounds: communists, nationalists, and even those who returned from England after the war. The latter would have been treated very suspiciously if they had worked in other fields. However, architects were essential to this, so they were accepted.

Clearly, there were a lot of different opinions among those people. How did they find common ground?

In general, it’s easy for architects to forget who they work for and what purpose they serve politically. Politics were not a topic, and everyone was focused on work.

The title of my book is translated as “the best city in the world”—I took it from one of the publications that accompanied the first post-war plan for Warsaw. It said in big letters that we build the best city in the world–Warsaw. It sounds almost absurd, but that was the feeling for the first couple of years after the war. The architects got an opportunity to build not only a better city than before the war but also maybe the best city in the world.

I know that BOS used Canaletto’s 18th-century paintings as a reference for reconstruction. Why not the 20th-century photographs?

Canaletto worked in the end-18th century during the reign of the last Polish king. Warsaw was the capital of the country at that time. Logically, the city’s appearance at the time was seen as original.

What was BOS’s idea of the plan and scenario for the reconstruction of Warsaw?

They wanted to rebuild Warsaw as a modern, practical city as envisioned at the time: with high-quality housing, a straightforward public transit system, single-use zoning, and much more greenery. That is to say that BOS wanted to put into life the modernist idea of the quality of life. Besides, they wanted to make a proper capital out of the city.

Was there a general plan for Warsaw?

Yes, the 1946 plan. Although fairly general, it became a basis for the following versions throughout the entire period that the communist government ruled in Poland. It took less than a year to develop. BOS members had started thinking about the future during the occupation—it helped a lot because, after the war, everyone knew what they wanted. In 1945, they just met in Warsaw and exchanged their ideas. As a result, the decisions were made quickly.

How could they analyze data so fast?

BOS members started inspecting buildings immediately after the liberation of Warsaw. In a few weeks, they visited 10,000 buildings. Granted, their analysis was relatively shallow with tiny notes such as “Five storeys, wooden structure, burned down”. It was their way of assessing which buildings could be saved.

What were the principal problems that the architects faced while rebuilding Warsaw?

The first was the conflict between long-term planning and short-term needs. Architects had a vision, but they couldn’t ignore the fact that people needed housing ASAP, and institutions required premises. They had to compromise, preserving some buildings they didn’t like that were fit for use.

Second, they had no resources. BOS wanted to use modern materials but had to make do with whatever was left after the war. The intact bricks were reused, and construction waste was ground to make concrete, so called gruzobeton. The Muranów neighbourhood was built in place of the destroyed ghetto from gruzobeton. Also things like baths, door handles, handrails and many others were salvaged from the ruins to be installed in the reconstructed buildings.

A building in the Muranów neighbourhood constructed from concrete with added construction waste. Photo: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

Third, locals were sometimes sceptical about what BOS was doing. Over the first two years, people saw no breakthrough results. They thought that the egg-head architects were sitting in their ivory tower while 600,000 Warsaw residents had to live without street lighting and public transit—some even without a roof over their heads. BOS kept working only because public opinion could be ignored. Locals had no tools for influence—there were no public consultations at the time. We do know that locals were outraged from the press, which was relatively free in the first couple of post-war years, from the satire, personal letters, and journals.

This one needs an explanation. In my view, there were two kinds of criticism of the reconstruction: politically motivated and the one due to people losing their property because of the reconstruction.

The thing is that the Polish government nationalized all the land within the city limits. Otherwise, the rebuilding would be impossible because of the sheer number of landowners one had to negotiate with. By the way, this was one of the reasons behind the failure to improve the city before the war. With the nationalization, the authorities hit two birds with one stone, enabling the architects to work and taking the property from “the bourgeoisie”. The walkouts of former property owners also became a target of propaganda attacks. They were ridiculed with caricatures, in which the pre-war bourgeois capitalists were drawn criticising the reconstruction while sitting in old-fashioned interiors.

Regardless, it was an extraordinary moment in history to rebuild the city because hardly anyone in the destroyed Warsaw cared about property. People returning to the city could settle in any intact building.

Which of the city’s pre-war problems did the architects eliminate through reconstruction?

All of them, I think. I mean, not in the first five years after the war, but in the long term.

Warsaw’s planning structure was streamlined, a proper street grid was created in the central part of the city, and it became easy to traverse the city as well as go around it via the circular road. Historic landmarks, including the Royal Castle (finished in the 1980s), were given a facelift. We can’t say that Warsaw has become the best city in the world, but it is certainly closer to that than it was before the war.

The quality of housing drastically increased after the war. The flats were small but practically planned, complete with bathrooms and windows. There was greenery near the houses, too.

Perhaps, BOS didn’t make as many public spaces as it should have. However, housing was a priority for decades after the war, unlike public spaces.

What were the reconstruction authors’ principal mistakes? Do we observe them now?

The first was the modernist idea of dividing the city into single-use zones. Its consequences are apparent to this day. The largest single-use office zone in Warsaw is known as Mordor. Locals hate it. It’s a former single-use industrial zone converted into a single-use office one. The function changed, but problems remained: this neighbourhood stays empty in the evenings and on weekends. On workdays, everyone goes to work there in the morning and hurries to get out in the evening because of the terrible traffic.

Another problem is that wide avenues and straightforward road and quarter system resulted in cars flooding the city. The new avenues turned into noisy transport arteries, and now they are rather dividing neighbourhoods than connecting them. Also, they are inconvenient to cross. The planners couldn’t have predicted this, though.

How much did it cost to rebuild Warsaw?

Nobody knows. There are some estimates of damages, but they don’t reflect the reconstruction costs, as the city wasn’t restored but rather built anew.

Besides, there is no precise date to mark the end of the reconstruction. The authorities said it ended in 1949, but the work on the old city centre wasn’t finished until 1953, and on the Royal Castle—until 1984.

Much work was done free of charge with the materials donated by other countries or produced from construction waste. How do you count the cost of all that?

Present-day Warsaw. Photo: Depositphotos

BOS was disbanded in the end-1940s while the reconstruction continued. Why?

The situation normalized, and the responsibilities of BOS were returned to traditional institutions.

Besides, the honeymoon period, during which the communists pretended to make Poland a happy social-democratic country, ended in 1949, giving way to hardcore Stalinization. The communist party monopolized the economy, art, social life, and architecture. The social realism imported to Poland by the communists became the only possible style of architecture. BOS had to go. Ideologically, its disbanding meant that the authorities stopped the reconstruction and started building a new city, new country, new identity, and new people. It didn’t need an institution with the word “rebuilding” in its name. Even the Ministry of Reconstruction was renamed the Ministry of Construction.

Also, there was a political aspect to that. When BOS delivered the first results in 1949, rebuilding the Royal Tract and a small portion of the old city, the government just closed it and appropriated the achievement.

Did BOS fulfil its objectives?

It couldn’t achieve them within the shortest time possible, so you can see BOS as a failure.

BOS was shut down in 1950. However, its work laid the foundation for city planning for next decades. Much of what we currently see in present-day Warsaw is a result of the decisions made by BOS.

Why did it fail?

After a short period of inspired enthusiasm, life took its toll. BOS had to reckon with not only politics but also the economy. People in Warsaw hoped that the entire world would help them rebuild after the war. They would get a dozen buses from London or 600 prefabricated houses from USSR, but it wasn’t the scale of help they expected.

People in Warsaw hoped that the entire world would help them rebuild after the war, but the actual scale of help was small.

The Ukrainian Mariupol now lies in ruins, with 90% of buildings damaged there, and thousands of buildings were destroyed in Kharkiv and Chernihiv. Which approaches to the reconstruction of Warsaw could be applied in Ukraine after this war, in your opinion?

I believe it is essential to establish the institutions and analytical centres now to provide data and know-how to hit the ground running in the very first days after the war. As cynical as it may sound, Polish architects and planners kept thinking, discussing, and drawing, even though they couldn’t know for sure when the war would end.

It’s great to have an opportunity to turn the post-war horrors into something beautiful. Restoring the city structure as it was with all its problems would have been much worse.

One of the ways of dealing with the tragedy would be to have a very open discussion on what architects and city residents liked or not before and then try to tackle the problems while rebuilding the city after the war.

It’s hard because you offer to launch a discussion on what we didn’t like in our favourite but now mutilated cities.

Yes, it is. It still escapes me how Polish architects managed to pull it off. Perhaps, they had some kind of realization as to what happened throughout the years of occupation. The war in Ukraine has continued for only several weeks, so it’s hard to think about reconstruction now. However, that moment will eventually come.

It may sound inappropriate, but a politician that has won the elections has three months to make the most important decisions while riding the wave of popularity. The same thing is true for the reconstruction. It’s essential to use the post-war enthusiasm to tackle the old architectural issues, among other things. The decision to rebuild Warsaw while the war was raging on in the West seemed irrational and ridiculous but turned out to be a success.

Photos in the cover collage: Wikimedia Commons, Depositphotos

New and best