Uneternal Values: How Cultural Heritage is Preserved in Lviv

Ukrainian museums and galleries outside of the area of hostilities are trying to preserve their exhibits while there is still time. They share little about their work with the public for security reasons. However, some items of cultural value cannot be hidden in bomb shelters, e.g., the survival of numerous churches and other landmarks in the public spaces is a matter of luck and competent specialists’ concern. Inna Dmytruk-Sorokhtei told Bird in Flight how volunteers preserve the monuments of Lviv, and Viktoria Pidust documented how their efforts transformed the city’s look.

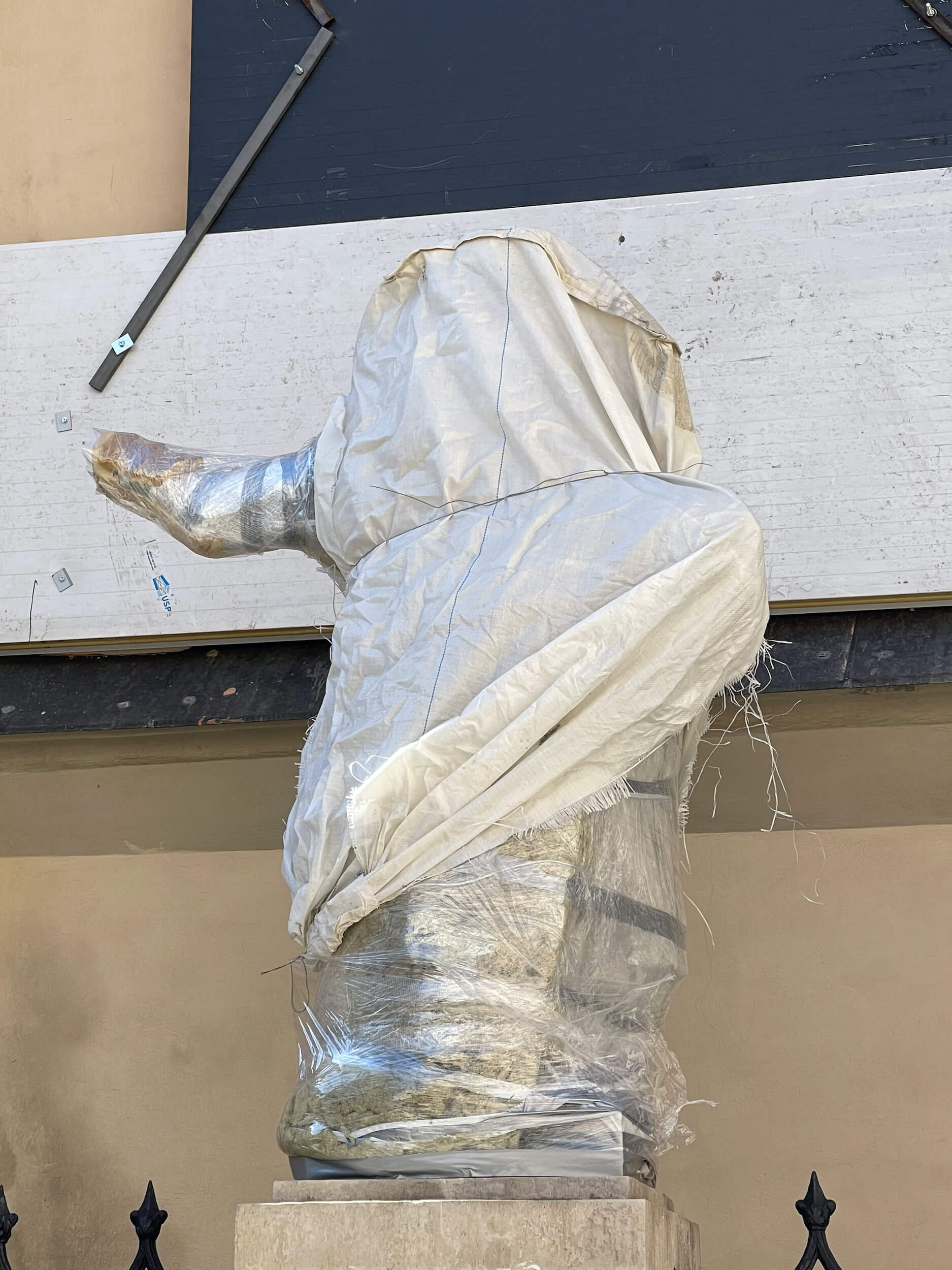

— Lviv is full of statues, stained glass, and other things restored a mere five years or even just a year ago. We have involved Polish artisans lately because there is a whole lot of international heritage from various centuries in the city. Sure enough, there is no difference now: whether it is a Polish, Ukrainian, or Armenian church, it needs to be preserved. It may not be immediately visible, but Lviv has always been about that, and with each new restoration, we rejoiced at preserving yet another landmark. There were some tremendous projects, too, like the restoration of the Saints Peter and Paul Garrison Church. A new restoration season had to kick off once the weather got warmer. We had many plans, but it happened otherwise.

I wish we could protect Lviv with a dome of some kind because its central part is nothing short of an open-air museum. And then, there is also a proper open-air heritage museum and numerous landmarks scattered across the city—most of them are concentrated in western Ukraine, especially the Lviv and Ternopil regions.

I wish we could protect Lviv with a dome of some kind because its central part is nothing short of an open-air museum.

There are organizations in Lviv that specialize in conserving landmarks of local and regional importance, including a charitable one headed by Andrii Saliuk. Typically, private organizations of this kind are more efficient in that they don’t have to deal with bureaucracy. On the second day of shelling in Ukraine, local art conservators gathered at the premises of this very organization. There were private specialists and those on the state payroll, too. They all came as volunteers to decide what to do next. The shock of the first day was huge, but we had to set the wheels in motion.

public figure, president of the charity fund “Preservation of the historical and architectural heritage of the city of Lviv”

Now we are working 24/7 because we all need to make money and pay taxes, and in the after hours, we are coming back to protect our landmarks. The adrenaline still keeps us going, even though it has been the third week of working already. Granted, we could use men’s assistance now and then. There is much physical work to do, but they are all currently with the Armed Forces of Ukraine or Territorial Defence Force. Still, people lend us a hand if they can, even teenagers.

We are doing literally everything. We go to home improvement shops, buy the necessary materials, and then wrap and cover the landmarks in the city. Our team includes not only art restoration specialists. Musicians help, too, and we even have one physicist. Although we have established a general protocol for what we do, it is not universally applicable, and we have to vary our approach on a case-by-case basis. For instance, access to some religious buildings is complicated, and we have to use cranes to cover sculptures and stained glass high above. Also, we finally can adequately collaborate with the officials, who help us get these very cranes.

However, our Polish colleagues provide the most support. First of all, they started advising us at once. Mind you, it is advice from the people with multiple degrees who know what to do and are all too familiar with the “Russian boot” that we are talking about. They also send money and loads of humanitarian aid—not the essential supplies, a lot of which are coming from Poland as it is, but the materials specifically for us art conservators. Besides, Polish specialists come here themselves, even though they realize how dangerous it might be.

The Poles have had no experience with anything like this since World War 2, but we found someone with a more recent history of wartime preservation of landmarks—the Croatians. We have recently spoken with a Croatian Minister of Culture and many restoration specialists from various industries. Talking about the movable and immovable architecture assets, landmarks, stone and wooden sculptures—both indoor and outdoor—as well as paintings on wood panels, like icons, canvas, and paper, we realized that those were all different art restoration niches, and so we invited people specializing in them on that round table discussion. Their skills date back 30 years instead of 70, so we make sure to follow their advice.

There is also a committee established by the Ukrainian diaspora in the USA and Australia. It primarily raises money, though, as it is hard to ship restoration materials from that far away. I am still stoked by how fast things are moving. I know all too well how it is with state-run museums when the procurement of restoration materials can take weeks because of bureaucracy. And here, I just pick all I need in the shop, take the receipts to the charitable organization, and two hours later, we can get the materials already.

Nobody knows how much time we have left. We have a list of landmarks that require protection, and we just go from one to another, sometimes returning to those we have already secured to adjust something. It is as if the list keeps growing day by day, and it’s a good thing because locals help us, reporting the houses with stained glass and other valuable items.

Nobody knows how much time we have left. We have a list of landmarks that require protection, and we just go from one to another.

Recently, we have been covering stained glass on the church, and the women near the stand close by thanked us so sincerely that it almost made me cry. Many people are scared, too, and our work makes them worry. We sure got used to seeing our city at its most picturesque, and now there are piles of sandbags and frameworks everywhere. Naturally, it is a depressing sight. Sometimes people approach us and ask: “Do you know something? Will there be shelling?” Seeing the destruction in other cities, I very much hope that we will escape this fate.

Some people poke fun at us, like, the shelling is way in the East—what are you doing here in Lviv? To which I usually answer: “Have you made a deal with him that he will not bomb you? Or do you have a direct line with the God, and he promised to cover you personally?” Moreover, I very much wish that my work was for nothing and we will unpack everything and return to the way it was before.

Some people poke fun at us, like, the shelling is way in the East—what are you doing here in Lviv? To which I usually answer: “Have you made a deal with him that he will not bomb you?”

We keenly understand that our work is as if an ant would haul water to put out a massive fire. Probably, it is just us soothing our consciousness. At least the stained glass will not be broken by a shock wave from a distant blast, or flying debris will be stopped by sheet steel or boards instead of breaking the window. I mean, we realize our measures will protect only from superficial threats. However, it never occurred to me that we could just sit by and do nothing.

Photo: Viktoria Pidust

New and best