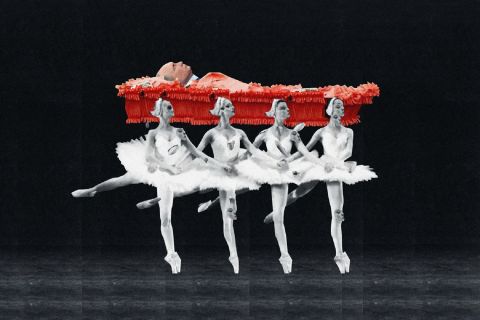

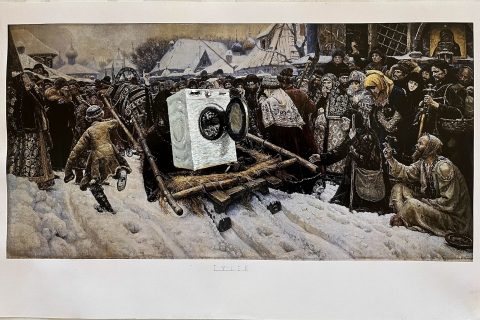

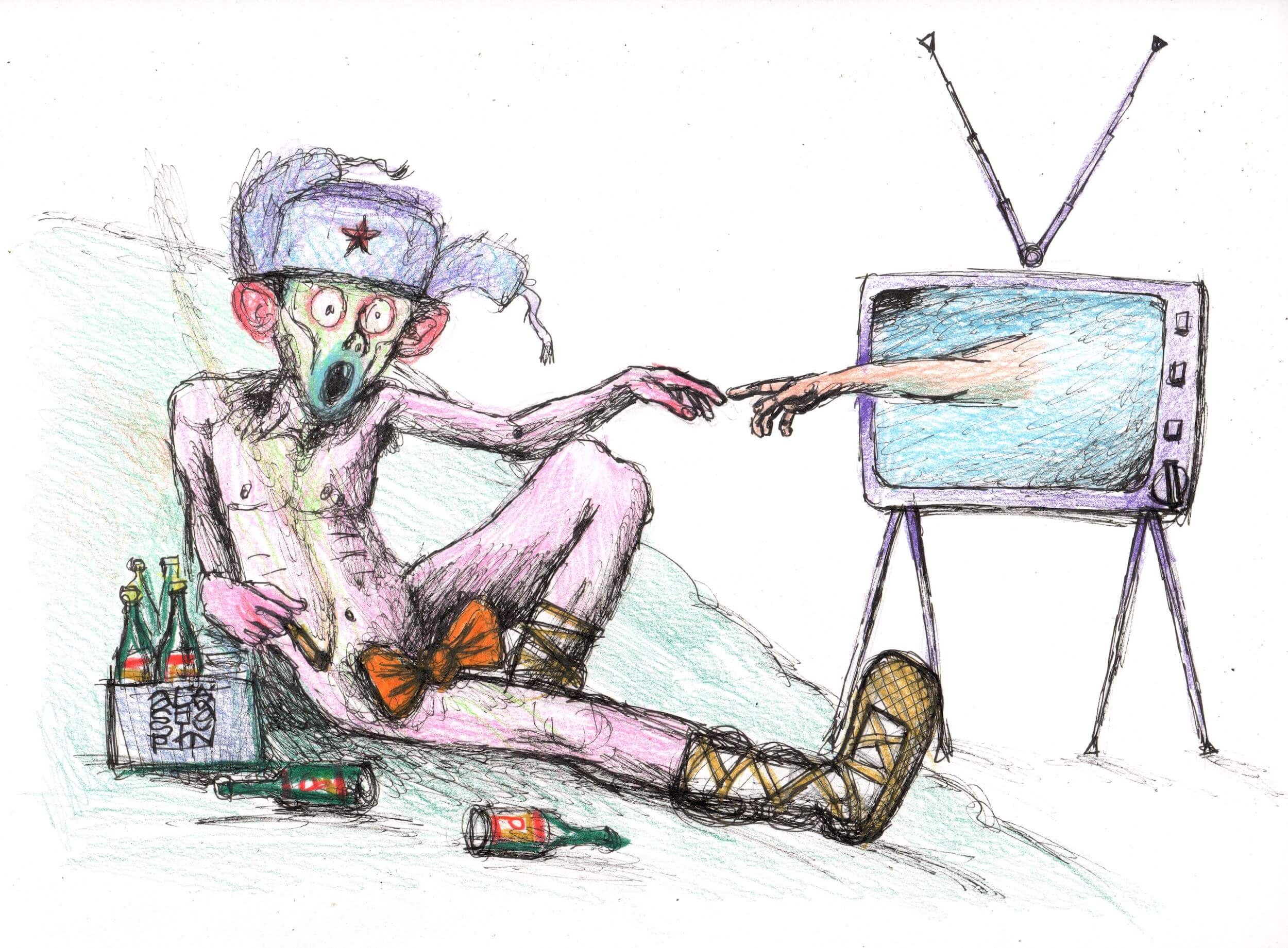

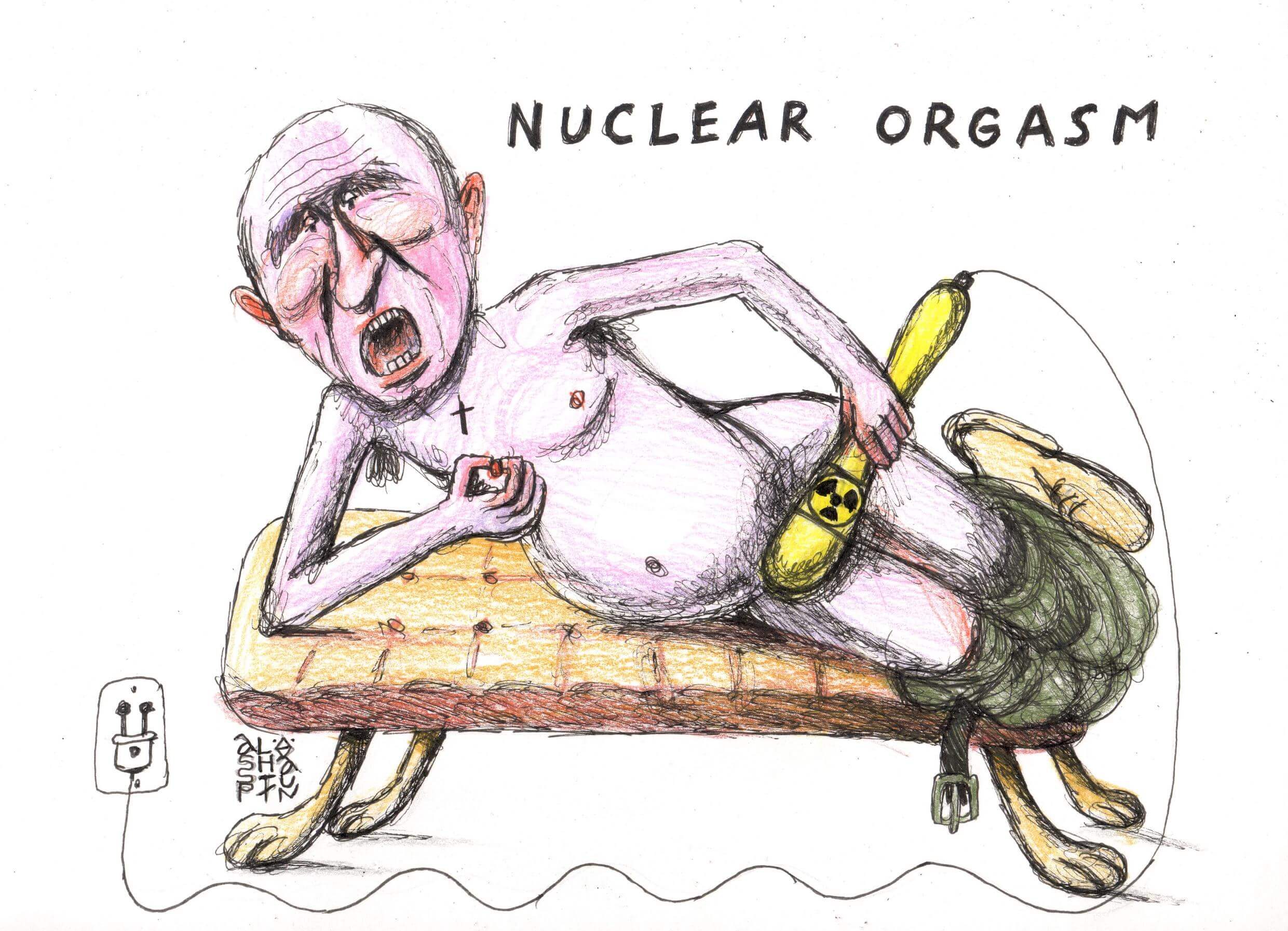

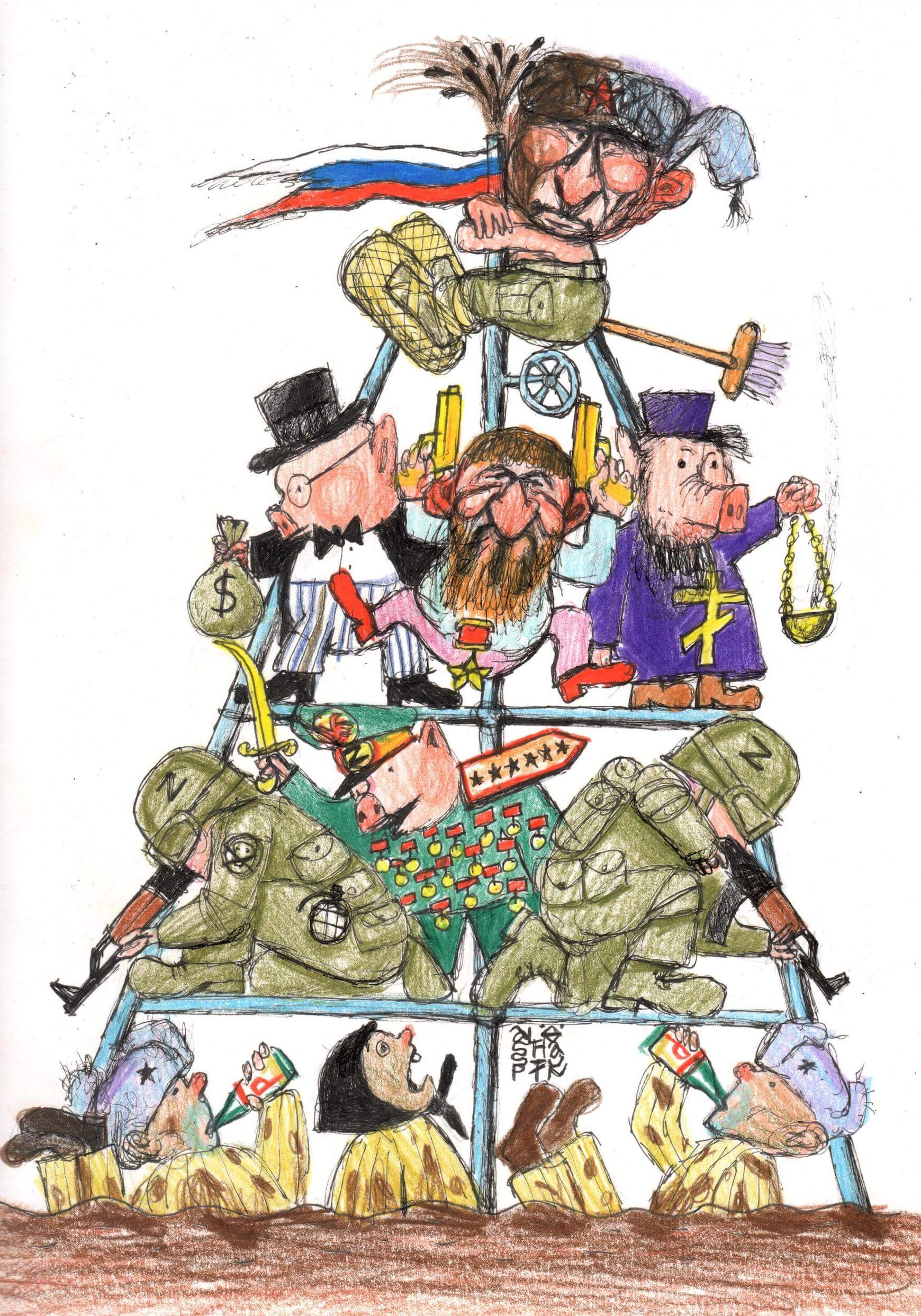

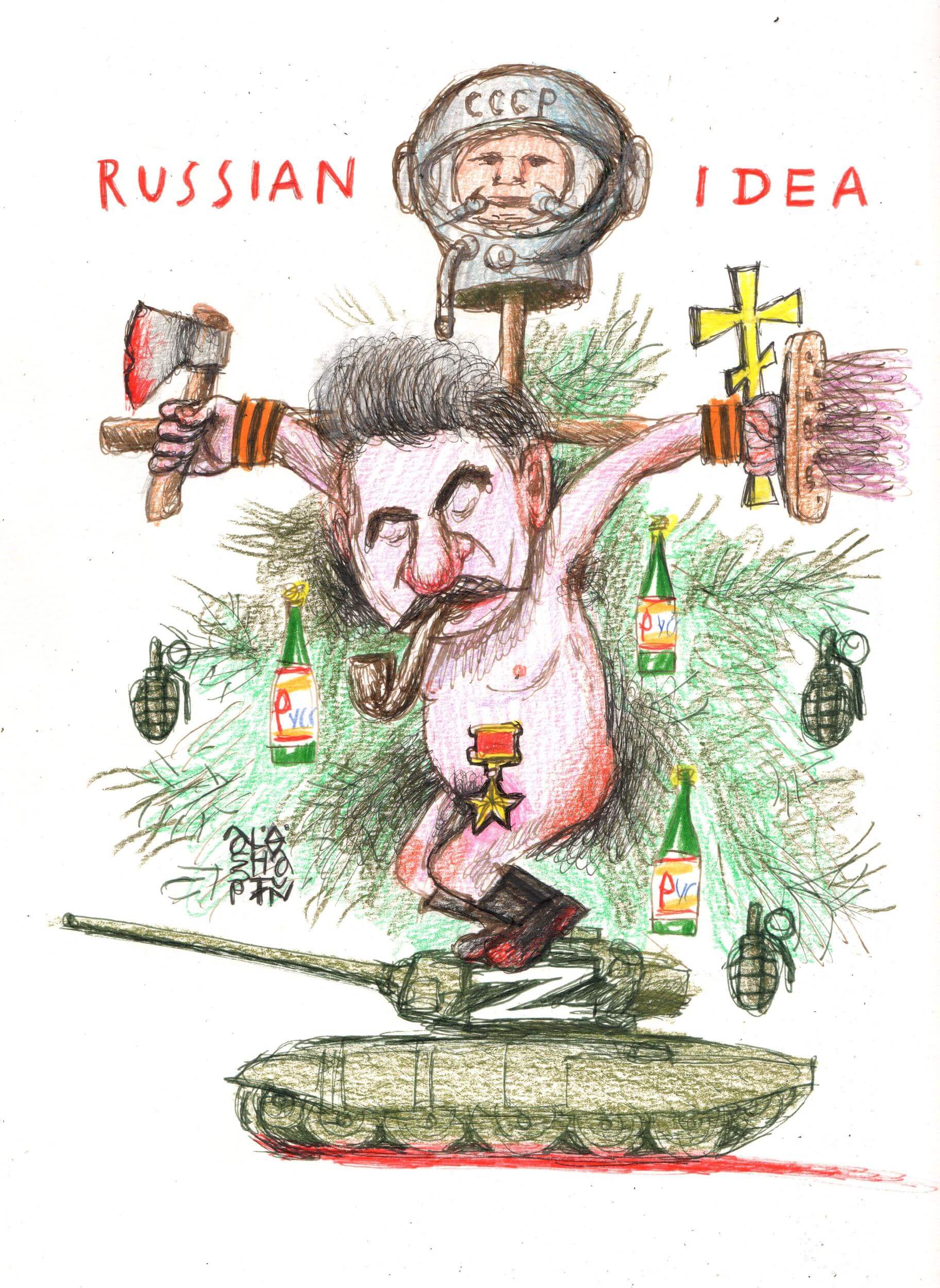

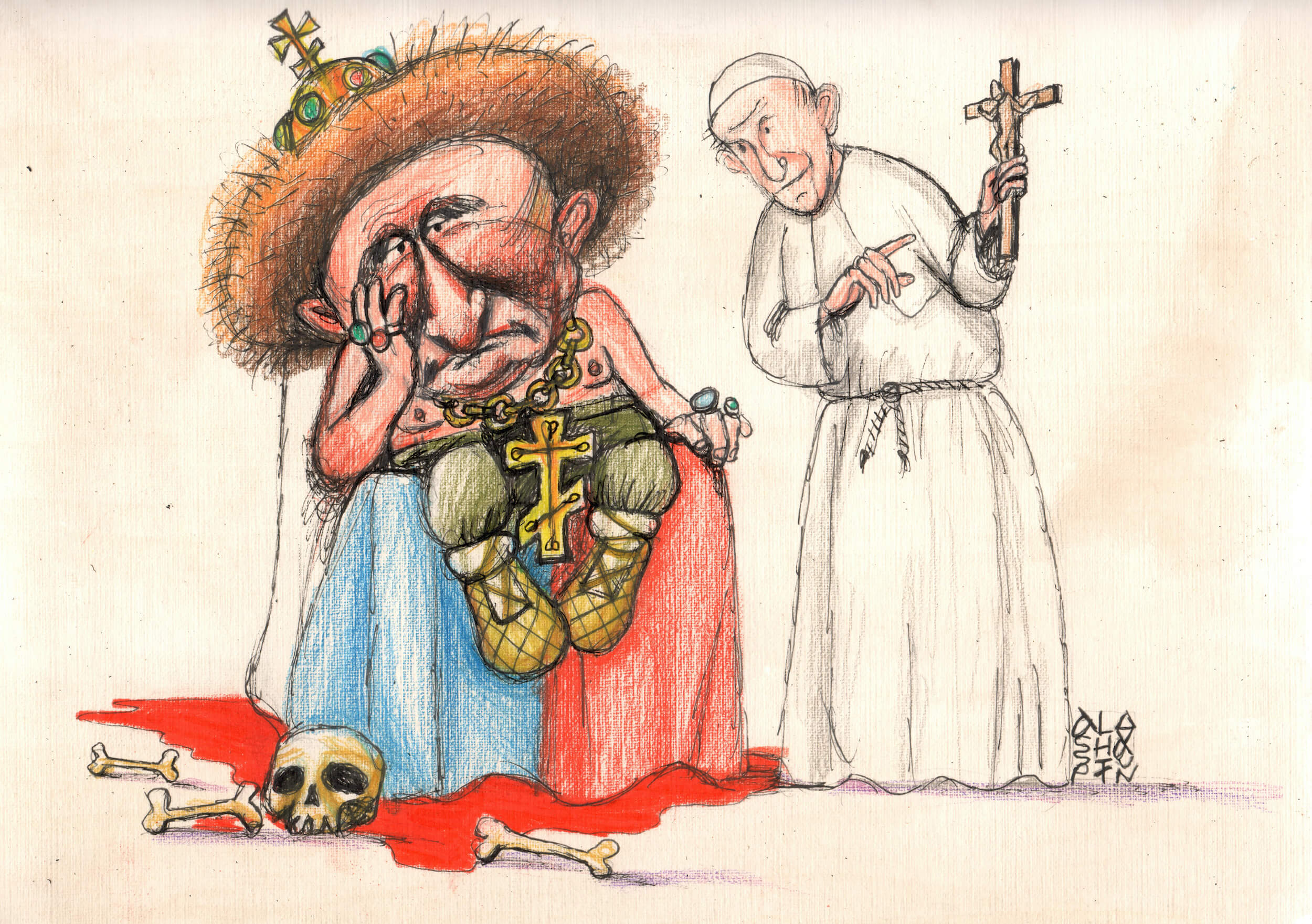

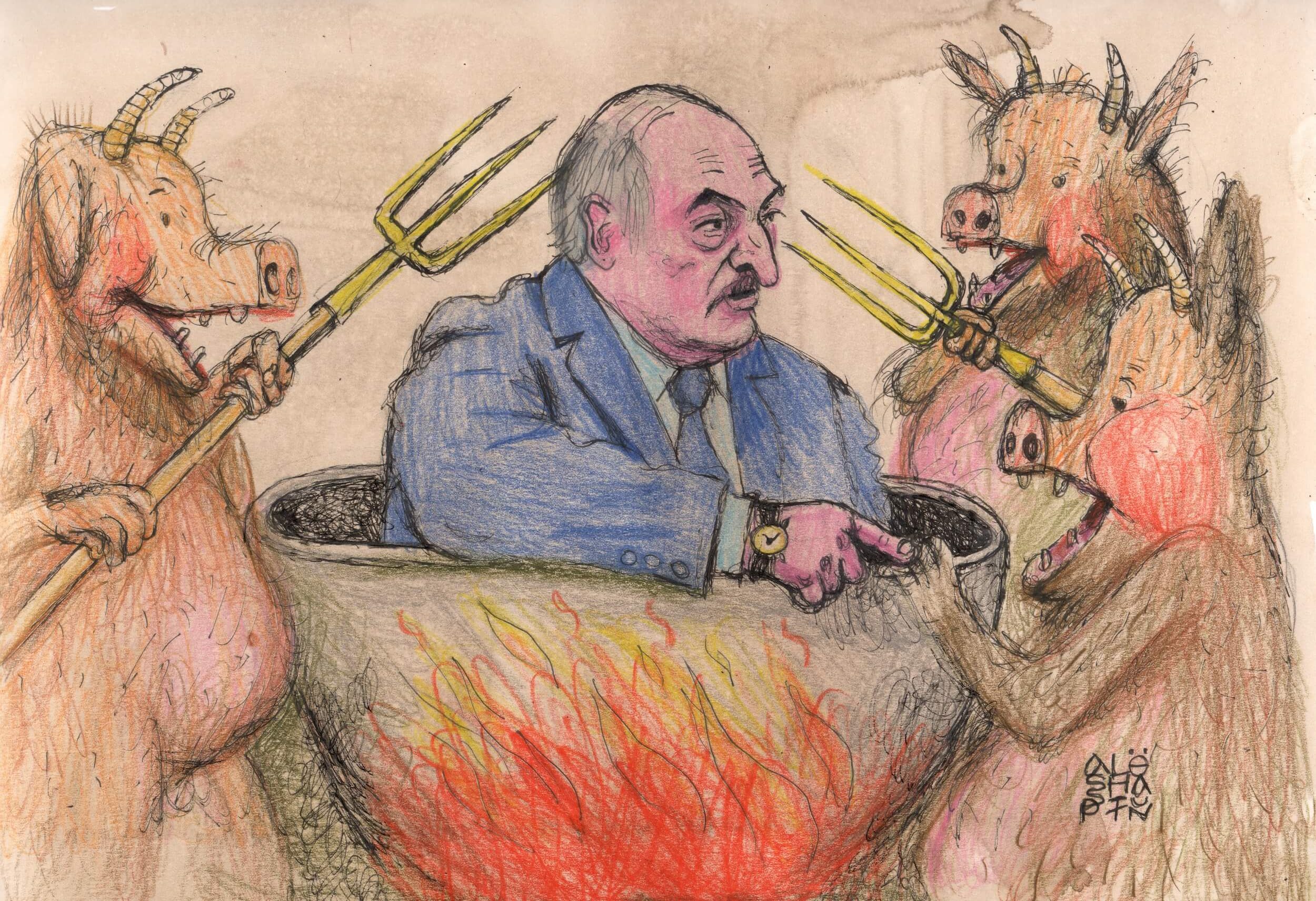

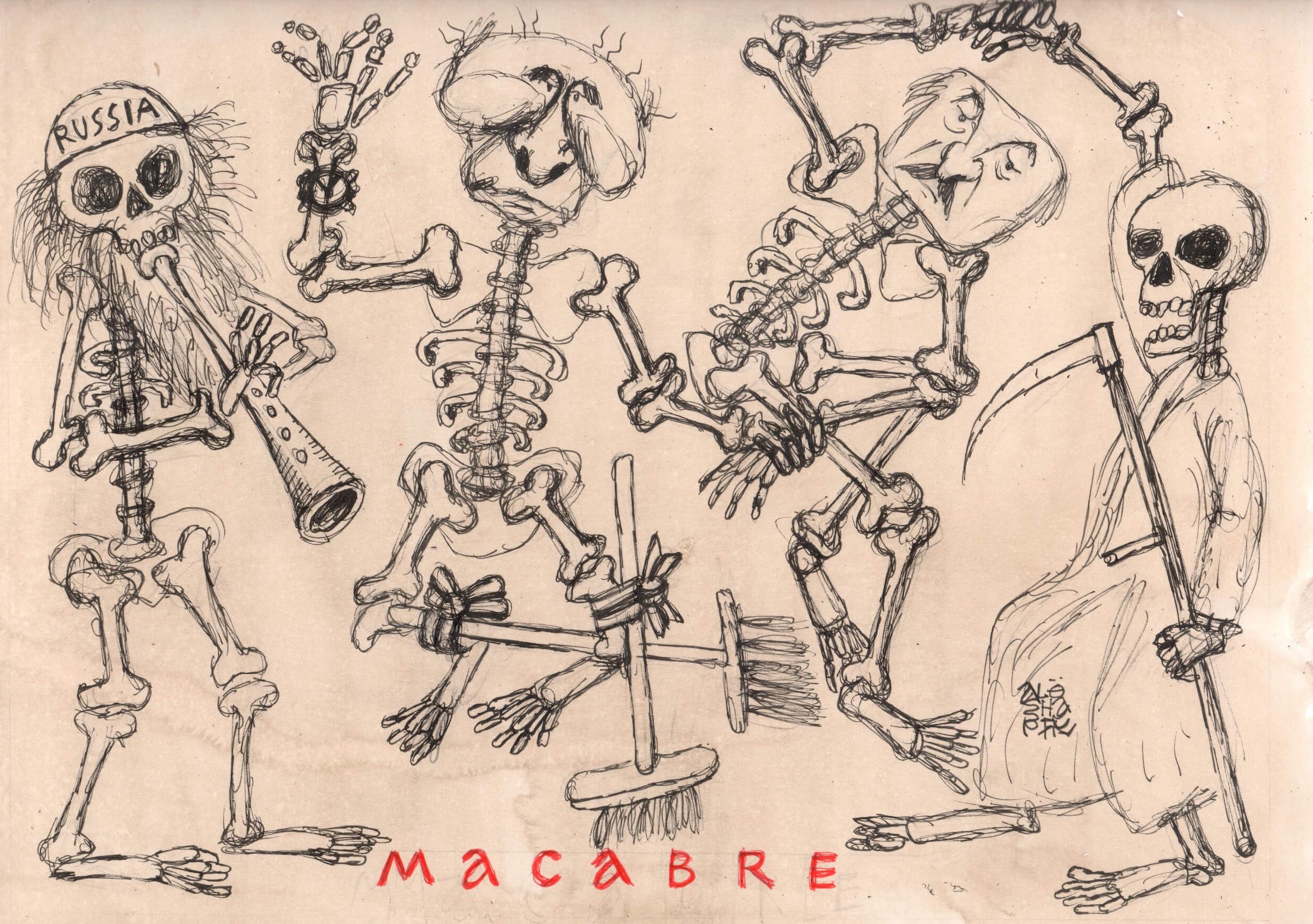

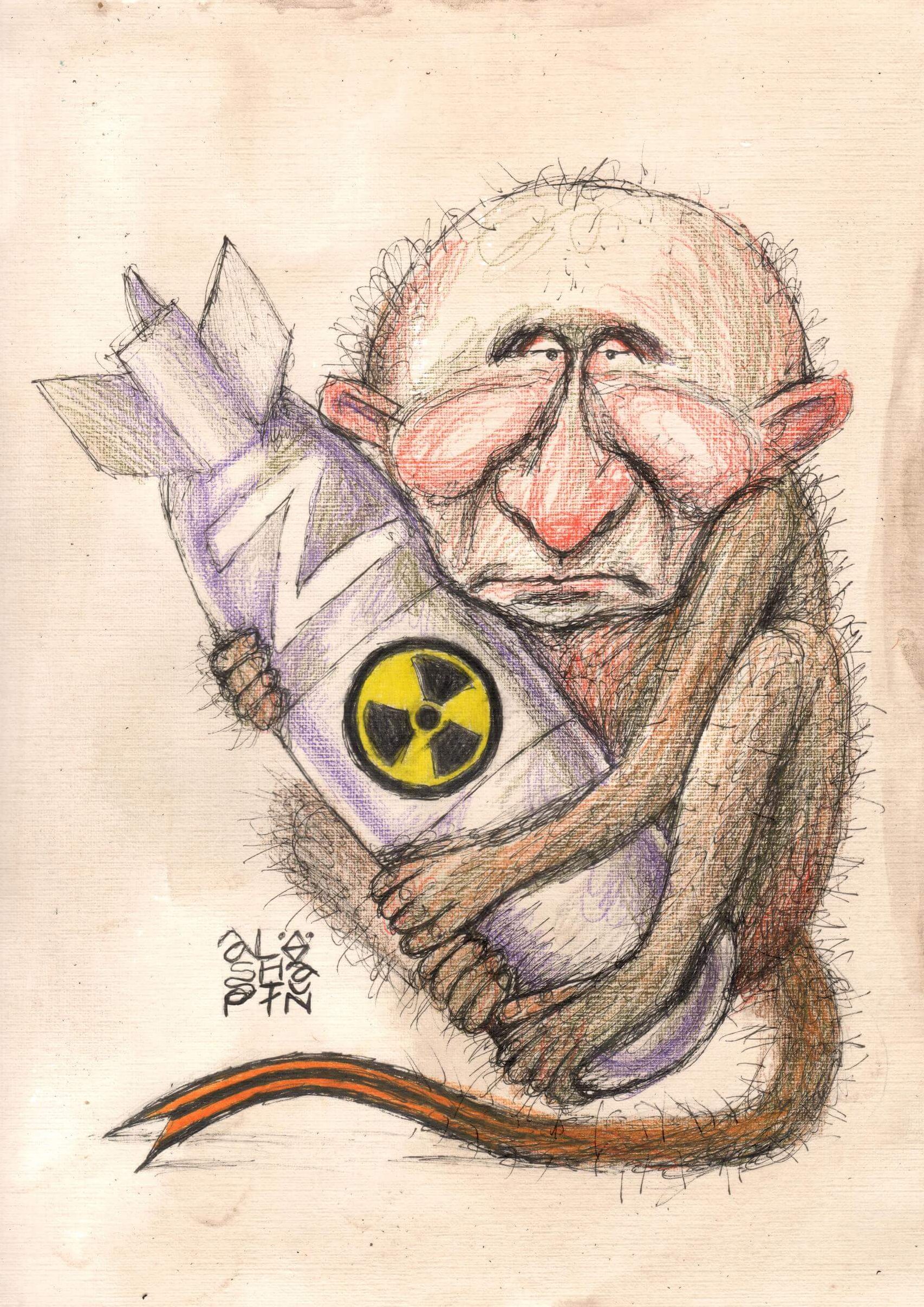

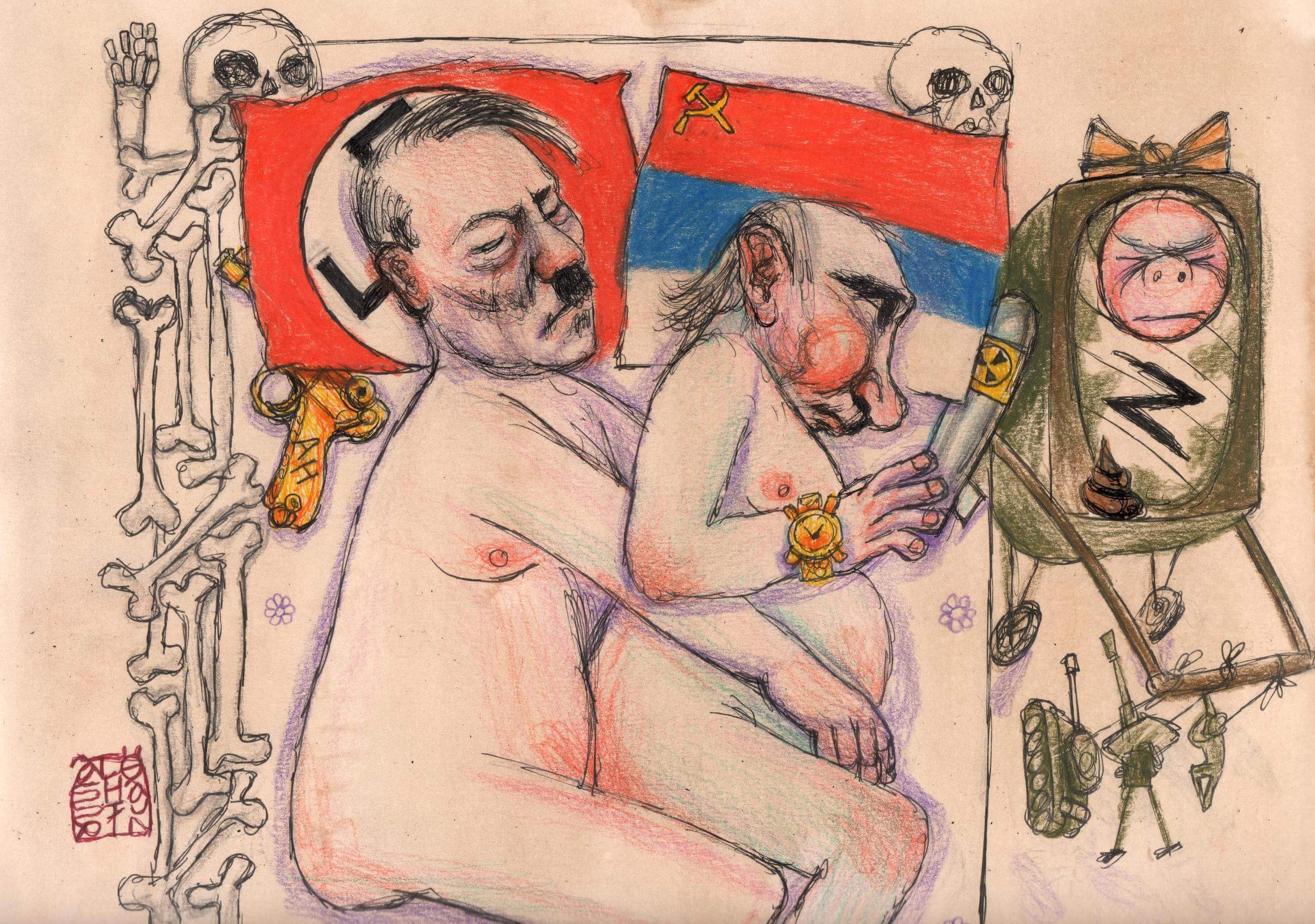

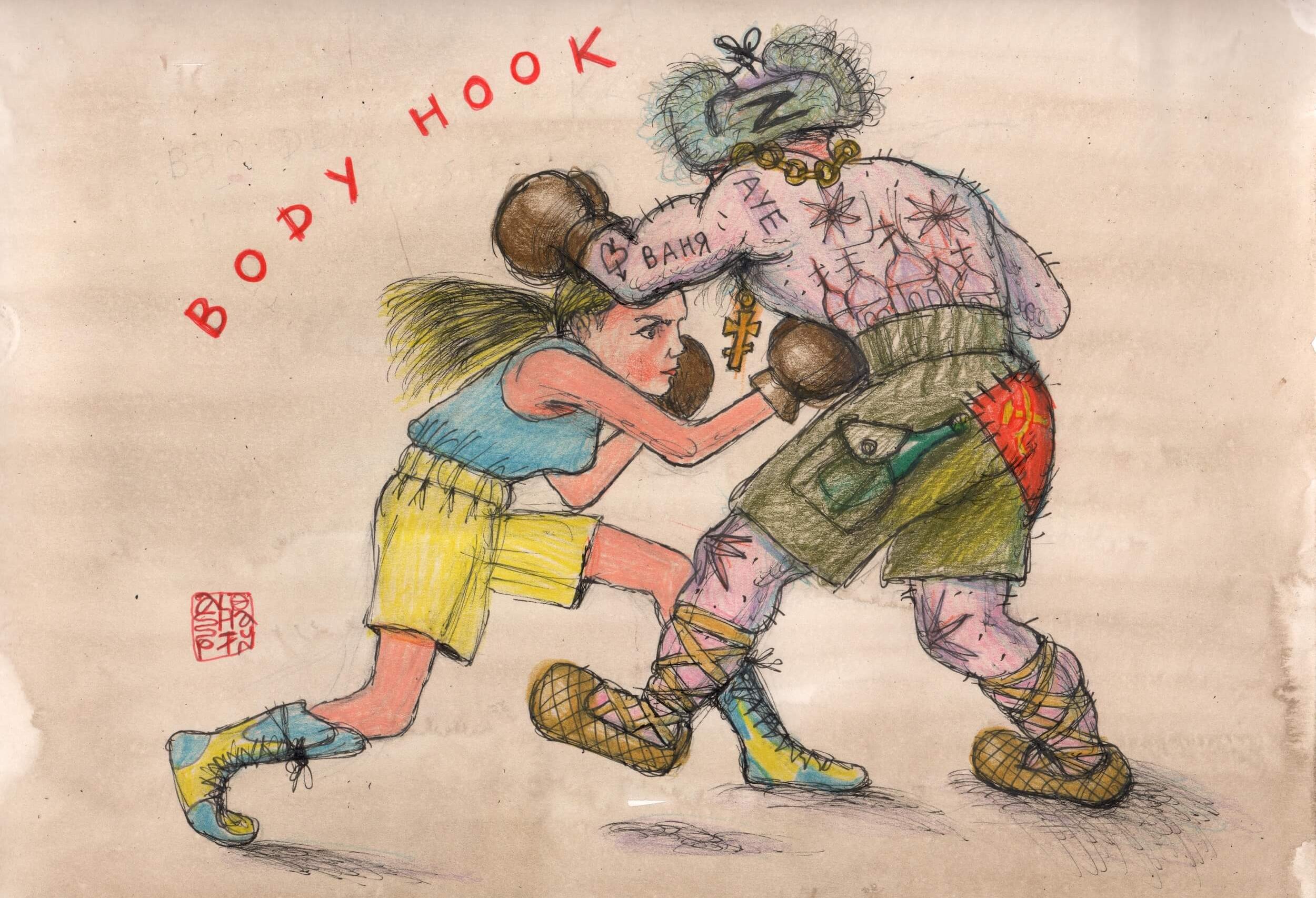

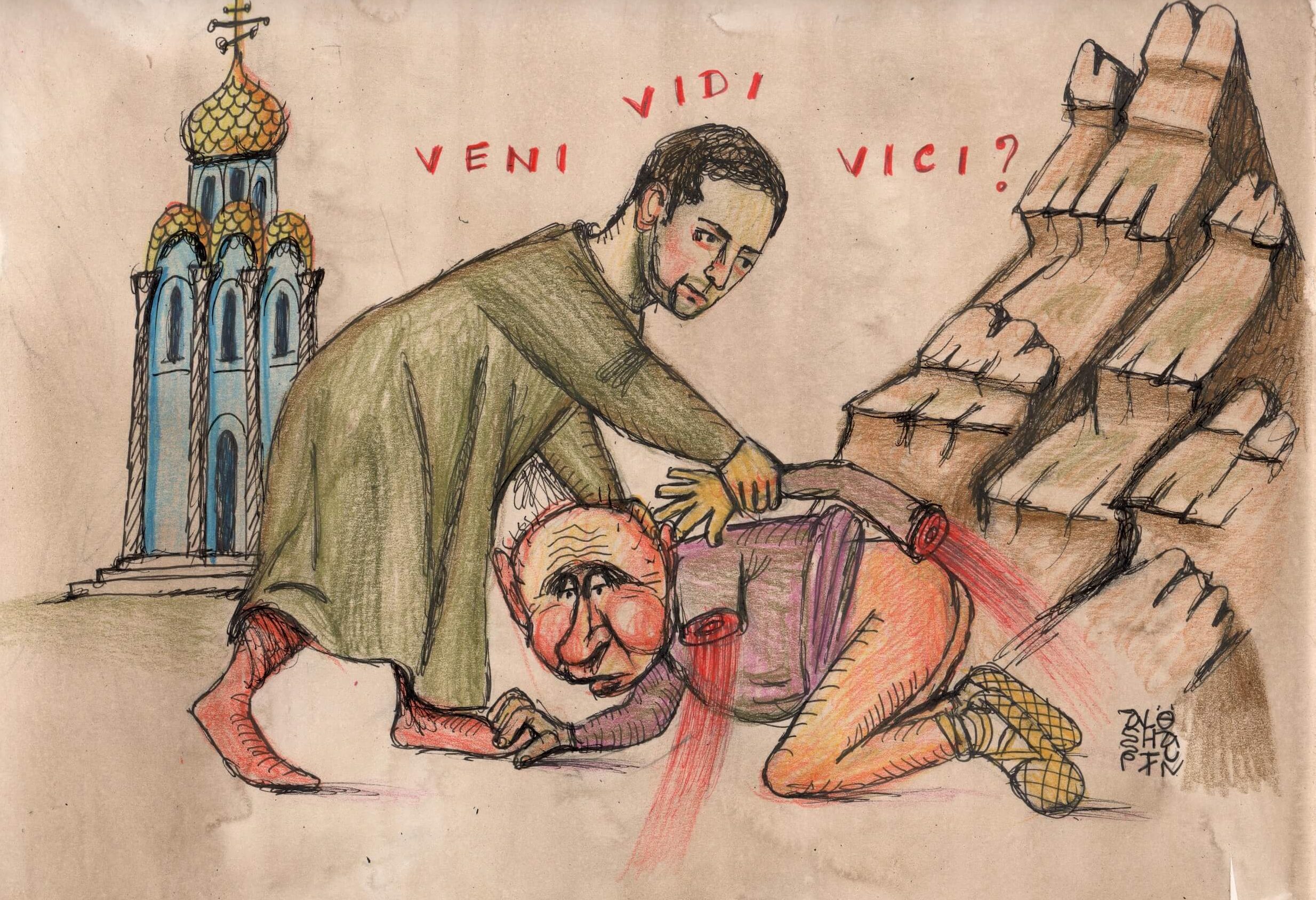

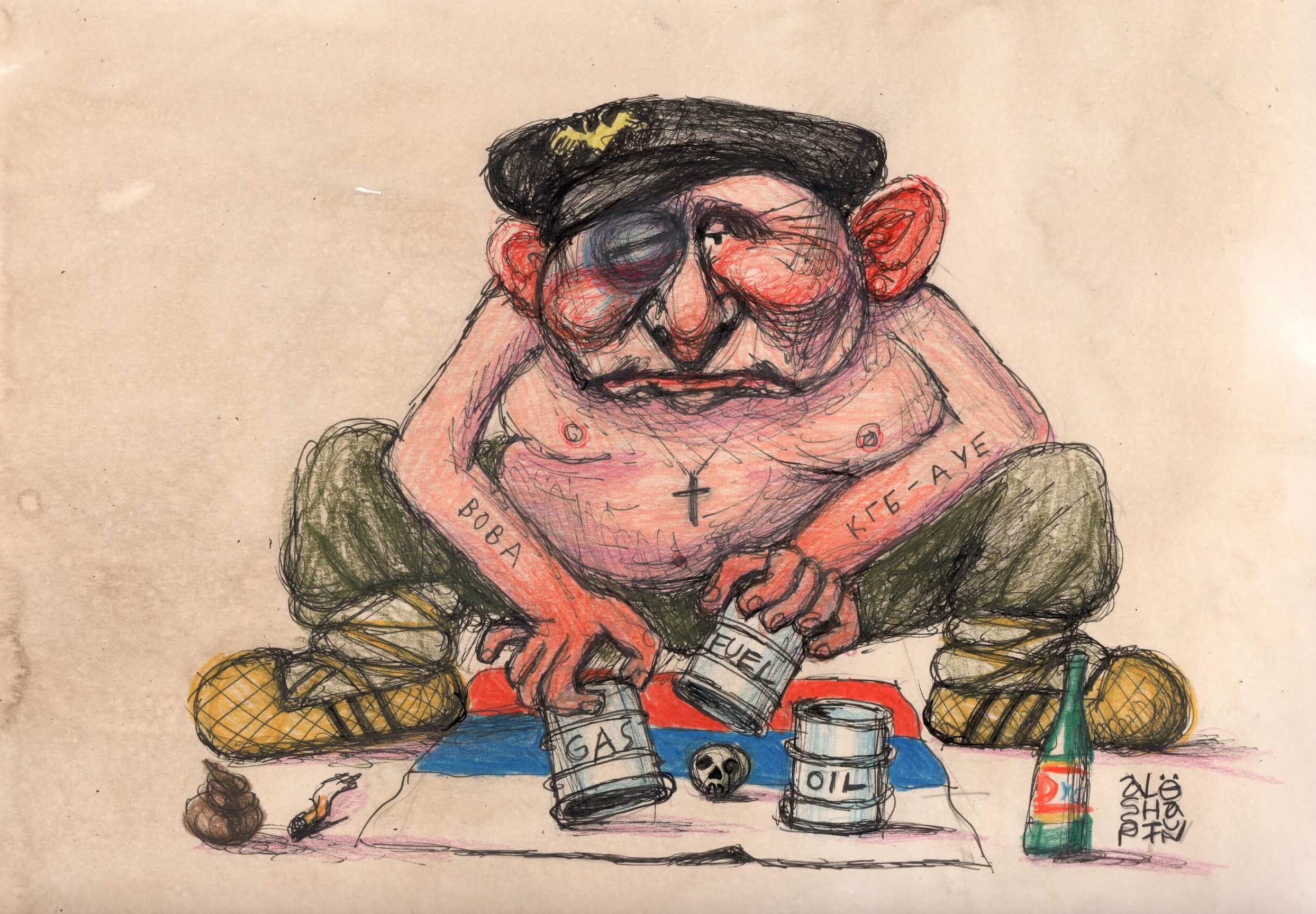

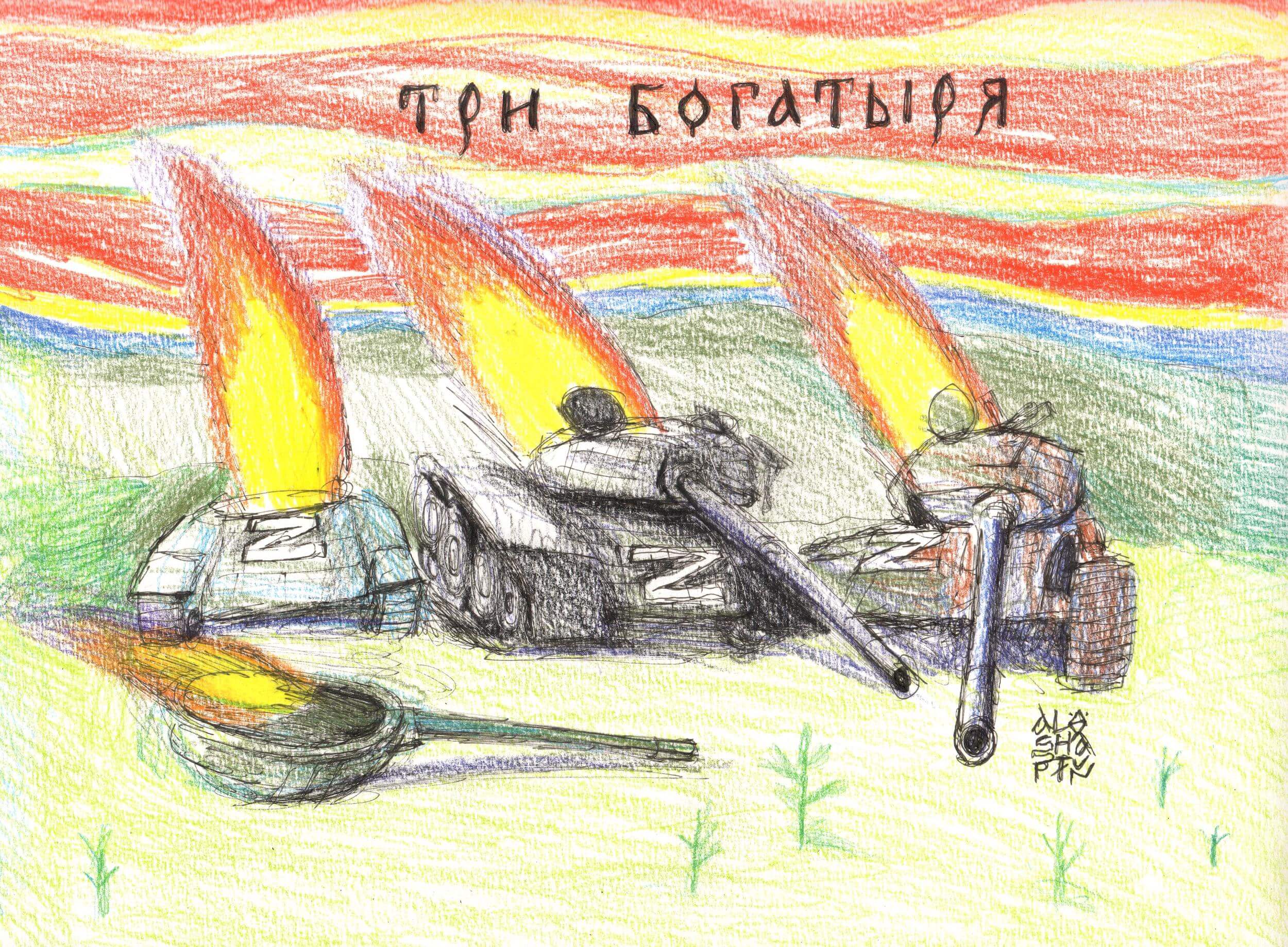

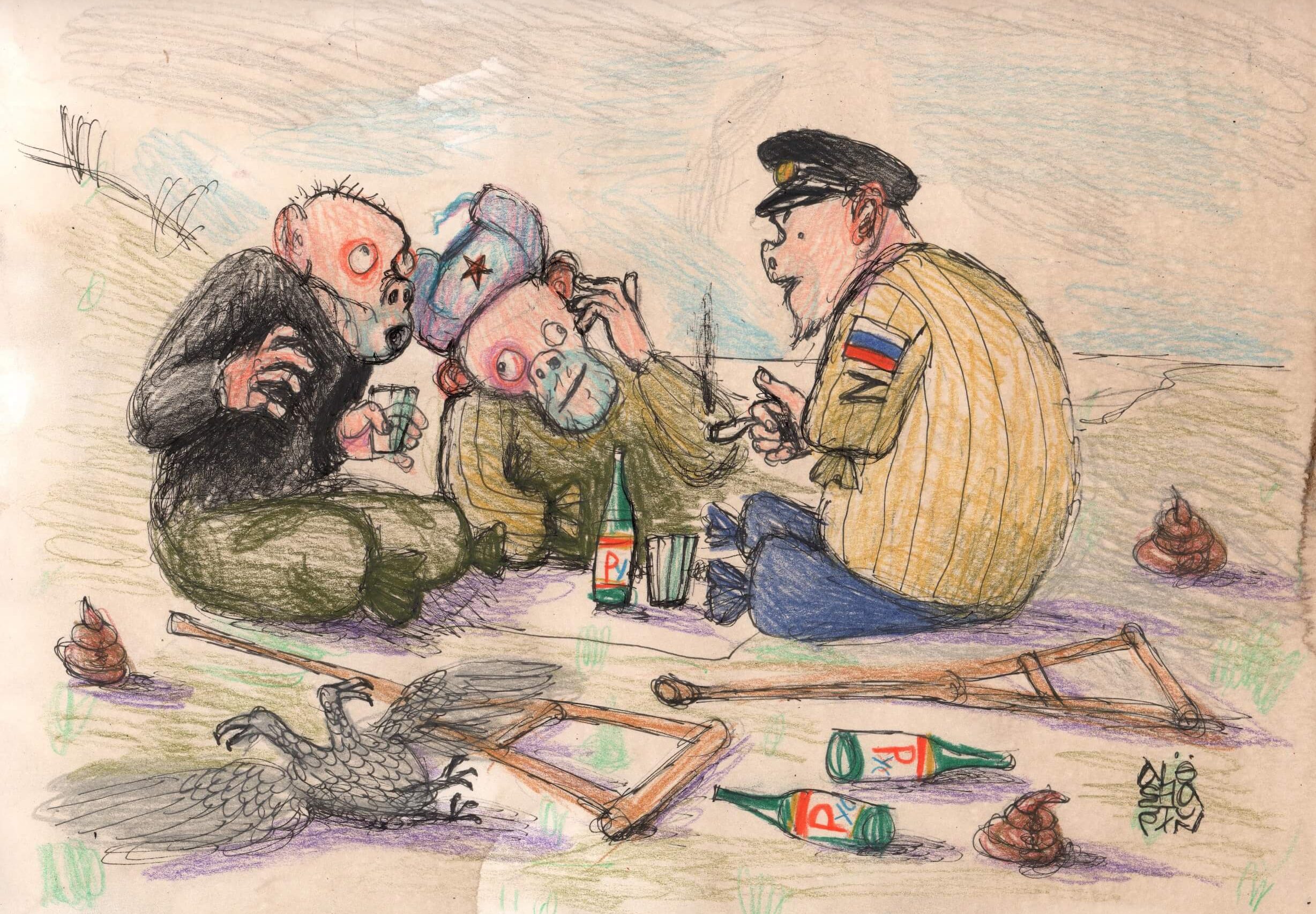

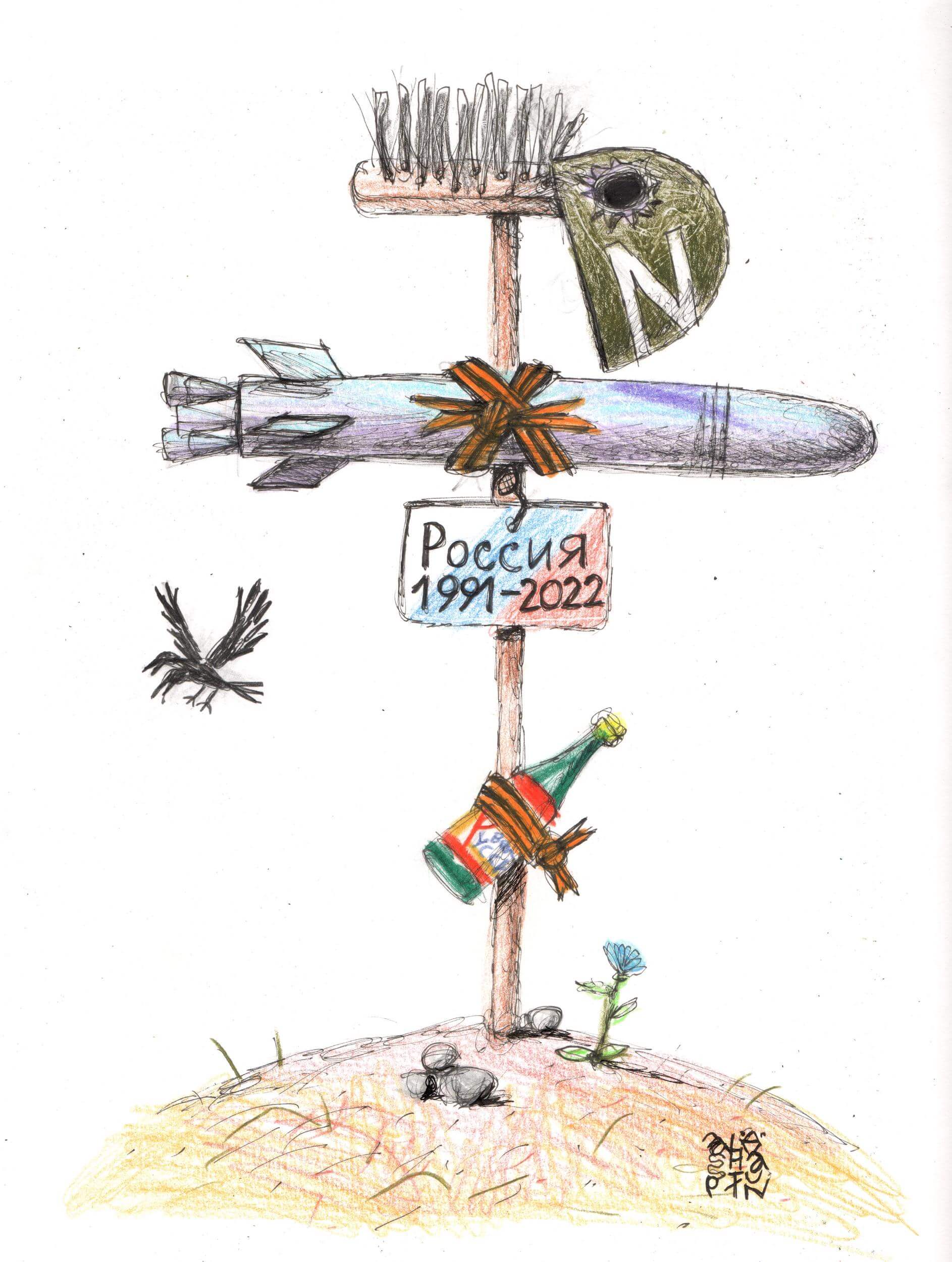

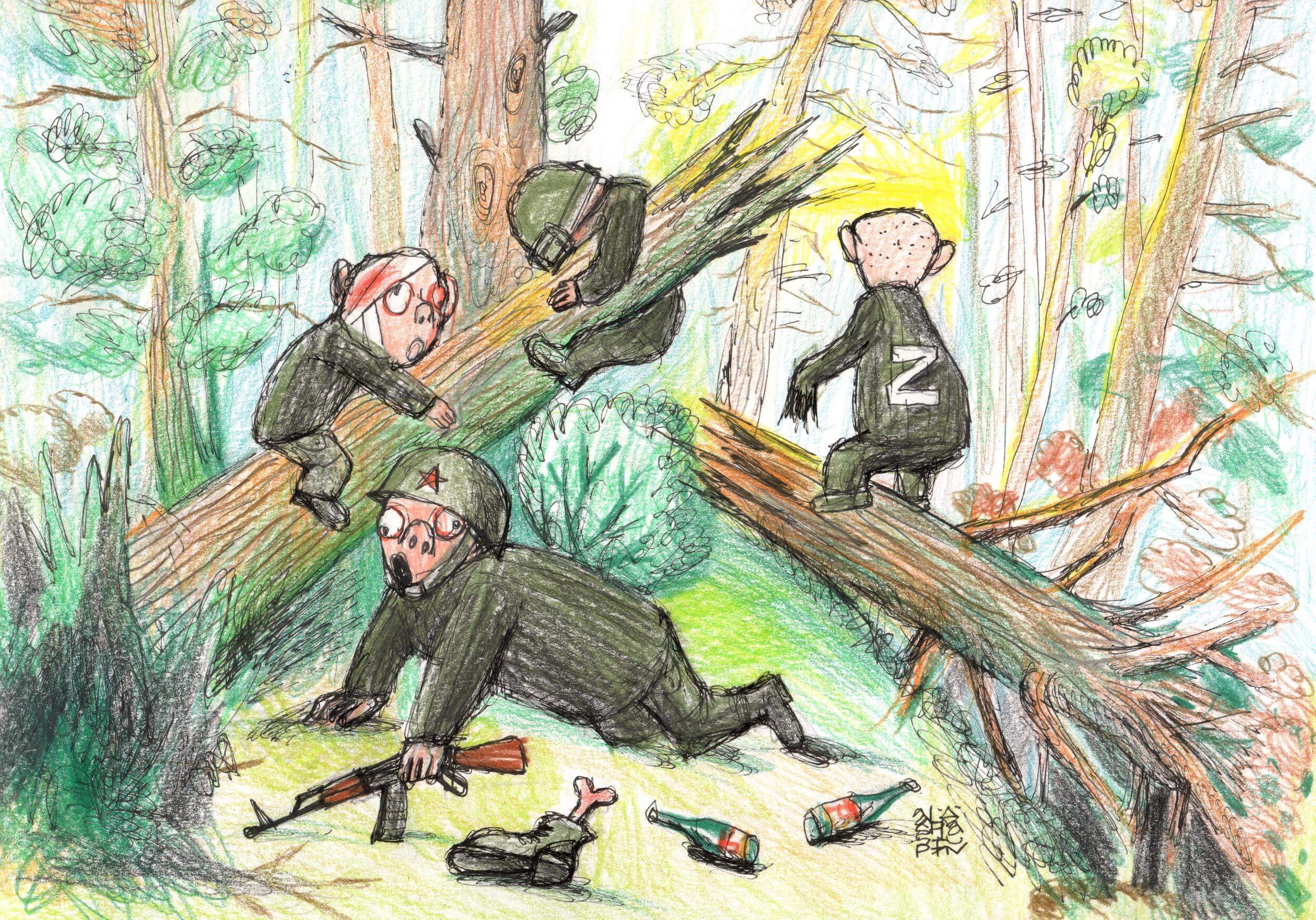

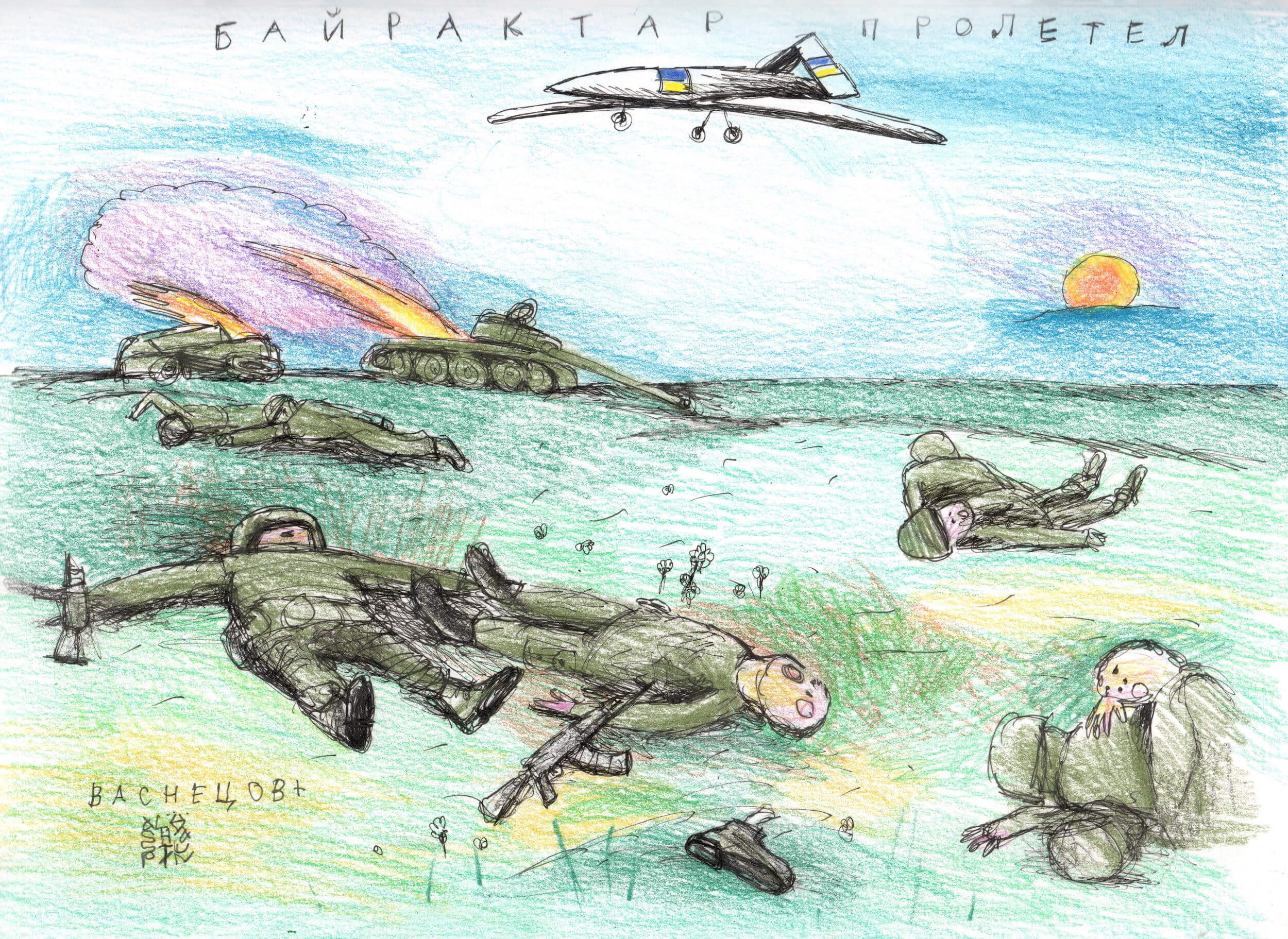

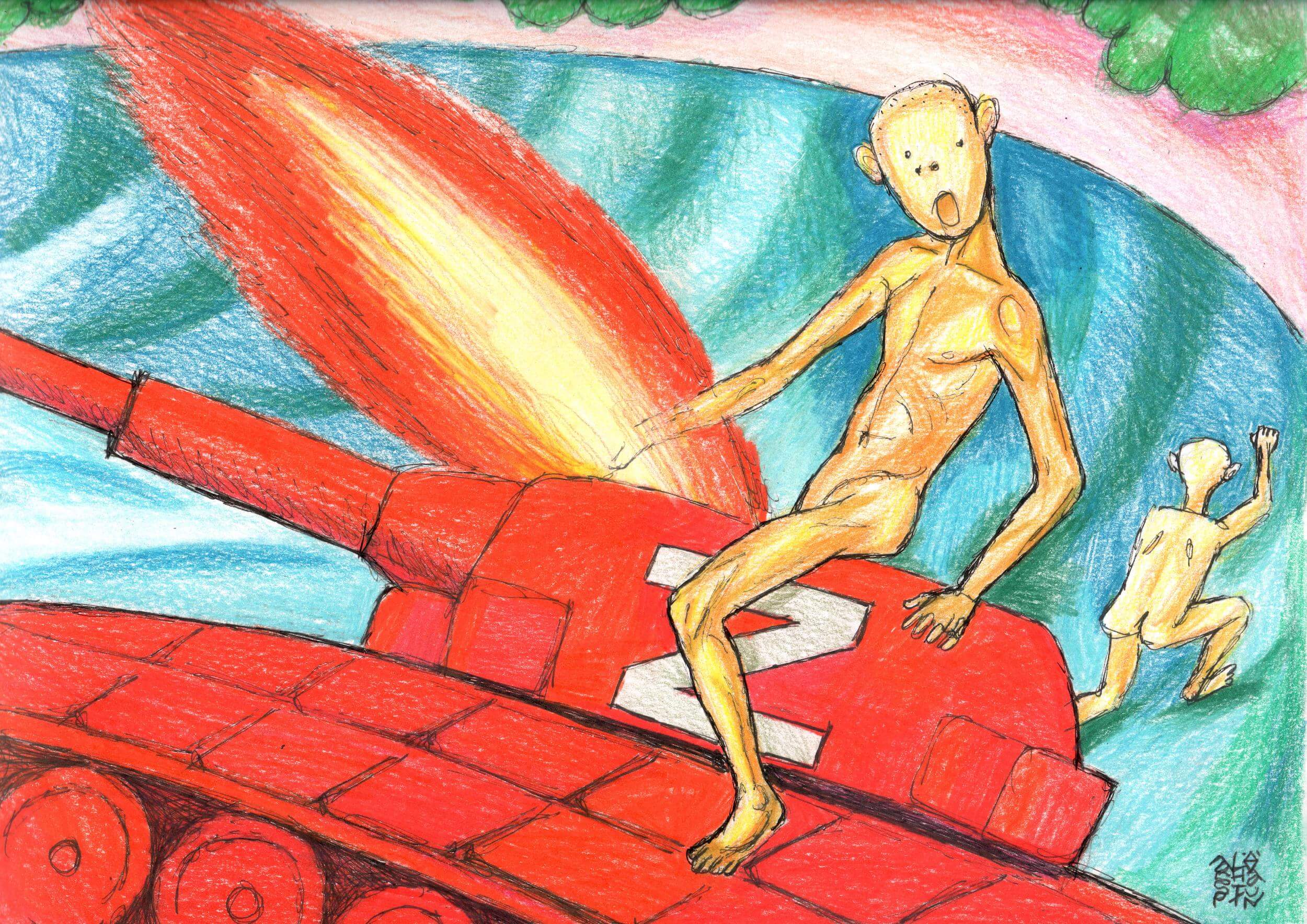

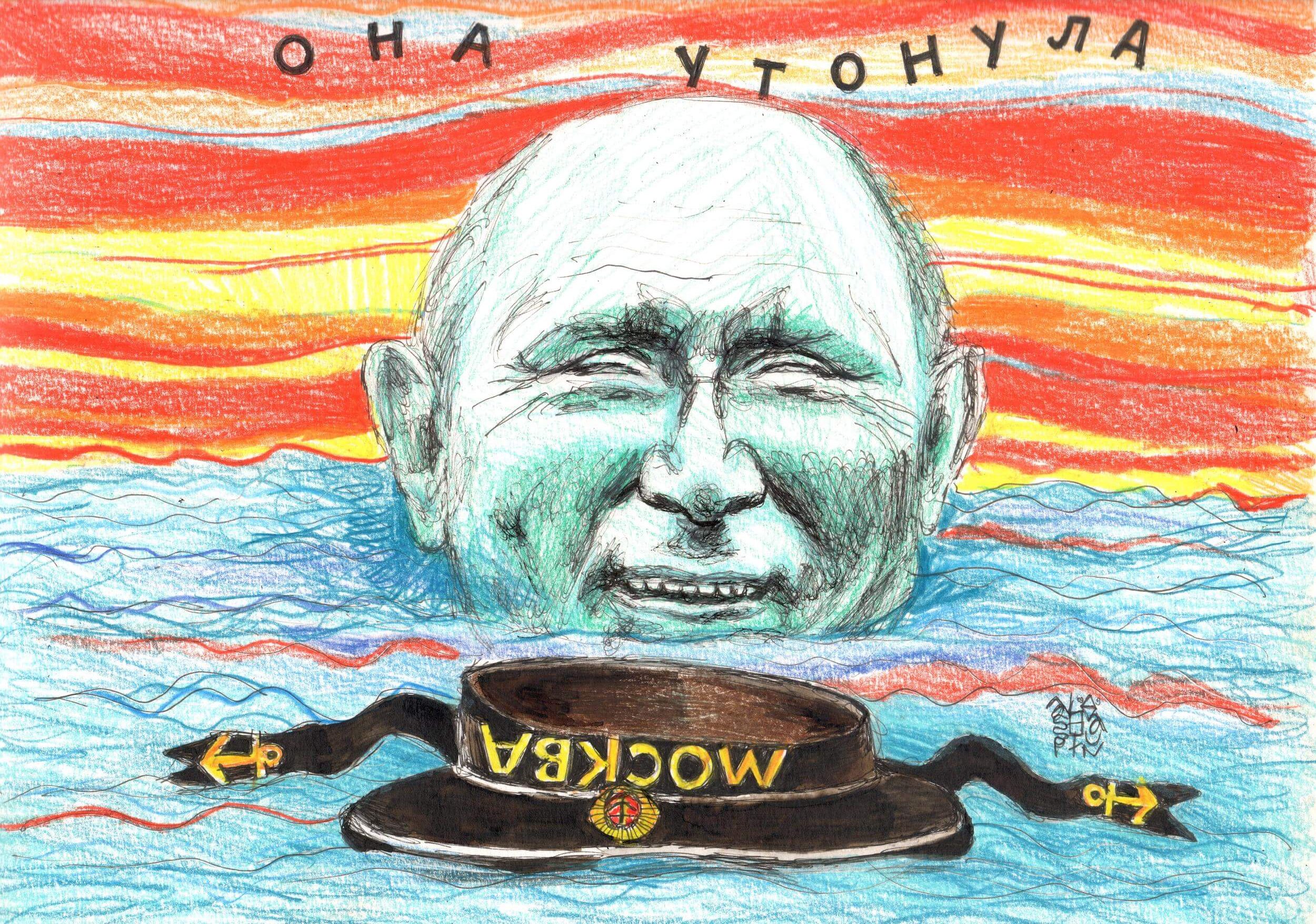

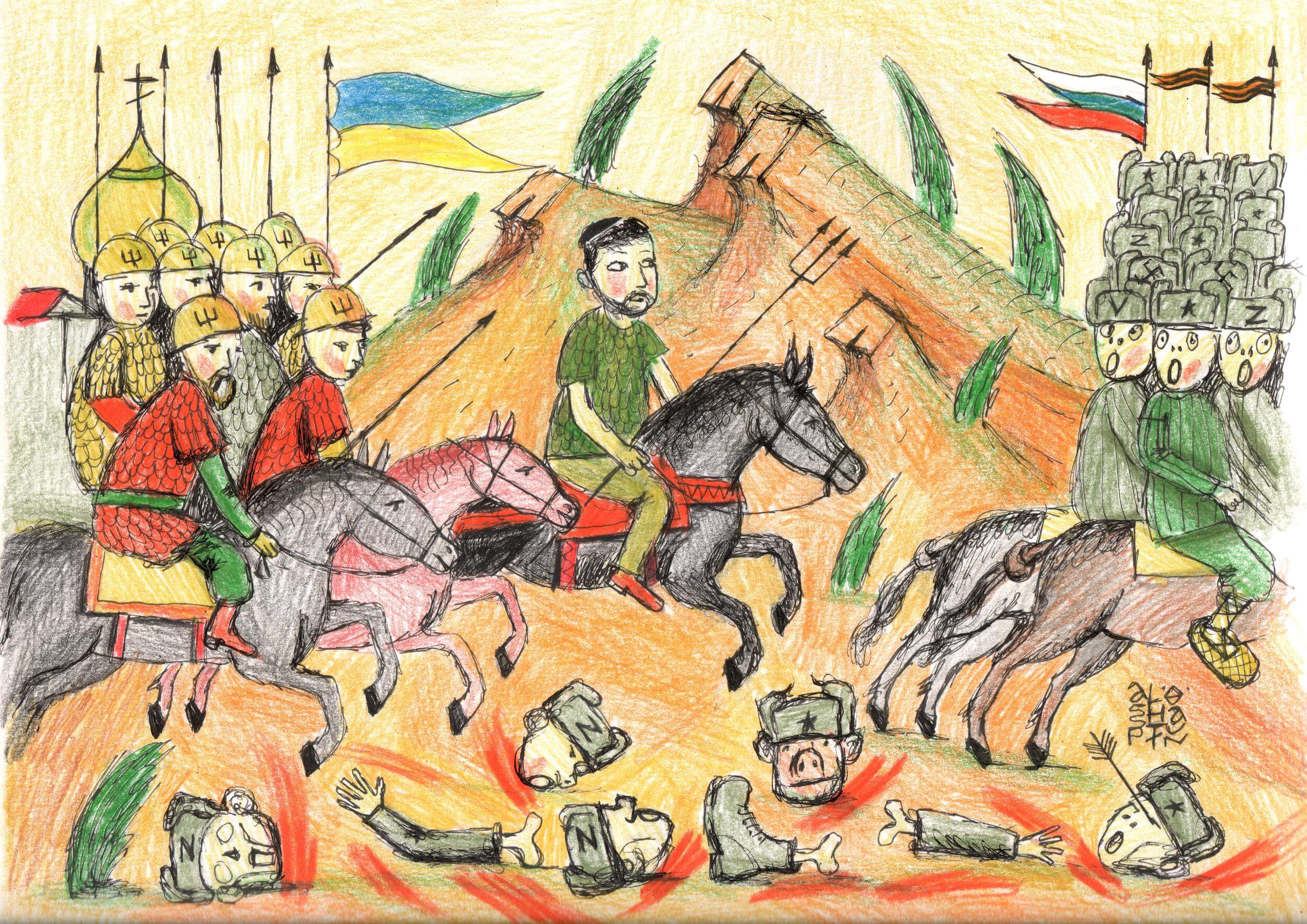

The Russian World Through the Eyes of a Child: Igor Ponochevny’s Caricatures

Since February 24, Ponochevny has been sketching caricatures every day. These drawings are ridiculing the jingoistic frenzy of his fellow countrypeople in the war against Ukraine. The regular heroes of his works are Russia’s president and Russian soldiers, who unexpectedly find themselves inside various art masterpieces. The artist spoke with Bird in Flight about his life as a pro-Ukraine Russian in the US.

Russian artist and writer. Graduated from Valentin Serov Art College of Leningrad in the eighties and went on to study law and work in banks. In 2015, moved from Saint Petersburg to the US. Lives and works in San Francisco.

— My love for caricature does not come naturally: I started practicing it after the annexation of Crimea and the east of Ukraine. I wanted to mock my compatriots. I quit my job right away and decided to leave Russia because my views were different from the majority’s. I was certain a large-scale war was bound to happen. It did. In 2015, I emigrated to the US because the atmosphere in Russia was psychologically difficult and dangerous for art and self-expression. I wrote a collection of humorous short stories, which, incidentally, was published by the Ukrainian house Folio and is available in Ukraine. And in 2016, a book with my sketches, “Vatnik’s ABC.” (Translator’s note: “vatnik” is a political slur used to denote a steadfast follower of propaganda from the Russian government — Translator’s note)

I came up with my pseudonym, Alyosha Stupin, on the day following the annexation of Crimea, when I sketched my first caricature ridiculing the all-national euphoria around the occupation of a foreign territory. The pseudonym was a means of hiding my name because it was dangerous to sketch pungent caricatures of the authorities. A lot of people believed it was actually a kid drawing those. But I started speaking about who was really behind this pseudonym. And when the style of the sketches changed too, everyone knew it was the doing of a professional adult artist.

I emigrated to the US because the atmosphere in Russia was psychologically difficult and dangerous for art and self-expression.

The war affected me strongly, just like it did any normal person who supports Ukraine. During the first weeks, we couldn’t sleep. My wife was crying every night. She’s from Belarus, and she is a refugee too. I don’t think one has to hold a Ukrainian citizenship to care about the country stricken by the war. I was in rage at the world for letting the situation escalate. In 2018, I just couldn’t fathom how Russia was even allowed to host the FIFA World Cup. I was indignant, I protested against it, but no one cared. Everyone was sure that Putin would not attack. But everything pointed to the war.

Since the first days of the war, I started sketching to support the Ukrainians and to show the Russians how terrifying it all looked. I hardly ever speak to my ex friends from there. Very few people share my beliefs. Those who do managed to leave Russia or are leaving it now. I could go back there only after the fall of this regime.

I live in California, and since caricatures are not a source of income, I am up for any hard work. My sketches are exhibited in Europe, and I had a couple of shows in the US as well. But it takes a lot of time, and I am not very interested in negotiating all that. It’s a lot easier for me to share them with the world online, via social media: no gallery would be able to handle that much. Besides, it only takes a couple of minutes, while a gallery requires months of preparation.

My technique is simple: I use pencils, ink, including walnut ink, color pencils, and felt-tip pens. I sketch a lot because I feel guilty for Russia, so I want to be as active as possible when it comes to information warfare. I also realize that Ukraine’s victory will lead to the obliteration of Putin and Lukashenko for good measure and free Russia of all those vermin.

I sketch a lot because I feel guilty for Russia.

The Russians’ trust in the tenets of Putinism is a herd instinct. They all go whenever their government tells them. The modern-day Russia is an old cart tumbling downhill that was pushed by Putin. It’s easier for ordinary folks to jump onto this cart and see where it takes them. It’s harder to try to stop it because then you would risk your arms and legs. Only a few understand that this cart is going to fall into an abyss. I think many feel this kind of eschatological panache: “come what may, I’m gonna go out with a bang.” It’s because they are out of solutions and see it as their only resort.

I got to live in the USSR and witness its dissolution. Most of the citizens, who used to go on demonstrations, who were members of the Communist party and the Young Communist League, who believed in this ideology and the happy communist future around the corner, they just suddenly refused it all. It was basically overnight and none of those people felt any discomfort.

I also saw how many people in the USSR believed in God: hardly any, actually. Statistically, only 5% did. As soon as the USSR fell and going to church was in vogue, suddenly there were 95% of orthodox Christians. These data can be found in the seminal work “Old Churches, New Believers” by expert on religions Dmitri Furman. So judging the public sentiment now is a thankless task.

People need to be encouraged to believe in any ideas, as it was during industrialization in the Soviet Union and Germany. It’s nothing like that now. Putin has not a single idea to offer his society except for the wild idea of going back to the past. Only elderly people can fall for it.

Putin has not a single idea to offer his society except for the wild idea of going back to the past.

As for the term “the good Russians,” I think it’s harmful because any categorization of people is a slippery ground. Any ally in the fight against Putin and the war is valuable.

It might not a very pleasant thing to say, but I saw a lot of people other than Russians, people from the former Soviet countries, including Ukrainians, who like Putin. And not only in Russia but in the US too. Moreover, my entire family lives in Ukraine: my father is a Ukrainian from the Zhytomyr region, and my mother is a Pole who was registered as a Russian. She’s from Volodymyr-Volynskyi. Despite that, hardly any of my relatives share my views. Most Russian-speaking population in the US watch Russian TV, and it’s unfathomable to me. I stopped watching TV in 2008.

People are divided into those who support the ideas of the modern civilized world — changeability and separation of powers, the rule of law, the independent court, independent and diverse mass media, observance of democratic procedures, tolerance towards others, the fight against nepotism and bribery — and those who gravitate towards Putin’s paradigms. These are the immutability of power, the harsh suppression of the opposition, the monopoly on information, the fully controlled court, the monopoly in the economy, vicious clientelism and nepotism.

The longer I live in the USA, the more differences I notice when comparing it with the life in Russia. For ordinary people who came here from the former USSR, these differences are often completely imperceptible. They are convinced all the wonders of the Western world just fell from the sky. It’s hard for them to grasp that people should take an active part in the life of their country and that the public is an important mechanism in the gears of the country’s management. So they don’t vote, they don’t care about party platforms, they don’t play any role in their communities.

I have no doubt that the war will end in Ukraine’s victory and Russia’s military loss. These are not just fruitless hopes — this is a vector of historical development set after the 24th of February. The global community has united for this. Russia will be paying contributions and restoring the destroyed infrastructure. The relations between the two countries will not improve for a long time, even though many Ukrainians live in Russia.

I have no doubt that the war will end in Ukraine’s victory and Russia’s military loss. These are not just fruitless hopes — this is a vector of historical development.

I see the great political future of Ukraine as the avant-garde of Europe. My guess is, Russia will dissolve into separate states. And at some moment, none of those new states will be able to complete with Ukraine, neither in terms of territories nor economically (not to mention political aspects). That would be a blessing for both Russia and the countries sharing borders with it.

New and best