Don’t Let Go of What You Love: Kyiv’s Modern Architecture as Drawn by Ole Solonko

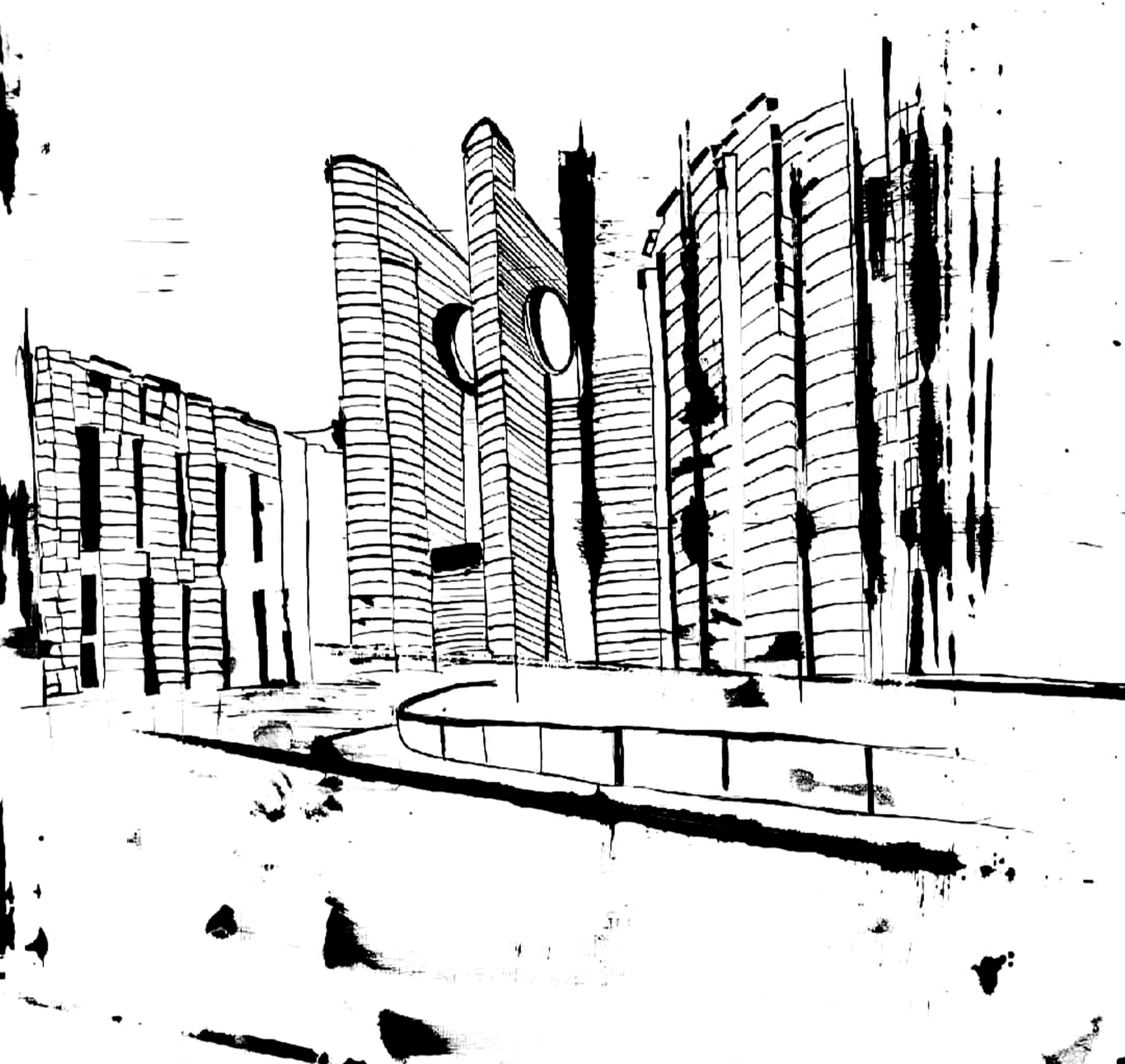

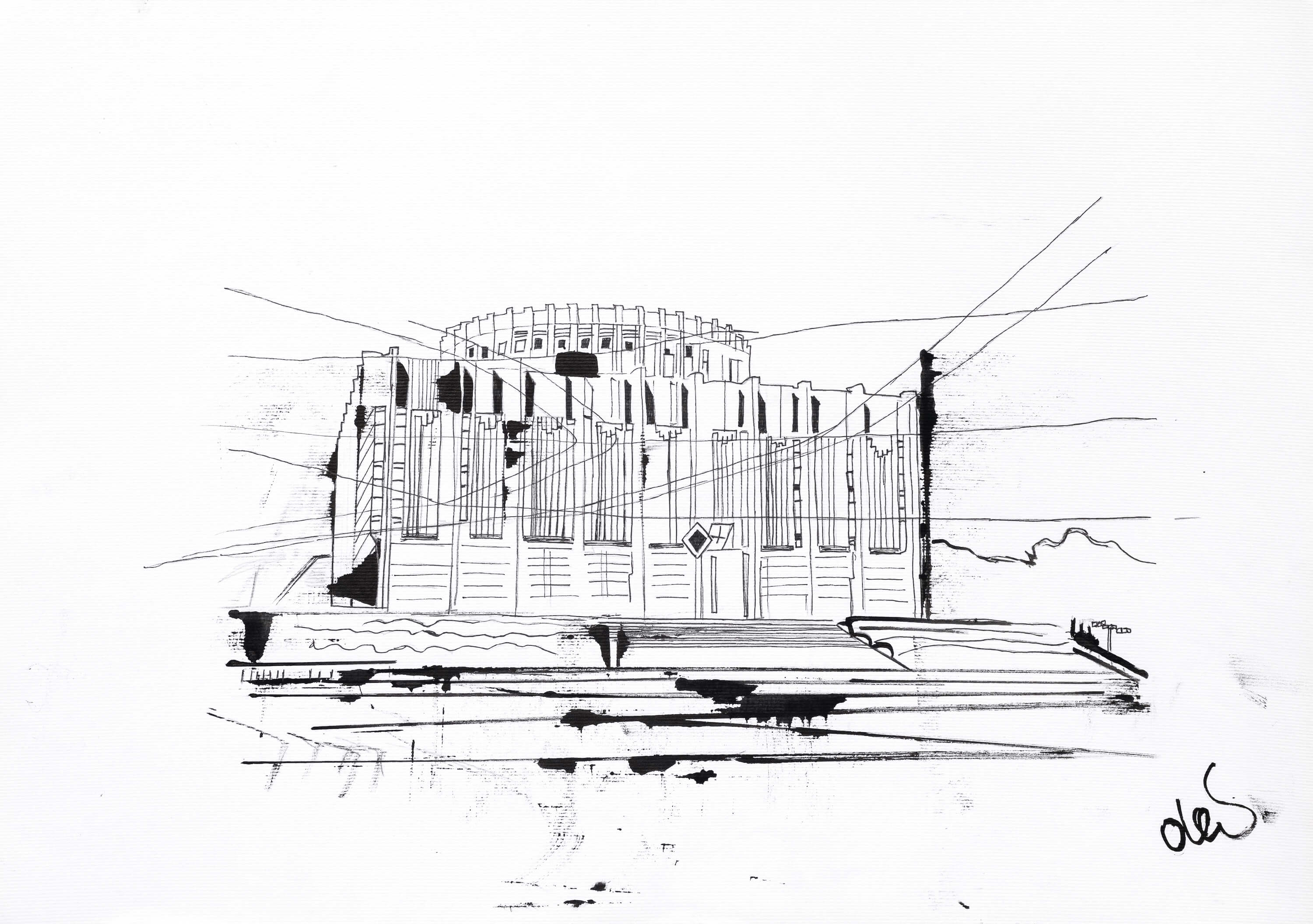

In the USSR, modern architecture began with the 1950s panel blocks of flats. Soviet architects had limited access to global practices and worked under much political pressure but still managed to create fantastic, futuristic buildings now known as the prime specimen of Kyiv Modernism or Kyiv Brutalism of the 1960s and 1970s.

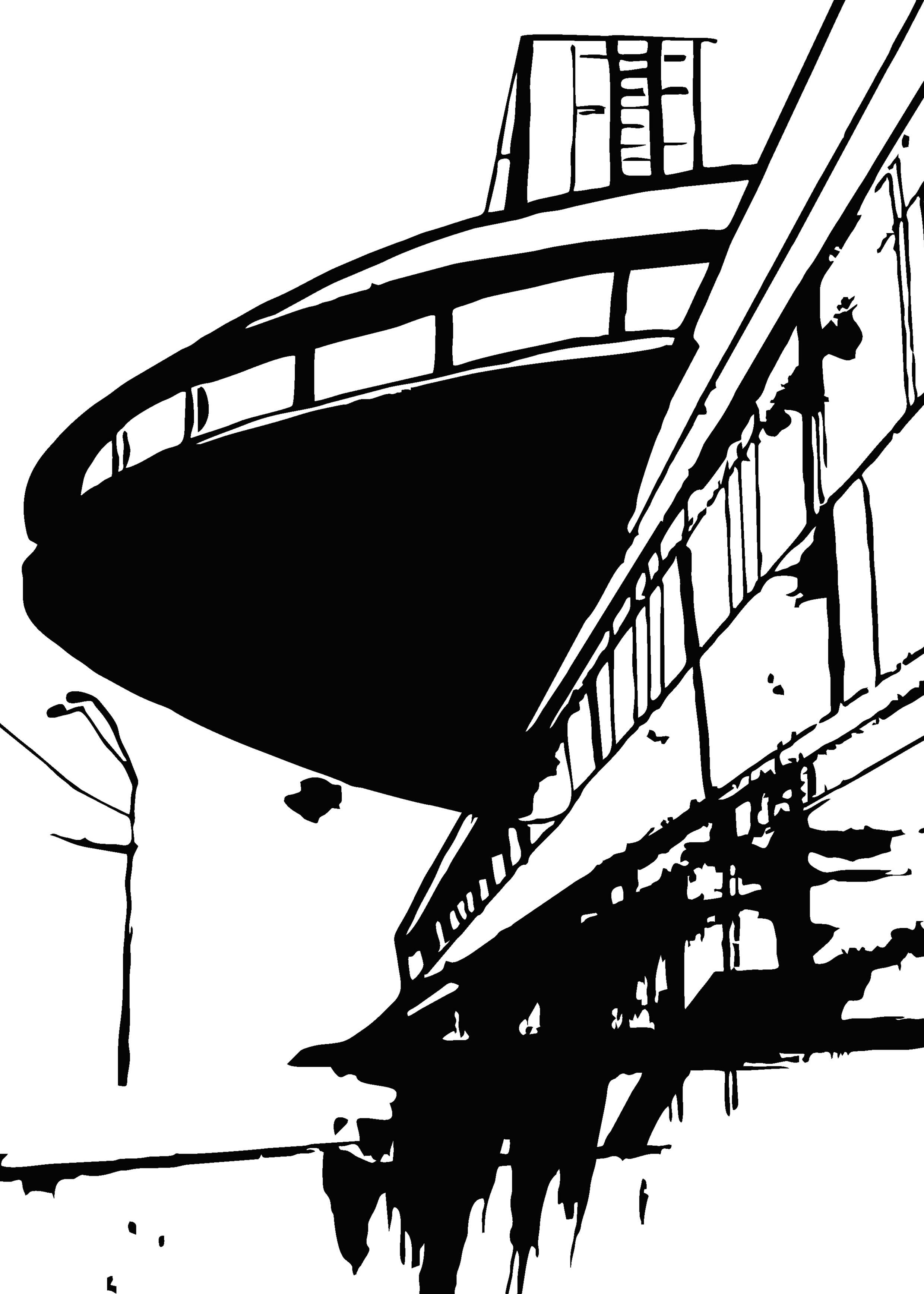

Among the architects who gave it prominence were Florian Yuriev (the author of the famous Tarilka building near the Lybidska metro station), Avraam Miletskyi, Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnychenko (the architects behind the Kyiv Crematorium building), and many others.

Nowadays, Kyiv Modernism has become popular and recognizable among locals and foreigners alike. French photographer Frédéric Chaubin released a photobook on Soviet modernism. Oleksii Bykov and Ievheniia Hubkina wrote theirs on Ukrainian modernism.

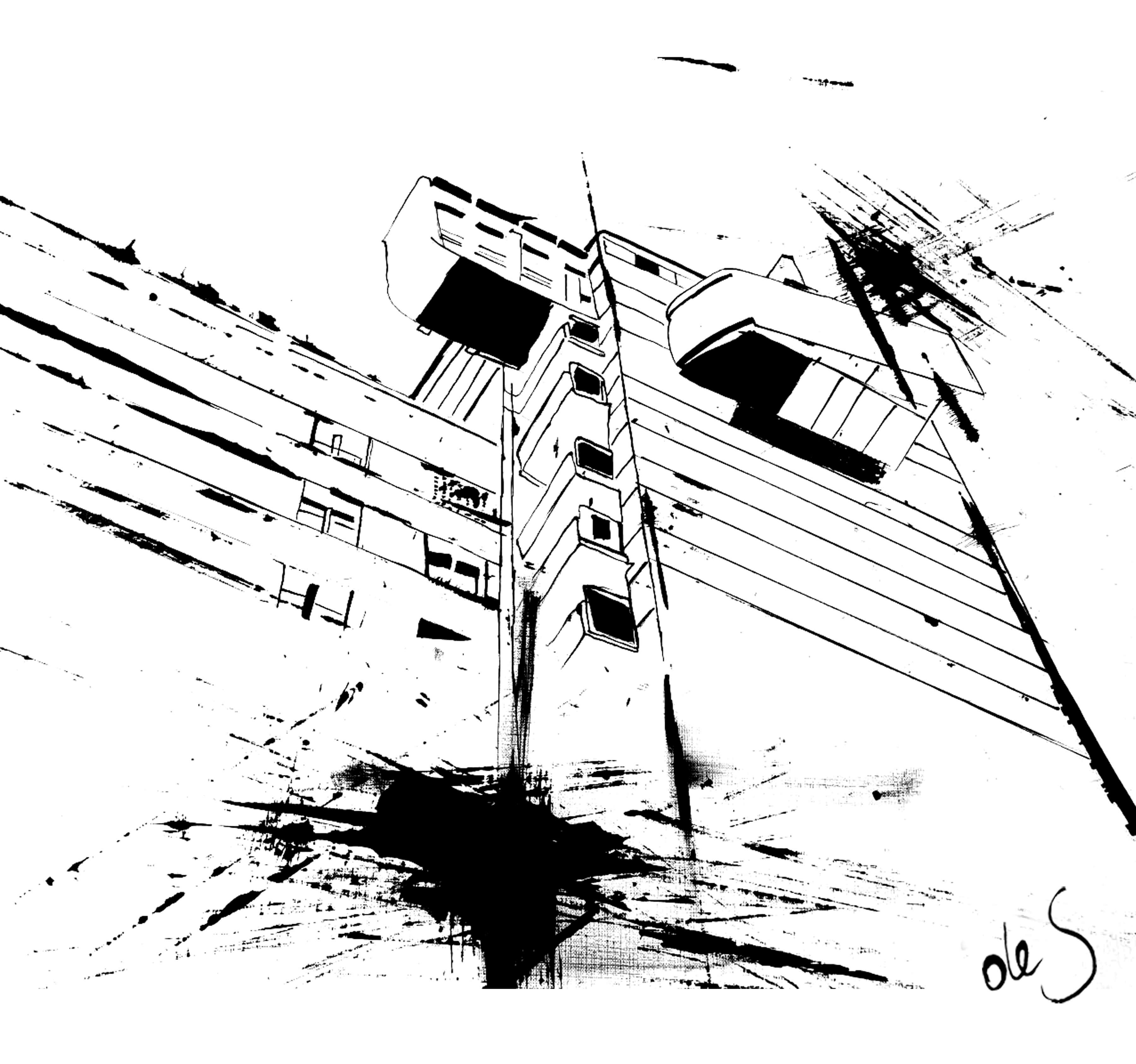

In 2020, Kyiv-based artist Ole Solonko started drawing landmarks of this architectural style. When the full-on invasion began, she continued the project, giving it a new meaning: as the war ruins buildings and entire cities, she is striving to preserve everything we could lose.

Artist and educator.

— The war caught me — and everyone else — by surprise. I was in Kyiv, and my mother and brother were in Bucha. Soon, I all but lost contact with them. My brother had to climb to the roof of their house to call me once a day. Those were the scariest and the longest days of my life. Eventually, they managed to leave Bucha — we are together in Kyiv now.

The first month of the war was hard. I worried about my family and my country overall. I had a hard time making myself do something, but I knew that occupying myself with work would help. At one point, my friend suggested starting a charity project — a drawing sale in Amsterdam. We dubbed it Reciprocity: Works From Besieged City. Through it, we raised some money — not a lot, but enough to donate to those who needed it, like the orphanage in Ovruch.

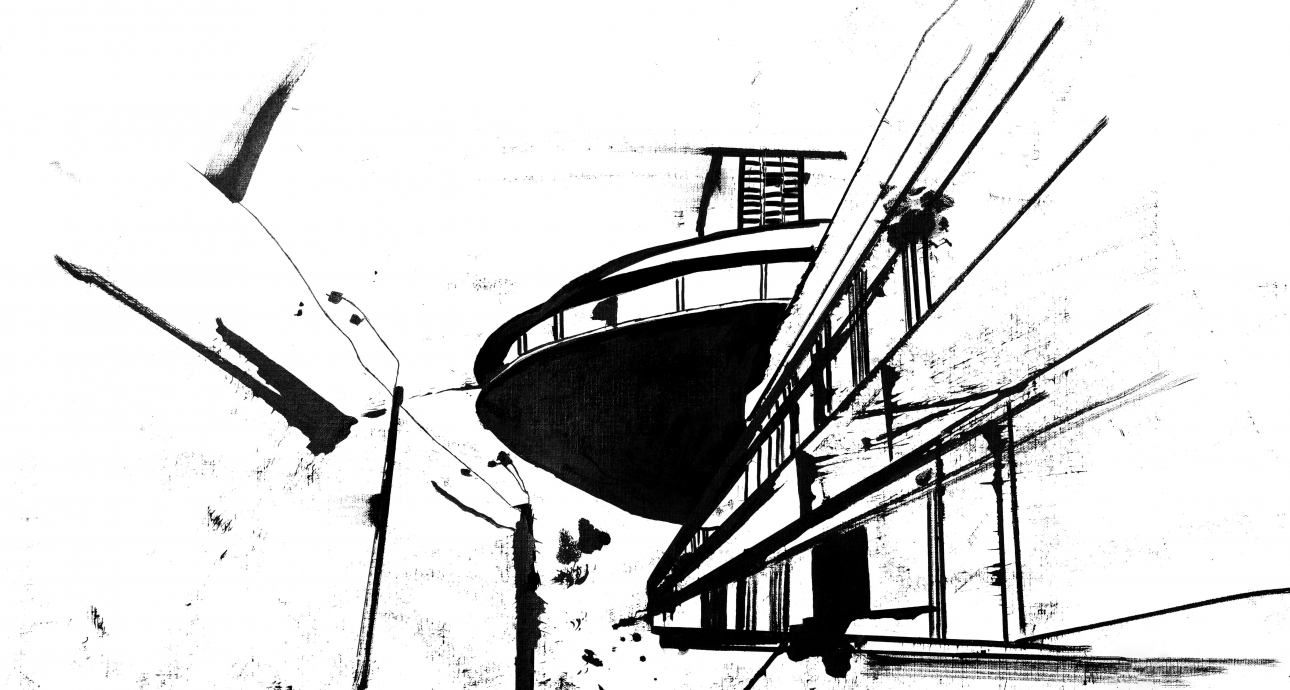

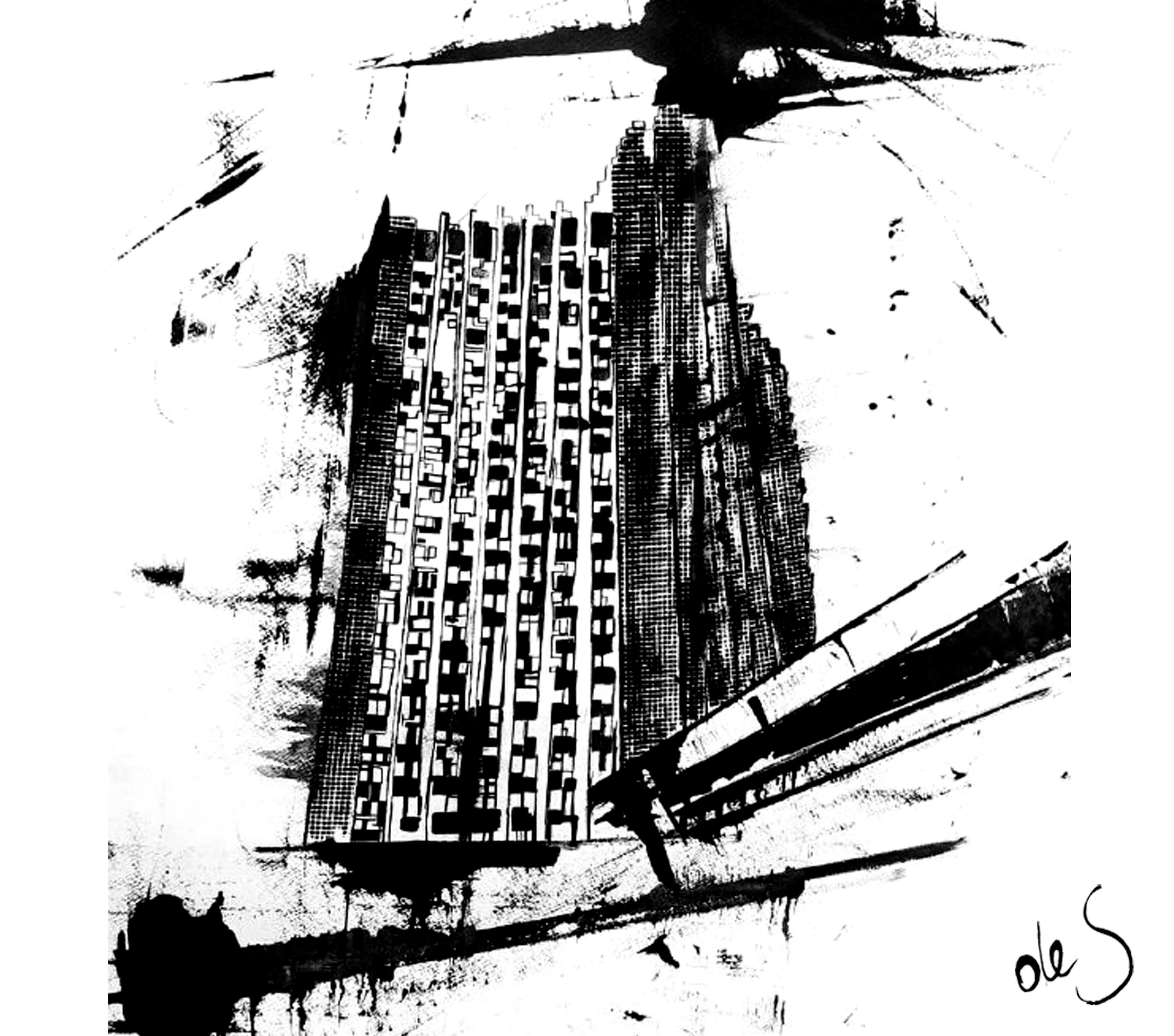

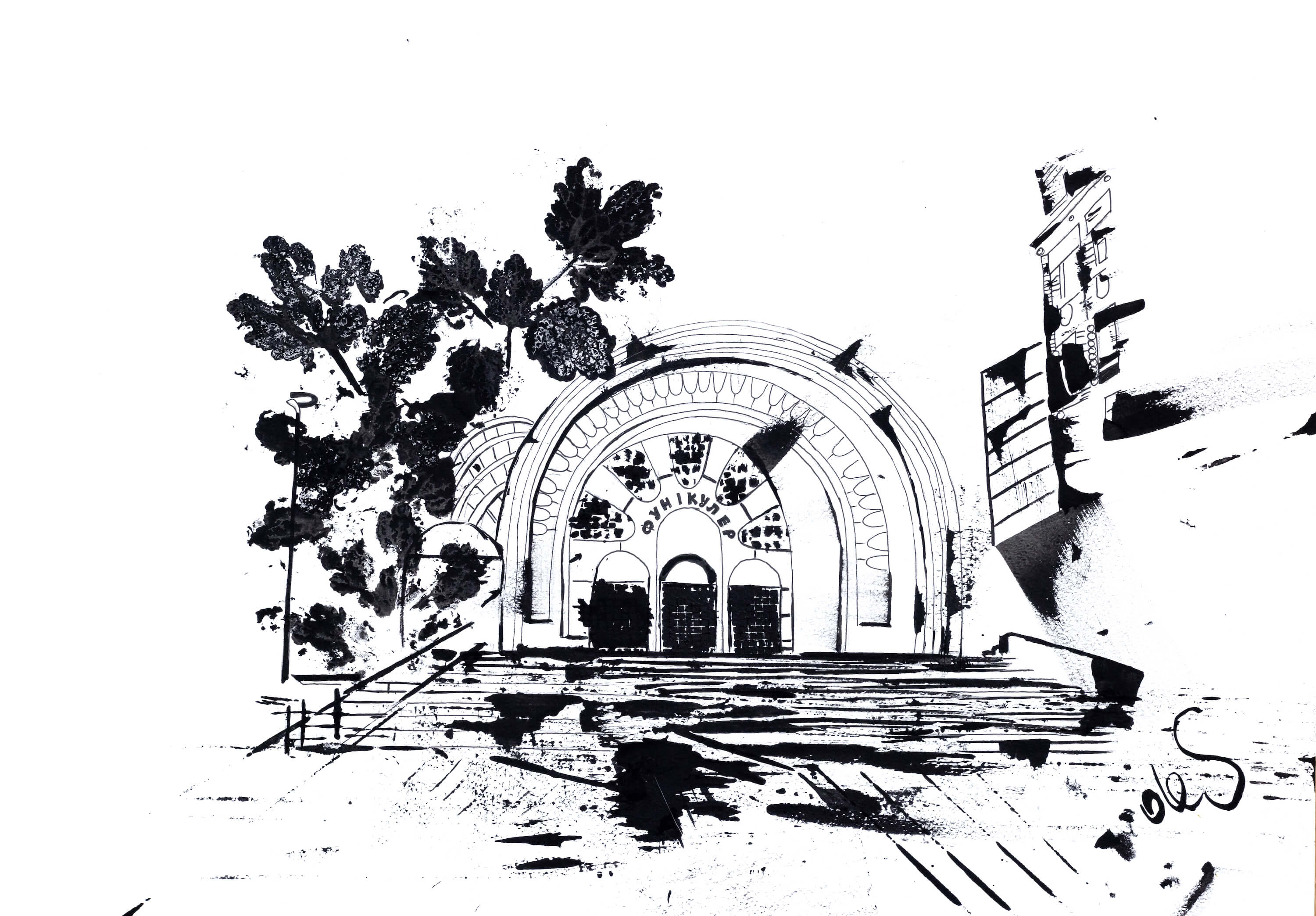

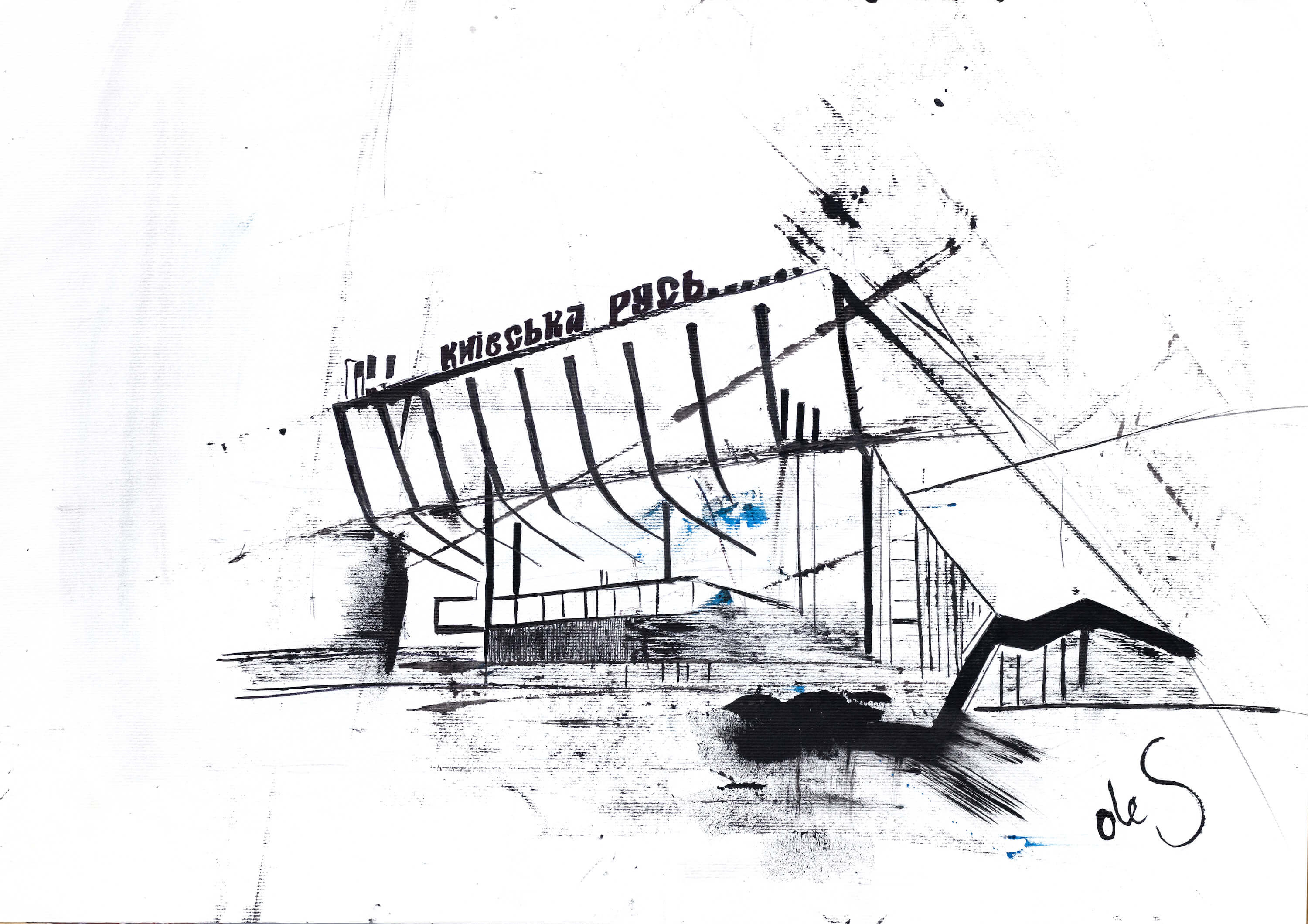

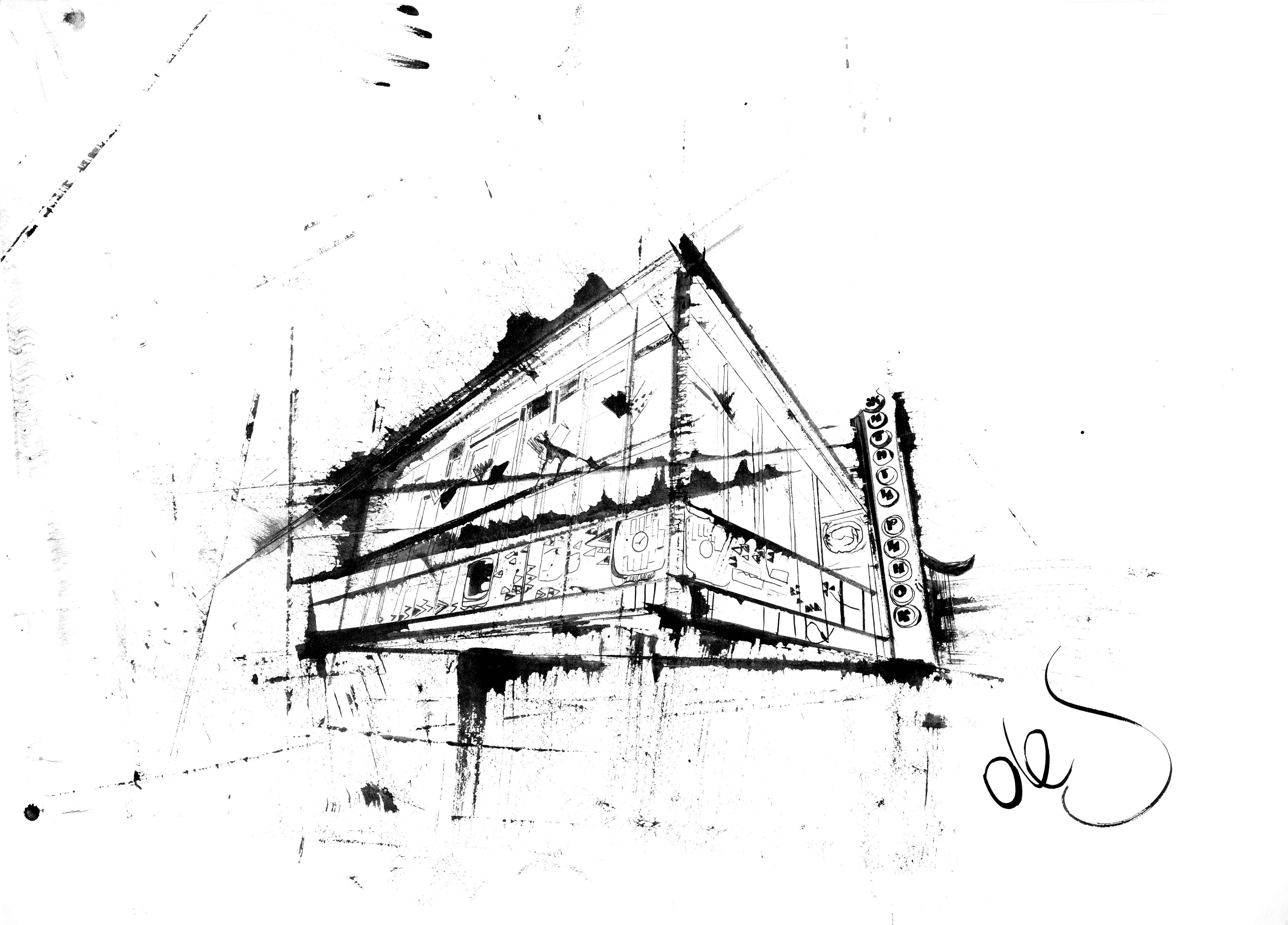

The Reciprocity project included my works from the Kyiv Modernism series that happened by sheer miracle. A student I had once asked me to help with her architecture project. I suggested doing a project on Kyiv Brutalism because I used to study architecture history myself. The project took a lot of sketching. I was never taught to draw, but I enjoyed making sketches. I made them intuitively, in my characteristic style — quickly, expressively, and with lots of inkblots. I liked the result, and I decided to develop the topic myself. The Kyiv Brutalism imagery was not exactly mainstream at the time, so I anticipated the trend to some extent.

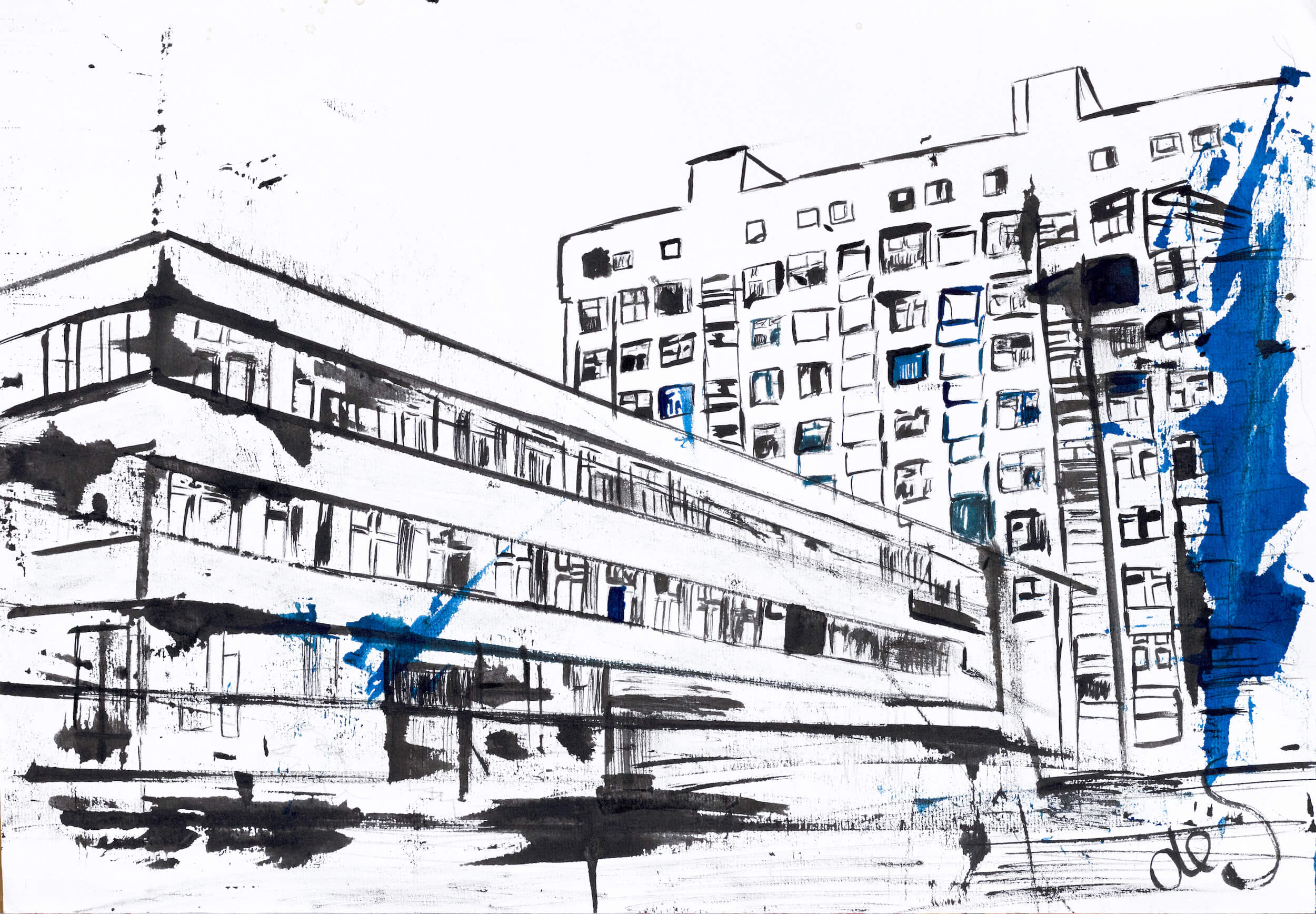

Kyiv Modernism strikes me as a combination of dullness and grandeur. And I’m not surprised the style rose to prominence — we just have no alternative. Now, a new generation has grown up, looking for something exciting and special for themselves. Kyiv Modernism fills the vacuum, and it will not lose its appeal until we have new acclaimed names in contemporary architecture. There is nothing Soviet about it, although it was conceived in the USSR. These buildings look stylish even now and blend in well with new installations.

There is nothing Soviet about it, although it was conceived in the USSR.

I like it if a building has a history of its own and there is some mystery or intrigue about it. That architecture that is just grand and beautiful is of no interest to me. Meanwhile, Kyiv Modernism is full of disturbing and turbulent stories, and now it goes through another one. I remember visiting the Kyiv Crematorium when I was young and how it occurred to me that architecture reflects its author’s life, even if it is commissioned work. These buildings are as powerful, thrilling, and complicated as their authors.

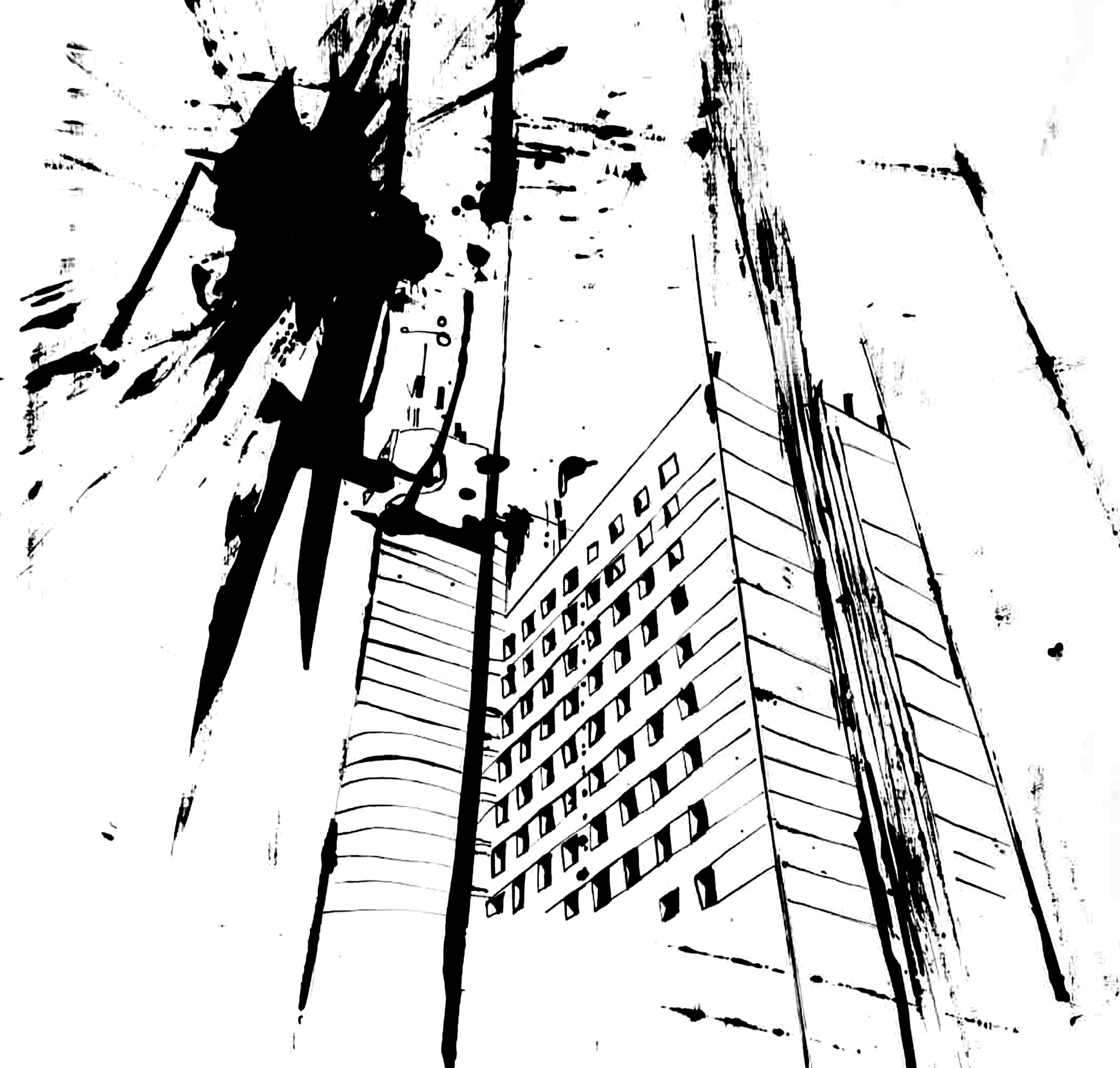

The war makes us see our cities from a different angle. We managed to preserve Kyiv, but look at other cities: Mariupol, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, and others in the East of Ukraine. They turn to dust. The same could happen to Kyiv. Often, foreigners see the Tarilka building or the Salute Hotel in my drawings and go, “Hey, it’s Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine”. I dread to even think that these buildings could disappear. I feel that my role as an artist is to show people what we could lose during the war.

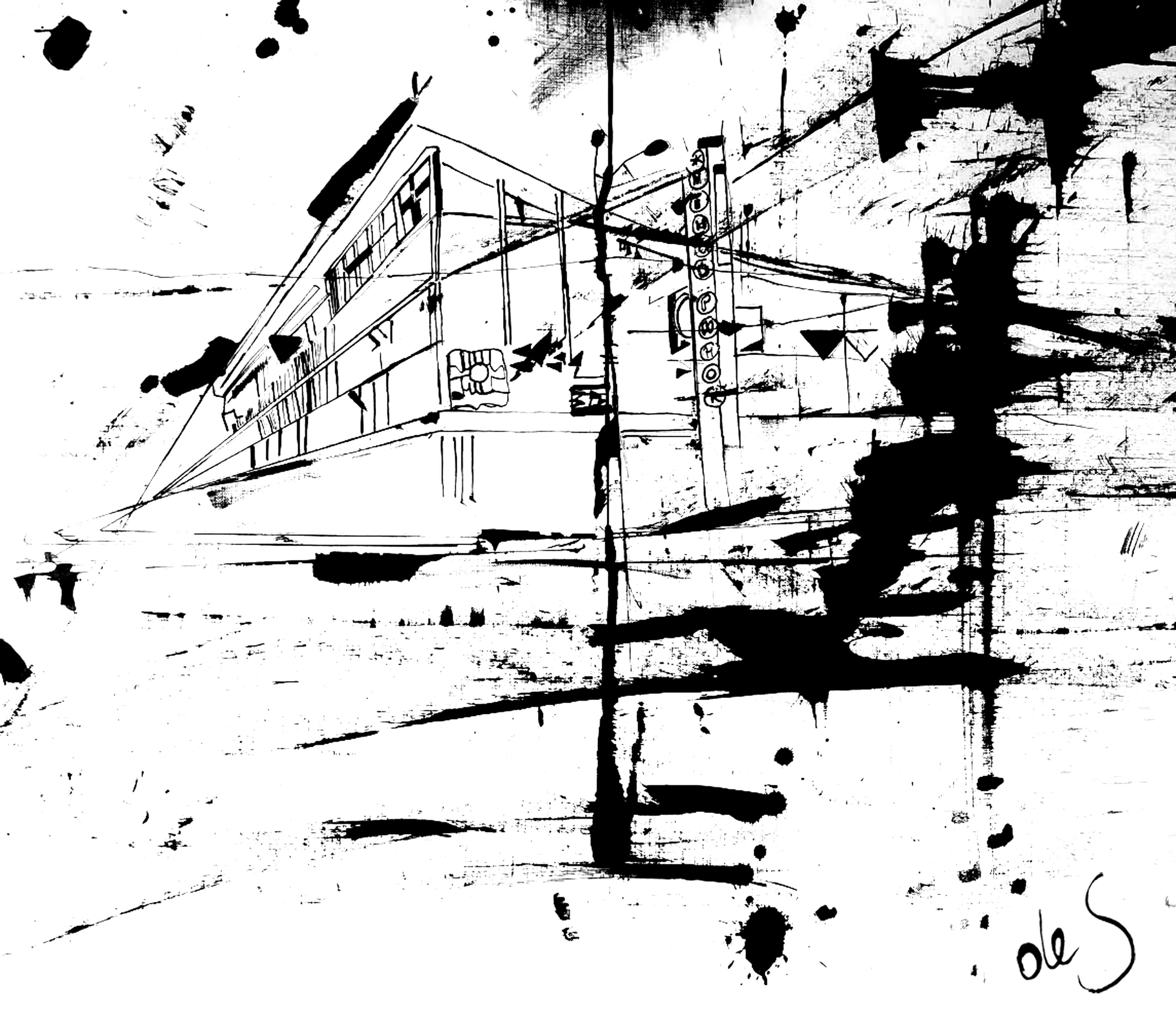

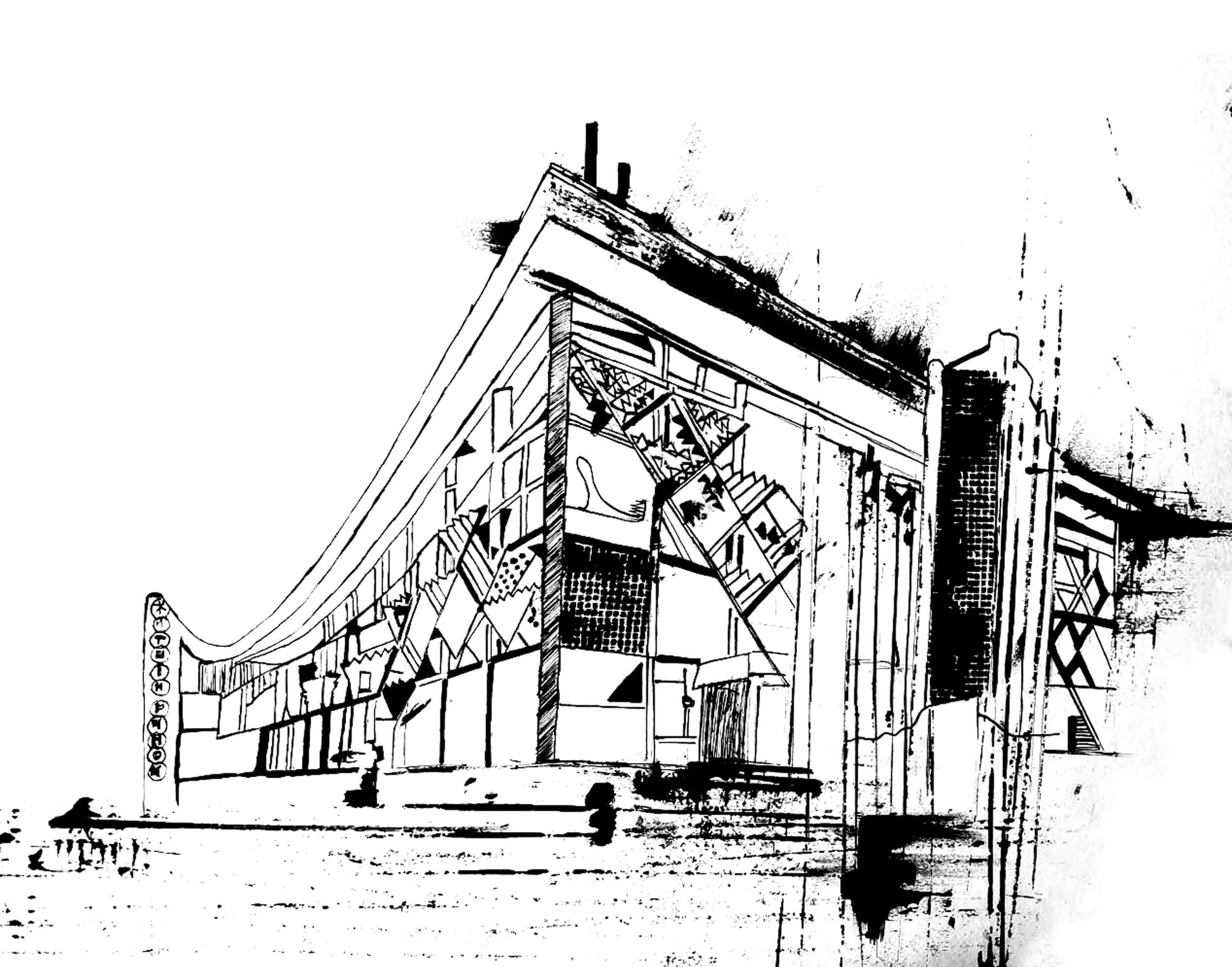

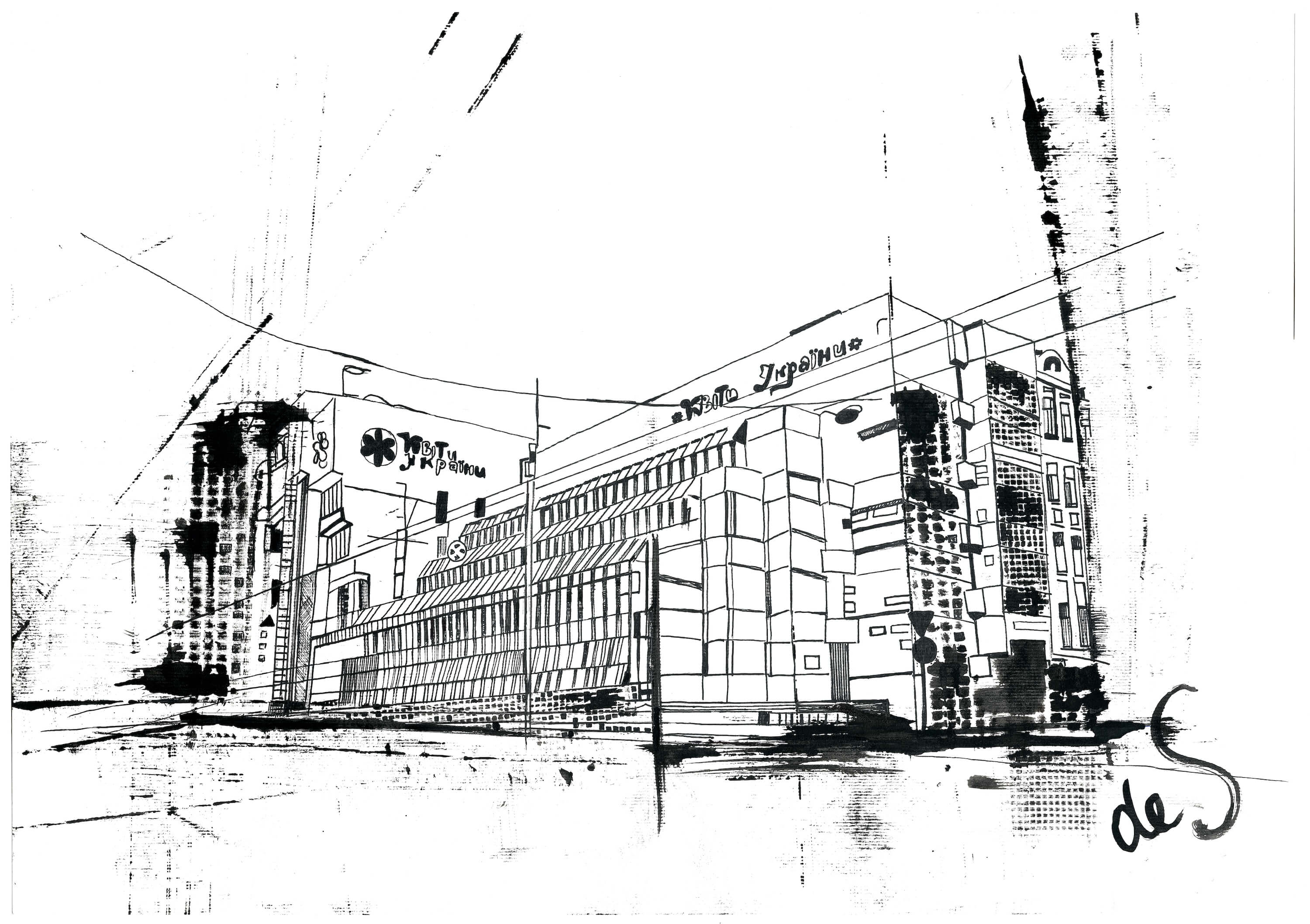

It was the war that pushed me to draw the Flowers of Ukraine building. I visited it in my childhood, but the building didn’t look as impressive as the Kyiv Crematorium to me at the time. Still, it was much discussed, the mass media were abuzz about it, and I started to think about it more often. Because war is noise, after all.

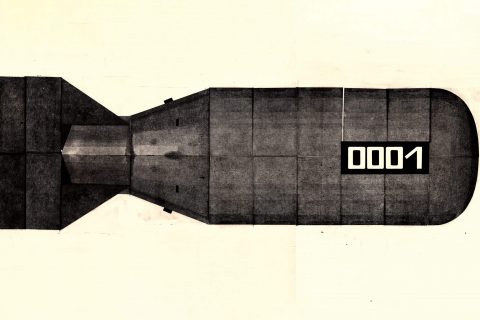

The Antonov Airplane Factory is another excellent example. It is one of my older works, and it was purchased for a private collection in Sweden. Like the Flowers of Ukraine, the factory’s building was in jeopardy, but for an entirely different reason (the Antonov plant came under shelling in March. — Ed.).

I have mixed feelings about the destruction of buildings depicted in my drawings. On the one hand, it’s sad. On the other hand, it could be seen as a manifestation of their intenseness and transience, fatalism and beauty. I hope the war will make us reconsider our relationship with architectural landmarks, which often turn into ruins or shopping centres. Perhaps, we will become more mindful of them.

Still, I hope the war will make us reconsider our relationship with architectural landmarks, which often turn into ruins or shopping centres.

I am working on a new project now. It will be focused on buildings destroyed during the war. I want to draw them as they were before the 24th of February and as they are now. I want to capture the damage and remind people that we should value and cherish our cities, buildings, and history.

New and best