Beyond Repair: The Anthology of Mariupol’s Mosaics

Mariupol used to have one of the most extensive collections of decorative art. Considering that monumental art lacks appropriate protection in Ukraine, the mosaics were under a constant threat of destruction.

Now, after four months of the Russian occupation, the future of Mariupol’s mosaic art remains uncertain.

Stanislav Ivanov — a Mariupol-based photographer and one of the authors of the All Shades of Mariupol’s Mosaics book — spent 20 days in the city under the Russian occupation and now resides in Lviv as a displaced person.

Owing to him and the book’s co-author Oleksandr Chernov, all 26 mosaic panels of the Azov Sea littoral that remained intact before the 24th of February are now preserved on the pages of the comprehensive guide to the Ukrainian monumental mosaic of the Soviet era.

A photographer and monumental art researcher, he co-authored the All Shades of Mariupol’s Mosaics book.

— I started photographing pieces of monumental art ten years ago, albeit without any intention of studying them. Then I met regional ethnographer and collector Oleksandr Chernov. The time I spent with him shaped my broader view of art.

The idea of making a book occurred to us two years ago when we stumbled upon the decrepit workshop of monumental artists Valentyn Konstantinov and his friend Lel Kuzminkov in Mariupol. They were the authors of many mosaics and reliefs in the city. Konstantinov passed away in 2012, and his wife even earlier. His children all departed. Nobody returned to the workshop for eight years. It looked awful. Upon seeing it, Chernov and I decided to create an anthology of monumental art in Mariupol before it suffered the workshop’s fate. Our reason for documenting mosaics of all things was that they draw society’s attention the most of all monumental art genres.

The idea of making a book occurred to us when we stumbled upon the decrepit workshop of monumental artists Konstantinov and his friend Kuzminkov in Mariupol.

Nobody knows how many monumental mosaics there are in Mariupol. The information about many of them was lost, and any that has been preserved is all speculation and hoaxes. It’s OK, though, because 50 years or even more have passed since they were created.

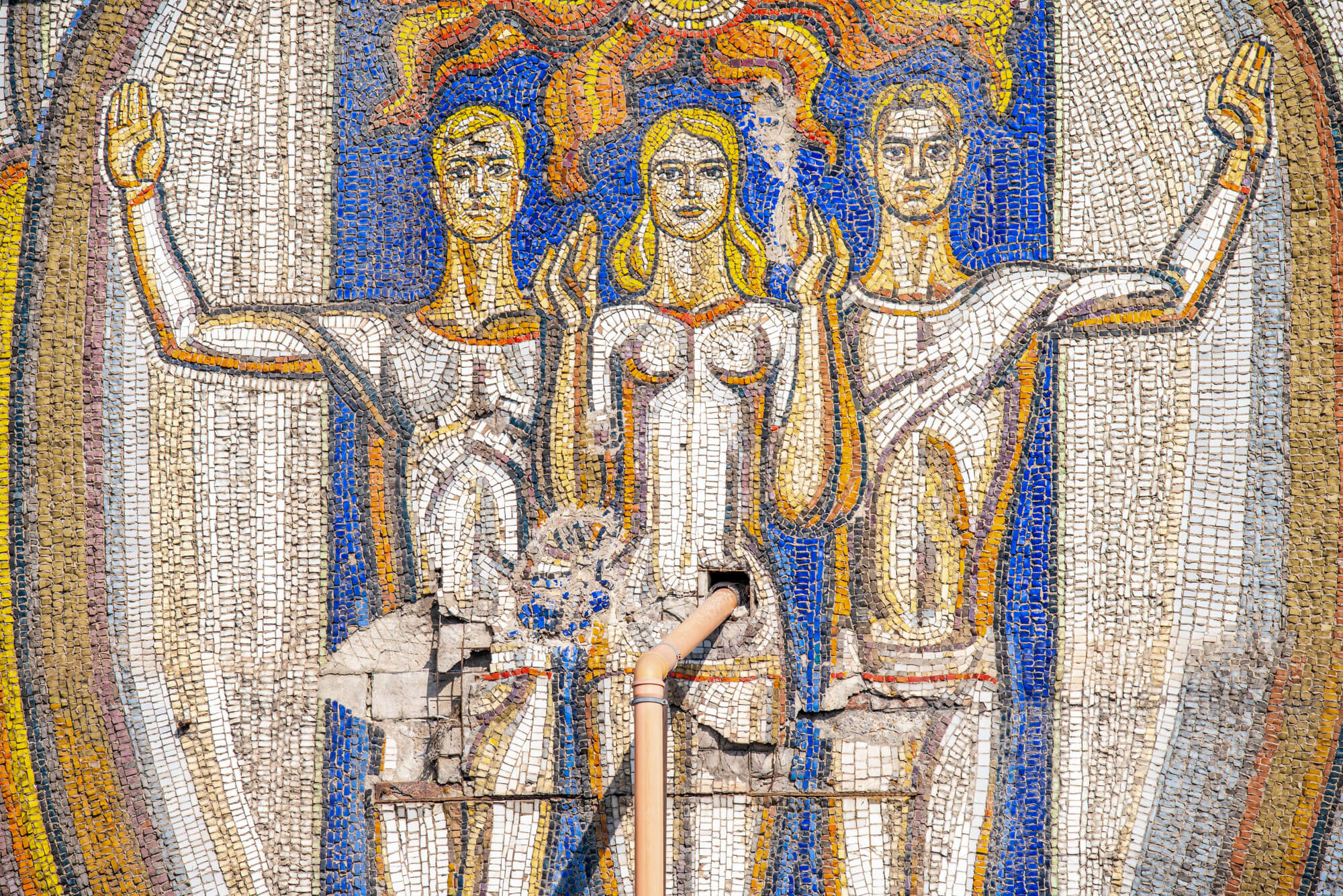

First-graders by Valentyn Konstantinov and Lel Kuzminkov

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko by Yakiv Rayzin, Mykola Tykhonov, Oleksandr Kechedzhy

Union by Yakiv Raizin and Mykola Tykhonov

Youth by Valentyn Konstantinov and Lel Kuzminkov (Soviet Army, Air Force, and Navy Volunteer Society)

It turned out that Oleksandr Chernov and I were the first to do in-depth research on mosaics of Mariupol. There were some publications and volunteer initiatives, but those were few and far between. No fundamental works existed. When we compiled the complete list of the works to be included in the anthology, we realized we knew nothing about a third of them. We started poking around and delved into archives to establish their creation dates and authorship. We worked in the regional ethnography museum and delved into industry periodicals.

Studying the mosaics of Mariupol, we made many discoveries. Take the city’s most famous one — Conquerors of Space. Its author Viktor Arnautov had nothing to do with its name — he didn’t name it in the first place. Conquerors of Space doesn’t even make any sense as its name.

The building on which the panel was used to house a post office and telegraph. The mosaic depicts a rocket and people with wires and comms equipment near it. Those are obviously communications operators, not spacemen. It would be logical to name that mosaic “Comms Men” or whatever. Still, somebody made a different decision based on the space theme that was wildly popular in the 1960s.

There is also the curious story of how one of the most prominent monumental ensembles in the Soviet Union was created. I am talking about the Azovmash ensemble that included Valentyn Konstantinov’s and Lel Kuzminkov’s Maternity, Sports, and Labour mosaics. From the authors’ notes we found in the archive, we learned that the ensemble was to include five mosaics and four auxiliary friezes with a total area of 500 m². Three people worked on the project besides Konstantinov and Kuzminkov. We managed to unearth photos and sketches of all those pieces. Who their authors were and where the other mosaics went is unknown. Most probably, they were destroyed in the 1970s.

Wind Fighter by Alla Horska and Viktor Zaretskyi

Space by Valerii Lamakh, Ernest Kotkov, and Ivan Lytovchenko

Metallurgists (Mariupol railway station)

Tree of Life by Alla Horska and Viktor Zaretskyi

Labourers by Yakiv Rayzin

In the context of decommunization, Soviet mosaics are often perceived as a product of propaganda. This stance is due to the Soviet view on art, which emphasized its ideological aspect.

I analyzed all 26 mosaics in Mariupol, and only three of them bore the formal ideological marks — Soviet insignia or the likes of it. The rest were social realism pieces without any ideological markers.

Of the 26 mosaics in Mariupol, only three bear formal marks of the Soviet ideology.

Those opposing the preservation of mosaics call them “Soviet art”, forgetting that monumental art has primarily global importance. Also, “Soviet art” is not the definition you want to use at all. The Soviet Union was a synthetic state formation without a nation of its own, so to speak, or any other defining features apart from the ideological ones. Therefore, the mosaics in Mariupol are more of a “Soviet-era Ukrainian art”.

For me, mosaics are works of art — nothing more, nothing less. Instead of making every effort to destroy these manifestations of the “inconvenient” past, we should adapt them to the contemporary context — this is the central message of our book, All Shades of Mariupol’s Mosaics.

We described 25 monumental author works, finding trustworthy information about all of them except one — Viktor Ponomariov’s Tourism and Recreation on the façade of the Tourist facility. We know neither the date of its creation nor who the co-author was. Ponomariov passed away many years ago, leaving behind no archives. Nor had he any students or followers who could tell something about Tourism and Recreation. I believe some information could be found in the archives of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine. However, it was lost on the edge of the 1990s and the 2000s.

Family by Valentyn Konstantinov and Lel Kuzminkov

Conquerors of Space

Conquerors of Space

Girl by Valentyn Konstantinov and Lel Kuzminkov

Mosaics by Petro Kot and Oleh Kovalyov

Youth by Valentyn Konstantinov and Lel Kuzminkov (Soviet Army, Air Force, and Navy Volunteer Society)

Sports (Azovmash)

Maternity (Azovmash)

We don’t know how many mosaics remain intact in Mariupol now. Considering that 90% of buildings in the city have been destroyed, chances are slim that the works survived. Most probably, Lel Kuzminkov’s and Valentyn Konstantinov’s Metallurgists mosaic in the railway station, two Maternity reliefs in the Communications House, Yakiv Rayzin’s Labourers, and Ernest Kotkov’s and Ivan Lytovchenko’s Earth and Space in the Iskra Palace of Culture all have been lost. In some places, façade mosaics were ruined, but the interior ones survived. However, those will be destroyed, too, if the buildings are declared beyond repair.

Buyers covered our expenses on the first run of the book themselves. We opened pre-orders for 20 copies, and it didn’t go to print until those were closed. We’ll stick to this model for the book to remain in print for as long as people want to buy it. To date, we’ve sold about 300 copies. While previously only monumental art aficionados purchased the book, it’s those who want to preserve the memory of the destroyed city who buy it now.

Photo: Stanislav Ivanov

New and best