Paradoxical War and Air-raid Sirens in Lyusia Ivanova’s Paintings

A Ukrainian painter born in Dnipro and based in Kyiv. She graduated from the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture and works with paint, sculpture, video, textiles, land art, and environment art.

— My exhibition was set to open in Dnipro on the 25th of February. I was looking forward to it so much. Over the previous 18 months, I created a lot of paintings connected to my native city. In my thoughts, I wandered its streets, reflecting on various episodes of my life, various symbols, scents, and even urban legends about the man-eater catfish. What I saw on the news the day before made me realize how inappropriate it was, but I still wanted the exhibition to happen. My 24th of February began not with exhibition preparations but with a trip to the grocery store at 6 AM. Now I believe that the decision to go to Dnipro was fateful because it let me be closer to my family. I spent over 40 days there.

I didn’t start painting again until two weeks into the invasion, which felt like years. Over that time, I totally forgot that I had a body at all, that I was an artist. It was like my entire background and self-conception were erased. It felt like the end of everything, and I didn’t think about what lay ahead. However, when I realized that our country wasn’t taken in a few days and we still had an army and a future, it gave me the strength to start working again.

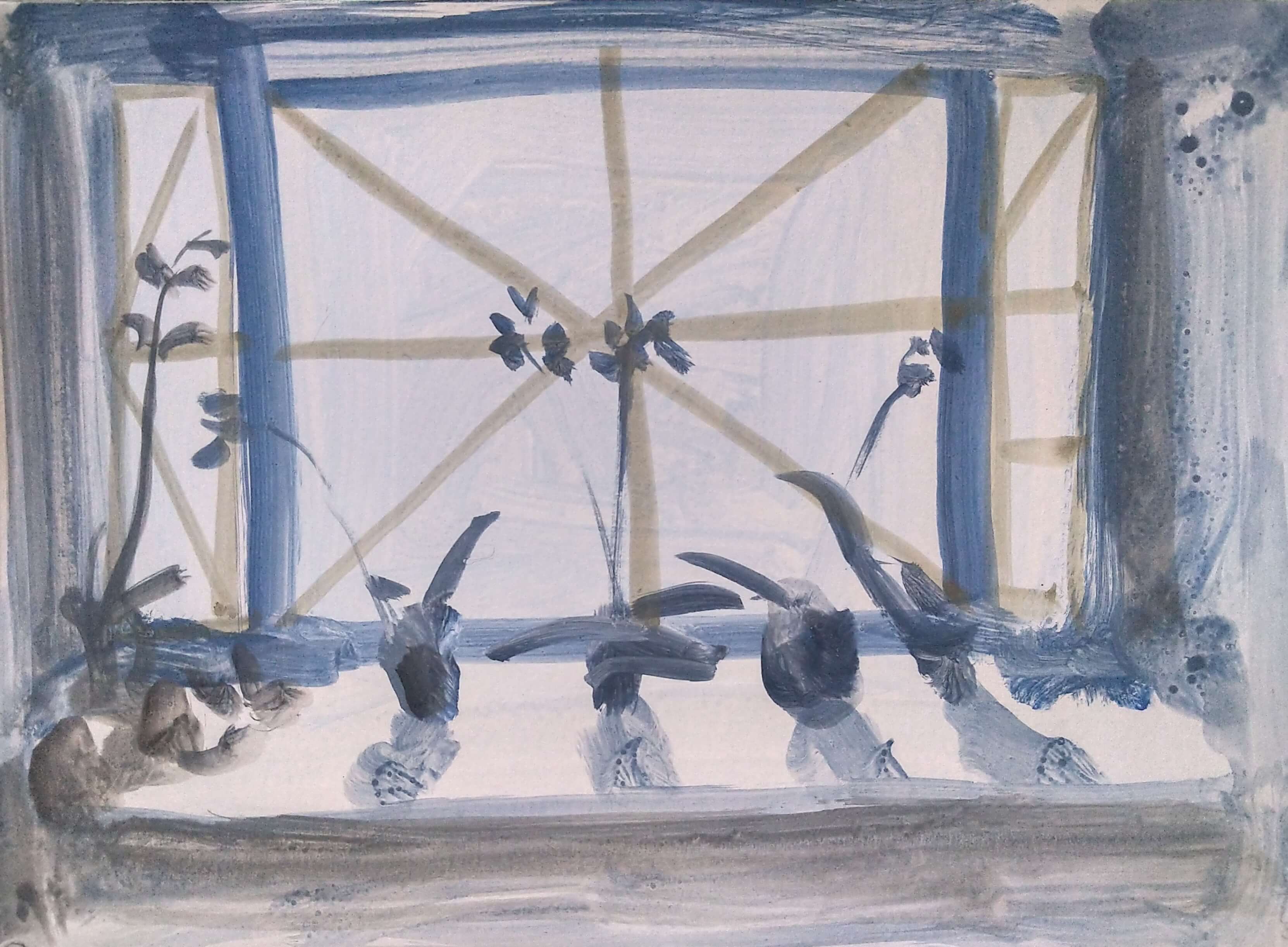

It all began with everyone stopping to take photos not to be mistaken for saboteurs. However, I wanted to document what happened around me. Dnipro froze in tense expectation. Everyone understood that it was war, but the city was still unaffected outside of a few missile strikes and injured people being brought there. It was paradoxical. So, I decided to document this state of expecting a catastrophe. The series with suspicious figures and landscapes was created after those strolls around the equal parts peaceful and tense wartime Dnipro. The first attempts to return to painting brought some relief — it was as if I had returned into my body.

Dnipro saw no active hostilities. It was paradoxical. Therefore, I decided to document this state of expecting a catastrophe.

Window with suspicious view

Suspicious man approaches me

Landscape with a suspicious person

Wartime landscape that is too quiet

Air alert

Wide awake during an air-raid alarm

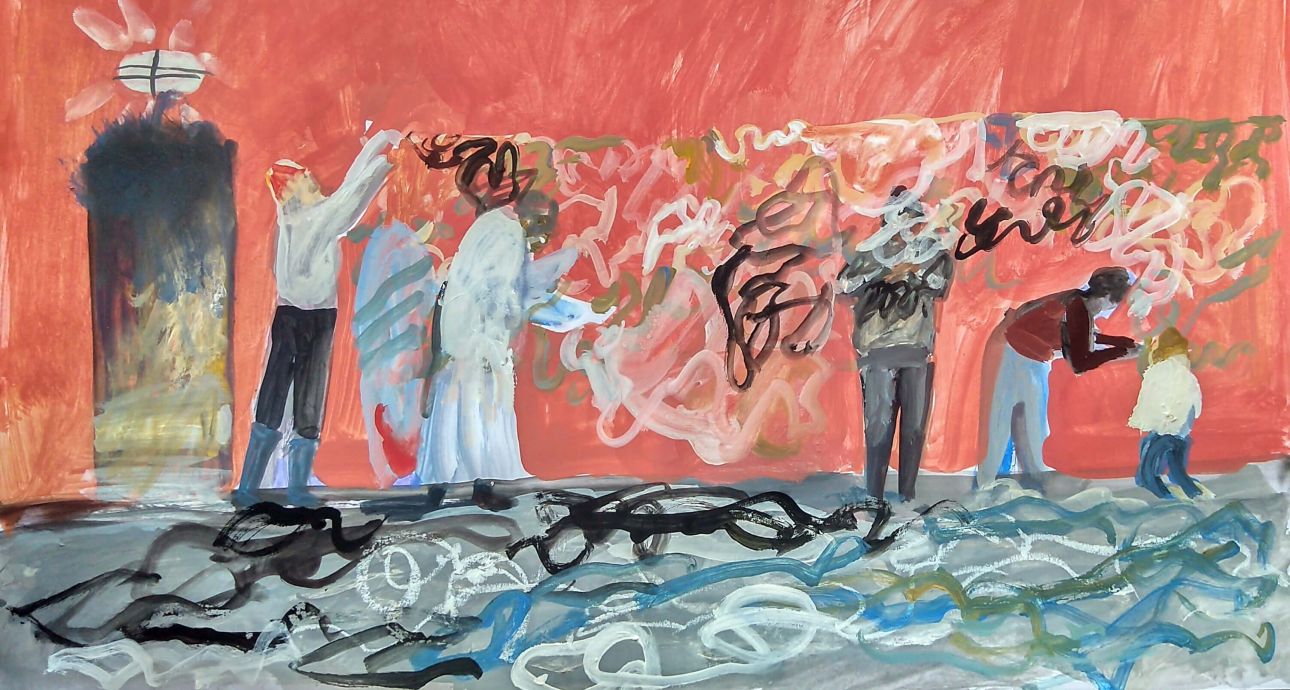

I went to help weave camouflage netting. Working to provide concrete help calmed me down. Besides, handiwork with coloured fabrics was a meditative experience. The net had to be made so as not to look artificial, avoiding straight angles, imitating nature, and being aware of how it would look from the plane. It was an exercise in land art and even pictorial art, in a way. A multidisciplinary thing of sorts.

Painting is not something that calms me down — it’s a different kind of process that takes intellectual effort.

The weaving of camouflage netting is an exercise in land art and even pictorial art, in a way.

The Maidan was a pivotal moment for my understanding of art and the artist’s purpose — I came to the conclusion that art needs to be free from any obligations or higher purpose. However, now I believe that if you are a public person doing art, your every work becomes a statement under the current conditions. You can’t stay out of politics nowadays. Culture is an impactful weapon, and it becomes even more powerful if we are unaware of that. I mean, if we are unaware of some other culture’s influence on us, we can fall its victims.

If you are a public person doing art, your every work becomes a statement under the current conditions.

I would like to be more straightforward in my art now, but it contradicts my feeling about what and how I can do. I have ideas for some very poster- and comic-like pieces now and then, but they remain unrealized. Photography and video are the most potent mediums to document Russian crimes and Ukrainians’ suffering these days. I feel I have no right to interpret it in art. I can’t use documentary images literally in my work. For me, it’s unethical and manipulative. Besides, depicting pain and suffering openly would be a pretty arrogant thing to do. I don’t deny anyone’s right to do that — it’s just a decision I made for myself.

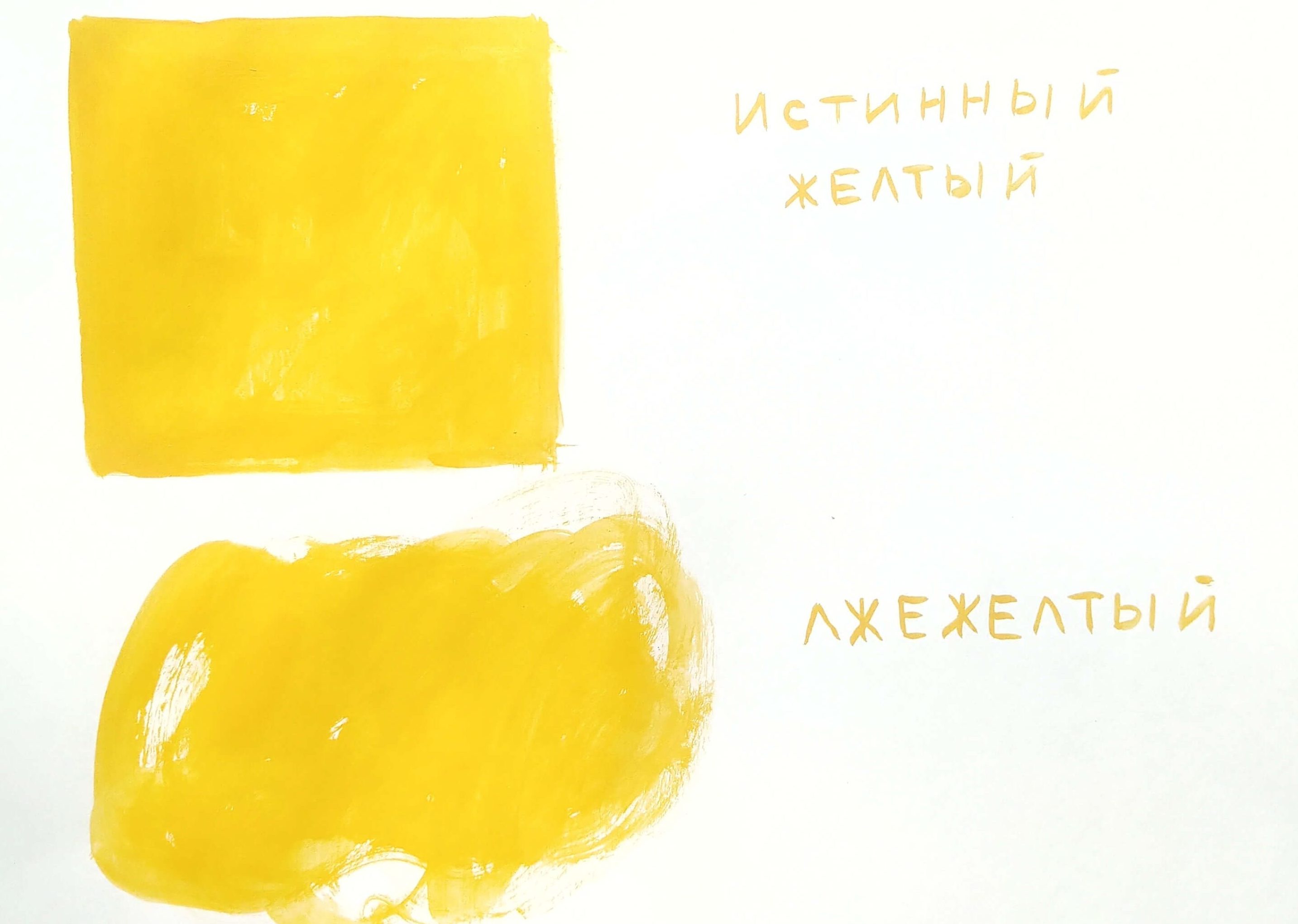

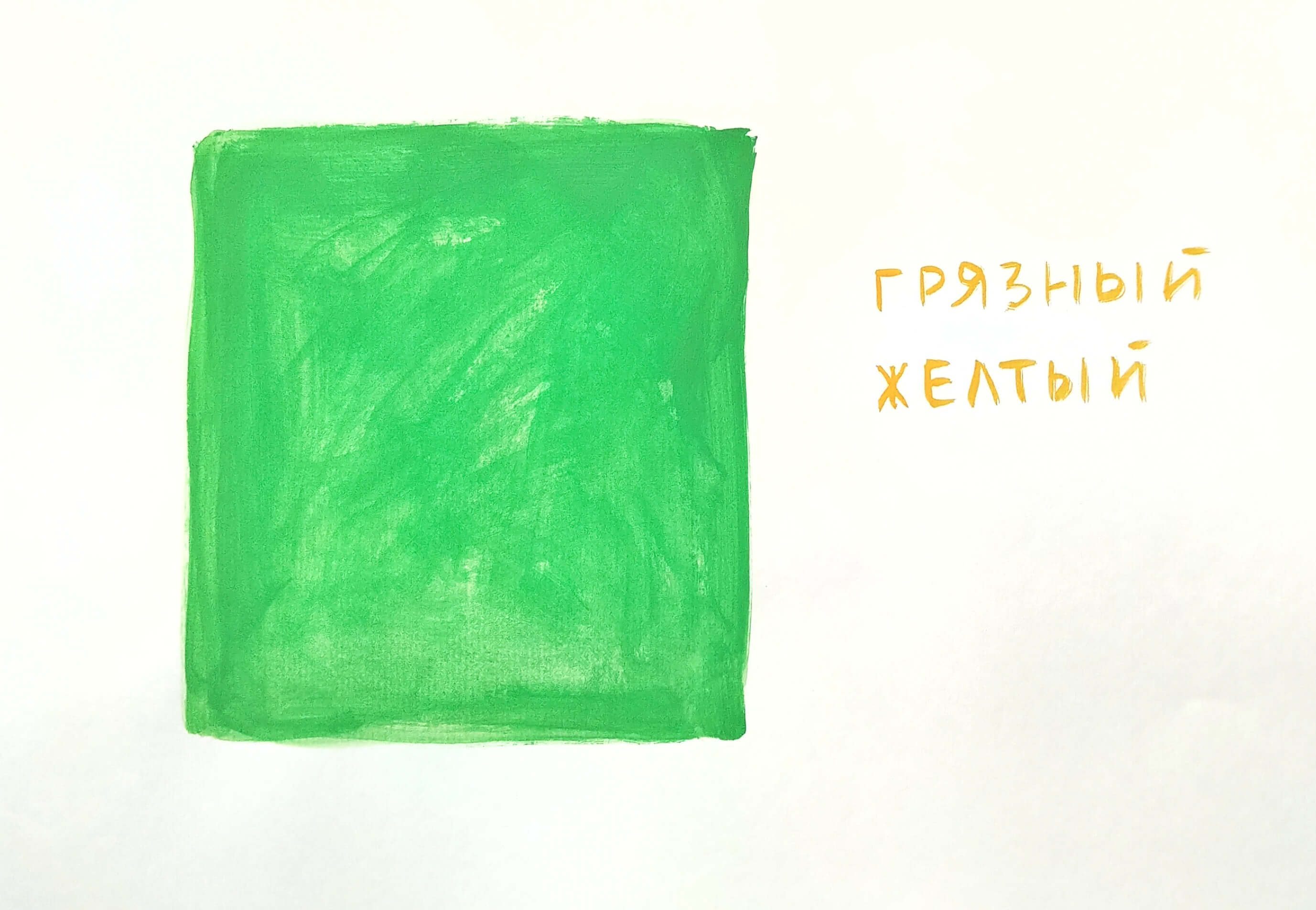

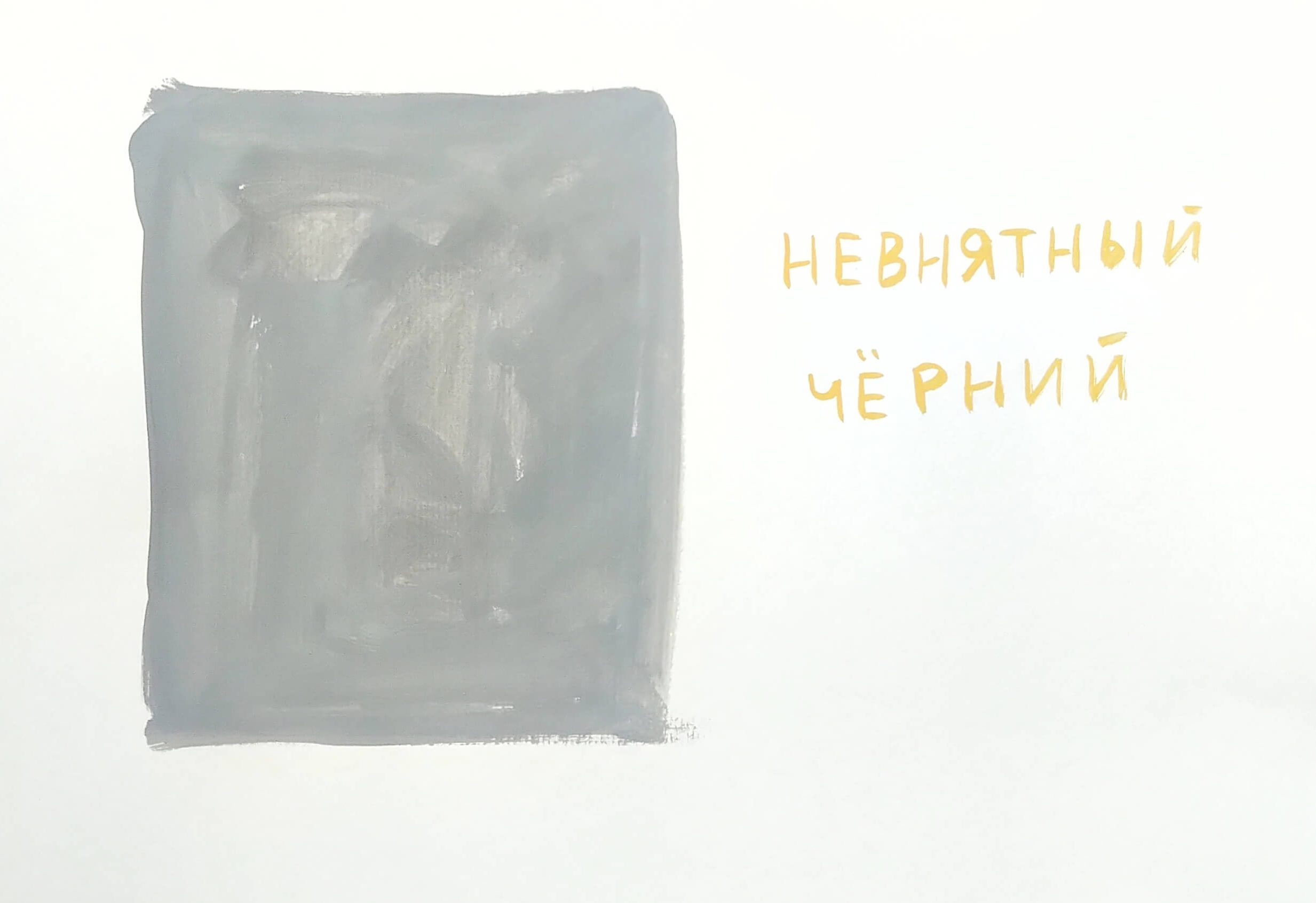

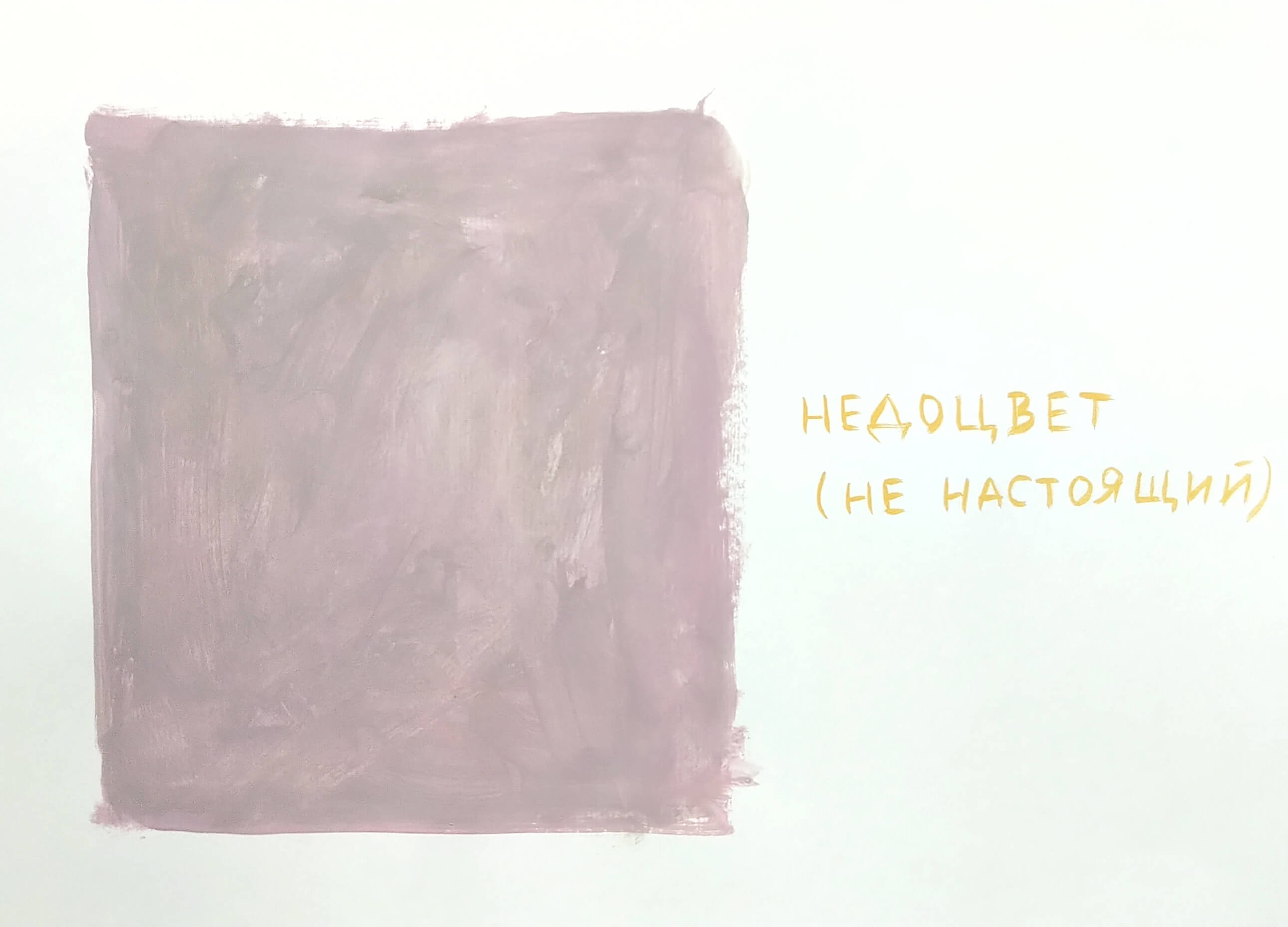

Still, I have made a statement with my [Exercise in] Colour Repression series, even if not directly but analytically. I have relatives in Russia, but there is no dialogue between us — I don’t even know what stance some of them have on what is happening now. All this time, I wanted to make something about propaganda, which has become key to the Russians’ lack of understanding of the situation and empathy. This Colour Repression series of mine is like an absurdist cartoon showing the manipulative nature of propaganda on the example of the yellow colour. I’m unsure if it will be seen and understood by the people I’d want to, though.

Then I left Dnipro for Venice. There, I started taking photos again, wishing to somehow appropriate the surrounding beauty. However, it made no sense for me to paint something that was just beautiful. It occurred to me that I started noticing beauty only after I caught myself thinking something like, “Hey, it’s not a drone — it’s a seagull”. Therefore, I decided to capture the moments of looking for danger in everything, which grew into an entire series of paintings.

One of them — the one with a night sky and glowing tower — was created later in Vienna. Here, my flat’s windows overlook an amusement park. So I have this war inside, and then there is that park working non-stop in front of me, with all its bright colours, the sound of an air-raid alarm, and noisy people.

Entertaining park, not suffering crying

Fallen leaves, not people

Owl light, not curfew

Evening cloud, not azote

Seagull, not drone

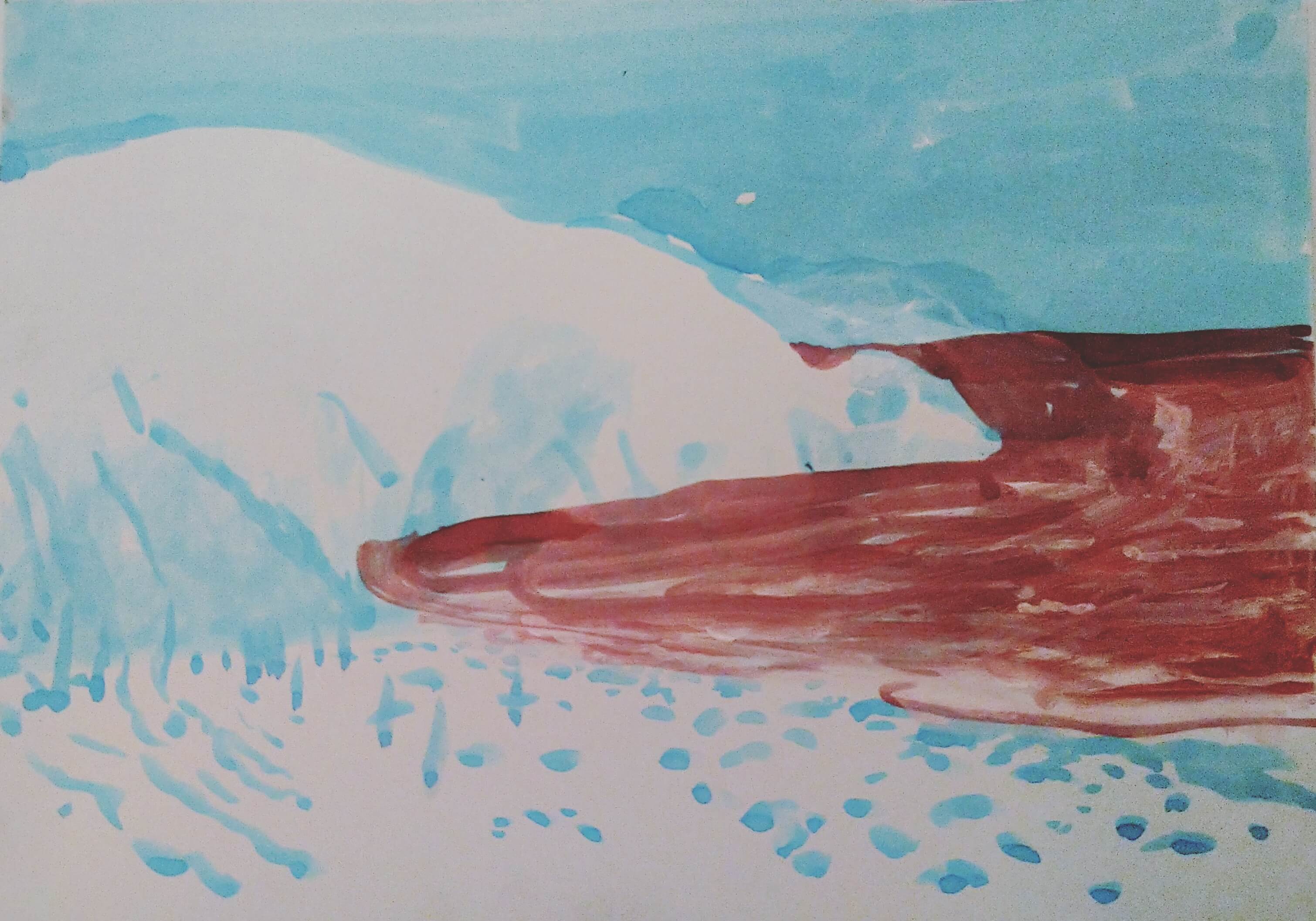

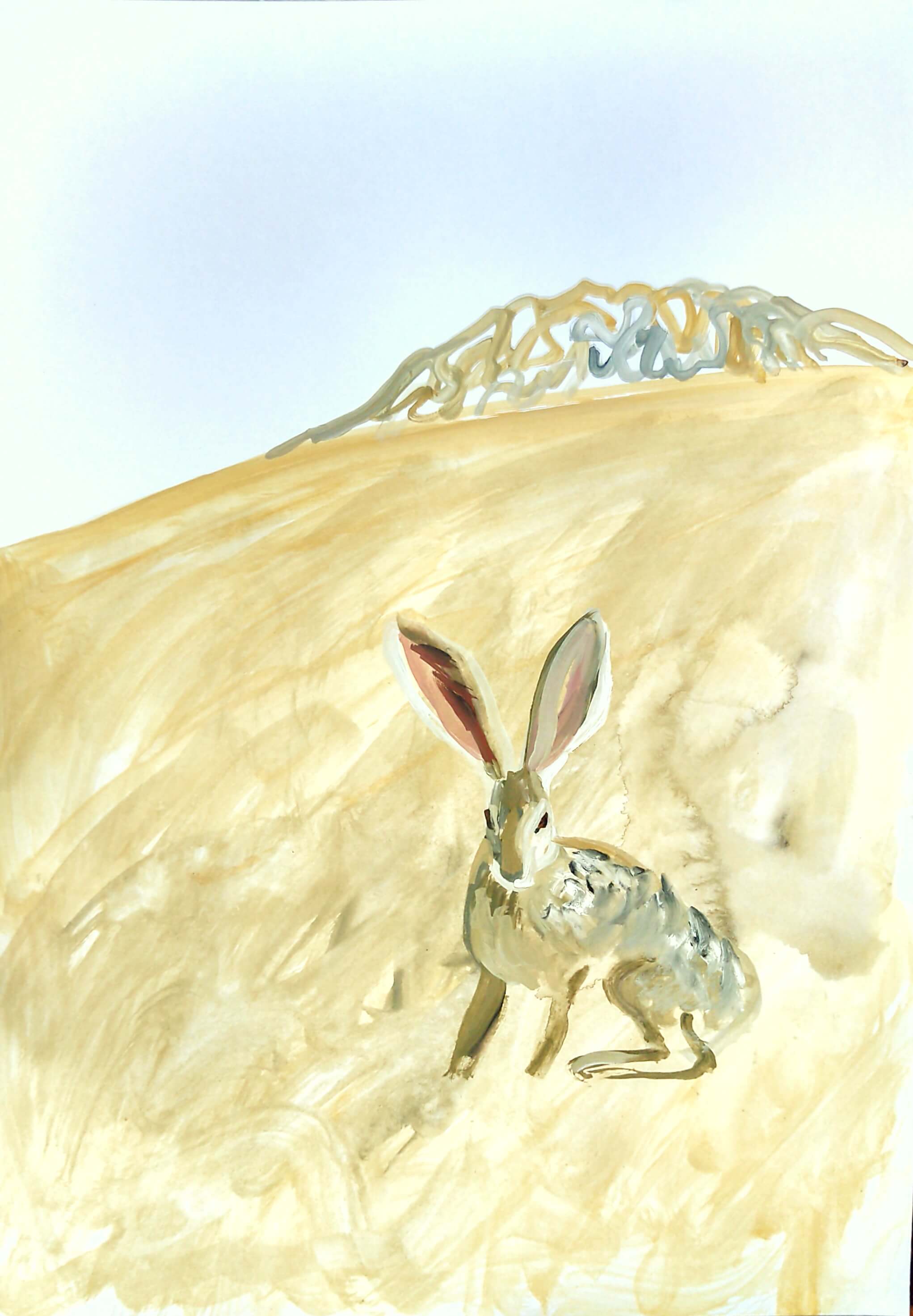

Drinking Bear is a pretty straightforward piece, too. We all get that it’s the Bear Mountain in Crimea — the bear that should drink water but drinks blood. After all, so many people gave their lives to enable water supply to Crimea, among other things. Meanwhile, the Checkpoint Hare is a real animal. I didn’t see it myself, though. Someone who built those checkpoints told me about it.

Drinking Bear is a straightforward piece. It’s the Bear Mountain in Crimea — the bear that should drink water but drinks blood.

Everything depicted in my wartime works is an integral part of my life. On the one hand, I want to forget it. On the other hand, however, I will always discover something about myself and draw conclusions reflecting on these memories. The war affected my technique, too. All my recent works are small-format and painted on paper because they are easier to move and store this way. Also, I now use tempera and acrylic paints because they take less time to dry.

Letters to Sisters is a self-portrait painted far from home, and the fish in formaldehyde is my way of releasing the stress of keeping silent. It’s like I’m having a conversation with my sisters in my head, although we rarely talk in real life. I posted these pictures on social media, hoping my family would see them and react at least in some way. They didn’t, but I felt relief, meaning it worked for me.

Drinking bear

Self-portrait. Letter to my sisters

Fish. Letters to sisters

Hare near the blockpost

New and best